Donald Duck in Close-Up #9

In an earlier entry in this series, I made reference to the research that David Gerstein and I have been conducting into the life, times, and screen career of Donald Duck. While preparing an upcoming in-depth book about Donald, we’ve made a number of fascinating discoveries, some of which undercut the history that we’ve all learned over the years. It’s well known that Donald’s first appearance on the screen was in the Silly Symphony The Wise Little Hen (1934), and that he didn’t make a return appearance until a couple of months later in the Mickey Mouse short Orphans’ Benefit.

All of that is true. But as I mentioned in that previous column, studio documents reveal that the Disney story department started work in November 1933 on an outline titled “The Surprise Party,” slightly before they tackled The Wise Little Hen. The “Surprise Party” outline underwent a long evolutionary process, and finally emerged in its finished form as Orphans’ Benefit. In other words, Orphans’ Benefit was technically Donald’s second film to be produced and released—but the evidence suggests that the studio originally planned it as his first film.

All of that is true. But as I mentioned in that previous column, studio documents reveal that the Disney story department started work in November 1933 on an outline titled “The Surprise Party,” slightly before they tackled The Wise Little Hen. The “Surprise Party” outline underwent a long evolutionary process, and finally emerged in its finished form as Orphans’ Benefit. In other words, Orphans’ Benefit was technically Donald’s second film to be produced and released—but the evidence suggests that the studio originally planned it as his first film.

That’s an important distinction because it was Orphans’ Benefit that introduced Donald’s famous temper, the trait that would come to define him, more than any other, for at least the first ten years of his screen life. When the audience of little orphan mice discovered the Duck’s irascible nature, they seized on it and taunted him until he exploded in a full-blown tantrum. It would be the first of many. As he matured, and the Disney writers and animators continued to explore his character, additional personality traits would be revealed—but that volatile temper would remain a key element of his nature, never far below the surface.

Moreover, the early story work on the cartoon that would become Orphans’ Benefit made such an impression on the participants that some of them did remember it as Donald’s first appearance. One of those people was Walt himself. Two decades later, introducing Donald on television, Walt described Orphans’ Benefit as the Duck’s debut film. Generations of fans ever since have gently “corrected” Walt, pointing out that The Wise Little Hen had actually come first, but I think his statement is revealing. It suggests just how memorable those early story meetings must have been, as the artists and writers set out to build a character around Clarence Nash’s talking-duck voice. Regardless of the release dates of the two films, it was during those early meetings on “The Surprise Party” that a character began to take shape. For Walt and his collaborators, immersed in the creative process, those meetings were the defining moment when Donald Duck was born.

Moreover, the early story work on the cartoon that would become Orphans’ Benefit made such an impression on the participants that some of them did remember it as Donald’s first appearance. One of those people was Walt himself. Two decades later, introducing Donald on television, Walt described Orphans’ Benefit as the Duck’s debut film. Generations of fans ever since have gently “corrected” Walt, pointing out that The Wise Little Hen had actually come first, but I think his statement is revealing. It suggests just how memorable those early story meetings must have been, as the artists and writers set out to build a character around Clarence Nash’s talking-duck voice. Regardless of the release dates of the two films, it was during those early meetings on “The Surprise Party” that a character began to take shape. For Walt and his collaborators, immersed in the creative process, those meetings were the defining moment when Donald Duck was born.

As if to underline the primacy of Orphans’ Benefit, it was later singled out in a curious way. In the late 1930s, circumstances led Walt to consider the possibility of reissuing some of his earlier cartoons. His comments, recorded in conference, are fascinating in hindsight; he’s tempted to release the films to theaters again, but he’s ruthlessly critical of his studio’s earlier work. Viewing a 1929 cartoon from the perspective of 1939, he seems excruciatingly embarrassed at the animation and technical details. The answer was to remake the cartoons—not simply to revisit the same story lines, but to produce exact scene-for-scene duplicates of those early shorts, identical in every way except for character design and visual details.

As if to underline the primacy of Orphans’ Benefit, it was later singled out in a curious way. In the late 1930s, circumstances led Walt to consider the possibility of reissuing some of his earlier cartoons. His comments, recorded in conference, are fascinating in hindsight; he’s tempted to release the films to theaters again, but he’s ruthlessly critical of his studio’s earlier work. Viewing a 1929 cartoon from the perspective of 1939, he seems excruciatingly embarrassed at the animation and technical details. The answer was to remake the cartoons—not simply to revisit the same story lines, but to produce exact scene-for-scene duplicates of those early shorts, identical in every way except for character design and visual details.

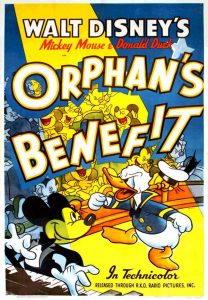

Several earlier Disney pictures were considered as candidates for this treatment, but only one was completed: Orphans’ Benefit, reworked and released in August 1941. This second Orphans’ Benefit is in Technicolor, and “updates” the design of the characters to reflect their 1941 appearances, but is otherwise such an exact remake that it reuses the soundtrack of the 1934 original! The resulting pair of films makes for a fascinating side-by-side comparison. We have every reason to believe that Walt and his colleagues, from the standpoint of 1941, considered the second version an improvement on the first.

However, we also have reason to believe that Walt and Roy both had second thoughts about these slavishly exact remakes before the first one had progressed very far. Orphans’ Benefit was completed and submitted for copyright in the spring of 1941, and at that point Roy contacted Reg Armour at RKO Radio, the studio that distributed the Disney films. In the interest of total transparency, Roy explained, almost apologetically, that this was not exactly a “new” cartoon. He later wrote to Walt: “I told him … that we didn’t want to deliver it under any false pretenses—we were going to deliver it for the price it cost to redo it.” But Armour was unfazed: “Reg said he remembered the picture and thought it was a good one, and thought there were a number of others that could be done this way, too. He thought that nothing should be said about it unless capital is made of the fact that it was the first Donald Duck.”

In the end, however, the Disney studio abandoned this program, and the two versions of Orphans’ Benefit remained an anomaly in Disney history.

In the end, however, the Disney studio abandoned this program, and the two versions of Orphans’ Benefit remained an anomaly in Disney history.

As interesting as this story is, it comes with an unfortunate side effect. Thanks to the production papers kept on file by the Disney artists—and scrupulously preserved today by the Walt Disney Archives and the company’s Animation Research Library—the historian can compile detailed credit lists for most of the Disney cartoons from the early ’30s on. Orphans’ Benefit is one exception. The artists retained those papers not for the benefit of historians who would come along eighty years later, but for their own use. Accordingly, when director Riley Thomson set out to overhaul Orphans’ Benefit, he relied on the drafts and exposure sheets from the 1934 production—and by the time the new version was finished, all the surviving papers for both versions were jumbled together in the same file. As a result, despite the best efforts of the Archives and the ARL, it’s no longer possible to document complete, definitive animation credits for either version of Orphans’ Benefit.

However, we can reconstruct some key details. In the 1934 original, the long adagio dance number with Goofy, Clarabelle, and Horace Horsecollar is animated by the great Norm Ferguson. Les Clark, already a veteran and later one of Disney’s Nine Old Men, animates Clara Cluck’s operatic performance—a noteworthy credit, for he would come to specialize in the character. Clara Cluck never did become a major member of the Disney cartoon stable, but she did make a number of return appearances, and Clark was always the go-to artist for her scenes. But the star performance here is that of Dick Lundy, assisted by junior artist Dick Williams, who contributes Donald Duck’s scenes—both his literary recitals and his mighty burst of fury. Donald’s hopping, fist-swinging action created a sensation within the studio and in theatrical showings of the cartoon. It cemented Lundy’s already secure status in the Disney animation hierarchy, and established Donald’s explosive temper for all time.

However, we can reconstruct some key details. In the 1934 original, the long adagio dance number with Goofy, Clarabelle, and Horace Horsecollar is animated by the great Norm Ferguson. Les Clark, already a veteran and later one of Disney’s Nine Old Men, animates Clara Cluck’s operatic performance—a noteworthy credit, for he would come to specialize in the character. Clara Cluck never did become a major member of the Disney cartoon stable, but she did make a number of return appearances, and Clark was always the go-to artist for her scenes. But the star performance here is that of Dick Lundy, assisted by junior artist Dick Williams, who contributes Donald Duck’s scenes—both his literary recitals and his mighty burst of fury. Donald’s hopping, fist-swinging action created a sensation within the studio and in theatrical showings of the cartoon. It cemented Lundy’s already secure status in the Disney animation hierarchy, and established Donald’s explosive temper for all time.

For the 1941 remake, Riley Thomson worked mostly with a crew of junior artists. Surviving papers suggest that Mickey’s scenes were redrawn primarily by Sam Cobean, Bob McCrea, and Art Elliott. Chester Cobb worked over Norm Ferguson’s animation of the adagio dance, and Les Clark’s original Clara Cluck pencil animation apparently was simply reused intact. And Donald Duck’s star-making performance? For those scenes, Thomson had the services of Johnny Cannon, who had long since established himself as one of the studio’s “Duck men.” Cannon retained Dick Lundy’s original action, but completely reworked Donald’s design so that he would be recognizable as the Donald Duck that audiences had come to know by 1941. Today we have the luxury of two alternative versions—the fresh, vivid 1934 original and the polished 1941 remake—of the performance which, in the eyes of Walt Disney himself, introduced Donald Duck to the world.

Thanks to Michael Ruocco for creating this comparison video:

Addendum

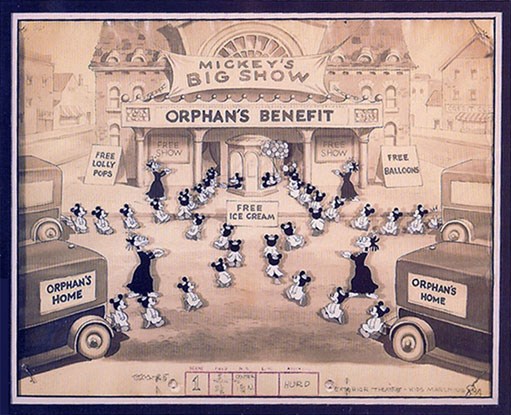

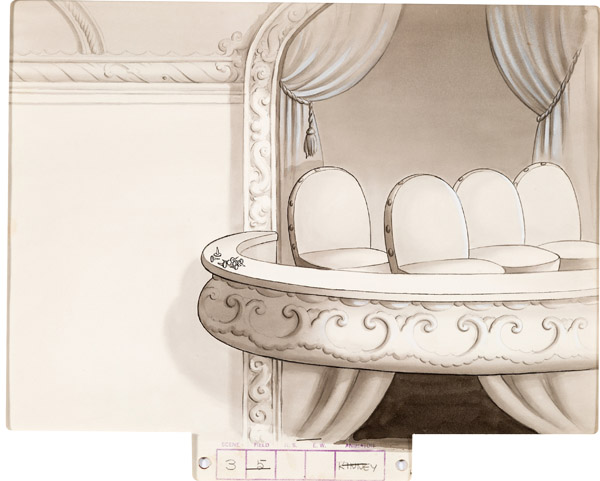

Thanks to our friend Devon Baxter, who has supplied scans of two background paintings (one of them paired with a cel) from the original version of Orphans’ Benefit. These paintings are stamped with a space for the animation credit, and so help to certify the animation credits for two additional scenes in the film. The first is the opening LS showing the orphans marching into the theater (the last time we see them doing anything in an orderly, obedient way!). This crowd scene, a cycle with plenty of repeats, is identified as having been animated by animation legend Earl Hurd, who had just joined the Disney staff in April 1934, and who would soon transition to the story department. (See John Canemaker’s great book Paper Dreams, pp. 109–114.)

The other scene is sc 3, another crowd scene and presumably a far more difficult one (because the action is so wildly varied), showing the orphans settling into a box and preparing to wreak their mischief. This was animated by Jack Kinney, still in the early years of what would be a distinguished Disney career of his own. This is an extremely useful addition to the credits that could be compiled from archival sources. Thank you, Devon!

Next Month: The Haunted Duck

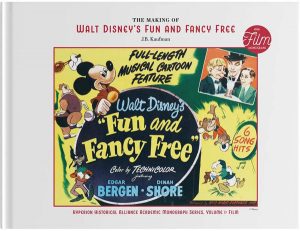

I’d like to congratulate J.B. Kaufman on his monograph, The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’, and its being named by the Theatre Library Association as a finalist for the 2019 Richard Wall Memorial Award. The book is a must-have – and I urge you to order it today.

I’d like to congratulate J.B. Kaufman on his monograph, The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’, and its being named by the Theatre Library Association as a finalist for the 2019 Richard Wall Memorial Award. The book is a must-have – and I urge you to order it today.

I’d also like to call your attention to the Hyperion Historical Alliance 2020 Annual which was just published this past week. It’s a choice collection of deeply researched articles featuring new discoveries that will transform your understanding of Disney history. J.B contributes a thoroughly researched look at the Canadian Bond Trailers of 1941-42. Mindy Johnson has new research on Betty Smith-Totten, the game-changing artist who was among the early women who advanced their talents within the ranks of animation at Disney Animation Studios – as well as at Warner Bros. cartoons! Didier Ghez writes about Grace Huntington’s work with Disney Story Dept. with more about the Mickey Mouse revivals, Disney Archivist Kevin Kern gives a detailed account of the Mary Poppin’s premiere, and Matt Moryc presents “A Preview of Disney’s World,” the definitive history of Walt Disney World’s first introduction to the public in Florida. Great stuff indeed! Order it here. – Jerry Beck

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

Another fascinating article as always.

In your Silly Symphony book you describe The Ugly Duckling (1939) as a “loose” remake.

Although clearly different in many ways from the original, wouldn’t this title have been part of this remake programme – at least in some form?

(And no, I do not include the Laugh-O-Gram and the feature Cinderella as part of this programme!)

Thank you, Michael. Yes, you’re right, there were a number of Disney remakes — as we understand them in the more traditional sense — around this time. For example, “Mickey’s Pal Pluto” was remade as “Lend a Paw.” I do think “The Ugly Duckling” is about as loose a remake as one could imagine. (Perhaps even looser: the film we know as “The Old Mill,” believe it or not, evolved out of a plan to do an updated version of “Night”!) So, yes, you’re quite right — but I do think of this exact scene-for-scene retread of “Orphans’ Benefit” in a different category. It amounts to a makeover, bringing the film up to what was, at the time, considered a higher standard.

I can think of at least one other respect in which the remake is superior to the original: punctuation! The title card, and the theatre marquee in the establishing shot, read “Orphan’s Benefit” in the 1934 version, but “Orphans’ Benefit” — with the apostrophe at the end of the word, where it belongs — in the 1941 version. The earlier mispunctuation implies that only one orphan is benefitting. As Jimmy Durante might have put it: “This apostrostrophe is a regular catastrostrophe!”

Also, I believe Donald’s final word in the 1934 version was “Nuts!” rather than “Phooey!”

You didn’t mention which other cartoons were under consideration to be remade, but I think “Mickey’s Revue” (1932) would have been a good candidate, as the debut of Dippy Dawg aka Goofy.

Good catch! Not only was “phooey” a familiar expression for Donald by the early ’40s, but the term “nuts” was now formally regarded as a “vulgarism” by the Production Code, and its use here might have been discouraged by the Breen office.

The 1934 film’s title card is a recreation done for its 2002 DVD release (the film wobble on the title art but not the text is a dead giveaway), so I wouldn’t necessary blame the ’30s Disney crew for an error that may have been made nearly 70 years later. Changing Donald’s line is odd; the ’34 film was an August 11 release, and so is post-Code as well (Betty Boop was settling down with Freddy and adopting Pudgy by that point in ’34). Maybe it snuck by because it began production beforehand, but they also had no problem with Donald exclaiming “Aw, nuts to you!” at the end of “On Ice”, a September 1935 release. The phrase crops up in shorts after ’41 as well; over at WB, Elmer Fudd gets in an “Aw, nuts” at the end of “Pests for Guests” (1955).

Good for you, Paul, for catching that misplaced apostrophe, and for you, R.L., for noticing that the 1934 title card shown here was the later reconstruction. Yes, in fact, the word was spelled correctly — that is, in the plural possessive, Orphans’ — in the original 1934 prints. We know that from several pieces of evidence, but primarily from the copyright papers. The staff at the Copyright Office was scrupulous in those days about registering the title *exactly* as it appeared onscreen, and would correct any discrepancies in the registration papers by hand. In fact, in this particular case, the title was shown on one of the registration papers without any apostrophe at all, and someone at the Copyright Office added one in pencil — *after* the “s”. Nitpicky, yes, but the copyrighted title of a published work was the legal identification by which the work would be known, and they took pains to get it exactly right.

Even if the original title card had correct punctuation, the marquee sign in the opening shot read “Orphan’s Benefit” in the 1934 original and the corrected “Orphans’ Benefit” in the 1941 remake.

R.L.,

the recreated ORPHANS’ BENEFIT title card was actually originally made in 1993 for the “Disney’s Exclusive Archive Collection” LaserDisc set “Mickey Mouse: The Black and White Years”. The DVD equivalent (the “Walt Disney Treasures” set “Mickey Mouse in Black and White”, which features all 33 shorts released — or all 34 shorts planned to be put — on the LD set), as you said, retains this title card.

Very interesting, and the side-by-side comparison is also excellent (the fact that the same soundtrack was used was a big help, I would think).

I like to imagine all of those “orphans” are actually Mickey’s illegitimate children.

I just noticed that in the remake, Donald doesn’t semi-morph into Jimmy Durante when he says “Am I mortified!”

Durante’s career had had its ups and downs. He was prominent in the early 1930s, and in fact was semi-teamed with Mickey in MGM’s “Hollywood Party.” His career then went into a kind of eclipse in the late 1930s and early 1940s, before getting a strong revival on radio with a teaming with Garry Moore starting in 1943, which set off another group of cartoon usages (think “Swooner Crooner” and “Gruesome Twosome” from WB). At the time of the remake, Durante’s career was in the trough, which might have prompted the deletion of the gag.

I wonder if there might simply have been a reluctance for the newer Donald to appear off-model by transforming his bill into a schnozz. After all, Popeye gave an “imperskonation” of Jimmy Durante in “Puttin’ on the Act” (1940).

It might also be that after Donald’s redesign, the shorter beak did not lend itself to a Durante impersonation.

Am I the only one who much prefers the late ’30s version of Mickey (and the orphans) to the 1941 version? I’ve always found that look (with the white around the eyeballs altering shape to act as eyebrows) as far more expressive than any later iteration of Mickey’s design. It even works in color, as seen in “The Brave Little Tailor”.

I wonder why the Donald animation mirrors at 8:06. I guess it matches the end of the previous Donald shot better, but there’s plenty of time during the shot of the orphans for him to have turned his head the other direction.

Another good catch! Yes, I find this fascinating too. The original 1934 exposure sheets (the surviving ones) have notes in Walt’s handwriting, indicating that the already-completed animation for some of Donald’s scenes was to be reversed — probably for purposes of continuity. For whatever reason, Cannon *didn’t* reverse the action when he remade the scenes in 1941.

Another Disney remake was started of “Mickey’s Man Friday”, don’t know the exact year they started it. There are numerous model sheets of the redesigned characters, “Friday” was redesigned to look a lot like Gottfredson’s comic strip character, used in the Mickey Mouse comic strip story: “Mickey Mouse Meets Robinson Crusoe”, syndicated in Dec. 1938 through April, 1939. Perhaps they reconsidered the project, after they looked at it from a stereotypical angle? I wonder if they completed the animation for it?

Enjoyed this article very much. What a treat to watch the two versions side by side! I also seem to prefer the original 1934 version. The evolving creativity and talent that was occurring in the making of the 1934 toon is wonderful to recognize and contemplate. In the same breath, though, Mickey and Donald in the 1941 color version made me smile since I saw them fully developed as the character models I most identify them with. I am in awe of how Disney captured and managed the talent that solidified these characters in mine and the lives of so many others. (I’m looking forward to the book on Donald Duck. I have Taschen’s book on Mickey and it is a favorite of mine.)

Thank you, Cynthia. The Taschen Donald Duck book was supposed to be out by the end of this year, but that plan, like so many others, was impacted by the pandemic. Now I’m told that the wheels are turning again … so my fingers are crossed!

Page 2 of the remake draft still exists, with handwritten annotations on some of the terminology used. I can’t seem to find it online, but I saved a copy, and it reads:

11 | CANNON | 12-0 | CU – Duck starts to recite “Little Boy Blue.”

12 | CLINTON | 4-0 | CU – Kid in audience blows nose. (Fish horn)

13 | CANNON | 15-8 | MCU – Duck gets mad, bawls kid out.

14 | GRAY | 4-12 | CU – Mickey in wings, tells Duck to be quiet.

14.1 | CANNON | 10-12 | MCU – Duck calms self and recites “Little Boy Blue.”

14.2 | GRAY | 4-0 | MLS – Balcony. All the kids blow noses. (Assortment of horns)

14.3 | CANNON | 18-0 | Duck very mad – Mickey hooks Duck off stage.

14.4 | GRAY | 6-0 | MLS – Kids in audience all laugh.

15 | COX | 12-11 | LS – Stage – curtain up – Cow, Horse and Goof start adagio dance.

So, we see (Maxwell? Errol?) Gray re-animating scenes of Mickey and the kids, one shot by Walt Clinton of one of the kids, and the first scene of the dance re-animated by Rex Cox, rather than Chester Cobb.

John, thanks for sharing this! Can you tell me the date of this draft? I’ve seen a complete draft for the remake at the Archives, but it’s dated 31 October 1939 and is significantly different from what you’re describing here. For starters, most of the credit boxes are empty! I’m guessing yours is later, and would love to know the date. In any case, thanks again for sharing — very interesting!

I noticed it’s from Hans Perk’s collection, so he must have posted it on his A Film L.A. blog, though I can’t find it now. (You may want to get in touch with him?) It’s dated 25th July but the year has been cut off, probably by the copying machine. It is apparently Draft No. 2, though.

Pretty interesting that Walt was so embarrassed of his decade-old output…But just far as the animation went, seemingly considering the story beats, gags and timing so perfect as to not mess with them in the slightest.

Excellent article as always; cannot wait for the book. It’s so nice to hear Don was always meant to be a breakthrough star alongside Mickey and Co.

I generally preferred the 1934 original over the remake. I used to find the animation in the 1941 remake stilted at times, but after watching that side-by-side comparison, it looks alright. Mickey even seems a little more expressive in the remake. Donald’s “Am I mortified” bit looks weird without the Durante visual to accompany it.

I’m kind of surprised they didn’t try to incorporate new gags into the short, kinda like what WB would do when they remade their B&W shorts into color.

This particular short seemed to cause no end of confusion for Disney’s history and VHS market throughout the late 80s and 90s. Most history books would list “Orphan’s Benefit” as a 1934 short, but no acknowledgement of the 1941 remake. And some VHS tapes that talked about Disney’s history, when showing footage of “Orphan’s Benefit”, they’d show clips from the 1941 remake, but identify it as from 1934. Oops.

The original 1934 “Orphan’s Benefit” along with “The Band Concert” prove how much younger and smaller Donald was than even Mickey and accounts for much of his immaturity and supposed “cowardice” in other works like Floyd Gottfredson and early Al Taliaferro.

But he was still always fierce and fiery.