Suspended Animation #341

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s 1943 The Little Prince novella has been translated from the original French into more than 250 languages and continues to sell almost two million copies every year. It has inspired films, sequels, a Japanese museum, an opera, a ballet and more. The deceptively simple story is about a pilot who meets a child from another planet.

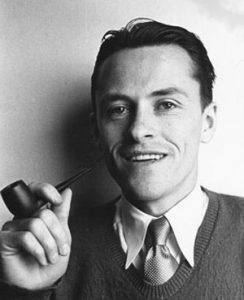

Orson Welles in 1943

After problems with making the Latin American documentary It’s All True, Welles decided that his third film would be The Little Prince where he would portray the aviator and do the narration. He had already started auditioning child actors to play the title role.

Supposedly, when he got a copy of the manuscript, he stayed up half the night reading the story and bought the film rights the next day. Over the decades, he wrote five different screenplays, each averaging about fifty pages, and they all still exist in the Lilly Library.

He wanted to make a hybrid film of live action and animation with him and a young boy in live action but the backgrounds and other effects done in animation.

In 1943, that concept meant going to the premiere animation studio that had great success with animated feature films, the Walt Disney Studio.

According to Welles, he needed animation “to show the tricks of getting from planet to planet” and “The people that (the title character) saw weren’t going to be drawn. They were going to be real comedians. Joe E. Brown was going to be the drunk and so on. There weren’t going to be cute cartoon people on those scenes. But the special effects, which are now in a regular way used as scenery by science-fiction people, were going to be drawn.”

Jackson Leighter was a new business partner of Welles. Having been with the Office of Inter-American Affairs, he knew Walt Disney who had also been recruited by Nelson Rockefeller, the co-ordinator, to make a good will tour of South America that resulted in the film Saludos Amigos (1942).

Jackson Leighter was a new business partner of Welles. Having been with the Office of Inter-American Affairs, he knew Walt Disney who had also been recruited by Nelson Rockefeller, the co-ordinator, to make a good will tour of South America that resulted in the film Saludos Amigos (1942).

Of course, Welles was not interested in working with Walt Disney himself. He has been quoted as saying that “(Walt Disney) had such horrible taste and was so ineradicably German that I just couldn’t bear it. He was very right wing. For Rockefeller who was worried that he was being thought of as too much of an Eastern liberal, Disney was a welcome sunbelt neo-Fascist. Rockefeller was planning on running for president so that made him look good.”

At one point, he discussed with RKO and wrote to Rockefeller about releasing a double bill of his still unfinished It’s All True with Saludos Amigos since they covered similar territory including the Carnival in Rio and the samba. He was greatly disappointed when Saludo Amigos was released seperately and became a huge hit.

But Welles was very interested in working with the Disney animators. He admired their work and considered them true artists.

A lunch meeting was arranged at the Disney Studios in Burbank, California. Welles sat at one end of a long table and Walt sat at the other end. Between the two men were Leighter and the Disney animators.

A lunch meeting was arranged at the Disney Studios in Burbank, California. Welles sat at one end of a long table and Walt sat at the other end. Between the two men were Leighter and the Disney animators.

Once Welles began to speak, he was completely captivating. All heads turned to him as he explained the film with his seductive storytelling. As Welles was creating these word pictures, a member of the Disney staff tapped Walt on the shoulder to inform him he needed to take an important call in an adjoining room.

After Walt left, the same person tapped Leighter on the shoulder that he was also needed on another important call. When Leighter left the room, he found neither he nor Walt were wanted on the phone. Walt had given a discreet signal to the staff member to pretend Walt was needed on a phone call so he could leave the room.

Walt was fuming and Leighter described it as “shaking with rage”. Walt did not hesitate. He was angry that Welles had usurped the attention of his animators who always focused their attention on Walt and his reactions. Walt exploded at Leighter, “Jack, there is not room on this lot for two geniuses!”

Published in 1995 (85p.) this Italian book contains an Italian translation of Welles “The Little Prince” screenplay

However, in 1941 Hugh Harman who had previously worked on Disney short cartoons had started his own studio with Mel Shaw in Beverly Hills at the old Ub Iwerks studio and was interested in doing a feature film especially one about the legend of King Arthur. Harman did eventually work on a film that included King Arthur that was part of an educational short made in the early 1960s for Coronet.

In 1943, Welles made an arrangement with Harman and they were to be co-producers. Welles showed up daily for several months at Harman’s studio where artist Mel Shaw designed a complete color storyboard for the film.

Harman believed he had the financing and distribution set up because of the involvement of Welles but Welles got ill in 1943 and almost died.

Welles flew to New York for work on his radio show and live “Wonder Show” performances but his back problem and jaundice resulted in his being sent to Florida to recuperate. During this time, many of Welles’ proposed projects simply died including The Little Prince.

In July 1947, Harman told the trade papers: “I also have releasing deal with UA, and currently are busy on The Little Prince.”

The first page of Welles script for “The Little Prince”

In 1973, animation author and historian Michael Barrier along with Mark Kausler and Bob Clampett interviewed Harman.

Hugh Harman

“I had occasion to work with him for quite a few months at our studio. He and I went into partnership on a deal to make The Little Prince in 1943, ’44. I developed the greatest respect and regard for that guy; he wasn’t, as the film business had him, a temperamental type; he wasn’t that way at all.

‘He was going to play the lead in it, the aviator, and we were going to get a boy for The Little Prince. Our sets would have been a combination of drawn and live. There would have been animated characters within the scope of the picture playing with these live people.

“We studied and studied and studied that book. We didn’t take it in its transparency; we took it for its deeper meanings. We read Wind, Sand and Stars, another one of the author’s creations (it’s a thing of such magnificent beauty) and after reading that I thought I knew what The Little Prince was about. It is juvenile fiction, and yet there is a depth to it that is amazing.

“We had it all set and were ready to go when Orson became tremendously ill. We couldn’t say a word about it, but he nearly died. He had a bad liver at the time; he went to Florida to recover and was gone for months. We didn’t revive it after that and we lost the whole deal.”

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

What an incredible story! Imagine if, while Harmon was at MGM, he could have actually done this kind of a story in a full length cartoon feature. It certainly would’ve put the MGM cartoon department on the map! I think they could’ve handled it quite well.

Well, this boggles the mind. A feature film of THE LITTLE PRINCE directed by Orson Welles with animation by either Walt Disney or Hugh Harman is far beyond anything I could ever imagine in my wildest dreams. I’m astonished that Welles would even attempt such a project, let alone that it proceeded as far as it did. For all his great gifts, Welles certainly had a lot of bad luck in his life, and one can only wonder what might have been had he not fallen seriously ill at a critical juncture.

On a remotely related subject, I’ve long been curious about the animation in a film that Welles did complete. There’s a scene in “Citizen Kane” that takes place at an outdoor party in Florida, and in the background are animated silhouettes of flying birds — ibises, egrets and the like — giving the setting an exotic flavour. Does anyone know who provided the animation for that scene? It’s pretty basic, but I find it very effective.

Some believe that the bird animation in the KANE Florida party scene was borrowed from RKO’s SON OF KONG.

No, the bird silhouettes in “Son of Kong” are seagulls wheeling against a clear sky. The ones in “Citizen Kane” move more deliberately and in straight horizontal lines.

Great post! Do the storyboards still exist? What a treat it would be to see them! And to see the different scripts!

Great research on this, Jim!

You’d think that after all the borrowing from Disney for CITIZEN KANE, the great Orson would be a little more inclined to work with “Uncle Walt.” But, yeah, two “geniuses” working together would have been a real “Battle of the Titans”!

What a painful “might-have-been”!

Some stories are unfilmable, particularly fantasies which come to life better–and not uniformly–in people’s heads than on a screen. There’s never been and probably never will be a wholly satisfactory “Alice in Wonderland.” “The Wizard of Oz,” which was hated by most critics on its initial release, became a classic because of the ritual annual TV showings (and also its part in the Judy Garland mystique, although she was far too old to play Dorothy). It’s said that dreams are better than any movie, and entertainments that for whatever reason didn’t happen tends to get the benefit of the doubt. If the Happy Harmonies are any hint, Hugh Harman may have turned the fragile “Little Prince” into an overblown, heavy-handed mess. (Orson Welles wasn’t exactly known for subtlety, either.)

Still, it might have had a better chance than the 1974 live action (speaking of heavy-handed) feature; which features some pretty bad animation of birds, overly self-consciously clever songs by Lerner and Loewe, an irrelevant Bob Fosse number, special effects that don’t quite come off, and a too-cute little boy playing the title character.

Outstanding work, Jim, Mike and Mark! I met Hugh at a Cinecon many moons ago and he expressed a rather low opinion of his work in animation, as well as utter disbelief that young people were interested in it. Now, I still love the films of Orson Welles and Hugh Harman, even more than I did then, but regard an adaptation of THE LITTLE PRINCE as more in the wheelhouse of Lotte Reiniger. The unrealized films of Orson and Hugh – too bad Harman’s “Gray’s Elegy” project did not get produced – held great promise, but, bear in mind, THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS and THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI both had over an hour of running time whacked, so this collaboration may well have met a similar fate. Oh well, at least we have PEACE ON EARTH, ART GALLERY, CITIZEN KANE and CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT; these films are their PET SOUNDS/SMILE.

There is a Claymation version of “The Little Prince” from 1979.

tt0079476/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_7_tt_7_nm_1_q_the%2520little%2520prince