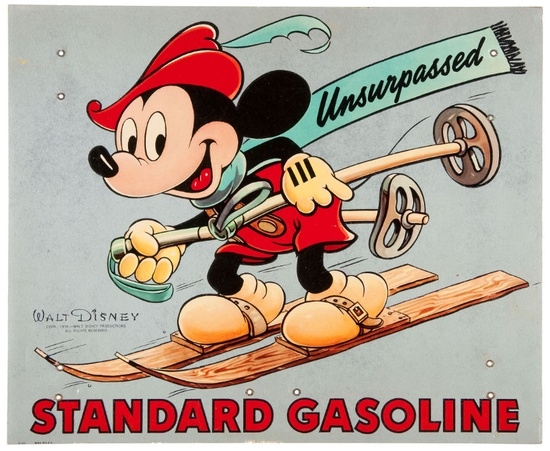

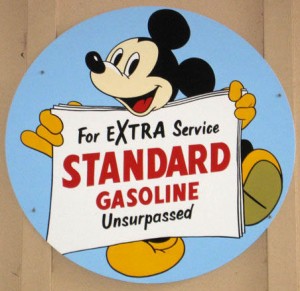

Not all of the nontheatrical Disney cartoons were educational or public-service films. Some were sponsored films, undertaken for commercial sponsors who were willing to pay to have the prestige of Disney characters and Disney animation associated with their products. During the studio’s Golden Age these sponsored cartoons were rare, and were produced for such specialized use that they’re seldom shown today. As a result, they have a cachet of scarcity that makes them fascinating to today’s viewer. In this post we’re looking at one such cartoon, produced for special showings at Standard Oil sales conventions in 1939. This one is doubly fascinating: not only does it have that rarity factor, it also contains some choice nuggets of recycled animation from earlier Disney films.

STANDARD PARADE FOR 1939

2602

Delivered (Standard Oil) March 1939

Director: Riley Thomson

Music supervision: Charles Wolcott

Layout: Jim Carmichael

Reworked animation:

• Sam Cobean (Mickey, Minnie, trumpeters, Sleepy)

• Rex Cox (drummers)

• Ozzie Evans (bass drummer and helpers)

• Amby Paliwoda (sweepers)

• Scott Whitaker (rug roller, Sneezy)

• Bob Carlson (Doc, Grumpy, Bashful)

• Art Elliott (Happy)

• Volus Jones (Dopey)

• Ken Peterson (Toby Tortoise)

Original animation:

• Johnny Cannon (Donald Duck)

• Nick De Tolly (Pluto, Big Bad Wolf)

• Eddie Strickland (Goof)

• Claude Smith (Three Little Pigs)

Assistant director: Jack Bruner

Unit secretary: Dorris Pugsley

The Disney studio contracted late in 1938 to participate in Standard’s advertising campaign during the coming year. This film was only one part of the campaign; the studio also committed to a series of newspaper ads and other promotional aids in which Disney characters extolled the virtues of Standard Oil. Riley Thomson, a former animator, was appointed as the director of The Standard Parade. It provided him with valuable experience, and shortly afterward he became a regular director in the Disney shorts department.

The Disney studio contracted late in 1938 to participate in Standard’s advertising campaign during the coming year. This film was only one part of the campaign; the studio also committed to a series of newspaper ads and other promotional aids in which Disney characters extolled the virtues of Standard Oil. Riley Thomson, a former animator, was appointed as the director of The Standard Parade. It provided him with valuable experience, and shortly afterward he became a regular director in the Disney shorts department.

There’s no real story in The Standard Parade; true to its title, it’s simply a parade of characters marching past the camera with signs and banners. What makes it especially interesting to the Disney enthusiast is that the animation is drawn from multiple sources. As the credit list above suggests, most of the parading characters are reworked from scenes in previous well-known Disney films—along with some original animation, combined in an ingenious exercise in patchwork.

The provenance of the opening scenes is especially interesting. It dates back to 1931, when the studio produced a Silly Symphony titled Mother Goose Melodies. The opening scenes of that film depict a procession of characters marching past the camera as they escort Old King Cole to his throne. We see trumpeters, drummers, little lackeys who sweep the path and unroll a carpet, a flower girl who scatters petals, and more trumpeters, before King Cole himself finally makes an appearance. This 70-foot scene was animated by Ben Sharpsteen and makes use of anonymous, generic characters—except for the flower girl, a cow who closely resembles Clarabelle in the Mickey Mouse series.

Sharpsteen’s parade animation was seen again the following year, but only by a private audience of film-industry professionals. For the Academy Awards banquet in November 1932 (honoring the films produced in 1931-32), the Disney studio produced a special Technicolor trailer titled Parade of the Award Nominees. This very short film depicted caricatures of the year’s acting nominees, parading past the camera. These animated celebrities were preceded by an honor guard: Mickey Mouse as a drum major, Minnie carrying an announcement banner, and Sharpsteen’s company of pages and heralds, repainted in color.

Now, in 1939, the studio dusted off the opening animation from the Academy short and repurposed it for a third film: the Standard Oil ad. Riley Thomson parceled out the original drawings to a group of animators who redrew them according to the studio’s current standard. Sam Cobean’s reworking of the Mickey and Minnie scenes was perhaps especially significant, for in these scenes the characters appeared with newly redesigned eyes—pupils working inside an eyeball. This new Mickey design model had become official within the studio in 1938, but The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, the film originally intended to introduce his new look, wouldn’t reach the screen until the opening of Fantasia in November 1940. The Pointer, the theatrical short that did serve to introduce Mickey’s new design to movie audiences, wouldn’t be released until July 1939. In March 1939, then, as Standard Oil salesmen watched The Standard Parade, they were seeing an unofficial “preview” of the new Mickey Mouse—and Minnie too.

Still wearing his outsize drum major’s uniform, Mickey leads off the parade, followed by Minnie, her Academy Awards banner replaced by a new one promoting Standard Oil. Next come some of Sharpsteen’s parading characters from 1931, reworked in 1939 by five different animators. The procession is abbreviated this time—and, in fact, was further abbreviated during production: the original plan was to retain Clarabelle Cow in the new parade, and the job of reworking her animation was assigned to Al Bertino. By February 1939 she had been dropped from the lineup. In the finished version we see the trumpeters, the drummers, the sweepers, and the little character who unrolls the carpet, followed by a new assortment of characters who had not existed in 1932.The first of these are the Seven Dwarfs, from the recently released Disney feature Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and theirs is another fascinating case. Early in production of Snow White, one of the principal Dwarf animators, the great Bill Tytla, had animated a long closeup pan of the little men marching past the camera on their way home from the mine. This was a key scene in producing the feature. It established distinctive walks and other characteristics for each of the dwarfs, it served as a guide or template for other artists who drew the characters—and, in the general tightening and streamlining of the continuity, Tytla’s scene was itself cut from the film! Now the studio retrieved and repurposed it for The Standard Parade. Once again the dwarfs marched past the camera one by one, the picks over their shoulders replaced by signs spelling out the name STANDARD. Tytla’s original scene had shown the characters walking from screen left to screen right; now the artists reversed direction to show the dwarfs, in line with the rest of the procession, walking from right to left.

Dave Hand, who had been the supervising director of Snow White, now supervised Thomson’s work on The Standard Parade. At a meeting in January 1939, Hand surveyed Tytla’s original dwarf drawings. “Are you having all those redrawn?” he asked. “I think you’re crazy if you do. I’d send it through just as it is.” And, indeed, most of the dwarf action in The Standard Parade is essentially Tytla’s original animation, changed only in superficial details. The major exception is Dopey, who trails the other dwarfs with a new piece of business: carrying a four-way traffic sign, he rotates the sign so that the final two letters of the brand name, R and D, are visible to the camera.As the parade continues, we see one more recycled piece of animation: Toby Tortoise, in a scene originally animated by Dick Lundy for the 1934 Oscar winner The Tortoise and the Hare. The rest of the characters are newly animated for the Standard short: Donald Duck, Pluto, Goofy (replacing Pegleg Pete, who had originally been suggested for this spot), and, bringing up the rear, the Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Wolf. Donald Duck’s action is animated by Johnny Cannon, a Disney artist since 1927, who was by now established as one of the studio’s crew of “Duck men.” The Pigs are animated by Claude Smith, who had recently animated them in the theatrical short The Practical Pig.

Technically, the word “nontheatrical” is a bit of a misnomer here because Standard Oil staged its conventions in rented theaters in several cities. One wonders how many of the attendees realized the varied banquet of Disney animation that was being presented to them—in the space of less than two minutes.

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

About the “Parade of Award Nominees”- who is the fellow who turns green at around 2:06?

That’s Fredric March, making his transition from Dr. Jekyll to Mr. Hyde (and exercising a bit of creative license, since the Paramount “Jekyll & Hyde” was produced in black and white).

Just saw Stanchfield’s restoration of HELL’S FIRE, and Iwerks uses this same gag.

Would you do “Mickey’s Surprise Party” next week?

I would like to do that one, but I don’t have all the information about it! Hopefully I’ll be able to research it and write it up in the near future.

For anyone who’s interested, those Academy Award nominee caricatures are…

*Wallace Beery (and Jackie Cooper) from The Champ

*Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt from The Guardsman

*Helen Hayes from The Sin of Madelon Claudet

*Frederic March from Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

*Marie Dressler from Emma

And Walt, himself, received two awards at this ceremony:

*The inaugural award for best short subject (cartoon) for Flowers and Trees

*And a special award recognizing, then 4-year old, Mickey Mouse

The 1931-32 Academy Awards ceremony was the first to be nationally broadcast on radio, so I imagine people at home could at least hear the fun parade music from this short cartoon.

What a fun treat today! Thanks, J.B…

Thank YOU, J.P. I love this kind of context myself — I always think these Disney films are even more wonderful when we watch them in the context of other contemporary movies.

Assuming such a recording was ever kept of that, imagine how nth-gen hissy/staticy it might sound today, or to the people who first heard it over their radios.

Great post today. I really enjoyed both shorts (which, by the way, were included as extras on the Walt Disney Treasures DVDs). Interesting that the live action opening touting Disney’s success lasts about twice as long as the parade itself. As Jiminy Cricket would say, “What a build-up!”

I agree! I don’t know the provenance of that b&w opening piece — it does seem tacked on to the cartoon, and it would be interesting to know how it came about.

Hello Tony. Could you let me know in which one of the Treasure Tins may I find these two shorts. Than you, Martin

Interesting question here: Which Standard Oil company bankrolled this short?

When Federal “trust busters” broke up John D. Rockefeller’s original Standard Oil company in 1911, several companies were created, each of which was allowed to use the Standard name in a specific geographical area.

Some of these companies would not use the Standard name, even within their own territories. Others would come up with other names they would use to expand out of their limited geographical areas.

Two firms did use the Standard name on their signage and advertising. One was Standard Oil of Indiana, which used such names as “American”, “Amoco”, “Utoco” ad “Vico” wen getting out of their assigned Midwestern bailiwick. The other was Standard Oil of California, which would eventually become known as “Chevron” (and which is today’s Chevron Texaco conglomerate).

Also–what are “electroliers”?

It would appear to be “The Standard Oil Company of California”

Well that explains it. I didn’t expect SOHIO to be that good (outside of Ohio, they went by the name “BORON”).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_Oil_of_Ohio

Also–what are “electroliers”?

Best I could find is this… http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrolier

Perhaps it was a type of signage lighting used as advertising for a time.

Electroilers were either indoor chandeliers or streetlights where banners could be hung from.

As big a fan as I am of original Disney animation (and that goes back to when I was a child, more than 60 YEARS ago!), I had never heard of ANY of this!!! THANK YOU, Mr. J. B. Kaufman! :-D!

On the PARADE OF THE AWARD NOMINEES short, it really looks like Dick Heumer designed the caricatures, and animated the Wallace Beery and Jackie Cooper segment. The Cooper little boy looks and acts like Scrappy! I’m not sure of the exact date that Dick left Mintz for Disney, was it in 1932?

I recall reading reading in John Canemaker’s TWO GUYS NAMED JOE that the designs came from pre-Disney Joe Grant caricatures, without his or the magazine’s permission (can’t recall the magazine on the top of my head). Someone can happily correct me on that one if I’m wrong.

Sam Cobean became a magazine cartoonist – he was famous for his variations of the “out, into the snow” scene from D.W. Griffith’s “Way Down East” (father pointing out an open door to evict his unwed daughter and her baby).

Yes, this was made for Standard of California, the future Chevron Corp.