We all know that Mickey Mouse started life as a child of the movies, and his native habitat was the one-reel animated cartoon. But it’s also well known that he invaded the world of newspaper comics early in life. The daily “Mickey Mouse” comic strip began to appear in newspapers in January 1930, little more than a year after the first showings of Steamboat Willie. By this time Mickey Mouse was already a sensational phenomenon in popular culture, and his appearance in the comics immeasurably boosted his fame. In those pre-television, pre-Internet days, newspaper comic strips were an omnipresent diversion in American life. Appearing in both the movies and the daily newspaper, Mickey enjoyed a powerful presence. He was everywhere!

Originally the strip was written by Walt Disney and drawn by Ub Iwerks, the two collaborators who had brought Mickey to life in the first place. After Iwerks’ departure from the Disney studio the artistic duties were passed to other hands, and in the spring of 1930 the Mickey strip was taken over by Floyd Gottfredson, a young artist who would continue to produce it for the next 45 years. Now, thanks to The Floyd Gottfredson Library, edited by our own David Gerstein, we have a precious record of the entire history of the Mickey Mouse comic strip, including the pre-Gottfredson beginnings.

Originally the strip was written by Walt Disney and drawn by Ub Iwerks, the two collaborators who had brought Mickey to life in the first place. After Iwerks’ departure from the Disney studio the artistic duties were passed to other hands, and in the spring of 1930 the Mickey strip was taken over by Floyd Gottfredson, a young artist who would continue to produce it for the next 45 years. Now, thanks to The Floyd Gottfredson Library, edited by our own David Gerstein, we have a precious record of the entire history of the Mickey Mouse comic strip, including the pre-Gottfredson beginnings.

And a fascinating history it is. In the early months and years we can see the Disney studio experimenting with its fledgling cartoon star, trying to find the best way to present him to the public. The theatrical cartoons and the daily strip become, in effect, two parallel tracks, operating independently but often intersecting. Inevitably, Mickey’s screen adventures are reflected in the comics in varying ways. The first eight installments of the strip hew closely to his first theatrical short, Plane Crazy—picturing Mickey’s construction of, not one, but two makeshift planes, his hero-worship of Lindbergh, and the assistance of the friendly dachshund (here named “Wienie”)—with a standout gag from Plow Boy (1929) thrown in for good measure. That was only the beginning; gags, situations, characters, and even specific poses from the films continued to show up in the strip for years afterward.

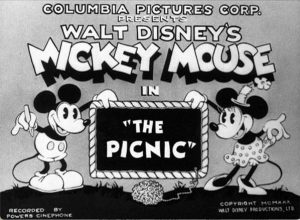

Early in 1931, however, the studio tried a particularly fascinating experiment that would remain unique in Mickey comics history. During the first year of the strip, Gottfredson had established what would become his specialty: the adventure serial, often presented in an extended continuity that might run for weeks or months. But in January 1931 he broke that pattern, twice in succession, for one-week continuities based upon specific films. For six days, Monday through Saturday, the Mickey Mouse comic strip became a self-contained reenactment of a recent Mickey Mouse film—sometimes directly duplicating the screen gags, sometimes not, but unmistakably tied to its cinematic source. Today we’re going to take a close look at the first of these film/comic strip pairings: The Picnic. Let’s start with the film.

CM 8

Released 23 October 1930 by Columbia Pictures

Copyright 24 October 1930 by Walter E. Disney & Columbia Pictures Corp. (MP2049)

Director: Burt Gillett

Animation: • Dave Hand (Mickey in opening scene drives to Minnie’s house; LS animals steal

picnic lunch; clouds, lightning, rain; Mickey grabs tablecloth, basket, and phonograph as birds and squirrels scatter)

•Jack King (Minnie greets Mickey and wants to bring Rover)

•Charles Byrne (Rover out of doghouse and runs to gate; Rover chases rabbit into hole)

•Charles Byrne (Rover out of doghouse and runs to gate; Rover chases rabbit into hole)

•Norm Ferguson (Mickey’s first look at Rover; Rover barks and bites flea; Rover sniffs at

tree and car, exhaust gag)

•Dick Lundy (Mickey ties Rover; start of trip, Mickey and Minnie whistling; Mickey into car in rain)

•Johnny Cannon (rabbits dance; Rover chases rabbits and pulls car; ants steal olives,

pickles, sugar; Mickey and Minnie run as rain starts)

•Les Clark (Rover chases rabbit between two holes; squirrels steal food)

•Ben Sharpsteen (LS Minnie spreads picnic while Mickey starts phonograph; Mickey and

Minnie waltz)

•Tom Palmer (birds dance and steal food; bees in honey jar; Mickey, Minnie, and Rover in

closing scene, windshield wiper gag)

•Wilfred Jackson (Mickey and Minnie on log)

•Jack Cutting (flies steal cake)

•Frenchy de Trémaudan (ants steal sandwich and cheese)

Layouts: 28 August–13 September 1930

Animation: 29 August–25 September 1930

Poster drawn by Dick Lundy, 29–30 August 1930

This cartoon has always been a personal favorite of mine; even by the high standard of the other foundational Mickey cartoons, this one is particularly charming. In addition, it has points of historical interest. Most obviously, it’s one of the formative appearances of the dog who would later evolve into Pluto. Here his name is “Rover,” and most of his gags revolve around his ungainly size. His animation in this picture is in the hands of six different animators, but, tellingly, Norm Ferguson is responsible for most of it. Ferguson’s animation of a pair of bloodhounds in The Chain Gang, a few weeks earlier, is widely accepted today as the origin of the dog who would become Pluto. The Picnic is only the dog’s second appearance. Ferguson’s Chain Gang scenes had created a sensation at the studio, and one of them, the closeup of the dog’s sniffing action directly into the camera, became a frequently reused staple of the studio’s “stock library” of animation. It reappears in this film, and would continue to turn up in further Disney cartoons as late as 1939. In the meantime, Pluto would become Ferguson’s signature character as an animator.

The Picnic also displays interesting connections with other Disney pictures. The birds and squirrels at the picnic site are visitors from recent Silly Symphonies, and Rover’s pursuit of the rabbit between two holes in the ground marks the welcome return of a visual device that had appeared in some of the Alice Comedies. And, as always, it’s intriguing to watch Mickey pass through the hands of different animators, no two of whom drew him exactly alike during this period. Ben Sharpsteen had joined the Disney staff in 1929, and his touch is unmistakable in his scenes here, not only in Mickey’s and Minnie’s wide-mouthed grins but in their slow, floating movement during the waltz. Wilfred Jackson’s scenes display his trademark placement of Mickey’s (and Minnie’s) ears and their paddle-like hands—and so on.

Less than three months after the theatrical release of this cartoon, the corresponding comic continuity appeared in newspapers.

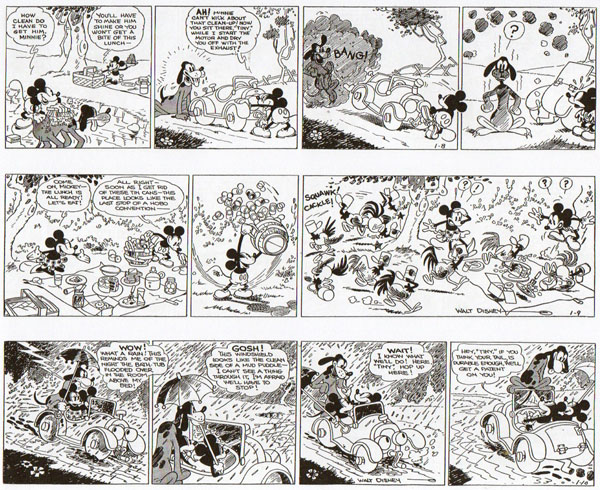

5–10 January 1931, plotted and penciled by Floyd Gottfredson, inked by Earl Duvall.

Complete strip below (click panels to enlarge)

At first glance, the most obvious feature of this continuity is its striking fidelity to the film. In fact, it adheres so closely to the film that the similarities highlight the discrepancies, and tell us something about Gottfredson’s and the studio’s priorities. Once again Minnie’s pet dog is a major player in the story, but in January 1931 he shows no signs of developing into a long-term character. Here his name here is “Tiny,” and visually he resembles neither the dog in the film nor the later character we all recognize. As the year 1931 continued and Pluto gradually assumed his long-term identity in the movies, the comics would follow suit. During the summer months, the dog in the comic strip would recognizably become Pluto.

The gags in this continuity are taken directly from those in the film, but Gottfredson generally adds some little twist of his own. Once again “Tiny” takes off after a rabbit and is fully capable of dragging Mickey’s roadster along with him, but here the rabbit aggravates the situation by leading the dog through a hollow log! The car-exhaust gag from the film reappears in the strip, but here Gottfredson sets up the gag with Mickey’s effort to give Tiny a bath. (And just as the car is slightly anthropomorphized in the film, note that it appears in some of these comic panels with headlight “eyes,” and seems to take a particular interest in Minnie’s picnic lunch!) The continuity concludes on Saturday the 10th with the windshield-wiper gag, lifted verbatim from the closing scene in the film.

This direct pairing of a cartoon short and a comic-strip continuity is, I think, a fascinating anomaly in Disney history. And this first instance was followed immediately, the next week, by another. We’ll look at that one next time.

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

When my mother was a little girl, she had a book called “Mickey Mouse Movie Stories”. About ten of his animated adventures (I remember “The Gorilla Mystery” was one) were written out as text, accompanied by black-and-white illustrations from the cartoons. In the lower corner of each page was a picture of either Mickey or Minnie, and when you flipped through the pages, you made them dance! My mother was born in 1923, so this book must have been published very early in Mickey’s history. My mother’s family moved about half a dozen times when she was growing up; and the fact that she held onto that book through all those moves, and was ultimately able to share it with her own children, shows how precious it must have been to her.

It occurs to me now that the phrase “Movie Stories” in the title implicitly acknowledges Mickey’s presence in other media, specifically the newspaper comic strip. Books such as this, being in a more solid and permanent format than either films or comic strips, would have been another key component in establishing Mickey as a cultural phenomenon.

When were the Mickey Mouse comic strips first collected and published in book form? And in the early 1930s, were there any original Mickey Mouse stories that appeared in books, but not in the animated cartoons or the comic strip?

The Columbia dialogue transcript for THE PICNIC reveals a gag so out-there that one would never pick it up from the muffled enunciation heard on screen.

When Minnie musically asks, “Oh, can I bring my little Rover?,” Mickey replies “Sure hoping that your lips don’t rove-r.”

The entire use of the name “Rover” (actually “Little Rover,” on the doghouse placard) seems like it must have evolved from the the background theme, “What D’ye Mean, You Lost Your Dog?”—a Gerstein/Rosengarten household favorite…

I have two large comic strips to sell from 1930s. I want to auction them. How much are they worth?