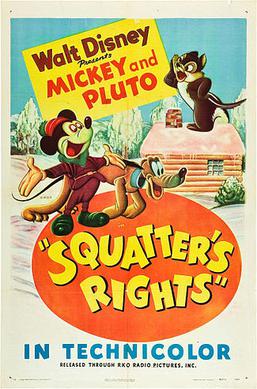

Most of my installments in this column have shied away from the studio’s primary bread-and-butter product during the 1930s and ’40s: the series of short cartoons released to movie theaters. The “other” Disney cartoons has meant the curiosities produced outside those series: the advertising, public-service, or nontheatrical educational films which the studio also produced, on the side. I’m breaking that pattern for this column. Squatter’s Rights was a regular entry in the Disney output of theatrical shorts—but it’s often overlooked today, and has so many odd unusual qualities that I think it qualifies as an “other” Disney cartoon in its own right.

Most of my installments in this column have shied away from the studio’s primary bread-and-butter product during the 1930s and ’40s: the series of short cartoons released to movie theaters. The “other” Disney cartoons has meant the curiosities produced outside those series: the advertising, public-service, or nontheatrical educational films which the studio also produced, on the side. I’m breaking that pattern for this column. Squatter’s Rights was a regular entry in the Disney output of theatrical shorts—but it’s often overlooked today, and has so many odd unusual qualities that I think it qualifies as an “other” Disney cartoon in its own right.

To begin with, it marks Mickey Mouse’s return to the screen at the end of World War II, after a virtual absence (except for reissues of older cartoons) during the war years. Immediately before the war the Disney animators had experimented with Mickey’s appearance, giving him dimensional ears that turned in perspective, and trying a loose, rangy style of movement sometimes known today as “drunk Mickey.” Walt Disney had responded favorably to these experiments at first, but had later changed his mind and discouraged such liberties. In Squatter’s Rights Mickey announces his return to an earlier style of appearance and movement—making the point unmistakably with a short block of scenes recycled from The Pointer (1939), a film that had preceded those graphic experiments.

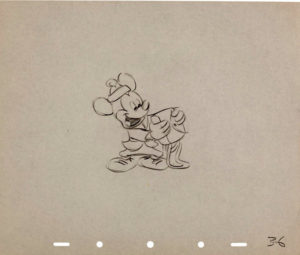

The new Mickey animation in this film is notable in itself: it’s almost entirely the work of Paul Murry, who is remembered today for his work on Disney comic books. Murry had started in the studio’s animation department and had trained under Fred Moore. In Squatter’s Rights, for the only time in his career, he was the lead animator on a Mickey Mouse cartoon short. My colleague David Gerstein has written at length about Murry’s work in comics; for now, suffice it to say that Murry’s distinctive style and poses are on display in most of Mickey’s performance here. It’s also worth noting an exception to this rule: at the climax of the picture—for one scene—Marvin Woodward takes over Mickey’s animation. Woodward was one of the studio’s most experienced Mickey Mouse animators, and the scene in question is a key incident in the story, capturing Mickey in an unaccustomed emotional moment.

SQUATTER’S RIGHTS

2317

7 June 1946 (RKO Radio)

MPPDA certificate 10510

Director: Jack Hannah

Layout: Yale Gracey

Animation: Bob Carlson (chipmunks awaken; chipmunks blow out matches and newspaper; chipmunks give Mickey hotfoot; chipmunks shake hands in closing scene)

Murray McClellan (chipmunk washes face, chipmunks hear approaching sounds and

alarmed at entrance of Mickey and Pluto; chipmunk mimics Pluto and punching-bag gag; chipmunk followed by Pluto’s nose, ducks into milk; chipmunks open catsup)

Paul Murry (Mickey enters cabin, takes off coat; Mickey scolds Pluto; Mickey tries to

start fire in stove; Mickey with hotfoot; Mickey exits cabin; chipmunks shame Pluto; chipmunks hide behind bowl; chipmunks and Pluto jump to mantle; Mickey reenters cabin; Mickey out door with Pluto and runs over horizon)

Hugh Fraser (Pluto enters cabin, brings log to stove and discovers chipmunk; Pluto barks

at chipmunks and reacts to Mickey’s scolding; Pluto brings wood, matches, newspaper, kerosene; Mickey confronts Pluto with match in mouth [with Coe]; Pluto waits for Mickey’s exit and chases chipmunks; Pluto sniffs after chipmunks, looks at milk, sucks milk from bowl; Pluto suspended between gun and table; Pluto lands on floor, doused with catsup)

Hal Ambro (chipmunks hide behind stove leg, imitate Mickey, plant match in Pluto’s mouth; Pluto’s nose jammed in gun barrel)

Al Coe (Mickey confronts Pluto with match in mouth [with Fraser], Pluto swallows match; LS Pluto chases chipmunks around room)

Ken O’Brien (Pluto confronts chipmunk in bowl, chipmunk escapes; chipmunks watch from inside stein)

Marvin Woodward (Mickey sobs with Pluto in arms)

Scenes reused from “The Pointer”:

Norm Ferguson (Pluto rolls over on back, jumps up on Mickey)

Ollie Johnston (Mickey in CU forgives Pluto)

John Lounsbery (Mickey in MS forgives Pluto)

Efx animation: John Reed (gun cocks; toenails slip from table)

Assistant director: Toby Tobelmann

Unit secretary: Mary Satterwhite

Another notable aspect of Squatter’s Rights is immediately obvious: the two mischievous chipmunks, clear prototypes for the little imps who would be developed as Chip and Dale shortly afterward. This was not the chipmunks’ first appearance; they had bedeviled Pluto in the wartime short Private Pluto (1943) and had been proposed for a followup Donald Duck short, eventually abandoned, before making this return appearance in Squatter’s Rights. Here they are animated primarily by Murray McClellan, who had been an assistant in the “animal unit” on Snow White a decade earlier. In 1947 they would turn up again in the “Bongo” segment of Fun and Fancy Free, among the chorus of forest animals mocking the little circus bear when he tried to climb a tree. Later the same year, after a slight redesign, their stardom would be made official in the short Chip ’n’ Dale.

Another notable aspect of Squatter’s Rights is immediately obvious: the two mischievous chipmunks, clear prototypes for the little imps who would be developed as Chip and Dale shortly afterward. This was not the chipmunks’ first appearance; they had bedeviled Pluto in the wartime short Private Pluto (1943) and had been proposed for a followup Donald Duck short, eventually abandoned, before making this return appearance in Squatter’s Rights. Here they are animated primarily by Murray McClellan, who had been an assistant in the “animal unit” on Snow White a decade earlier. In 1947 they would turn up again in the “Bongo” segment of Fun and Fancy Free, among the chorus of forest animals mocking the little circus bear when he tried to climb a tree. Later the same year, after a slight redesign, their stardom would be made official in the short Chip ’n’ Dale.

Squatter’s Rights marked Mickey’s first screen appearance after the war, but it was actually started during the war. Production commenced in the spring of 1944, was temporarily suspended, and resumed in September 1944, proceeding slowly and intermittently through the fall of 1945. By late January 1946 Technicolor photography was completed, and the film was ready for release. Note, in the credit list above, the presence of Eloise “Toby” Tobelmann, one of the unit secretaries at the Disney studio. During the wartime manpower shortage, when women were sometimes moved into jobs ordinarily held by men, Toby served as the assistant director of a handful of Disney films. Squatter’s Rights was one of them.

Finally, it’s worth noting one more anomaly in the history of this unique little cartoon. Like many other Disney cartoons, before and after, this one features appearances by both Mickey and Pluto—but the Mickey Mouse series and the Pluto series were two separate product lines at the studio. Even if both characters appeared in a film, it must finally be branded as a Mickey cartoon or a Pluto cartoon. For bookkeeping purposes at least, it must be identified as an entry in one series or the other. Squatter’s Rights is unusual in that it was inconsistently identified, at one time or another, with both series. (This may be one reason it has sometimes been overlooked in surveys of Mickey’s cartoons.)

Finally, it’s worth noting one more anomaly in the history of this unique little cartoon. Like many other Disney cartoons, before and after, this one features appearances by both Mickey and Pluto—but the Mickey Mouse series and the Pluto series were two separate product lines at the studio. Even if both characters appeared in a film, it must finally be branded as a Mickey cartoon or a Pluto cartoon. For bookkeeping purposes at least, it must be identified as an entry in one series or the other. Squatter’s Rights is unusual in that it was inconsistently identified, at one time or another, with both series. (This may be one reason it has sometimes been overlooked in surveys of Mickey’s cartoons.)

I am indebted to Kevin Kern of the Walt Disney Archives for pursuing the tangled history of this production: as originally conceived, it was registered with the MPPDA in October 1944 as a Pluto cartoon. By the time the main titles were photographed in the camera department, in December 1945, it was officially a Mickey cartoon, and duly opened with the giant Mickey closeup and the words “A Walt Disney Mickey Mouse.” This was the way movie audiences saw it in 1946—after which it was absorbed into the studio’s backlog of films, identified in company records as a Pluto cartoon. The confusion is embedded in the film to this day: as it begins, we see the Mickey Mouse opening titles—while, on the soundtrack, we hear the main-title theme music from the Pluto series!

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

Would this also be the first time Jimmy MacDonald voiced Mickey?

Except for a snippet of Walt as Mickey from “The Pointer” (“Aw, shucks, Pluto. I can’t stay mad at ya.”), it’s clearly Jimmy.

I also noticed that they stopped using the red burlap background on the main titles and replaced it with the “musical notes and staff lines on red” background that they used during the late ’40s- early ’50s, (especially for reissues). When exactly did they stop using the burlap title cards?

Pluto is particularly mean in this cartoon, actually wanting the chipmunks to burn to death. Also, the ending, although no one is actually hurt, is somewhat gruesome for a Mickey/Pluto cartoon. It would be more appropiate for a Donald Duck cartoon. Perhaps it’s because Jack Hannah, who usually directs the Duck cartoons, is directing this one?

Loved Pluto’s wild take where his head splits in three. The Disney animators really could cut loose once in a while and match the Warners animators in wackiness.

Thank you for your thoughts, Tony. “First” is always a problematic word in film history, nowhere more than in the nebulous field of character voices in animation. I hesitate with this one because both Jim Macdonald and Ford Banes recorded Mickey Mouse dialogue much earlier than is usually recognized, sometimes for cartoons that were never completed. (The big case in point is “Mickey and the Beanstalk,” which was started as early as 1938 and progressed, intermittently, and was reworked many times, before it was finally completed and released as part of “Fun and Fancy Free.”) It may well be that “Squatter’s Rights” was the first cartoon *released* with Macdonald’s voice for Mickey. And that’s a good question about the title cards! I’ve never pursued that question with those later cartoons, but now you’ve made me curious about it too.

Ford Banes is my husband’s great uncle! I’ve been trying to find more information about his time and role at Disney bit haven’t had much luck

The special title cards were a special design for reissues such as ‘Little Toot’ from ‘Melody Time’, throughout 1953 to early 1956; sooner or later, newer reissues used went back to using traditional, familiar backgrounds, which lasted right up until the 1970’s reissues.

The ending of the cartoon — where Mickey thinks Pluto’s been shot and rushes the ketchup-smeared dog off to the vet as the proto-Chip and Dale laugh inside the cabin — is both dark & unsatisfying because the story feels so unresolved. Jack Hanna sometimes loved his chipmunks too much, here and in the later Donald series, to where the levels of abuse their adversaries (who are supposed to be the stars of the cartoon) take is over-the-top, to the point you’d like to see the mouse, the dog or even the duck get a little retribution before the iris out.

Couldn’t agree more. This is a big weakness of many later Disney cartoon shorts, and one of the primary reasons why I much prefer Jack King’s Donald Duck cartoons to Jack Hannah’s.

>Squatter’s Rights is unusual in that it was inconsistently identified, at one time or another, with both series.

‘Goofy and Wilbur’ was released as a Silly Symphony? No wait, the reissues say it’s a “Goofy” title?! No wait, the MPPDA copyright entries say it’s a “Mickey Mouse”? These are all three true statements. The publicity stills say that it’s a Silly Symphony, and so do some of the release posters; half of the other posters call it a “Goofy” title. The most bizarre case seems to go with to the copyright entry.

Got any words on that title?

Yes, I’ve got plenty of words about “Goofy and Wilbur,” but that one was a different kind of anomaly. It was made after the studio contracted with RKO Radio for distribution of its cartoons. The previous distribution deals with Columbia and United Artists had called for predetermined numbers of Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony cartoons — leading to occasional oddities like “Mickey Mouse” cartoons in which Mickey did not appear. The RKO contract was much more flexible, requiring only a set number of Disney cartoons, with whatever characters or stories the studio chose. That was when the separate series of Donald Duck, Pluto, and Goofy cartoons got started, and of course the Goofy series started with “Goofy and Wilbur.” Why that short was copyrighted as a Mickey Mouse, or advertised as a Silly Symphony, is open to question, but it may have been simply clerical force of habit after all those years. (Incidentally, the Copyright Office and the MPPDA were two different things.)

Woops! I didn’t mean to include MPPDA as remotely even similar to copyright, but indeed, yes, copyright entries indeed call this a “Mickey Mouse”. It was internally, a Mickey Mouse (prod. 2218), and part of the draft code, and promotional material later shows that this moved to a Silly Symphony (prod. RS8); what’s even more odd is that the promotional material for ‘Beach Picnic’ calls itself a Silly Symphony, yet the images shown have a Mickey Mouse production code; where the Donald, Donald & Goofy and Pluto the Pup cartoons would be tagged as well.

Do you have insight on what RS8 is in your documents?

RS 8 was the original production number for “The Ugly Duckling” (the 1938 version). The studio switched to the new numbering system while the cartoon was in production, and by the time it was completed and released the number had been changed to 2216.

Here’s one of the promotional materials in question ‘Goofy and Wilbur’ is RS8–

https://vignette.wikia.nocookie.net/disney/images/c/c7/1939_Goofy_and_Wilbur_%28ing%29_%28still%29_02.jpg

And a preliminary poster of ‘The Ugly Duckling’ showing an RS8 code as well.

http://auctions.emovieposter.com/Bidding.taf?_function=detail&Auction_uid1=4864350

Oops again, I posted the top image at the wrong size.

https://vignette.wikia.nocookie.net/disney/images/c/c7/1939_Goofy_and_Wilbur_%28ing%29_%28still%29_02.jpg/revision/latest/scale-to-width-down/620?cb=20140401035802

And the drawings on the promotional, not just screenshots of the cels themselves, have the same “RS8” code. It was likely that ‘Goofy and Wilbur’ was RS8 first

https://thumbs.worthpoint.com/wpimages/images/images1/1/0216/17/1_75e9bcdc9214819c8e194c821929333d.jpg

This short looks like a precursor to the short PLUTO’S CHRISTMAS TREE.

I’ve wondered why this was listed as a Pluto short despite the Mickey opening credits. Did the series mixup occur with other Mickey/Pluto shorts? The same inconsistency with the opening titles occurs on LEND A PAW, MICKEY DOWN UNDER, and PLUTO’S PARTY. These and a few other shorts in the Mickey series appear exclusively on the Complete Pluto volumes on the Disney Treasures.

Meanwhile, “Plutopia” is in the Mickey Mouse set despite Pluto’s head and name being in the opening titles.

The listing confusion for this short simply highlights the animators’ struggling to make Mickey a workable character, even though their hearts were clearly set on Pluto. This would occur several times more, where a Pluto story would occasionally get a Mickey Mouse label.

This also precedes what would become an unfortunate regularity in the Donald series: being permanently upstaged by two rodents, to the point where many other aspects of Donald’s life and personality took a backseat.

At least those were way better than a later series with a duck and a rodent.

Well before the war, Mickey put Disney in a weird position: He was wildly popular and beloved, but that very popularity (and an affable, harmless temperament) meant a lot of comedy was off limits to him — especially as Mickey “grew up” from his early kid persona. So the studio used him as a straight man to other characters, and that justified keeping his valuable name and face in front of the public.

In contrast, Mickey successfully held center stage in the newspaper strip and comic books. Perhaps because those media offered space for Mickey to be an active hero or domestic comedian while staying true to his nice guy persona.

Thanks for confirming Paul Murry’s work, JB. A friend seemed beyond convinced Freddie Moore did it years ago. I appreciate your due diligence documenting every little detail you can about these films. Disney should be paying you (and David) to do this full-time!

Thank you, Thad. I’d be open to that idea! Yes, it’s interesting to see the influences of the different animators on Mickey’s appearance. In the earliest years, especially, I don’t think any two artists drew him exactly alike, but even in later films the hands of some artists — like Murry, or Dick Lundy — are apparent.

Your hot link in this leads to an amazon listing for a Floyd Gottfredson collection?

Did Gerstein write about Murry in that book, or was it a mistake? I’d love to read any info I can find as Murry is my favorite Mickey comic book artist.

Yes. David Gerstein writes about Paul Murry in that volume (#8) of the Floyd Gottfredson Library.

Wes, you may be aware of this, but there are also some articles (by Disney aficionados Germund Von Wovern and Joe Torcivia) in the first Paul Murry volume of Fantagraphics’ “Disney Masters” series: https://www.amazon.com/Disney-Masters-Vol-Disneys-Vanishing-ebook/dp/B07892LNG3

Nice stuff on The Mouse by Paul Murry in SQUATTER’S RIGHTS. I wonder if he animated any other Disney shorts before devoting himself to comic books? I liked Bob Carlson’s stuff on the chipmunks, lots of fun and exaggerated acting. Bob Carlson was also the inventor of the “Carlson scramble”, which was used in the Humphery Bear cartoons whenever the hapless bear was under extreme stress and his legs went in all directions.

I wonder why this wasn’t released with on-screen credits? Online sources (including IMDb) have given the [ostensibly credited] animators as Bob Carlson, Murray McClellan, Hugh Fraser and [presumably effects] Blaine Gibson, which seems fairly accurate, so maybe there are prints somewhere, or an entry in a copyright catalogue, which has those names on it?

It’s interesting to know that so much of this cartoon was animated by the perennially uncredited Paul Murry.

The surviving camera negatives were altered on reissue; who knows if the original titles actually had credits.

This was an interesting short. Seeing Paul Murry’s Mickey animation is perhaps the most interesting thing about it. There are too many gags that feel like Disney’s gag men have seen one too many Tom and Jerrys, and are trying to bring this style of humor to their work. While it may be funny to see these things happen to Tom, Pluto is a loveable character and seeing all these awful things happen (like the bits at the end with the gun and the ketchup, and Mickey running out frantically with Pluto) seem less funny because of it. Disney’s characters were personalities, not interchangeable comedians like the MGM and Warner Bros. characters.

I have a copy of a model-sheet to this cartoon (with lots of chipmunks and Mickeys on it) listing Paul Murry as “Mickey keyman” and Ray Medby (!) as “Chipmunk keyman”. Can’t find any info on Medby, but he sure could draw nice chipmunks!