It’s been a busy year of researching, collecting, archiving and publicly screening silent cartoons here at Stathes headquarters. New projects are in the works as well, and they have kept some close friends and me truly busy over the past few weeks. One of those projects is what I hope to be the first of many boutique releases from my early animation archives: Cartoon Roots, a Blu-Ray/DVD combo of silent cartoons and a couple early sound rarities! (Ever see a Romer Grey cartoon?) I’ll report more on this exciting news here at Cartoon Research another day… first things first, let’s talk television!

As all of you Cartoon Researchers now know, this coming Monday, October 6th, your televisions will boast what I would like to call the animation broadcast event of the year. Turner Classic Movies is showing hours of rare and early cartoon programming featuring some of the first animation — and some of the best! — from the early years of the art form and the industry. I’m co-hosting TCM’s Bray Studios retrospective along with Robert Osborne, which in itself is a surreal thought (pinch me!), and I am extremely proud to have provided TCM with the films for this broadcast.

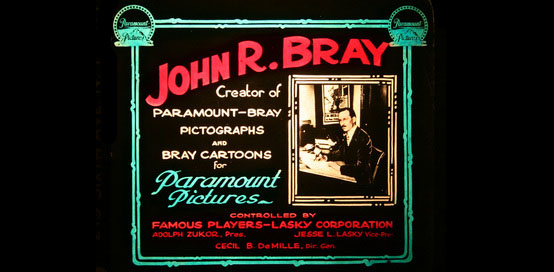

Speaking of animation as an industry, it can only be called an industry thanks to the sequence of events brought forth by John Randolph Bray and the Bray Studios a century ago. When J. Stuart Blackton, Émile Cohl and Winsor McCay breathed life into a new and mysterious filmmaking method, utilizing stop-motion puppets and drawings that seemed to move, audiences were indeed fascinated. But the new art form was seen infrequently at first, because animated cartoons were simply too difficult to make on a regular basis. The process existed, but was barely perfected or ‘practical’ by the early 1910s.

J.R. Bray and the Bray Studios changed the game: via new processes developed in-house (and some, as the story goes, unscrupulously “borrowed” from others), Bray transformed animation and created an industry. His studio, like none before it, was able to produce cartoons inexpensively and on a relatively regular schedule. There’s a lot to find out about the Bray Studios, and if you’re looking to learn more about them, I highly recommend visiting the Bray Animation Project, my online resource detailing the studio’s history and the animated films it produced.

J.R. Bray and the Bray Studios changed the game: via new processes developed in-house (and some, as the story goes, unscrupulously “borrowed” from others), Bray transformed animation and created an industry. His studio, like none before it, was able to produce cartoons inexpensively and on a relatively regular schedule. There’s a lot to find out about the Bray Studios, and if you’re looking to learn more about them, I highly recommend visiting the Bray Animation Project, my online resource detailing the studio’s history and the animated films it produced.

As a follow-up to TCM’s 2012 Early New York Animation program – provided by myself and co-hosted by our very own Jerry Beck – I decided that my next project with the channel would pay homage to this extremely significant studio, and 2014 happened to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the Bray Studio’s formal incorporation. This sort of specialty animation history programming almost never appears on broadcast TV; so I am extremely grateful to Turner Classic Movies for utilizing my archives—and most importantly, for giving TCM’s audience the opportunity to see these significant films. I’m also greatly indebted to my colleagues on the project, David Gerstein and Steve Stanchfield; without their research skills, graphic design and technical expertise, the brand new HD restoration and presentation of these rare and pivotal films would not have been possible. And now, some words about the specific films themselves…

Plot synopses written by David Gerstein, with further notes by yours truly.

THE ARTIST’S DREAM (1913) Dir. J.R. Bray. The first cartoon from pioneer producer J. R. Bray. An animated dachshund fools his live-action creator by eating the sausages he has drawn. Until, after swallowing one too many… (bad choice!). How did Bray’s cartoon career begin? In the early 1910s, like many others, he was inspired by early animation efforts from his cartooning and filmmaking peers: most notably a stop-motion film called The “Teddy” Bears (1907) and then Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo (1911). Inspired by these viewings, Bray experimented with trying to make an animated cartoon featuring his own Teddy Bear comic strip characters, but was unsuccessful. The Artist’s Dream was Bray’s second try at animation, and it worked… really well! Utilizing identical backgrounds printed on hundreds of sheets of rice paper, Bray drew in the various poses of a dachshund protagonist—Bray’s favorite dog breed, and a regular in his newspaper strips of the period. The result is a very clever, emotive, and funny turn of animated events. In case you have not already seen The Artist’s Dream, I won’t describe the climax here, but it’s one that still causes audiences and animation history students to erupt in shock and laughter over a century later. We’re incredibly lucky to have this film; part of it appears to be lost today, and the remaining segments—which play out well and still allow the film as a whole to make sense—were thankfully preserved on safety film stock by the studio before the nitrate original had completely deteriorated.

THE ARTIST’S DREAM (1913) Dir. J.R. Bray. The first cartoon from pioneer producer J. R. Bray. An animated dachshund fools his live-action creator by eating the sausages he has drawn. Until, after swallowing one too many… (bad choice!). How did Bray’s cartoon career begin? In the early 1910s, like many others, he was inspired by early animation efforts from his cartooning and filmmaking peers: most notably a stop-motion film called The “Teddy” Bears (1907) and then Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo (1911). Inspired by these viewings, Bray experimented with trying to make an animated cartoon featuring his own Teddy Bear comic strip characters, but was unsuccessful. The Artist’s Dream was Bray’s second try at animation, and it worked… really well! Utilizing identical backgrounds printed on hundreds of sheets of rice paper, Bray drew in the various poses of a dachshund protagonist—Bray’s favorite dog breed, and a regular in his newspaper strips of the period. The result is a very clever, emotive, and funny turn of animated events. In case you have not already seen The Artist’s Dream, I won’t describe the climax here, but it’s one that still causes audiences and animation history students to erupt in shock and laughter over a century later. We’re incredibly lucky to have this film; part of it appears to be lost today, and the remaining segments—which play out well and still allow the film as a whole to make sense—were thankfully preserved on safety film stock by the studio before the nitrate original had completely deteriorated.

FARMER ALFALFA SEES NEW YORK (1916) Dir. Paul Terry. Farmer Al has a rough time when big city con artists take him for a ride. But while the crooks think Al’s travel bag is full of money, it really contains his very helpful dog. Ask baby boomers born in the 1940s to name a cartoon series they saw on early television as kids, and many will answer Farmer Alfalfa. Farmer Al starred—and sometimes guest-starred—in hundreds of Paul Terry’s cartoons from the 1910s and into the 1940s, finally achieving one last hurrah of fame when 1950s TV liberally reran his 1920s Aesop’s Fables and 1930s Terrytoons appearances. Terry created Farmer Al, then unnamed, for Down On the Phoney Farm (1915)—a one-off short for Thanhouser—then revived him for his directorial debut at Bray Studios in 1916. According to some accounts, Terry’s stay at Bray took place under duress; Bray’s wife, Margaret, had seen the burgeoning animator’s work elsewhere, noticed that Terry was using cels, and gave him the choice of working at Bray Studios—or being sued by Bray for using animation techniques protected by the Bray-Hurd Patents company. Terry directed eleven Farmer Alfalfa cartoons for Bray in 1916; then went on to become one of the main cartoon studio heads of animation’s Golden Age, eventually achieving fame for Mighty Mouse and Heckle and Jeckle. Farmer Alfalfa Sees New York was preserved as a near-complete 16mm home use print sold from the 1930s to the 1950s; missing footage has been reinserted from a deteriorating original 35mm nitrate print, recently preserved in the nick of time by the Library of Congress.

FARMER ALFALFA SEES NEW YORK (1916) Dir. Paul Terry. Farmer Al has a rough time when big city con artists take him for a ride. But while the crooks think Al’s travel bag is full of money, it really contains his very helpful dog. Ask baby boomers born in the 1940s to name a cartoon series they saw on early television as kids, and many will answer Farmer Alfalfa. Farmer Al starred—and sometimes guest-starred—in hundreds of Paul Terry’s cartoons from the 1910s and into the 1940s, finally achieving one last hurrah of fame when 1950s TV liberally reran his 1920s Aesop’s Fables and 1930s Terrytoons appearances. Terry created Farmer Al, then unnamed, for Down On the Phoney Farm (1915)—a one-off short for Thanhouser—then revived him for his directorial debut at Bray Studios in 1916. According to some accounts, Terry’s stay at Bray took place under duress; Bray’s wife, Margaret, had seen the burgeoning animator’s work elsewhere, noticed that Terry was using cels, and gave him the choice of working at Bray Studios—or being sued by Bray for using animation techniques protected by the Bray-Hurd Patents company. Terry directed eleven Farmer Alfalfa cartoons for Bray in 1916; then went on to become one of the main cartoon studio heads of animation’s Golden Age, eventually achieving fame for Mighty Mouse and Heckle and Jeckle. Farmer Alfalfa Sees New York was preserved as a near-complete 16mm home use print sold from the 1930s to the 1950s; missing footage has been reinserted from a deteriorating original 35mm nitrate print, recently preserved in the nick of time by the Library of Congress.

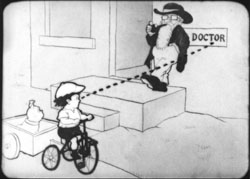

BOBBY BUMPS’ DOG GETS THE FLEA-ENZA (1919). Dir. Earl Hurd. Bobby thinks he’s got Fido protected from the flu, but Fido’s cat rival is out to make sure he gets sick. Bobby Bumps is perhaps the most historically significant series star to have graced Bray Studios’ production output. While Bray had the distinction of creating Col. Heeza Liar, the first recurring animated cartoon character and the first character created specifically for the screen, it was Earl Hurd’s use of cels, and the subsequent Bray-Hurd Process, that truly ushered in quicker and more efficient animation at the studio and throughout the industry. Other studios either paid Bray-Hurd a royalty for the use of cels; used them illicitly and wound up in court; or continued to rely on older, more awkward techniques. Hurd’s Bobby Bumps series, while not fluidly animated, features clever storylines, amusing gags and facial expressions, and entertaining puns. Born as “Brick Bodkins” — a Hurd newspaper strip character dating back to 1912 — Bobby Bumps was an endearing and mischievous little boy who set the course of animation’s dependence on cels for decades to follow.

BOBBY BUMPS’ DOG GETS THE FLEA-ENZA (1919). Dir. Earl Hurd. Bobby thinks he’s got Fido protected from the flu, but Fido’s cat rival is out to make sure he gets sick. Bobby Bumps is perhaps the most historically significant series star to have graced Bray Studios’ production output. While Bray had the distinction of creating Col. Heeza Liar, the first recurring animated cartoon character and the first character created specifically for the screen, it was Earl Hurd’s use of cels, and the subsequent Bray-Hurd Process, that truly ushered in quicker and more efficient animation at the studio and throughout the industry. Other studios either paid Bray-Hurd a royalty for the use of cels; used them illicitly and wound up in court; or continued to rely on older, more awkward techniques. Hurd’s Bobby Bumps series, while not fluidly animated, features clever storylines, amusing gags and facial expressions, and entertaining puns. Born as “Brick Bodkins” — a Hurd newspaper strip character dating back to 1912 — Bobby Bumps was an endearing and mischievous little boy who set the course of animation’s dependence on cels for decades to follow.

HOW ANIMATED CARTOONS ARE MADE (1919). Dir. Wallace Carlson. A documentary shows how it was done at Bray Studios, with help from director Wallace Carlson and his “Us Fellers” characters Dreamy Dud and Mamie. This is a fascinating and rare film that was not released as a cartoon—but as an educational portions of the “Magazine” reels (weekly compilations of cartoons, educational shorts, novelties, etc.) that Bray was producing at the time. Going by period reviews and letters to magazine editors of the time, it’s obvious that by the late 1910s, many average men, women and children thoroughly enjoyed cartoons and wanted to know how they were made, so this was Bray’s answer. What’s interesting about this film is that the true animation techniques employed at the studio are never actually shown or discussed. The viewer is only given a rudimentary explanation of drawing sequences and cycles; one learns nothing about the use of cels and other necessary techniques. I think the reason for this is obvious: Bray, the unforgiving animation-cel patent king who spent years in court suing rivals for infringement, would not want the average movie-goer to know how to make an animated cartoon. This restoration of the film comes from a nearly century-old 28mm film print discovered in a midwestern barn a couple of years ago.

HOW ANIMATED CARTOONS ARE MADE (1919). Dir. Wallace Carlson. A documentary shows how it was done at Bray Studios, with help from director Wallace Carlson and his “Us Fellers” characters Dreamy Dud and Mamie. This is a fascinating and rare film that was not released as a cartoon—but as an educational portions of the “Magazine” reels (weekly compilations of cartoons, educational shorts, novelties, etc.) that Bray was producing at the time. Going by period reviews and letters to magazine editors of the time, it’s obvious that by the late 1910s, many average men, women and children thoroughly enjoyed cartoons and wanted to know how they were made, so this was Bray’s answer. What’s interesting about this film is that the true animation techniques employed at the studio are never actually shown or discussed. The viewer is only given a rudimentary explanation of drawing sequences and cycles; one learns nothing about the use of cels and other necessary techniques. I think the reason for this is obvious: Bray, the unforgiving animation-cel patent king who spent years in court suing rivals for infringement, would not want the average movie-goer to know how to make an animated cartoon. This restoration of the film comes from a nearly century-old 28mm film print discovered in a midwestern barn a couple of years ago.

THE TALE OF A WAG (1920). When railroad boss Mr. Givney needs a pesky mosquito exterminated, Jerry is on the job. But Jerry’s efforts bug Givney more than the bug. Walt Hoban’s famous Jerry on the Job comic strip was one of many newspaper features to be animated for the silent screen. The Jerry titles were some of the shorter cartoons released by Bray, mostly clocking in at four minutes or less in length. Jerry, his dog and boss Mr. Givney seem to always be stuck at New Monia, the train station they manage. The trio of characters, while limited by their surroundings, go through some fun and bizarre scenarios beside the rails, and the animators who worked on this series—such as Vernon Stallings, a very young Walter Lantz, and others—typically peppered the films with some very fun gags. Many films in the series, such as this entry, were subsequently preserved as 16mm home use prints, enjoyed by children as late as the 1940s and 1950s.

THE TALE OF A WAG (1920). When railroad boss Mr. Givney needs a pesky mosquito exterminated, Jerry is on the job. But Jerry’s efforts bug Givney more than the bug. Walt Hoban’s famous Jerry on the Job comic strip was one of many newspaper features to be animated for the silent screen. The Jerry titles were some of the shorter cartoons released by Bray, mostly clocking in at four minutes or less in length. Jerry, his dog and boss Mr. Givney seem to always be stuck at New Monia, the train station they manage. The trio of characters, while limited by their surroundings, go through some fun and bizarre scenarios beside the rails, and the animators who worked on this series—such as Vernon Stallings, a very young Walter Lantz, and others—typically peppered the films with some very fun gags. Many films in the series, such as this entry, were subsequently preserved as 16mm home use prints, enjoyed by children as late as the 1940s and 1950s.

THE BEST MOUSE LOSES (1920). When Ignatz Mouse becomes a boxer, helpful Krazy Kat tries to rig a boxing match in his favor. But Krazy doesn’t know that Ignatz has bet on himself to lose. Krazy Kat is a veritable god(dess?) in the history of comics, and I feel there’s no real necessity for me to explain this character’s history and significance in American pop culture. Krazy Kat was simply one of several popular comic characters of the day whose likeness was translated to the cinema screen, at first for no reason other than profit. International Film Service’s animated version of the character in 1916 featured storylines especially close to Herriman’s style but the animation was clumsy, stiff, and left much to desire. By 1920, with new blood working on the series for Bray, the results came a little closer to the Herriman look; storylines were a bit more hit and miss, but Best Mouse hits the target nicely.

THE BEST MOUSE LOSES (1920). When Ignatz Mouse becomes a boxer, helpful Krazy Kat tries to rig a boxing match in his favor. But Krazy doesn’t know that Ignatz has bet on himself to lose. Krazy Kat is a veritable god(dess?) in the history of comics, and I feel there’s no real necessity for me to explain this character’s history and significance in American pop culture. Krazy Kat was simply one of several popular comic characters of the day whose likeness was translated to the cinema screen, at first for no reason other than profit. International Film Service’s animated version of the character in 1916 featured storylines especially close to Herriman’s style but the animation was clumsy, stiff, and left much to desire. By 1920, with new blood working on the series for Bray, the results came a little closer to the Herriman look; storylines were a bit more hit and miss, but Best Mouse hits the target nicely.

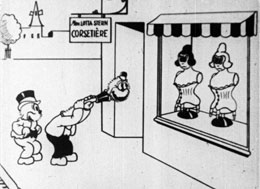

A FITTING GIFT (1920). Judge Rummy and Silk Hat Harry want to buy Rummy’s wife a corset, but can’t enter a ladies’ underwear store without raising eyebrows. The solution: disguise themselves as girls! What could possibly go wrong? Judge Rummy, another famous comic strip character of the period, proved to be one of the funniest series in Bray’s selection of newspaper-strip-to-theater-screen adaptations. Notable figures in animation history such as Grim Natwick, Burt Gillett, Jack King, and Gregory LaCava all worked on the series with extremely pleasing results. This example was thankfully preserved as a 16mm home use release, enjoyed by youngsters with toy film projectors well into the 1950s. But perhaps the Fitting Gift storyline isn’t the most appropriate for kids…

A FITTING GIFT (1920). Judge Rummy and Silk Hat Harry want to buy Rummy’s wife a corset, but can’t enter a ladies’ underwear store without raising eyebrows. The solution: disguise themselves as girls! What could possibly go wrong? Judge Rummy, another famous comic strip character of the period, proved to be one of the funniest series in Bray’s selection of newspaper-strip-to-theater-screen adaptations. Notable figures in animation history such as Grim Natwick, Burt Gillett, Jack King, and Gregory LaCava all worked on the series with extremely pleasing results. This example was thankfully preserved as a 16mm home use release, enjoyed by youngsters with toy film projectors well into the 1950s. But perhaps the Fitting Gift storyline isn’t the most appropriate for kids…

THE CIRCUS (1920). Dir. by Max and Dave Fleischer. Koko the Clown tries to train Napoleon the circus horse, but this old nag just ain’t what he used to be. In fact, he’s such a disgrace that he can’t even die – horse heaven won’t let him in. The Fleischer brothers had an immense impact on the early animation industry—and on the art form as well. Max, a great technical artist, came to know Bray during a period in the early 1900s when both worked at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Later, a chance reunion between occurred just as Max was touting a sample reel of an animated clown, utilizing the Rotoscope process he had developed for tracing live-action film to create animation. Bray subsequently hired Max to produce several technical and educational films for the Bray Studios, and it was there that Max brought the first Out of the Inkwell shorts together—rotoscoping footage of his brother (and the films’ director) Dave Fleischer prancing around in his Coney Island clown costume. At this time, the character was simply known as the Goldwyn-Bray Clown, denoting the distributor of Bray’s films from 1919 to 1921. Later, we would all come to know the clown as Koko, and the Fleischers went on to achieve historic fame with Betty Boop, Popeye, and the groundbreaking Superman cartoons.

THE CIRCUS (1920). Dir. by Max and Dave Fleischer. Koko the Clown tries to train Napoleon the circus horse, but this old nag just ain’t what he used to be. In fact, he’s such a disgrace that he can’t even die – horse heaven won’t let him in. The Fleischer brothers had an immense impact on the early animation industry—and on the art form as well. Max, a great technical artist, came to know Bray during a period in the early 1900s when both worked at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Later, a chance reunion between occurred just as Max was touting a sample reel of an animated clown, utilizing the Rotoscope process he had developed for tracing live-action film to create animation. Bray subsequently hired Max to produce several technical and educational films for the Bray Studios, and it was there that Max brought the first Out of the Inkwell shorts together—rotoscoping footage of his brother (and the films’ director) Dave Fleischer prancing around in his Coney Island clown costume. At this time, the character was simply known as the Goldwyn-Bray Clown, denoting the distributor of Bray’s films from 1919 to 1921. Later, we would all come to know the clown as Koko, and the Fleischers went on to achieve historic fame with Betty Boop, Popeye, and the groundbreaking Superman cartoons.

COL. HEEZA LIAR, DETECTIVE (1923) Dir. Vernon Stallings. Heeza Liar is sent out to bring back a stolen chicken alive. Our hero vows he’ll never fail – but the bird’s goose is already cooked. Will the thieves make a liar out of Heeza? Col. Heeza Liar was a true J.R. Bray creation, and the first character to be created specifically for animated cartoons. Heeza Liar was also the first character to appear in a recurring series. Debuting in 1913, the Colonel starred in over fifty cartoons, most based on the premise of his telling—or experiencing—windy, tall-tale-like adventures. Throughout the teens, many of the subjects were appropriately war-related. Bray put the character to rest in 1917 and decided it was time for a revival in 1922, at which point Col. Heeza Liar enjoyed a series of new adventures combining live-action and animation. Vernon Stallings and a young Walter Lantz oversaw this newer—and in my opinion, more entertaining—manifestation of Heeza Liar. The Colonel, in many ways, is the grandfather of all recurring animated cartoon characters, all of whom owe him some thanks for being the first to revisit audiences on a regular basis. In the 1930s, Col. Heeza Liar was occasionally remembered in the press as “the Mickey Mouse of his day”; an apt appellation for this iconic figure.

COL. HEEZA LIAR, DETECTIVE (1923) Dir. Vernon Stallings. Heeza Liar is sent out to bring back a stolen chicken alive. Our hero vows he’ll never fail – but the bird’s goose is already cooked. Will the thieves make a liar out of Heeza? Col. Heeza Liar was a true J.R. Bray creation, and the first character to be created specifically for animated cartoons. Heeza Liar was also the first character to appear in a recurring series. Debuting in 1913, the Colonel starred in over fifty cartoons, most based on the premise of his telling—or experiencing—windy, tall-tale-like adventures. Throughout the teens, many of the subjects were appropriately war-related. Bray put the character to rest in 1917 and decided it was time for a revival in 1922, at which point Col. Heeza Liar enjoyed a series of new adventures combining live-action and animation. Vernon Stallings and a young Walter Lantz oversaw this newer—and in my opinion, more entertaining—manifestation of Heeza Liar. The Colonel, in many ways, is the grandfather of all recurring animated cartoon characters, all of whom owe him some thanks for being the first to revisit audiences on a regular basis. In the 1930s, Col. Heeza Liar was occasionally remembered in the press as “the Mickey Mouse of his day”; an apt appellation for this iconic figure.

DINKY DOODLE LOST AND FOUND (1926). Dir. by Walter Lantz. When a thuggish – but strangely polite – kidnapper pursues a beautiful damsel, cartoon director Walter Lantz intervenes in the chase. By the early 1920s, Walter Lantz was a budding animator at Bray, with a directorial position on the horizon. Lantz had cut his teeth as a teenager working at the International Film Service cartoon studio in the late teens, whose animation production of the Hearst-owned comic characters was eventually handled by Bray. For a variety of reasons, Bray’s major players such as Earl Hurd, Max Fleischer, and others had all left the studio by 1921. Along with director Vernon Stallings, Lantz began working on Bray’s reincarnation of Col. Heeza Liar in 1923, and by 1924, Lantz took center stage at the studio with his introduction of the Dinky Doodle series. Lantz proved to be Bray’s final director of cartoons; by 1927, the studio formally withdrew from producing animation. With other studios producing more critically-acclaimed series like Felix the Cat and Inkwell Imps (Koko the Clown), it was at this point that Bray decided to focus more on educational and industrial films. In 1929, Lantz went on to form his own studio, where he began production for Universal on shorts starring the former Disney character Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. Lantz, of course, is best remembered for Woody Woodpecker.

DINKY DOODLE LOST AND FOUND (1926). Dir. by Walter Lantz. When a thuggish – but strangely polite – kidnapper pursues a beautiful damsel, cartoon director Walter Lantz intervenes in the chase. By the early 1920s, Walter Lantz was a budding animator at Bray, with a directorial position on the horizon. Lantz had cut his teeth as a teenager working at the International Film Service cartoon studio in the late teens, whose animation production of the Hearst-owned comic characters was eventually handled by Bray. For a variety of reasons, Bray’s major players such as Earl Hurd, Max Fleischer, and others had all left the studio by 1921. Along with director Vernon Stallings, Lantz began working on Bray’s reincarnation of Col. Heeza Liar in 1923, and by 1924, Lantz took center stage at the studio with his introduction of the Dinky Doodle series. Lantz proved to be Bray’s final director of cartoons; by 1927, the studio formally withdrew from producing animation. With other studios producing more critically-acclaimed series like Felix the Cat and Inkwell Imps (Koko the Clown), it was at this point that Bray decided to focus more on educational and industrial films. In 1929, Lantz went on to form his own studio, where he began production for Universal on shorts starring the former Disney character Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. Lantz, of course, is best remembered for Woody Woodpecker.

Spread the word – See all of the films above Monday October 6th on Turner Classic Movies – “Back To The Drawing Board”

Tom Stathes (right) talks Bray with Robert Osborne (left)

Tommy Stathes is an animation historian specializing in silent era cartoons. He resides in New York and frequently holds public screenings throughout the city. You can read more about his work, his collection and his research on his website:

Tommy Stathes is an animation historian specializing in silent era cartoons. He resides in New York and frequently holds public screenings throughout the city. You can read more about his work, his collection and his research on his website:

Tom:

I can hardly wait to see the finished product! I know what I’ll be doing Oct. 6th! Thanks to you and your colleagues for giving us animation fans another great reason to watch TCM!

I have cancelled all that I have (or will have) for Monday nite!! It will be just like Monday Night Football…..except important….and entertaining!!!

Thanks for all the great research. I hope they don’t windowbox them this time.

Hi Tom,

Unfortunately, I don’t have cable TV! Are these broadcasts going to be sold as Blu-ray or DVD sets?

Hi Dan…the quick answer: more or less!

Can’t wait to see this…

I’ll never be the fan of Bray that you are, Tom, to me most of his studio’s cartoons look like slide films, but every good wish to you and I hope you get lots of viewers. TCM doesn’t care about ratings, do they? Maybe that’s why they can run Bray cartoons and other obscurities without trepidation!

I feel the same way Mark. I never could quite get into silent cartoons at all on the same level as Tom has. It certainly takes a certain person who understands the history of the medium to see to it’s preservation.

TCM doesn’t care about ratings, do they? Maybe that’s why they can run Bray cartoons and other obscurities without trepidation!

Any excuse to get people to watch “Magic Boy” is fine with me! Did that film ever end up in the syndie UHF afternoon movie pile? It’s hard to imagine seeing that as a Pan & Scan copy but I wouldn’t be surprised if that was the case.

Tom, I was wondering if you are familiar with the work of Vladislav Starevich*? (*Also spelled Wladislaw Starewicz)

Great work Tom!

What channel will this TCM program be on?

That is something we can’t tell you. Every cable or satellite system has its own channel line up – so TCM maybe on channel 132 or 357 or some other channel number in your area. Check your local area channel listings.

In my opinion, the Bray Studios were notable for the talents who passed thru its doors, and its own story parallels that of silent animation itself. John Bray himself, like Winsor McCay, was an illustrator and fantasist, also something of a Victorian-era moralist, though not really a humorist; a film like “Artist’s Dream” points back more to the French trick films and American and British lightning-cartoonist films than what was to come.

Paul Terry and Max Fleischer had some of those traits too, but with a more humorous inclination comparable to the comic strips of the time; and both would carry that further in their individual ways.

Walter Lantz (with Clyde Geronimi) was probably the first Bray director/animator to emphasize the kind of sight-gag slapstick comedy found in the contemporary live-action short comedies of Roach and Sennett, and other cartoon series like Felix the Cat.

It wasn’t a big jump from there to the wacky humor of the early talkie cartoons.

(And as the sun set on the Bray Studio as a theatrical cartoon maker, John Bray’s silent era associates, Terry, Fleischer, and Lantz would become major animation names in the “talkie” years ahead.)

Can’t wait for this!

Of course, Monday is the biggest Tv night in my household – had to completely overhaul my PVR to fit all this in… I’m sure it’s more than worth it!

I know what _I’ll_ be doing tomorrow night, too!

Jerry Beck is right. The channel TCM is on varies by cable/satellite provider. Here in eastern Prince William County, VA (south of Wash D.C.), TCM regular is channel 44 – HD is channel 890. Just look through the 8,658 channels…

Trivia Time: Dinky Doodle’s dog’s name is Weakheart. Where does that name come from? Well, buoys and gulls, I’ll tell you. Rin-Tin-Tin, the popular Warner Bros. dog star in the 1920s, generated a LOT of copy-cats (copy-dogs?). You know, if it’s worth doing, it’s worth overdoing. One of the dog stars that capitalized on Rin-Tin-Tin’s popularity in the movies was a movie dog named Strongheart. So… Walter Lantz just turned that around a little bit, and…

So now you have learned your Thing For The Day.

As I mentioned above, I don’t have cable, but a friend of mine does and he was going to DVR them so we could watch them together the next day, but forgot to do so until about 10:30. So we ended up with 1 hour and 15 minutes of the Winsor McKay portion — which cut out right in the middle of the “Pet” cartoon! So I’m guessing that was originally an 1:30 or longer in timing — whereas I thought they would all be one hour long. Just wanted to make sure, though, that the earlier viewing showed all of the Winsor McKay cartoons? Canemaker had said the next portion would show 3 cartoons. The first was the Rarebit Bug Carnival, and the second was the Rarebit Pet (or growing dog). Did the third complete cartoon get shown in the earlier segment? And did they ever get to the 2nd version of “Gertie”, of which he said only a snippet survived?

Are these Winsor McKay cartoons going to be released on Blu-ray or DVD?

Tom, I only got to catch the last few minutes of your section. Was that a Blu-ray of the cartoons shown on the program that you were holding up at the end? If so, where can we purchase that?

My friend really likes this host for TCM, but I have to say I found him a bit stodgy, and was wishing that he and John Canemaker, and you, Tom, had all been a bit more (excuse the pun) “animated” in your conversation!