Another book written by me has just been released: Secret Stories of Mickey Mouse: Untold Tales of Walt’s Mouse

Another book written by me has just been released: Secret Stories of Mickey Mouse: Untold Tales of Walt’s Mouse

To celebrate Mickey Mouse’s upcoming 90th anniversary, I compiled over a hundred short stories about him from the New York woman who killed her husband because she thought he was possessed by Mickey Mouse to Mickey rides designed by Ward Kimball for the Disney theme parks that were never built to a chapter devoted to quotes by people like Don Bluth and Ralph Bakshi about Mickey.

Here are a couple of animation related tales that might encourage you to ask Santa to include it as a stocking stuffer this year.

During World War II, the Disney Studio provided hundreds of insignia designs for various branches of the U.S. Armed Services.

While no official numbers were kept, Mickey Mouse appeared on less than three dozen and generally for units like the signal corps, home front activities or a chaplain’s unit. He was just considered too nice a guy to appear aggressive. Donald Duck because of his more feisty personality appeared on almost two hundred insignias.

Unapproved Mickey Mouse insignias were even displayed on Nazi warcraft.

A prominent and feared Mickey Mouse insignia first appeared around 1937 when German flying Ace, Adolf Galland of the Luftwaffe, painted a homemade version of Mickey on all the fighters he flew. A demonic looking Mickey had a cigar in his mouth and held a pistol in one hand and an axe in the other. When asked why he chose Mickey Mouse, Galland replied, “I like Mickey Mouse. I always have. And I like cigars, but I had to give them up after the war.”

Hundreds of German U-boat submarines displayed emblems on their bows during the war. They varied from typical war emblems of swords, axes and torpedoes to even Mickey Mouse with an umbrella on U-26 that served from 1936 to July 1940 and sank eleven ships.

Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini and Emperor Hirohito were all huge Mickey Mouse fans. Hitler had a personal collection in his film library of over two dozen Mickey cartoons by the end of 1937 despite his public attempts to ban the Mouse in Nazi Germany because of the little fellow’s popularity and prominent association with the United States.

Mussolini allowed the Mickey Mouse comic strip to continue in Italian newspapers despite banning all other non-Italian comic strips. Hirohito treasured his Mickey Mouse watch so much that he insisted he be buried with it when he died in 1989.

Today, the Japanese adore all things Disney. They produced tin toys of the characters. They are the home for the first foreign Disney theme park. However, in the dark days of World War II, Mickey was seen as an icon representing everything evil about a capitalistic United States threatening Japan.

It was not just the United States that produced animated cartoons for propaganda purposes. In 1934, Japan released the eight minute Omochabako series dai san wa: Ehon senkya-hyakusanja-rokunen (Toybox Series 3: Picture Book 1936) by Komatsuzawa Hajime. On the internet, it can be found under the title Evil Mickey Attacks Japan.

.

A Japanese island is populated by cute animals and children who sing and dance. One of the animals even resembles a counterfeit Felix the Cat. However, their happiness is short lived because from the air they are attacked by an army of Mickey Mouses, riding horrific bat-like creatures who also have Mickey Mouse heads. These villains are assisted by snapping crocodiles and vicious snakes who act like machine guns.

One of the frightened inhabitants appeals to a huge storybook to summon their folk heroes to protect them. Momotaro (“Peach Boy”), Kintaro (“Golden Boy”), Issun-boshi (“One Inch Boy”) and Benkei, a warrior monk, all answer the call to battle the evil Mickey Mouses. The message was that the classic Japanese folklore characters were much more powerful than this recent cultural upstart.

The film was made in 1934 but was dated 1936 supposedly to coincide with the expiration of a naval treaty between the United States and Japan which would eventually lead to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Through magic, Mickey is defeated and even turned into a decrepit character to humiliate him and who hobbles away to a flood of laughter while the residents return to their joyful lives.

Mickey’s use wasn’t just confined to World War II.

Mickey Mouse in Vietnam was the work of Lee Savage (father of Mythbusters Adam Savage) and Milton Glaser (who designed the I ♥ New York logo) for the Angry Arts Festival in 1968. The festival was designed to give creative artists a forum for protesting the Vietnam War.

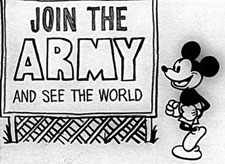

The silent, 16mm black-and-white cartoon that lasts a little over a minute was officially titled Short Subject. It finds the early 1929 version of Mickey Mouse happily walking along. He passes a billboard that reads, “Join the Army and See the World.” Mickey studies the billboard, walks off-screen, and then returns wearing a helmet and carrying a military rifle with a bayonet.

The silent, 16mm black-and-white cartoon that lasts a little over a minute was officially titled Short Subject. It finds the early 1929 version of Mickey Mouse happily walking along. He passes a billboard that reads, “Join the Army and See the World.” Mickey studies the billboard, walks off-screen, and then returns wearing a helmet and carrying a military rifle with a bayonet.

Mickey sails off on a tugboat (so small that he is the only passenger) with the words “To Vietnam” printed along the bow. The voyage is unusually quick, with Mickey sailing across a calm Pacific Ocean from the USA (which is helpfully identified by a large sign posted on its shoreline) to Vietnam (which has its own large sign on its shore, along with huge explosions popping all over its land mass). Mickey arrives and marches into Vietnam, following an arrow-shaped sign that reads, “War Zone”.

Mickey is barely a few seconds into an overgrown jungle when he suddenly drops his rifle, goes stiff and falls over backwards. The camera finds him flat on the ground, with a bullet hole in his skull. Mickey’s smiling face turns glum as blood trickles out of the bullet hole. That’s the entire film.

Savage, who is credited as director and animator of the short, and Glaser offered private screenings during the early 1970s. The film occasionally popped up in film festivals but was not widely known among Disney fans and was never released theatrically.

“Mickey Mouse is a symbol of innocence, and of America, and of success, and of idealism,” Glaser said. “And to have him killed, as a solider is such a contradiction of your expectations. And when you’re dealing with communication, when you contradict expectations, you get a result.”

The Disney Company made no attempt to destroy copies of the film as it was rumored but neither did it give the short film any public recognition. Glaser remembers there was some talk about Disney suing them but he was told it didn’t happen because Disney didn’t want to attract any attention to the film and felt it wouldn’t be able to recover sufficient enough financial penalties to justify the time and expense.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Hi Jim! Talked about you at http://www.afnews.info:

http://www.afnews.info/wordpress/2018/10/27/mickey-mouse-e-con-noi/

🙂

Many thanks…and thanks for the link to my book as well! Loved the other huge photo you found of the Galland insignia.

Lee Savage later did animated segments for “Sesame Street” and “The Electric Company” (Harold! You forgot your lunch!”). For Sesame’s He, She, and It segments (where they explain how things work), nine year old Adam voiced the boy, Heathcliff.