Suspended Animation #323

Last week, I started talking about the Disney parodies that Bob Clampett made while at Warner Brothers.

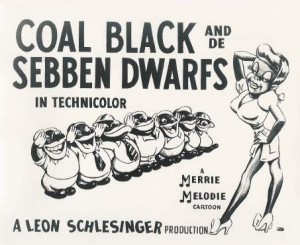

Clampett was responsible for the very much still-controversial cartoon short, Coal Black and De Sebben Dwarfs (1943). It is a modern parody retelling of the Disney version of the timeless classic of Snow White but with black caricatures.

Clampett was responsible for the very much still-controversial cartoon short, Coal Black and De Sebben Dwarfs (1943). It is a modern parody retelling of the Disney version of the timeless classic of Snow White but with black caricatures.

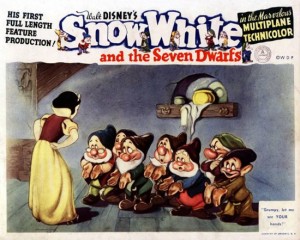

So White and the Prince Chawming see their reflection together in the water the same as the Prince and Snow White in the original. The wicked queen observes them through pulled curtains just like in the original. The heroine wanders through a dark-bluish forest where even the trees appear to have eyes just like in the original.

The wicked queen who is hoarding vital war rations sends the seven dwarfs who are a Murder Inc. gang to murder “So White” (aka “Coal Black”), but the dwarfs are charmed by the young girl and join the U.S. Army instead. When Prince Chawmin’s kiss can’t awake her after she eats a poisonous caramel apple on a stick, it is Dopey’s all-American pucker that makes her pigtails stand up, unfurling into small American flags.

The real origins of this classic cartoon parody came from Clampett’s studying the caricatures in the book, Harlem As Seen by Hirschfeld by artist Al Hirschfeld. In addition, Clampett attended Duke Ellington’s 1941 live musical revue being performed in in the Los Angeles area, Jump for Joy.

The real origins of this classic cartoon parody came from Clampett’s studying the caricatures in the book, Harlem As Seen by Hirschfeld by artist Al Hirschfeld. In addition, Clampett attended Duke Ellington’s 1941 live musical revue being performed in in the Los Angeles area, Jump for Joy.

After the show, Ellington and the cast suggested Clampett make a musical cartoon that focused on “black” music. To prepare for this project, Clampett had his animation unit take a couple of field trips to Club Alabam, a Los Angeles area nightclub that catered to black Americans.

At the time, people were talking about Carmen Jones, a black version of the famous Carmen opera and that might also have inspired Clampett.

Animator Virgil Ross in an interview with John Province in 1990 recalled, “Bob (Clampett) took us into downtown Los Angeles, into the nightclub section, to watch the latest dances and pick up some atmosphere. Some of it was pretty funny stuff that we actually used in the picture: real tall guys dancing with real short little women, and they’d swing their legs right over the tops of their heads!”

With the hope that having just the right voices for his characters might give Coal Black some additional authenticity, Bob even hired African American actors to perform the lead roles in his film.

With the hope that having just the right voices for his characters might give Coal Black some additional authenticity, Bob even hired African American actors to perform the lead roles in his film.

Clampett hired Vivian Dandridge,the sister of black American actress and singer Dorothy Dandridge to voice “So White” and then hired Ruby Dandridge, Dorothy and Vivian’s mother, to voice the wicked Queen.

Bob recruited Lou “Zoot” Watson to do the voice of “Prince Chawmin” while Mel Blanc provided all of the other voices in the picture. Band leader Louis Armstrong wanted to do the voice of Prince Chawmin’ but was booked on tour.

Many animation fans have wondered why this Bob Clampett cartoon is called Coal Black and the Sebben Dwarfs if the main character in the picture is referred to as “So White”? Well, producer Schlesinger feared that calling the cartoon “So White” would be just too close to the title of the Disney original and could cause problems which is why a change was eventually made in the cartoon’s title but not in the cartoon itself where the heroine is called by her original name.

Animation is an exaggerated reality, especially in the world of Bob Clampett. And so the characters in the film were just as exaggerated and stereotyped as any other Clampett cartoon character. However, especially in today’s society those stereotypes that were so common in live action films and on the stage are no longer considered appropriately funny but demeaning, something that was never Clampett’s intent.

Clampett felt restricted by animation and the studio system so he explored his other childhood interest: puppetry.

He created a very popular children’s puppet show entitled Time for Beany in 1949. Comedian Groucho Marx was a huge fan as was scientist Albert Einstein.

In an interview with animation historians Milt Gray and Michael Barrier, Bob Clampett revealed a very special encounter with Walt Disney himself when the puppet show was at its peak:

In an interview with animation historians Milt Gray and Michael Barrier, Bob Clampett revealed a very special encounter with Walt Disney himself when the puppet show was at its peak:

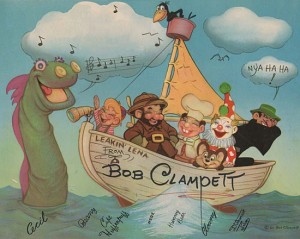

“I was good friends with Walt’s niece, Margie Davis. She invited Uncle Walt and me to one of his grandnephews’ birthday parties. I brought a basketful of Beany and Cecil toys and merchandise. And Walt walked in with an armful of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck toys.

“It so happened that Walt’s own grandnephews were such great fans of my Beany and Cecil TV show that they ran around all day wearing Beany caps, playing with Beany balloons and games, with Cecil and Dishonest John puppets on their arms, giving the D.J. laugh, ‘Nya ha ha!’

“Well, Walt’s eyebrow went sky high. But, of course, it was no time at all until he went on the air with his Mickey Mouse Club and wonderful Disneyland TV program. And I’m sure that his grandnephews thereafter wore nothing but Mousekeeteer caps.”

On the 1962 animated version of Beany and Cecil, Clampett decided to parody the popular “Disneyland” television program in an episode entitled Beanyland.

Clampett’s original pun-filled story was later adapted for the April-June 1963 DELL Beany & Cecil comic book, which was illustrated by Willie Ito, an artist who worked for Disney Feature Animation back in the 1950s.

Clampett’s original pun-filled story was later adapted for the April-June 1963 DELL Beany & Cecil comic book, which was illustrated by Willie Ito, an artist who worked for Disney Feature Animation back in the 1950s.

In the comic book version of this episode, there is a much more detailed map of “Beanyland.” And it features a “Rock and Roller Coaster” and a “Go-Man Chinese Theater” decades before Disney actually built those attractions in Florida.

The story premise for the animated cartoon was that Beany and Cecil were going to the moon to create a perfect theme park with a “20,000 Leaks Under the Sea” ride, a Matterhorn, a train ride and much more.

Their constant nemesis, Dishonest John was already on the moon in hopes of making a fortune shipping the moon’s cheese back to Earth. Of course, wherever there is cheese, there will be mice, who are the residents of the moon.

When I interviewed him, Bob remembered:

“ABC got very upset about ‘Beanyland’ because of course, they had been running the ‘Disneyland’ television program and other Disney programs and they didn’t want to make Walt mad because there were some legal things going on where Disney was leaving ABC. ‘Oh, you can’t have a caricature of Walt Disney in there saying, ‘I’ll make this my Dismal Land’!’

“I’d answer, ‘Where’s Walt Disney in there? The character with the hook nose and mustache is my long time villain Dishonest John. Everybody knows who he is.’ My original version of “Beanyland” was very, very funny because it was such a tongue-in-cheek satire on Disneyland even as to the way they worded their advertising.

“Beany would say stuff like ‘Look, what he’s doing to my creamy, dreamy Beanyland!’ and that made fun of those peanut butter commercials that sponsored Walt’s show.

“I had Dishonest John packaging the moon as cheese and bringing it back to Earth to sell it. On the package, I had the word ‘Krafty’ and ABC was afraid the Kraft Cheese Company would sue them.

“It was those kinds of things they censored and so much more for seemingly no reason. As Captain Huffenpuff said about Beanyland: ‘This place wasn’t built by a mouse; it was built for mice!'”

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

“But, of course, it was no time at all until he went on the air with his Mickey Mouse Club and wonderful Disneyland TV program. And I’m sure that his grandnephews thereafter wore nothing but Mouseketeer caps.”

Clampett seems to be suggesting that Disney was inspired to air those programs by the popularity of the Beany and Cecil gifts among Walt’s grandnephews, but the chronology doesn’t bear this out. The first Beany and Cecil cartoon was broadcast in 1959, while Disneyland premiered in 1954 and the Mickey Mouse Club in 1955, the same year that Lillian Disney’s niece Margie Sewell married WED Imagineer Marvin Davis (not to be confused with WED Imagineer Marc Davis). By the time that birthday party took place, Mouseketeer caps would have been as passé as Davy Crockett coonskin caps.

I’d like to know what Walt Disney’s impressions of Bob Clampett were. But I don’t suppose they were ever recorded.

Actually, Bob was referring not to the cartoon show but the puppet show that aired before the Mickey Mouse Club.

But Jim, according to one of your own articles profiling Marvin Davis, he and Margie were married in 1955. Are you saying that their children were born years earlier, out of wedlock? Or did you get the date wrong? Or is it possible that Bob Clampett made a mistake or stretched the truth just a little bit?

Yes, Margie and Marvin got married in 1955. However, Bob just says it was Walt’s grandnephews. He didn’t indicate it was Margie’s kids, just that she was the hostess. Thanks for trying to keep me honest. Nobody can know everything so I appreciate readers at this site making corrections and additions so that everything is as accurate as possible.

Glossing over the fact that hosting children’s birthday parties is something that single women seldom do, we’re left with the question of who, if not Margie’s son, the birthday grandnephew might have been. Margie Sewell Davis was an only child and had no immediate nieces or nephews. It’s conceivable that the party might have been for one of the children of her cousin Phyllis Bounds, who were all born between 1945 and 1948 and therefore in the prime “Time for Beany” demographic. Since Margie knew Clampett, Phyllis might have asked her to invite him to the party because her kids were fans of his show. Still, in the interview he referred to Margie by her married surname and to his show as “Beany and Cecil” rather than “Time for Beany”, so either Clampett misspoke or was mixed up about something.

Phyllis Bounds’s children would be in their seventies now, but it might be worth asking them if Bob Clampett was ever at one of their birthday parties. I’m sure they’d remember if he had been.

‘He created a very popular children’s puppet show entitled Time for Beany in 1949. Comedian Groucho Marx was a huge fan as was scientist Albert Einstein’.

Whilst Clampett was a bit notorious for his hyperbole, at very least his timeline for this story is correct – as mentioned in the above post, Time for Beany first aired as a puppet-show in 1949. That live-action version of the show ran until 1955, and had a quite a bit of merchandise spun off from it, well before it’s animated incarnation.

Wasn’t it HARPO Marx who was a dedicated fan of “Time For Beany” on KTLA Channel 5 in the late 1940s and early 1950s? His son Bill Marx recalled this incident in a documentary on the Marx Brothers that’s on the Silver Screen Collection.

Great post, but Hammerstein’s “Carmen Jones” didn’t premiere until late 1943; “Coal Black” opened in January of ’43.

Perhaps it was “The Hot Mikado” — a hit all-black staging of Gilbert & Sullivan’s operetta with Bill Robinson, which played both Broadway and the 1939-40 New York’s World’s Fair — which influenced Clampett.

I think I’ve asked this before; don’t remember seeing an answer. Why are there two versions of “Beanyland”?

I’ve always wondered why a few of the Coal Black prints that are floating around on the internet have no green colors. Pretty sure the one included on the Thunderbean special “banned” set is like that.

The dailymotion link above seems to have all colors, just low resolution.

There is another famous anecdote about “Coal Black” that you have recounted at least twice before on Cartoon Research but didn’t mention in the above post. In your Animation Anecdotes #186, you said that Clampett originally told it to historian Reg Hartt in the 1970s, and it has circulated widely since then. As the story goes, the Black Panthers succeeded in having “Coal Black” removed from a screening of Clampett’s cartoons in Los Angeles, and then later that day met with Mayor Tom Bradley. Quoting from your Animation Anecdotes column of May 20, 2017: “When they said they had spent the day at a screening of Bob Clampett cartoons, Bradley responded that Clampett was responsible for his very favorite cartoon of all time, but he had only seen [it] once while in France during World War II: ‘Coal Black and De Sebben Dwarfs’.”

However, Bradley could not possibly have seen that cartoon in France during the war for the simple reason that he was never there. Bradley joined the Los Angeles Police Department in 1940 and married the following year. When the U.S. entered the war, he volunteered for the Army Air Corps and the Coast Guard but was turned down by both. He received an induction notice in 1942, but the head of the local draft board had heard about Bradley’s work in the Juvenile Division during the Zoot Suit riots and, since Bradley’s wife was pregnant with their first child by then, he was granted an exemption from military service. (Source: a 1978 interview with Bradley by Bernard Galm, Department of Special Collections, UCLA Library, posted 2009 by the Online Archive of California. Nowhere in the 281-page transcript of that interview does Bradley mention either Bob Clampett of “Coal Black”.)

I am very sceptical of the claim that Mayor Bradley’s favourite cartoon was “Coal Black”, because it rests upon Clampett’s own account of a meeting at which he was not present. The message seems to be that the Black Panthers, those dangerous radicals, hated “Coal Black”, while Tom Bradley, one of the “good ones”, loved it. If it’s true, then unless Clampett heard it from Bradley himself (doubtful) or one of the Black Panthers (equally doubtful) or through second-hand gossip (unreliable), then he could only have heard about it through some media report, which in principle can be substantiated. Personally it makes no difference to me whether Bradley liked “Coal Black” or didn’t; but since the anecdote nearly always seems to be cited with an agenda in mind — that is, to dismiss the legitimate objections of African-Americans to the stereotypes depicted in the cartoon — I think it requires independent verification before I can accept it without a big dose of salt. As a certain “Wade Sampson” wisely wrote: “One of my best bosses in the entire world taught me to always have at least three independent sources to verify a piece of information. That is a lot harder than it sounds.”

I want to touch on the matter of the dice in Prince Chawmin’s front teeth. Milt Gray, cited in the above article, considers “Coal Black” the greatest cartoon ever made and has defended that gag on the grounds that such dental decorations are, if not widespread, then certainly not unknown among African-American men. He supports this contention with little more than an admittedly vague memory of an advertisement he saw in the 1970s. However, I believe that the prince’s designer incisors were inspired by a specific individual and incident rather than a general fashion phenomenon.

Jazz composer Jelly Roll Morton was in many respects the living embodiment of the flashy urban dandy stereotype epitomised by Prince Chawmin’ — a flamboyant braggart who boasted of having 150 suits in his closet and who had, not a pair of dice, but a half-carat diamond mounted in one of his front teeth. By the 1930s his career had declined to the point that he took a job playing piano in a nightclub in Washington D.C., where he also had to tend bar and serve as bouncer. In 1938 he was stabbed by a patron at the club. He was taken to the nearest hospital, which refused to admit him because it was for Whites Only; and by the time he reached another facility father away, the delay in receiving treatment created complications that affected his health for the rest of his life. At his wife’s urging they moved to Los Angeles in 1940 because of the favourable climate and better access to health care, and also in the hope of reviving his career. Nevertheless he passed away the following year at the age of 50.

The diamond was stolen from Morton’s tooth post mortem, presumably by someone connected with the funeral home. The gem was never recovered, and no one was ever changed with the theft. The story got into the news and became the sort of thing that many people in Los Angeles would have joked about. Certainly it’s not difficult to imagine Clampett doing so at this time, while “Coal Black” was being made; after all, he was a cartoonist, and making jokes was his stock in trade.

The image of the dice played off the stereotypical African-American obsession with shooting craps that by 1943 had been used in countless minstrel shows, hundreds of “coon songs”, and numerous animated cartoons. Bugs Bunny used a pair of dice to confound the hunter in “All This and Rabbit Stew”, the natives of “Betty Boop’s Bamboo Isle” had dice emblazoned on their shields, and “Pair-O-Dice” was written over the gates of heaven in “Clean Pastures”. The dice in Prince Charmin’s teeth were a well-worn cliché that did not mock Morton’s vanity — a universal human foible — but his race, and nothing more.

Today it would be considered hitting below the belt to mock the race of a man whose life, despite his fame and celebrity, had been cut short because his rights could be violated with impunity. But that’s how things were in 1943, and for a long time before that.