Donald Duck in Close-Up #6

Tomorrow, the day after this post appears, will be Tuesday, the 9th of June. As Disney fans know, the 9th of June is Donald Duck’s birthday. Right? Well …

The idea of a fictional cartoon character having a “birthday” is, of course, a whimsical notion to begin with. But the Disney studio has embraced it ever since the early 1930s, when a random date was selected each autumn and celebrated as “Mickey Mouse’s birthday,” with an accompanying promotional campaign. Never mind that the date tended to change from one year to the next; the campaign invariably brought a fresh wave of public affection for Mickey, and that, in turn, prompted increased theatrical bookings of Mickey Mouse cartoons.

Decades later, Dave Smith, the founder of the Walt Disney Archives, mounted a concerted effort to establish, once and for all, Mickey’s authentic “birthday”—that is, the date on which he was actually introduced to movie audiences. Smith settled on November 18th, 1928, the day on which Steamboat Willie opened at the Colony Theater in New York. He was right, of course; that date truly was an historic occasion, the beginning of Walt’s and Mickey’s joint success story. Thanks to Smith’s efforts, today’s Disney fan continues to recognize November 18th as Mickey’s official day.

Decades later, Dave Smith, the founder of the Walt Disney Archives, mounted a concerted effort to establish, once and for all, Mickey’s authentic “birthday”—that is, the date on which he was actually introduced to movie audiences. Smith settled on November 18th, 1928, the day on which Steamboat Willie opened at the Colony Theater in New York. He was right, of course; that date truly was an historic occasion, the beginning of Walt’s and Mickey’s joint success story. Thanks to Smith’s efforts, today’s Disney fan continues to recognize November 18th as Mickey’s official day.

And what about Donald Duck? Given his meteoric popularity, which at times has eclipsed that of Mickey himself, surely Donald was entitled to the same level of recognition. And, indeed, Disney did follow suit with another promotional “birthday” campaign in the 1930s. We’ve already observed in this space that the studio and its distributors designated Friday the 13th—any Friday the 13th—as Donald’s birthday. This made for an annual schedule even more erratic than Mickey’s, and brought the same benefits in the form of special bookings of Donald’s cartoons in theaters.

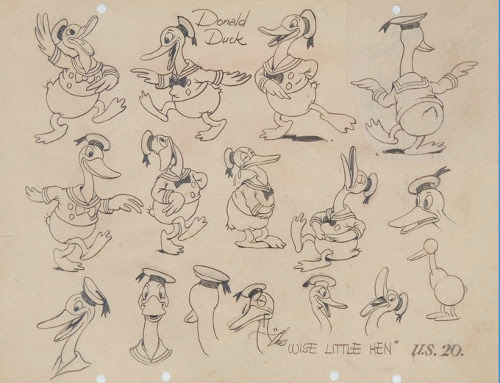

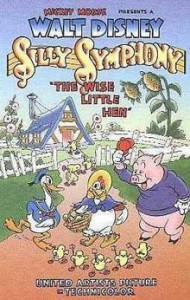

But in later years, when it came to establishing an authentic historical date for Donald’s introduction to audiences, the situation became more complicated. On the surface it seemed simple enough: Donald’s first screen appearance was in the Silly Symphony The Wise Little Hen, and Disney’s distributor, United Artists, officially released the film on June 9th, 1934. Accordingly, legions of Disney fans have marked the 9th of June as Donald’s birthday each year, and undoubtedly will do so again this year.

By the time that date rolled around in 1934, however, Donald was already becoming well known by the general public. There’s a common misconception that the “release date” of a movie is the day that movie is first shown in theaters. That was certainly my own understanding at one time. But while Russell Merritt and I were working on Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series, we learned otherwise. In compiling the release dates and theatrical openings of the Silly Symphonies, we discovered that release dates—at least for short subjects, at least in the 1930s—were essentially meaningless. Often it seemed that United Artists and other distributors, pressed by trade papers to supply release dates for their short subjects, simply selected a date at random out of thin air. The theatrical premiere of a given short might actually have occurred weeks before the designated date.

By the time that date rolled around in 1934, however, Donald was already becoming well known by the general public. There’s a common misconception that the “release date” of a movie is the day that movie is first shown in theaters. That was certainly my own understanding at one time. But while Russell Merritt and I were working on Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies: A Companion to the Classic Cartoon Series, we learned otherwise. In compiling the release dates and theatrical openings of the Silly Symphonies, we discovered that release dates—at least for short subjects, at least in the 1930s—were essentially meaningless. Often it seemed that United Artists and other distributors, pressed by trade papers to supply release dates for their short subjects, simply selected a date at random out of thin air. The theatrical premiere of a given short might actually have occurred weeks before the designated date.

In 1934, when The Wise Little Hen was produced, the Disney studio enjoyed a special relationship with New York’s Radio City Music Hall. Disney’s Silly Symphonies, produced in Technicolor, had long been recognized as the elegant zenith of animated cartoons; in Russell’s phrase, “the Tiffany line.” Radio City Music Hall, scarcely a year after its opening, was acknowledged as the most prestigious motion picture theater in the world. Accordingly, a pattern had been established: the Disney studio issued a new Silly Symphony; United Artists announced a release date; and then the cartoon was given a special debut, one or two days before that date, at the Music Hall. The Wise Little Hen followed this pattern: announced for release on Saturday, June 9th, it was unveiled at Radio City on Thursday the 7th (on a bill with the Columbia feature Sisters Under the Skin, starring Elissa Landi and Frank Morgan).

But that wasn’t all; Donald anticipated June 9th by more than that two-day gap. Long before The Wise Little Hen was completed, the Disney studio realized that it had an exciting new cartoon star on its hands. The leading press release in the film’s pressbook carried the headline DONALD DUCK A NEW STAR, and Walt himself took every opportunity to spread the word about his colorful new character. As a result, Donald’s “rollout” took place gradually. On Thursday, the 3rd of May, more than a month before United Artists’ official release date, The Wise Little Hen was shown at Los Angeles’ Carthay Circle Theater as part of a special benefit program for the California Commission for the Protection of Children and Animals. (On the same program was the Mickey Mouse short Gulliver Mickey, which likewise had not yet been officially released.)

Five days before that showing, Donald was heard before he was seen. On Sunday, April 29, the popular bandleader Raymond Paige performed the entire score of The Wise Little Hen on his radio program California Melodies, broadcast by station KHJ. Along with Paige’s orchestra, the performance featured a vocal trio called The Three Rhythm Kings, and the “original character voices” from the cartoon—i.e. Florence Gill as the hen, and Clarence Nash doubling as both Peter Pig and Donald Duck. This was a natural promotional opportunity, not only for the cartoon, but also for Donald, whose voice was such an integral part of his character development. And it was a familiar working environment for Clarence Nash, who took to radio like a Duck to water. Moreover, Nash already had a history with this particular radio station. KHJ was a major broadcast center and, at the time, the Los Angeles flagship station for the CBS network. It was reportedly Nash’s performance on a KHJ program that had brought him to Walt Disney’s attention in the first place.

Five days before that showing, Donald was heard before he was seen. On Sunday, April 29, the popular bandleader Raymond Paige performed the entire score of The Wise Little Hen on his radio program California Melodies, broadcast by station KHJ. Along with Paige’s orchestra, the performance featured a vocal trio called The Three Rhythm Kings, and the “original character voices” from the cartoon—i.e. Florence Gill as the hen, and Clarence Nash doubling as both Peter Pig and Donald Duck. This was a natural promotional opportunity, not only for the cartoon, but also for Donald, whose voice was such an integral part of his character development. And it was a familiar working environment for Clarence Nash, who took to radio like a Duck to water. Moreover, Nash already had a history with this particular radio station. KHJ was a major broadcast center and, at the time, the Los Angeles flagship station for the CBS network. It was reportedly Nash’s performance on a KHJ program that had brought him to Walt Disney’s attention in the first place.

We can gain a sense of that California Melodies broadcast by listening to Raymond Paige’s Victor recording of “The Wise Little Hen,” recorded in Hollywood ten days earlier on April 19, and featuring the same vocalists. Here the story is condensed to three and a half minutes in order to fit on a single 78 rpm side, but still offers a generous sampling of Leigh Harline’s score from the film. (Notably, it does not include Gustav Lange’s “Flower Song,” a short passage of which was heard in the film’s score, and for which the studio had to obtain a license.) And even in this compressed version of the story, note that Donald gets the last word!

For those who like to keep track, this record was issued in the U.S. on Victor 24616-A and in England on British HMV B-6555. Both releases were backed with Paige’s similar recording of “The Grasshopper and the Ants,” and both were made from the same master, mx. PBS-79176-2.

In short, as early as mid-April 1934, the public was starting to become acquainted with Donald Duck. Tomorrow, as Disney fans inevitably mark the occasion of Donald’s “birthday,” it’s well to remember that he actually had a protracted delivery, one that lasted for nearly two months! One date will do as well as another; the important thing is that he was born, and has given us boundless enjoyment for 86 years and counting. That’s something to celebrate!

Next Month: The Plastics Inventor

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

I’m sure you already know that long before Russell Merritt called Disney’s Silly Symphonies “the Tiffany line”, Paul Terry was fond of saying: “Disney is the Tiffany’s in this business; I am the Woolworth’s.”

Thank you, Paul. Yes, that’s true — but Russell, besides being one of the most brilliant film historians in the world, is also a good friend, and I like to give him a little space when I can. Also, in his defense, when he used that phrase he was distinguishing the Silly Symphonies, not only from the work of other studios, but also from other contemporary Disney cartoons — i.e. Mickey Mouse. I’m not going to get into a dispute here, because of course we all love Mickey too, and he was wildly popular in the early 30s. But it’s true that his films didn’t get the prestige treatment that the Symphonies did, until the Mickey series started appearing in Technicolor in 1935.

Yes, I believe the Mickey cartoons were referred to as “potboilers” at the studio.

Regarding this part:

“Decades later, Dave Smith, the founder of the Walt Disney Archives, mounted a concerted effort to establish, once and for all, Mickey’s authentic “birthday”—that is, the date on which he was actually introduced to movie audiences. Smith settled on November 18th, 1928, the day on which Steamboat Willie opened at the Colony Theater in New York. He was right, of course; that date truly was an historic occasion, the beginning of Walt’s and Mickey’s joint success story. Thanks to Smith’s efforts, today’s Disney fan continues to recognize November 18th as Mickey’s official day.”

Michael Barrier has pointed out that the date had actually been established in his magazine Funnyworld two years before Smith decided that this was Mickey’s official birthday (http://www.michaelbarrier.com/WhatsNewArchives/2016/WhatsNewArchivesAugust16.html#overduereviews):

“A quibble: there’s an essay by the retired Disney archivist, Dave Smith, in which he says: “One of the things I did was to officially determine in 1973 that Mickey Mouse’s birthday was November 18, 1928, at the Colony Theater in New York.” Actually, that date had been established in 1971, through my Carl Stalling interview in Funnyworld No. 13. I pointed out in a note to that interview that the September date for Mickey’s birth that Disney had used for years was incorrect. The interview included as evidence a Powers Cinephone ad with dated quotations from multiple newspapers and trade papers, all clearly identifying November 18 as the premiere date.”

Thank you! I stand corrected. We all owe a great debt to Dave Smith, but needless to say, we *also* owe a great debt to Mike Barrier. I’m one of Mike’s greatest admirers and would never intentionally deny him any credit for any of his accomplishments. Thank you for setting the record straight.

“The leading press release in the film’s pressbook carried the headline DONALD DUCK A NEW STAR…”

Mr. Kaufman: it would be great to see an image of that!

Hi JB, I’m enjoying these posts of yours, and looking forward to the Donald book. In doing research for my eventual book on cartoon voices, I am noticing all sorts of odd things such as the reference you make in your Mickey Mouse book (page 188) to the McKay book “Adventures of Mickey Mouse,” with a reference to a Donald Duck a few years before he became a screen star. I imagine Disney with his steel trap memory retaining any name like that in the back of his mind, always aware of possible future characters for the screen. It’s also mentioned in a sentence in Charles Solomon’s 1989 Enchanted Drawings which notes, “Although there was a reference to Donald Duck as one of Mickey’s friends in the 1931 book The Adventures of Mickey Mouse, the character didn’t appear on the screen until The Wise Little Hen, three years later.” My question here is: are you aware if the Donald name was just mentioned as a Mickey buddy in text, or was there a drawing of the embryonic Donald in that book?

There’s a large drawing of a humanized duck, generally accepted as this Donald Duck, on the back cover. You can see what he looked like here:

https://d23.com/donald-duck-early-appearance/

The character names from The Adventures of Mickey Mouse, Book 1 were carried on into Britain’s Mickey Mouse Annual #3 in 1932, where “Donald Duck” was referenced in another rundown of Mickey’s pals, and that time he looked like this:

http://kayaozkaracalar3.blogspot.com/2009/12/british-follow-up-to-donalds-pseudo.html

Hi, Keith, and thanks for your note. To answer your question, no, there’s no drawing of Donald in the book. And yes, the name Donald Duck is mentioned only as one of Mickey’s barnyard friends, and it’s part of a list of alliterative names that also includes Henry Horse, Carolyn Cow, Patricia Pig, and Robert Rooster. Also, interestingly enough, “Clara Cluck, the Hen”! I frankly think the mention of Donald Duck in this 1931 storybook is just a coincidence — a really nice coincidence, under the circumstances, but nothing more than that. Of course you’re right, Walt did have that steel-trap memory, and it’s entirely possible that the names “Donald Duck” and “Clara Cluck” lodged in his subconscious in 1931, both to be retrieved a few years later.

Thanks JB and David, that is good information and images to fill still another gap in my knowledge. Much appreciated.

The 1931 Donald Duck is wearing pants — and not just any pants, but Lederhosen! And a Tyrolean hat! I know that Clarence Nash spoke German, but could he yodel?

Nash himself probably could yodel, but yodeling in Donald’s voice must have been more of a challenge. He comes close in “Alpine Climbers” (1936).

Hey JB, it sounds like the studio knew Donald would be a star right from release. Doesn’t that contradict Peter Pig originally being planned to be the breakout character? Or is that just a myth?

Thank you for your note. No, I think that must be a myth. Actually, you may know that the original Disney story outline for the film projected *three* lazy neighbors for the hen: Peter Pig, Donald Duck, but also a Tom Turkey. The turkey was cut from the story within the first month of story development. But even when all three characters were involved in this one cartoon, the studio was making more extended plans for the talking duck character. David Gerstein and I have discovered that the film that eventually became “Orphans’ Benefit” actually seems to have started development *before* this one did.