Donald Duck in Close-Up #3

The sudden, spontaneous popularity of Donald Duck in the mid-1930s was a blessing to the Disney studio in more ways than one. Mickey Mouse was still an international favorite, and would remain the Disney figurehead, but he had already been pigeonholed as a “nice guy.” Violent slapstick gags, a common staple of animated cartoons, were increasingly restricted in Mickey’s films. No such problem with Donald Duck!

Almost from the beginning the Duck had been established as an irritable, combative character, and therefore well suited to roughhouse comedy. Falls, chases, collisions with low-hanging branches, explosions, hockey pucks and other objects fired into his open mouth—whatever slapstick misfortunes the story department could dream up, Donald was fair game. He was dragged through a pond, slammed into walls, and crushed by falling rocks in The Fox Hunt; hanged by the neck in The Hockey Champ; chased by a whale in The Whalers and by a shark in Sea Scouts; plunged headfirst into a pail of milk in Old MacDonald Duck, yanked into a stamper and smashed into a “Duck ingot” in Donald’s Gold Mine; and audiences roared with laughter.

Almost from the beginning the Duck had been established as an irritable, combative character, and therefore well suited to roughhouse comedy. Falls, chases, collisions with low-hanging branches, explosions, hockey pucks and other objects fired into his open mouth—whatever slapstick misfortunes the story department could dream up, Donald was fair game. He was dragged through a pond, slammed into walls, and crushed by falling rocks in The Fox Hunt; hanged by the neck in The Hockey Champ; chased by a whale in The Whalers and by a shark in Sea Scouts; plunged headfirst into a pail of milk in Old MacDonald Duck, yanked into a stamper and smashed into a “Duck ingot” in Donald’s Gold Mine; and audiences roared with laughter.

In line with this rough treatment, the Disney writers saddled Donald with another affliction: he was prone to bad luck. As early as 1935, Bill Cottrell suggested to Walt Disney that Donald’s “birthday” could be celebrated on Friday the 13th. For years Disney’s distributors had mounted an annual promotional campaign around Mickey Mouse’s “birthday,” arbitrarily selecting a random date during the autumn months. Now Cottrell suggested a similar campaign for Donald, tying his natal day to Friday the 13th—meaning, of course, that it would fall in a different month every year. “It sounds like a good crazy angle,” Roy Disney wrote in a memo, “and one which would fit Donald’s personality very well.” In March 1936, 84 years ago this month, Disney and United Artists staged a nationwide “party” for Donald on the traditionally unlucky day.

That was only the beginning. As Donald’s adventures continued, the Disney writers found more opportunities to link him with the number 13. In his daily comic strip, Donald was sometimes depicted as an apartment dweller—living in apartment 13. He frequently was seen driving around town in a little roadster, and comics artist Al Taliaferro gave him license plate number 313. When the U.S. entered World War II, the Duck appeared onscreen in Donald Gets Drafted: his draft notice, shown in closeup, was order no. 13, and he dutifully reported to draft board number 13. In 1944 The Three Caballeros opened with a giant gift package sent to Donald by his Latin American friends “on his birthday, Friday the 13th.” A full ten years later, on “The Donald Duck Story” episode of the Disneyland TV program, Walt himself offered a slightly whimsical account of Donald’s career, with a tongue-in-cheek claim that the character had been created on Friday the 13th.

And Donald’s association with bad luck wasn’t just symbolic. I’ve written elsewhere about Mickey Mouse as the “heir apparent” of the American comedy tradition in the 1930s, but Donald inherited a different aspect of that tradition: the comedian as the butt of the gag, the eternal fall guy. Somehow his disagreeable nature created a kind of instant karma in which he brought on himself one calamity after another. As the Duck cartoons continued and became more sophisticated, his troubles went beyond slapstick mayhem and embraced misfortunes that were more subtle, but just as vexing. Several of the featured Disney characters appear in The Fox Hunt, but it’s Donald who thinks he’s trapped the fox in a hollow log, and ends the picture by reaching inside and pulling out a skunk instead. In Donald’s Off Day he heads out on a beautiful morning to play golf, only to see the sky erupt in a torrential downpour the instant he steps out the door. In several 1940s cartoons he asks nothing more than a night’s sleep, but is kept awake by a noisy clock, a dripping faucet, or some other nagging irritation that drives him into a squawking fury by reel’s end.

Disney comic-book legend Carl Barks picked up on this theme and offered his own twist on the idea in the late 1940s. Barks introduced a new character, Donald’s cousin Gladstone Gander, whose luck was so unbelievably good that Donald’s bad luck seemed even more outrageous by comparison. In one story after another, Gladstone enjoyed impossibly good fortune at Donald’s expense, while his hapless cousin took all the lumps. “Maybe Gladstone is right,” Donald moaned in one story. “He’ll always be lucky, and I’ll always be unlucky!”

Disney comic-book legend Carl Barks picked up on this theme and offered his own twist on the idea in the late 1940s. Barks introduced a new character, Donald’s cousin Gladstone Gander, whose luck was so unbelievably good that Donald’s bad luck seemed even more outrageous by comparison. In one story after another, Gladstone enjoyed impossibly good fortune at Donald’s expense, while his hapless cousin took all the lumps. “Maybe Gladstone is right,” Donald moaned in one story. “He’ll always be lucky, and I’ll always be unlucky!”

The climax—or nadir—of Donald’s relationship with bad luck can probably be found in the theatrical short Donald’s Lucky Day. By the time this cartoon was produced in the late 1930s, audiences were familiar enough with the Duck and his world to know that the title could be taken ironically. Sure enough, the story is set on Friday the 13th, and the film’s action—animated by a full complement of the studio’s top “Duck men”—rings a series of exquisitely tuned variations on the theme of Donald’s misfortune.

Like many of the classic Duck films of this period, Donald’s Lucky Day speaks for itself. What is not apparent today is the special care with which the film was released to theaters. Donald’s Lucky Day was produced during 1937–38, and was ready for release by the end of May 1938. But it was made to order for a Friday the 13th release date, and the 13th would not fall on a Friday until the following January.

DONALD’S LUCKY DAY

RM 17

Copyright 7 December 1938 by Walt Disney Productions, Ltd.: MP8945

Released 13 January 1939 by RKO Radio

MPPDA certificate 3821

Director: Jack King

Music: Ollie Wallace

Story directors: Harry Reeves, Carl Barks

Layout: Jim Carmichael, Bill Herwig

Animation: • Ed Love (boss and stooge in opening scenes; radio on handlebars; Duck rides bicycle

down sidewalk in perspective)

• Jack Hannah (Duck rides bicycle and sings in opening scenes; Duck listens to radio

announcer, crashes into mirror and applecart and looks at clock tower)

• Johnny Cannon (Duck parks bike and walks to door; exchange with gangster, Duck runs

out)

• John McManus (Duck runs around corner, jumps on bike, and rides with package under

arm; duck retrieves box and runs after mouse; Duck on hook drenched by water and covered with fish; Duck anticipates and is swarmed by cats in closing scene)

• Paul Allen (Duck meets cat and tries to evade it; cat lies down on box and Duck tries to

scare it away with windup mouse; CU bomb and clock inside package)

• Al Eugster (Duck runs behind lumber pile; first part of Duck and cat on plank, until Duck

hangs from plank)

• Don Towsley (last part of Duck and cat on plank; package comes unwrapped)

• Dick Lundy (CU unwrapped clock and bomb; Duck hangs on hook, cat bats at bomb)

Ken Peterson (cats pop up around dock and from behind barrels)

Efx animation: Sandy Strother (fog and reflections on water in opening scene; crash of mirror)

• Cornett Wood (perspective shot of pilings in water; bomb falls in water, explosion, water

washes over dock)

Assistant director: Jim Handley

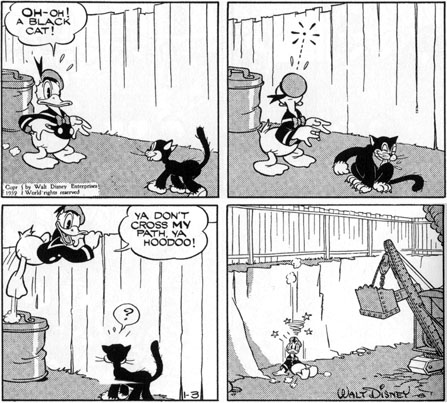

Disney actually withheld the short from release for more than seven months! As the designated release date approached, Disney mounted a special promotional campaign, including tie-in gags in the daily Donald Duck comic strip. The strip’s writer and artist, Bob Karp and Al Taliaferro respectively, frequently coordinated their gags with the studio’s current film offerings. Here, during the first week of January 1939—the week before Donald’s Lucky Day would be released to theaters—the newspaper strip presented a full week of gags involving jinxes or superstitions. One installment actually featured an appearance by the black cat from the film, and the same cat later became a recurring character in the strip, invariably signaling some fresh disaster for Donald.

The Duck’s permanently unlucky status has persisted throughout the years, and is still with him today. When the studio introduced a new theme song to underscore the opening titles of his cartoons, the line “Who gets stuck with all the bad luck?” was only a rhetorical question. Donald’s fans already knew the answer.

Next Month: Postwar Donald

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

Clara Cluck in La Traviata? No, you wouldn’t want to be stuck behind a pillar for that!

Thanks for another “ducky” post, appearing appropriately in a month with a Friday the 13th in it. I never thought of Donald as unlucky — most of his misfortunes seem well-deserved — but you make a good case. However, it’s not his bad luck that’s been on my mind lately.

When I was around ten I got a book for Christmas called BIRD BEHAVIOR by John Sparks. I still have it, and just yesterday I was consulting it when I had one of those moments where you look in an old book for the umpteenth time and see something you never noticed before.

At the beginning of the chapter “The Language of Birds” is an illustration of Donald Duck making various facial expressions, with the caption: “Cartoonists give birds muscular, expressive faces to make them communicate the ‘human’ way. In fact they have a much different ‘language’.” One thing that struck me was that in the picture where Donald had his mouth open, he had a small, triangular tongue like that of a songbird. Ducks and geese have fleshy, rounded tongues that conform to their bills and are shaped not unlike ours. The other thing I noticed was that Donald seemed slightly off-model; for example, his collar was a featureless blue donut, without the piping and bow tie of his sailor suit. When I looked for acknowledgement of the Walt Disney Company and found none, I realised: this Donald Duck was an unauthorised, illegal knock-off!

I wondered whether this weird tongue was an original feature of Donald’s design or an invention of the illustrator. But by chance, the very next day you provided me with the opportunity to watch “Donald’s Lucky Day” here on Cartoon Research — and the first thing I saw was Donald’s face with the triangular songbird tongue! I had never given any thought to Donald Duck’s tongue before, and I’m sure you haven’t either, but it puzzled me greatly. After all, if the facial features of cartoon birds are designed to convey human expressions, as the book pointed out, then why would Donald have a tongue that is not only less like a human’s, but less like a real duck’s?

I’m speaking rhetorically, of course. But if, in the course of your research, you stumbled across any information on the design and development of Donald Duck’s triangular tongue and decided to leave it out of your book because you thought that nobody could possibly be interested in it, then may I disabuse you of that notion.

Sorry to expatiate on an inconsequential matter that has nothing to do with Donald’s bad luck. Though I’ve been told that in India, biting your tongue is supposed to bring bad luck. Good thing Donald doesn’t have any teeth.

Thank you, Paul, for this thoughtful response. It’s appreciated more than you know. I can make no claims as a birder myself, but I happen to have a brother who is a world-renowned ornithologist, and I’ve picked up at least a heightened appreciation of birds from him. So I’m intrigued by your observation. To answer your question, I’ve seen no primary documents to indicate that the artists put a lot of thought into the design of Donald’s tongue. But of course you’re right, from the beginning — even before Fred Spencer’s redesign of the character — even at the time of “Wise Little Hen,” Donald did have that little triangular tongue. When Spencer did do his redesign, he wrote at length on the Duck’s various physical features but never mentioned the tongue at all. Sorry not to have a better answer than this, but thank you for making me think about this subject!

Oh, my goodness! Is Kenn Kaufman your brother? He’s a legend!

Yes, he is … my brother, AND a legend.

Donald Duck also has the dubious distinction of being the Disney character with the longest rap sheet, with the possible exception of Peg Leg Pete or the Beagle Boys.. Many of his adventures, especially in print, have concluded with Donald on the wrong side of the law, most notably the epic tale “Lost in the Andes,” which ends with a police car en route to arrest a rampaging duck. Several of the best comic strip gags have culminated with a scene of Donald in jail. This gag works especially well when he’s clearly been set up by someone else–as when he attempts to replace a mailbox stolen by one of the nephews and is rewarded by getting locked up. Or when he goes to jail for using the sidecar of an officer’s motorcycle to take a cooling bath on a sweltering hot day. Or when he “corrects” a youngster in the same fashion a police officer has “corrected” him, by a spanking–after the child has assaulted the officer with a snowball and Donald has gotten the blame. The officer assumes the child is innocent and Donald ends up looking sadly out from behind the barred window of a jail cell. Talk about bad luck!

Thank you, Frederick! Yes, of course you’re right, Donald comes in for his share of punishment even when, or especially when, he’s not guilty. And, as you point out, on more than one occasion that translates into actual jail time.

The question isn’t just rhetorical in the Donald Duck theme song, it answers the question. “Who gets stuck with all the bad luck? No one but Donald Duck”

Us Donald Duck fans did already know the answer of course to who gets all the bad luck. You notice how in many Donald Duck cartoons, he never even gets the chance to eat something he’s wanting, grabbing, buying, cooking, etc., some mishap keeps getting in the way of even letting him take one bite of whatever food he’s hungry for