This week we look at the seven pieces of Fleischer promotional art that appeared in Paramount Sales News from May through Oct. 1937. Only seven? For the first time since these weekly spot cartoons began appearing, none appeared in the trade publication for a period of two months, from mid-May through late September .

Well blow me down – what’s with this gap?

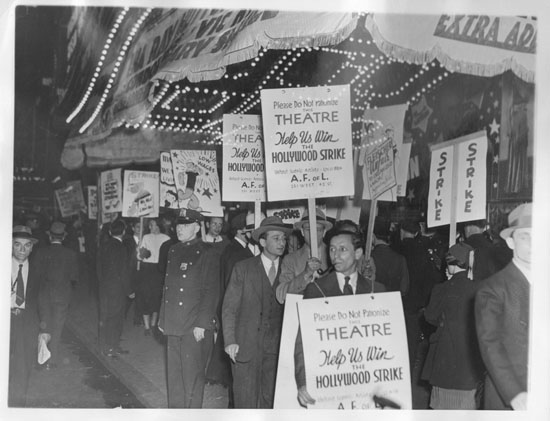

The low-rank employees went on strike against the gruesome Fleischer Studio conditions on May 7, 1937. They did not return to work until October 12. I think it’s no coincidence that the duration of the strike almost exactly matches the gap in these promotional drawings. It wasn’t a happy time for the studio, but one would think Paramount would want to boost the Fleischer product to combat the cartoon boycott the strikers were encouraging.

To give this post a bit more historic edge, here is an excerpt from the unpublished autobiography of Eli Brucker, who gained notoriety as the only Fleischer animator to not cross the picket line. He left the business shortly after the move to Miami. A shame as he was a real talent, as evidenced in these educational blog posts of Bob Jaques’s: 1/30/11 –

2/2/11

The following should be taken as Brucker’s own experience, and not necessarily 100% accurate. (I’ll only note where he makes the rare facts/figures error.) But Brucker’s recollections of the working conditions certainly do match many of his Fleischer coworkers’. And what are your qualifications to say that Brucker and them are wrong?

“Being that the demand for Popeye cartoons was constantly increasing, the Fleischer management tried to match the production to fit their needs. They made the mistake of having their help do this without increasing their cost. The animators and other workers were asked to work evenings without overtime pay. The only concession was to supply them with supper money. Naturally, this produced resentment and almost everyone took it easy and loafed on the job. The straw bosses told the Fleischers that they would put the screws on to several of the minor helpers and make an example of them so that others would see that it paid to hustle. However, this had the very opposite effect. The resentment increased. The pressure on the animators was far less, even though they loafed more than the minor help. The management considered them important and had no desire to antagonize them. But the minor help, consisting of inbetweeners, tracers or inkers, color fillers and some background artists, took the brunt of the pressure.

At first it worked. The pressure from the top caused the production to increase somewhat. This was a victory for the straw bosses. But it caused the assistants to hold a secret meeting and they formed a union. First they started a real slow-down. The top management was flabbergasted. They informed the straw bosses to make it tough for the supposed leaders. This strengthened the union so that all the assistants joined in and now they had a union strong enough to make a written demand to the top management to stop the pressure tactics and improve conditions by replacing the straw bosses with people from their own ranks. This was an unheard of arrogance as far as the management was concerned, and they increased their pressure still further.

Now, being organized, the assistants called a strike and threw a picket line around the building at 1600 Broadway and 48th Street where the Fleischers had their studios on the top floor.

The animators were not members of the union and they naturally were not on strike. But the assistants asked the animators not to pass their line. They, however, ignored the pickets and passed the line, with only one exception. I could not make myself pass this line, and stayed out. This had a tremendous effect on the strike and also on myself.

The strike was very bitter. It lasted six months. [TK: See above, it was five.] I was told by a good many people that my refusal to pass the picket line had a highly encouraging effect on the strikers. They had expected that almost all of the animators would refuse to pass their line, and they felt they were let down by their senior “brothers.” My not passing that line prevented them to break their ranks and kept the strike effective. It also caused the Fleischers to make me a marked man, as I found out later on. I felt that a trifle of consideration from the manaement would have prevented the strike, especially when the demand for Popeye cartoons was growing by leaps and bounds.

The Fleischer management sent one of the animators, who used to be friendly with me previously, to see me. He told me that if I would start to work again, I would get advantages of higher pay and most likely be advanced to becoming the next head of an animating group. I felt sorry for my friend who was given this painful job of trying to make me go against my nature. I told him that I would be glad to go back to work as soon as the picket line would no longer be there.

Some time later I discussed this situation with a certain party who told me that I should have accepted Fleischer’s offer. “Look at what you would have gained,” he said. To this my reply was, “But look what I would have lost if I took up their offer. This would have been my self respect. And that was too high a price for any man to pay.”

Fleischer animators on Strike in front of the Paramount Theatre in Times Square – in this 5/22/37 news photo. (click to enlarge)

Caption on back of Fleischer strike photo (click to enlarge). Thanks to Ryan Englade for sharing this photo.

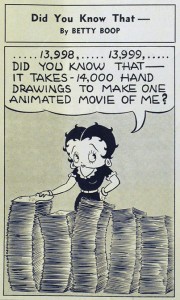

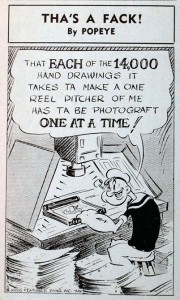

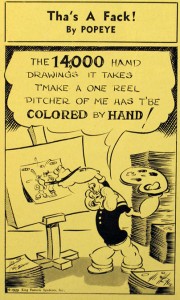

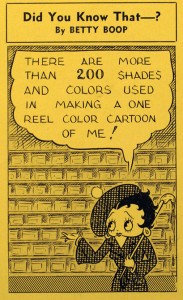

So ironic that this batch of promo’s center around the “Tha’s a Fack!” feature, given what was going on. How much blood, sweat and tears went into those 14,000 drawings and 200 shades?

Brucker had quite a bit more to say about the strike, and the aftermath. What else did he say? That information stays with me for now.

Well, OK, until the next post.

(click images below to enlarge)

Here are a few samples of what cartoon shorts the Paramount salesmen were pushing to theaters at the time these promotional pieces appeared in print.

Betty Boop in SERVICE WITH A SMILE (September 23rd 1937)

Popeye in THE FOOTBALL TOUCHER DOWNER (October 15th 1937)

THAD KOMOROWSKI is a writer, journalist, film restorationist and author of the acclaimed (and recently revised) Sick Little Monkeys: The Unauthorized Ren & Stimpy Story. He blogs at

THAD KOMOROWSKI is a writer, journalist, film restorationist and author of the acclaimed (and recently revised) Sick Little Monkeys: The Unauthorized Ren & Stimpy Story. He blogs at

And the horrible thing is that Popeye’s teammates just lie there for the rest of the cartoon after being flattened! Like they’re… dead! Even if the animators couldn’t spare a few seconds to show them getting up and hobbling off the field, leaving Popeye to carry on alone, it would have helped just to have the field mysteriously clear of flat, motionless bodies instead of leaving them in plain sight. The cartoon creeped me out because of the seemingly dead teammates when I saw it as a kid, and it still bothers me!

Many thanks for sharing the memories of Eli Brucker. It was very interesting reading. I really look forward to your book on New York studios if that is an example of the material you’ll be including.

Re: 10-20-37

And how many “one reel color cartoons” of Betty Boop did they make? (Rhetorical question. I assume everyone here already knows.)

Most of these are focused on the intensive labor that went into the product -I can understand why Paramount might have put these on ice for during the strike.

Paramount could not release the cartoons due to a successful boycott lead by The Musician’s Union and the Projectionists.

This was not Paramount’s decision, but the result of the force of the strike with the pictures being “booed” off the screen by striker plants in the theaters.

Wow – Thanks Thad for a most interesting ‘behind the scenes” write up.

No aroused box offices in this batch! They must have gone on a sympathy strike along with the Fleischer drudges.

I wonder if the strike had anything to do with the background paintings in some 1938 releases not being as detailed as the earlier ones? By 1939 the backgrounds are back to their previous level of detail.

Since the strike was in 1937, and the release schedule was backed up six months, this is difficult to determine since the Background Painters were not as largely involved with the strike. If you could be more specific about which cartoons you cite, I might be able to answer you. Is it “detail,” or technique you cite? There were two in use.

So, the reason that Popeye was always after Olive Oyl was because she was a high school sweetheart?

Considering how divisive and acrimonious the Fleischer and Disney strikes were, it’s actually amazing how much of an inconsequential footnote the Schlesinger/Warner unionizing process was. A six-day lockout, and that was it. No impact on the quality of the cartoons, no bitter schisms between friends and co-workers, none of that.

The Fleischer Strike was a “test case,” and the first labor strike in the motion picture industry. What was learned from this strike may have had an affect on the Schlesinger Strike.

I was fortunate enough to meet Eli Brucker in the late 1970’s. His son was a successful manufacturer of the some of the first flexible contact lens on the market. Eli drew cartoons for the company newsletter. I also submitted some cartoons to the “Continous Curve” newsletter. I met with Eli on a couple of occasions and was completely flabbergasted with his drawing skills. A major talent.

Having access to Harvey Deneroff’s extensive thesis on The Fleischer Strike, there was no mention of unpaid overtime, In fact several of the animators remarked that Fleischer’s was the only studio that actually paid overtime. This was not the case at van Beuren, and much of the tension that triggered the strike had started there and carried over when Van Beuren closed at the time that Fleischer was hiring. This sudden expansion resulted in crowded conditions, another issue of the strike, in addition to the quota pressures being imposed, which resulted in a “slowdown.”

A number is incidents occurred that resulted in the walkout and the start of the strike which this space cannot accommodate.