EDITOR’S NOTE: Today, I’m happy to welcome my colleague, Fleischer historian G. Michael Dobbs, to the pages of Cartoon Research. This post (the first of many I hope) originally appeared on Facebook last week, but I felt needed to be placed here for posterity, and would be much appreciated by our dedicated readers. – Jerry Beck

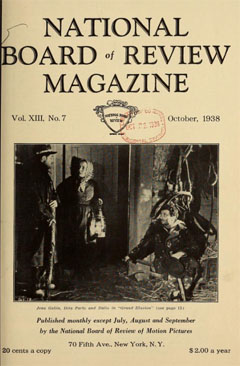

In the October 1938 edition of the National Board of Review magazine published a transcript of “an instructional talk” about the medium by Fleischer animator Thomas Moore and voice and story artist Jack Mercer, described as the studio’s “director of dialog,” to the listeners of WNYC in New York City.

In an industry where generally the only people who received press attention were the producers, it’s refreshing to see these two talented men have a bit of the spotlight, even if it reads like a comedy routine at times.

In an industry where generally the only people who received press attention were the producers, it’s refreshing to see these two talented men have a bit of the spotlight, even if it reads like a comedy routine at times.

The announcer prefaced the interview by saying, “if any of you imagine that an animator is an instrument for registering electrical discharges, Mr. Moore will put you right and give a real account of the importance of an animator’s work in the drawing and painting of a cartoon. Mr. Mercer hasn’t much to say about this side of cartoon making, but he’s going to show you who behind the strange sounds and chatter that accompany the characters in a cartoon.”

Mercer: Mr. Announcer, this might be a little irregular, but I wonder if you would do me a favor by allowing me to be the interviewer this evening. I’ve always wanted to put Mr. Moore on the spot.

Announcer: Surely, go ahead, the mic is yours.

Mercer: Good evening, Mr. Moore.

Moore: Hello Jack, what are you doing here?

Mercer: I’m going to be the interviewer so just assume that I know nothing at all about the making of cartoons.

Moore: What do you mean – assume?

Mercer: I walked into that. Well, on with the interview. I’m sure everyone is interested in animated cartoons. Will you give us something of a history?

Moore: Thomas Edison experimented with the idea of animated drawings as early as 1900, but the first man to make an animated cartoon film was the great cartoonist Windsor (sic) McCay. The idea struck him as he observed his young son flipping the pages of a book of ‘Magic Pictures.’ After many months of extensive study, he made an animated version of his cartoon strip, ‘Little Nemo in Slumberland.’ But he considered this film only an experiment and in 1909, two years after his first attempt, he made the first film for exhibition, ‘Gertie the Dinosaur.” Prior to 1922 most animated cartoons were made with paper cutouts and were pretty crude.

Mercer: You mean sorta like cutting out paper dolls, eh?

Moore: Yes exactly, you should know. The drawings of the characters in different positions were cut out and pasted over a simple background and then photographed in sequence. But since that time many improvements have been made so that today we have the full-length cartoon.

Mercer: A great many people seem to think that the full-length cartoon involves a different and more complicated process of production.

Moore: The only real difference is a matter of length, the feature being much longer permits the story to be told with more finesse and detail. The average short requires about 10,000 drawings and takes approximately seven minutes to be shown on the screen, while the full-length feature requires more than a quarter-million drawings and runs over an hour.

Mercer: There certainly has been a great advance made in the industry. Why don’t you tell out listeners how the work on a modern cartoon begins?

Moore: Gladly, the modern studio is a beehive of activity, highly systemized.

Mercer: In simple language you mean they do a lot of work.

Moore: it takes over 230 artists and technicians at least 10 weeks to prepare the drawings, which make up an animated move cartoon. Work on the cartoon begins when the musical director and the scenario writers call into conference a few of the head artist animators (Mercer, ad lib: Tell’ em I’m in the Story Department). They discuss the general lines of the plot and principal gags. The music which is to be adapted to the plot is selected. By the way Jack you are in the Story Department. I’m sure you could explain just how your department functions.

Mercer: Huh? Oh. To be sure. To be sure. Well the first thing we do is try to get an idea or facsimile –

Moore: (taking up) And after getting the idea of a synopsis, the story men write a script in complete form for the animators. In order to do this they must know all of the cartoon characters intimately – how they think and how they react. They must know the limitations imposed upon them by the censors by the audiences and by the technicalities of production. In other words, a certain subject might be condoned by one country and barred by another. One community might be flattered by an incident that would insult the next. You may like picture that I thought dull and boring. So if the script can please some of the people part of the time then the job is well done.

Mercer: Then the story goes to the Animation Department and that’s how we write stories.

Moore: Very good Jack. The head animator upon receiving the new story visualizes the picture and roughly lays it out illustrating each scene. He then calls his group together for a conference when through analysis and discussion they try to get into the mood of the story. The scenes are then divided amongst the group and they start to work. And that is where the fun begins. If you unexpectedly walked into a group of animators at work you would probably be amazed at what you saw. For the chances are, you would find one chap standing in front of a full-size mirror gesticulating wildly and making horrible faces at himself. Another on roller skates in the center of the room would be trying to act like Olive Oyl while a couple of his colleagues offer helpful suggestions such as: “Tom try that fall again, only this time throw your feet higher so that when you land your weight is more concentrated in one spot. We want to see how high you bounce.” The survivors then sit at their desks and attempt to draw on paper what they saw. An animator never knows what he may be called on to draw next. It might range from a pygmy wedding ceremony to a Giant baseball game.

Moore: Very good Jack. The head animator upon receiving the new story visualizes the picture and roughly lays it out illustrating each scene. He then calls his group together for a conference when through analysis and discussion they try to get into the mood of the story. The scenes are then divided amongst the group and they start to work. And that is where the fun begins. If you unexpectedly walked into a group of animators at work you would probably be amazed at what you saw. For the chances are, you would find one chap standing in front of a full-size mirror gesticulating wildly and making horrible faces at himself. Another on roller skates in the center of the room would be trying to act like Olive Oyl while a couple of his colleagues offer helpful suggestions such as: “Tom try that fall again, only this time throw your feet higher so that when you land your weight is more concentrated in one spot. We want to see how high you bounce.” The survivors then sit at their desks and attempt to draw on paper what they saw. An animator never knows what he may be called on to draw next. It might range from a pygmy wedding ceremony to a Giant baseball game.

Mercer: Personally I’m a Brooklyn fan.

Moore: You would be.

Mercer: I resemble that remark!

Moore: At this point I’d like to make an observation. In order to be an animator one must be slightly wacky.

Mercer: You should make a very successful animator Mr. Moore.

Moore: Thank you so much. But drawing is not the only phase of the animator’s work, for he must give complete instructions to each department as to the handling of his scene. He is director, actor, technician.

Mercer: And wacky.

Moore: The animator does not make every drawing, for that would take up too much of his time. He only makes the extremes or key drawings and then an assist or “in-betweener,” completes the scene. For instance, if he wants to animate an apple falling from a tree, he makes one drawing of the apple as it starts to fall and another at the end of the fall. The in-betweeners then make the drawings that will carry the apple from one position to the other. The animator regulates the speed of the fall by indicating the number of drawings that must be made between the two positions. When the animator starts his scene of the apple falling, he first makes a rough drawing or layout to serve as a guide to the Background Department for every action has to take place in a proper setting or location. With this guide the background artists make a detailed and carefully rendered watercolor drawing of the scene.

Moore: The animator does not make every drawing, for that would take up too much of his time. He only makes the extremes or key drawings and then an assist or “in-betweener,” completes the scene. For instance, if he wants to animate an apple falling from a tree, he makes one drawing of the apple as it starts to fall and another at the end of the fall. The in-betweeners then make the drawings that will carry the apple from one position to the other. The animator regulates the speed of the fall by indicating the number of drawings that must be made between the two positions. When the animator starts his scene of the apple falling, he first makes a rough drawing or layout to serve as a guide to the Background Department for every action has to take place in a proper setting or location. With this guide the background artists make a detailed and carefully rendered watercolor drawing of the scene.

Mercer: And that completes the work on the picture.

Moore: No, the picture is far from being completed after the animators have done their job and an enormous volume of technical work is necessary before the shooting or photography can take place. In the Inking Department, each drawing is traced on transparent celluloids. This work plays a very important part in the general scheme of preparing for the camera.

Mercer: Oh, then the drawings are ready for photographing?

Moore: No the Coloring Department now receives the celluloids together with the corresponding animator’s drawings. The Colorers or Opaquers fill in all the blank spaces between the ink lines with paint of various shades. All colors and shades are sued for the purpose. This process is highly technical and the task is very arduous, but very important, as only a perfectly colored set of drawings will result in clear and perfect photography.

Mercer: Well how do you photograph these individual drawings so that they will appear to move?

Mercer: Well how do you photograph these individual drawings so that they will appear to move?

Moore: The photographing process or cartoons is essentially the same as in regular moving pictures. The same type of camera catches the progressive movements of the cartoon character recording each successive movement. The difference between the regular and the cartoon camera is only in the speed of the operation. When filming a regular moving picture the camera runs 90 feet of film per minute. Not so the cartoon camera where individual drawings are be photographed. The work here proceeds very slowly because of the time spent by the operator for removing the photographed drawing and then assembling and adjusting the celluloids for the next photograph. One foot of film may take a whole hour to photograph and the camera instead of photographing 90 feet a minute as in the case of the regular moving picture may take a whole day to photograph 30 feet of cartoon film.

Mercer: Now we come to the process, which plays so great a part in making moving pictures today and especially cartoons. The application of sound is called “Sound Synchronization.”

Moore: That’s right. In the spacious projection room the sound director, vocal artists and the effects men face the screen. They watch the running film harmonizing the voices and the sound effects while the picture is being projected. Microphones in effective positions in the recording room pick up and carry the sound over wires to a soundproof room, where wax and film records are made. The recording thus made is called a ‘take” and the film record is called a “sound track.” The picture is projected in the screen a second time while the wax record is “played back.” The directors now get the result of their first synchronized effort pick the flaws and make the necessary corrections for the second take to follow. This procedure may be repeated gain and again until a perfect or satisfactory “take” is accomplished, after which the played back wax record is discarded. The film “sound track” is then developed and transferred to the picture film. This is called the finished negative from which the prints are made. Any number of prints can be made from a single negative. The animated cartoon is now ready for distribution. (Pause) jack, Jack, oh Jack, wake up!

Moore: Now suppose I ask you a few questions for a change.

Mercer: Why, for sure, for sure.

Moore: Inasmuch as you are in the Sound Department as well as the Story Department, perhaps you will demonstrate for us how you make some of the sounds.

Mercer: I’d be glad to.

Moore: Then suppose you give us your interpretation of a chick.

Mercer: Chicken? Mm-mm (gives imitation)

Moore: I think that one laid an egg.

Mercer: How’s this for a cow? (gives imitation)

Moore: Mm – Strictly off the cob.

Mercer: Well, you should enjoy this one. It’s a pig that gets caught in the fence. The farmer saws into the fence and the pig is freed. (gives imitation)

Moore: The pig is very natural.

Mercer: If you don’t like those imitations, let us see what you can do.

Moore: Oh, it’s easy. Why I can imitate three different dogs.

Mercer and Moore: Ad lib.

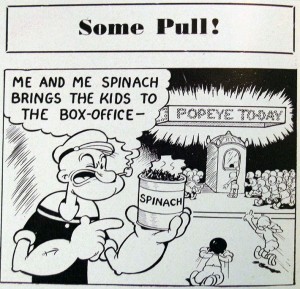

What is fascinating to me is this was carefully scripted and yet there was no mention of Max or Dave Fleischer, especially Dave’s role in the creative process. The other glaring note is at no time was it revealed that Mercer is the voice of Popeye.

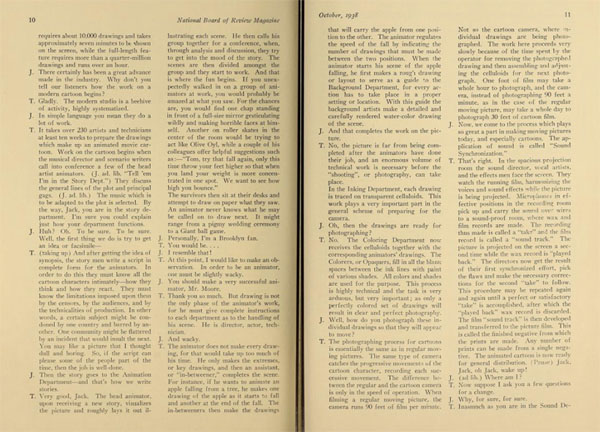

Here is the article as originally printed in the magazine. Click to enlarge:

G. Michael Dobbs is the former editor of the 1990s animation magazine Animato! and is finishing up the first volume of “Made of Pen and Ink: The Fleischer Studio Cartoons.” He works as a newspaper editor in Springfield, Massachusetts.

G. Michael Dobbs is the former editor of the 1990s animation magazine Animato! and is finishing up the first volume of “Made of Pen and Ink: The Fleischer Studio Cartoons.” He works as a newspaper editor in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Great post, GMD. looking forward to more.

The other glaring omission is any mention of all those marvelous mumblings that permeate Fleischer toons.

I know many were ad libs, but another big chunk of them must be written, especially the puns and mispronunciations. Woulda been nice to hear those details from “Popeye” himself.

Welcome aboard.

“I know many were ad libs, but another big chunk of them must be written, especially the puns and mispronunciations.”

Why must the puns in the Fleischer cartoons *necessarily* be written? I can easily imagine voice actors like Mercer making up stuff like that on the fly.

And obviously, that is why Jack Mercer ended up in the Story Department.

I thought this was a hoax at first!

“Thomas Edison experimented with the idea of animated drawings as early as 1900”

Is there any proof on this?

I suspect he’s referring to “The Enchanted Drawing” which was filmed for Edison in 1900 by the cartoonist J. Stuart Blackton. It’s arguably the first bit of animation committed to film. (Of course, Thomas Edison himself had very little to do with the films being produced under his name in 1900)

I had not known about this interview before. Thanks for posting it! 🙂

Mr Dobbs, I look forward to more of your contributions. Welcome aboard!

Thank you Jack Mercer for actually putting one of the animators into the spotlight. Tom Moore actually stayed on when Fleischer Studios became Famous Studios. He stayed at Famous through at least 1956 or 1957.

As fascinating as this piece is to read (I saw this item years ago at the Lincoln Center library while researching my voices book), we can only fervently wish that a recording of the WNYC broadcast might one day surface. It would be even better actually hearing the no doubt sly inflections of these two long-time studio colleagues. Incidentally my copy of Mike Dobbs’s long-awaited “Made of Pen and Ink: Fleischer Studios” (part 1) arrived here today, and I am looking forward to relaxing over the new year’s break with this most attractive looking book.