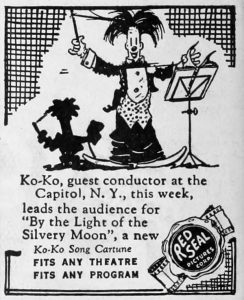

By 1925, Max Fleischer was holding his own in the animation firld (though most of the publicity was going to Pat Sullivan’s Felix the Cat cartoons. Max had already been in liaison with Lee DeForest for his sound on film experiments, and with Alfred Weiss in forming Red Seal Prictures. Distribution was handled on a “States Rights” basis, not through any of the major or minor studios. Alfred Weiss was one of the Weiss Brothers, who released several comedy shorts, low budget Westerns, and a few features, under the name “Art Class Pictures”. (As cheaply made as they were, it’s a wonder that wags of the time didn’t specifically note that the puctures had neither art nor class.) Otherwise, the Fleischer product continued to use older songs, as opposed to the latest popular favorites. Following is another batch of episodes, all believed to be from 1925, that have yet to appear among collectors’ circles in film form, and may be potentially lost to the ages.

By 1925, Max Fleischer was holding his own in the animation firld (though most of the publicity was going to Pat Sullivan’s Felix the Cat cartoons. Max had already been in liaison with Lee DeForest for his sound on film experiments, and with Alfred Weiss in forming Red Seal Prictures. Distribution was handled on a “States Rights” basis, not through any of the major or minor studios. Alfred Weiss was one of the Weiss Brothers, who released several comedy shorts, low budget Westerns, and a few features, under the name “Art Class Pictures”. (As cheaply made as they were, it’s a wonder that wags of the time didn’t specifically note that the puctures had neither art nor class.) Otherwise, the Fleischer product continued to use older songs, as opposed to the latest popular favorites. Following is another batch of episodes, all believed to be from 1925, that have yet to appear among collectors’ circles in film form, and may be potentially lost to the ages.

The Trail of the Lonesome Pine (1925, probably silent). The song is from 1913, and was recorded for Columbia by Albert Campbell and Henry Burr. Edna Brown (actually Elsie Baker) and James F. Harrison recorded for Victor. Dave and Alice Taylor recorded it acoustically on Supertone. In the 30’s. Clayton McMichen (formerly of Gid Tanner’s Skillet Lickers) recorded a Western-swing flavored version with his Georgia Wildcats on Decca. Late revivals included Russ Morgan on Decca, Arthur Godfrey (who for a time used it as a theme song) on Columbia, and Ralph Flanagan on Victor. In England, versions included H. Cove on acoustic “The Winner” from Edison Bell, The Hill Billies on Regal Zonophone, and the Imperial Guard Band on Phoenix. The song would provide the title for Paramount’s first three-strip Technicolor feature, including prominent roles for Fred McMurray, Henry Fonda, and a young Spanky McFarland, but would be most notably remembered in film as a featured specialty for Laurel and Hardy in Way Out West.

When I Lost You (1925, silent) – A 1913 Irving Berlin song – his first success with a sentimental song, allegedly inspired from the death of his first wife. Victor gave it to Henry Burr. Manuel Romain recorded it for Columbia. Later versions included Bing Crosby on Decca, Ken Griffin on Columbia, the Philharmonica Trio on Capitol, and the Greater Kensington String Band of Philadelphia on Guyden.

Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1925, silent) – Another Irving Berlin super-hit. Recorded in 1911 by Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan for both Victor and Columbia. Bessie Smith recorded it electrically for Columbia in 1927. The Boswell Sisters jazzed it up for Brunswick. Benny Goodman performed it in swing on Victor. Bob Wills gave it a Western swing flavor on Vocalion. Bing Crosby and Al Jolson dueted it for Decca. And countless jazz versions have covered this standard, too numerous to mention – and of course, Alice Faye:

My Wife’s Gone To the Country (1925, silent) – Yet another Berlin hit. Recorded in 1910 by Collins and Harlan for Columbia. Harry Fay recorded it in England for HMV. Unlike the other Berlin numbers, this one doesn’t seem to have received any subsequent recording revivals.

Oh, Suzanna (1925, silent) – Stephen Foster finally cuts in on Berlin’s action. Obviouly because of its age, no recordings date back to its heyday. It was included in a medley by The Great White Way Orchestra on Victor circa 1923. Wendell Hall also got it on wax for Victor in 1924. Arthur Fields recorded it for Grey Gull in 1927. Vernon Dalhart, Carson Robison and Adelyne Hood joined forces to perform it on electrical Victor and Regal. Vaughn DeLeath recorded it as the last Edison Diamond Disc to be released. Richard Crooks gave it some class on Victor Red Seal. The Light Crust Doughboys served it up country style on Vocalion. Al Jolson performed it on a late Decca side. The RCA Folk Dance Orchestra pressed it in the 1950’s. And countless children’s versions sustained it as a standard.

Toot Toot Tootsie (1925, silent) The song “Toot Toot Tootsie, (Goo’Bye)” was of fairly recent vintage for Fleischer’s tastes, released in late 1922. It became immediately associated with Al Jolson, who recorded it for Columbia. Other versions included Billy Jones and Ed Smalle for Victor, and Arthur Fields on Grey Gull. Dance band versions included the Oriole Terrace Orchestra on Brunswick, the Benson Orchestra of Chicago on Victor, and Bailey’s Lucky Seven on Gennett. The song became something of a standard, and Jolson revived it for Decca when his own career revived in the 1940’s. Mel Blanc covered it for Capitol, doing his best impersonation of Jolie in a parody of the hit, ending with Porky Pig saying, “Th-th-that’s all, Al!”

When I Leave the World Behind (1925, silent) – The song is another Irving Berlin sentimental ballad from 1915, recorded by Henry Burr on Victor, Sam Ash on Columbia, and later revived by Bing Crosby on Decca.

I Love a Lassie (1925, silent) – a signature Scottish novelty, recorded as early as 1905 by Sir Harry Lauder on G & T (Gramophone and Typewriter), which can also appear in repressings on HMV, Zonophone, and Victor black label. Later remakes were performed by him in 1909 on Victor purple seal, 1911 for Edison Amberol cylinder, and 1926 for HMV (12″) and Zonophone (10″). The HMV, electrically recorded, remained in the American Victor catalogue for at least 20 years. Covers were issued by Sandy Shaw on Columbia, also issued on the “Oxford” label pressed up for Sears, Roebuck, and one Scott Blakely on Cameo.

To be continued.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

James Parten has overcome a congenital visual disability to be acknowledged as an expert on the early history of recorded sound. He has a Broadcasting Certificate (Radio Option) from Los Angeles Valley College, class of 1999. He has also been a fan of animated cartoons since childhood.

The Mel Blanc “Toot Toot Tootsie” is a great record–Spike Jones, eat your heart out! The instrumental backing is so fast, I wonder if it was artificially sped up? If not, Bill May’s musicians must have been worn out at the end of that session.

I can think of at least one subsequent revival of “My Wife’s Gone to the Country”: in the 1931 Fleischer Screen Song of that title. Betty Boop, still sporting her poodle ears, has a cameo.

You wouldn’t expect a blackface entertainer like Al Jolson to expurgate an offensive term from a famous minstrel song, but that’s precisely what he did in “Oh Susanna”. He begins the second verse: “I jumped aboard the telegraph and traveled round the bend, / Electric fluid magnified and killed five hundred men.” In the original lyrics, he travels not “round the bend” but “down the river,” the electricity killing five hundred — well, it’s not a true rhyme, and it starts with N. I wonder how the lost Fleischer cartoon might have handled that verse.

I nearly fell out of my chair laughing at Mel Blanc’s rendition of “Toot Toot Tootsie”!

Could Billy May play fast? Try on for size sometime another Mel Blanc classic recorded for Capitol, “Trixie, the Piano Playing Pixie”, which is on YouTube. This complicated recording was recorded in four parts: (1) a sped-up vocal for Mel; (2) a sped-up honky tonk piano; (3) a normal speed vocal track for the Starlighters; and (4) a Billy Mat orchesrral track, which appears to be at normal speed. The engineers already had their hands full with two sped-up tracks that didn’t seem to precisely match up, complicated by trying to fit in the Starlighters’ vocal in the proper places, although their tempo also does not appear o be a precise match-up with the other tracks, and Billy May’s orchestra seems to have been called upon to serve as the glue to unify these disparate parts and make them sound as if they are all keeping to one master tempo. With everything going on (and believe me, there are some artifacts where extra notes or beats seem to slip in in odd places), I don’t think they’d have dared speed up Billy’s track, for fear of throwing the whole session out of whack. So Billy appears to play over the top of all the other tracks, as lickity-split as his baton and musicians will allow, and manages to somehow survive the date. Add to this the fact that Mel in vocal sessions was known to call for voices to be sped up to such-and-such “RPM”, and it’s possible that all these tracks may have been recorded on separate acetate discs, rather than magnetic tape! It’s enough to make anyone who’s ever manned an engineer’s booth nightmares.