Donald Duck in Close-Up #11

Given the literally hundreds of films and TV programs that featured Donald Duck during Walt Disney’s lifetime, it might seem that every possible screen story idea for the Duck had been exhausted. In fact, however, the Disney story department hatched a vast number of Duck-centric ideas that never did reach the screen. From gags eliminated from a continuity, to story ideas that evolved beyond recognition on their way through the story-development process, to complete films that were planned and sometimes even started production before being abandoned—the story of the unseen Donald is an immense one. My colleague David Gerstein has made something of a specialty of studying these unproduced cartoons, and has made some fascinating discoveries, soon to be published.

In light of that imminent publication, I will not reveal David’s finds before their time. But over the years, in the course of other projects, I’ve stumbled onto a few of those “films that never were” myself.

The story of Donald’s unseen adventures actually begins with his very first film, The Wise Little Hen. Every Disney fan knows this delightful Silly Symphony, and Donald’s debut performance in it. Less well known, perhaps, is that some of his performance was cut from the final version of the film. His introductory scene, dancing a hornpipe on the deck of his houseboat, was animated by none other than Art Babbitt and originally ran much longer than the dance we see in the finished film. A more substantial cut was made in the closing sequence, when the hen responded to Donald’s and Peter Pig’s faked “bellyaches” with the gift of a bottle of castor oil. As animated by Dick Huemer, the Duck and Pig engaged in an elaborate Alphonse & Gaston routine, passing the bottle back and forth with exaggerated politeness before proceeding to the final scene. These scenes were not only animated, but inked, painted, and photographed in Technicolor before being eliminated from the final cut. They have survived in a silent color workprint, saved by the estimable Mark Kausler and preserved today in the Academy Archive.

The story of Donald’s unseen adventures actually begins with his very first film, The Wise Little Hen. Every Disney fan knows this delightful Silly Symphony, and Donald’s debut performance in it. Less well known, perhaps, is that some of his performance was cut from the final version of the film. His introductory scene, dancing a hornpipe on the deck of his houseboat, was animated by none other than Art Babbitt and originally ran much longer than the dance we see in the finished film. A more substantial cut was made in the closing sequence, when the hen responded to Donald’s and Peter Pig’s faked “bellyaches” with the gift of a bottle of castor oil. As animated by Dick Huemer, the Duck and Pig engaged in an elaborate Alphonse & Gaston routine, passing the bottle back and forth with exaggerated politeness before proceeding to the final scene. These scenes were not only animated, but inked, painted, and photographed in Technicolor before being eliminated from the final cut. They have survived in a silent color workprint, saved by the estimable Mark Kausler and preserved today in the Academy Archive.

That was only the beginning. As Donald continued to appear in new films and was established as a popular character, his colorful personality suggested so many story possibilities that some of them inevitably fell by the wayside. (A particularly striking gag from Donald’s Ostrich—once again, inked and painted and filmed in Technicolor before being cut—has been located by British film collector Erik Palm, and some of its history will be unveiled in the near future.)

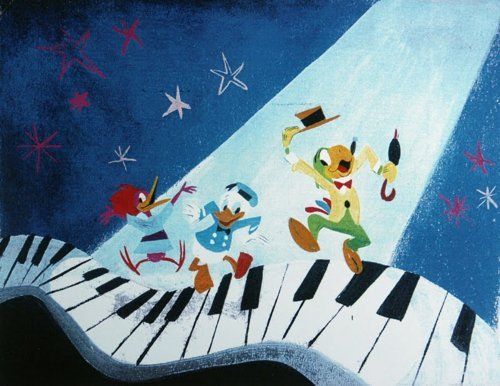

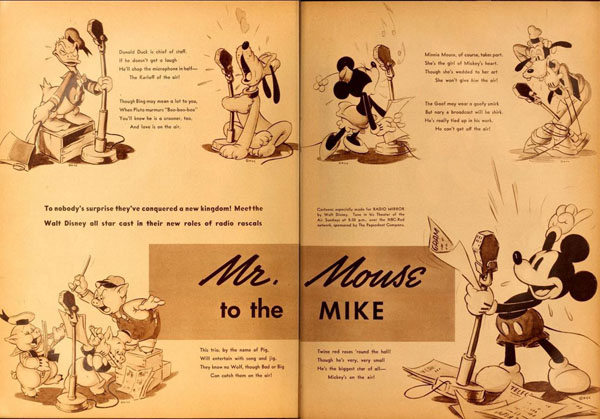

Inspiration for new story ideas could be found anywhere. When the Disney radio program Mickey Mouse Theatre of the Air was launched in January 1938, featuring Mickey and other assorted Disney characters, Donald was a prominent member of the cast. The third episode of the show introduced a novelty gadget band, led by Donald, that played mangled musical selections with plenty of sound effects. Behind the scenes, the ensemble was augmented by Hal Rees and other members of the Disney sound-effects crew. Their performance made an impression that lingered after the broadcast ended. In succeeding months “Donald Duck and His Webfoot Band” would return to the Disney radio program, and were also invited (i.e. Rees and his colleagues, along with Clarence Nash) to give live performances at public functions. Inevitably, they also provided the inspiration for a Disney cartoon short. “Donald’s Webfoot Sextette” was to feature an impromptu battle between the group of the title and Mickey’s legitimate classical orchestra. The film was never completed, although Symphony Hour (1942)—in which Mickey’s orchestra (including Donald) tries to play von Suppé’s “Light Cavalry Overture” on instruments that have been flattened in an elevator shaft—reflects something of the same spirit.

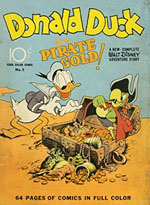

One of Donald’s unfinished films has actually become celebrated among Disney fans, thanks to an unconventional turn of events. In the late 1930s and early ’40s, the studio developed several potential stories for feature-length films in which Donald would appear with his frequent costars Mickey and Goofy. Only one of those stories was ever completed: Mickey and the Beanstalk, which ultimately was released as a segment in Fun and Fancy Free. One of the unfinished Mickey-Donald-Goofy ideas was “Morgan’s Ghost,” a pirate story that owed more than a little to Treasure Island. The story was never completed as a film—but in 1942 it was adapted as a comic book, Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold, featuring Donald and his three nephews. This comic book would find an important place in Disney history, for it was drawn in its entirety by Duck veterans Jack Hannah and Carl Barks. Barks had been employed at the studio for seven years, but in 1942 he was on the verge of departing to work on his own. Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold marked his pivot to what would become a legendary career as a comic book artist. In the end, “Morgan’s Ghost” was one unfinished Donald picture that actually became a Donald milestone.

One of Donald’s unfinished films has actually become celebrated among Disney fans, thanks to an unconventional turn of events. In the late 1930s and early ’40s, the studio developed several potential stories for feature-length films in which Donald would appear with his frequent costars Mickey and Goofy. Only one of those stories was ever completed: Mickey and the Beanstalk, which ultimately was released as a segment in Fun and Fancy Free. One of the unfinished Mickey-Donald-Goofy ideas was “Morgan’s Ghost,” a pirate story that owed more than a little to Treasure Island. The story was never completed as a film—but in 1942 it was adapted as a comic book, Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold, featuring Donald and his three nephews. This comic book would find an important place in Disney history, for it was drawn in its entirety by Duck veterans Jack Hannah and Carl Barks. Barks had been employed at the studio for seven years, but in 1942 he was on the verge of departing to work on his own. Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold marked his pivot to what would become a legendary career as a comic book artist. In the end, “Morgan’s Ghost” was one unfinished Donald picture that actually became a Donald milestone.

Some years ago, while researching a book on the Disney studio’s part in the U.S. Good Neighbor program during World War II, I had the opportunity to learn about a number of Donald Duck cartoons with a Latin American theme—some produced and released, others never completed. One of the abandoned ideas was “Caxangá.” This was based on a parlor game, involving matchboxes, that El Grupo had observed in Brazil during their 1941 South American tour. In this game, two or more players would sit at a table and pass a matchbox from one player to the next, using an elaborate pattern of moves, to the rhythm of a catchy song. The tempo of the music increased gradually as the game proceeded, and the game became a test of the players’ dexterity. A game like this suggested rich story material for Donald, who would easily become frustrated and lose his temper.

The Disney writers went to work with this idea as early as October 1941, after their return from South America. Here again, they came up with several different versions of a story. In one, Donald and Joe Carioca were both smitten with a girl they had just met. (An animated girl, that is; combination scenes mixing Donald with live-action performers like Aurora Miranda were still in the future at this point.) As they competed for her attention, she suggested that they could play a game of caxangá, and the winner would dance with her. Once the game started, of course, Donald was no match for Joe. In an alternate scenario, Donald was so frustrated after losing a game of caxangá with Joe and Goofy that he dreamed about it that night. In his dream he was surrounded by matchboxes, pursued by matchboxes, and all to the insistent rhythm of “Escravos de Jó,” the song that accompanied the game.

Both these ideas were developed in turn, and both proceeded to the brink of production, even to the extent of some rough preliminary animation:

Even after both stories were abandoned, the idea of producing some kind of short based on “Caxangá” persisted as late as 1944. In the end, however, blessed with a rich surplus of South American story ideas, the studio never did fully realize this one. The song, “Escravos de Jó,” was heard briefly on the soundtrack of Saludos Amigos, and a live-action demonstration of the matchbox game was glimpsed in the nontheatrical short South of the Border with Disney, but that was as close as the Disney studio came to producing a “Caxangá” film.

Shortly after this idea was abandoned, the studio tackled another Brazilian song. The up-tempo “Apanhei-te cavaquinho,” by Ernesto Nazareth, came to supervising director Norm Ferguson’s attention in 1945, and he wrote enthusiastically to Walt that “it has the possibilities of ‘Tico Tico.’” Ferguson had this number in mind for what was planned as a third Latin American feature, to follow Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros. That third feature was never completed, but ultimately “Cavaquinho” reached the screen as “Blame It on the Samba,” a segment in Melody Time (1948). Along the way the story went through another long evolutionary process, and some intriguing ideas were developed before being dropped.

Walt Disney with Brazilian billionaire playboy Jorge Guinle and Carmen Miranda in 1943

One of the most fascinating involved the “Brazilian Bombshell” herself, Carmen Miranda. During production of The Three Caballeros the studio had plunged into the making of elaborate combination scenes, picturing animated characters on the screen alongside human performers filmed in live action. One of the performers in question was Aurora Miranda, Carmen’s sister, for whose attentions Donald and Joe Carioca frantically competed. Now, for a followup production, the writers depicted Donald setting his romantic sights on Carmen, a hugely popular international star at the time.

In this version, Donald and Joe were pictured visiting a nightclub where both Carmen Miranda and organist Ethel Smith were performing. (By March 1945 Smith had already recorded an organ performance of “Cavaquinho” for the studio and, with the addition of a new English lyric by Ray Gilbert, the song had been rechristened “Blame It on the Samba.”) Visiting Carmen in her dressing room, Donald was captivated by her charms. A kiss from Carmen before she went onstage to perform, and Joe’s romantic tales of Rio while the song was heard offscreen, propelled Donald into a euphoria of colorful fantasy images. This premise inspired the artists to come up with ever more delirious imagery as story development proceeded. At one point the crazy Aracuan from Three Caballeros made a return appearance, making a huge black-and-white drawing of Rio, then filling in the colors by poking rain clouds with a paintbrush and causing colors to rain down on the city.

Concept Painting by Mary Blair

Eventually, of course, almost all of these ideas were dropped. Carmen Miranda did not appear in the film (though the Aracuan did), Ethel Smith’s role was greatly expanded, and Donald and Joe focused their attention on her in a completely revised storyline. But today’s Disney fans are unlikely to complain. Blame It on the Samba in its finished version remains a cult favorite which has been written about elsewhere, most recently by our own Jerry Beck here on Cartoon Research. It’s one more illustration of the volatile richness of Donald Duck’s character, which inspired such a wealth of story ideas that only a fraction of them could be fully realized on the screen.

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

A cavaquinho is a kind of small guitar with four strings. Portuguese traders brought them to the Hawaiian Islands, where the instrument was developed into the ukulele.

Are there any extant audio recordings of Donald’s gadget band from the Mickey Mouse radio show?

Some fascinating pieces of history here, particularly that ‘Caxanga’ short. With so many uncompleted films in the Disney history, it would be interesting if Disney made a program to complete them for aspiring animators and storypeople.

There could even be differing levels of complexity, from scenes and shorts that reached the animation stage before being abandoned, to those that didn’t get past storyboard, to finally those ideas that only existed in concept art.

I have a copy of the book “Treasures of Disney Animation Art” which has story sketches for an unfinished cartoon “Donald Catches a Cold”. Donald shows off how water just slides off a duck’s back and ends up catching a cold.

A Jose’ plush doll! I died!!!!

Interesting. Some of this music ended up in the cartoon “Springtime for Pluto” in 1944 with Thurl Ravenscroft singing a portion of that catchy little number. It was also heard in the Pluto, “Pluto’s Blue Note” from 1947.

I hope to see that missing Donald Duck animation from “Wise Little Hen” someday. That would be a treat.

Interesting but I can see why that short was never finished. It looks like some of the gags made it into “Drip Dippy Donald” (1948).

Now how do I get that song out of my head??

I have nothing against being called British, but I’m really born and raised here in Sweden. 🙂

The one thing I would really like to see some day, if it still exists, is the pencil tests for “Share and Share Alike,” a complete 1946 Donald short that went all the way to finished animation before it was abandoned.

Several years ago, I contacted the daughter of Gordon “Felix” Mills – Betsy Goodspeed – about her father’s compositions for the 1930s radio show, CHANDU THE MAGICIAN in the early 1930’s. She knew nothing at all about the work her dad did orchestrating the composer’s piano scores for THE CINNAMON BEAR (c. 1937), but she did remember hearing that her dad was hired to work on MICKEY MOUSE THEATRE OF THE AIR. I’ve heard that some of these broadcasts were discovered some years ago. Can you give me a little history of the radio program and how many episodes were completed? Thanks!