Suspended Animation #294

Gertie the Dinosaur might not have been officially the first animated cartoon, but it was without argument the first animated cartoon of any consequence. Its huge success should have been the springboard for happiness and good fortune for Winsor McCay and the beginning of an amazing career in animation. It wasn’t.

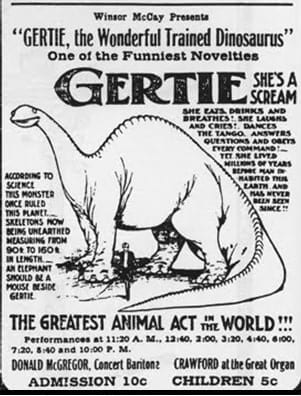

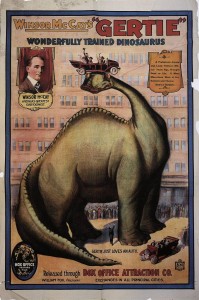

One poster proclaimed it as the “Greatest Animal Act in the World”, and went on to say: ”Gertie: she’s a scream. She eats, drinks and breathes! She laughs and cries. Dances the tango, answers questions and obeys every command! Yet, she lived millions of years before man inhabited this earth and has never been seen since!!”

One poster proclaimed it as the “Greatest Animal Act in the World”, and went on to say: ”Gertie: she’s a scream. She eats, drinks and breathes! She laughs and cries. Dances the tango, answers questions and obeys every command! Yet, she lived millions of years before man inhabited this earth and has never been seen since!!”

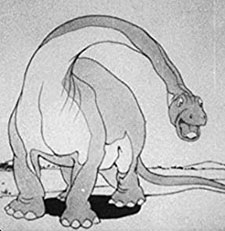

Gertie had a depth of personality. She was shy, stubborn, petulant, sensitive, playful, and curious, all within five minutes. Later animated characters of this time period were mostly interchangeable ciphers. It took Walt Disney, who had been amazed by Gertie, to reinvent the concept of personality (or character) animation to this same extent many years later.

Everyone loved the act, except for one prominent person, William Randolph Hearst, McCay’s employer, who felt that all of this theatrical nonsense was distracting McCay from his responsibilities for the Hearst papers, in particular the daily editorial cartoons. McCay never missed a deadline nor slacked in producing highly detailed and beautifully composed comics, but Hearst was known for wanting total control.

While Hearst could not legally prevent McCay from performing, he announced that any theater that booked the act would receive no advertising or mention in any Hearst newspaper, the most widely read newspapers of the time.

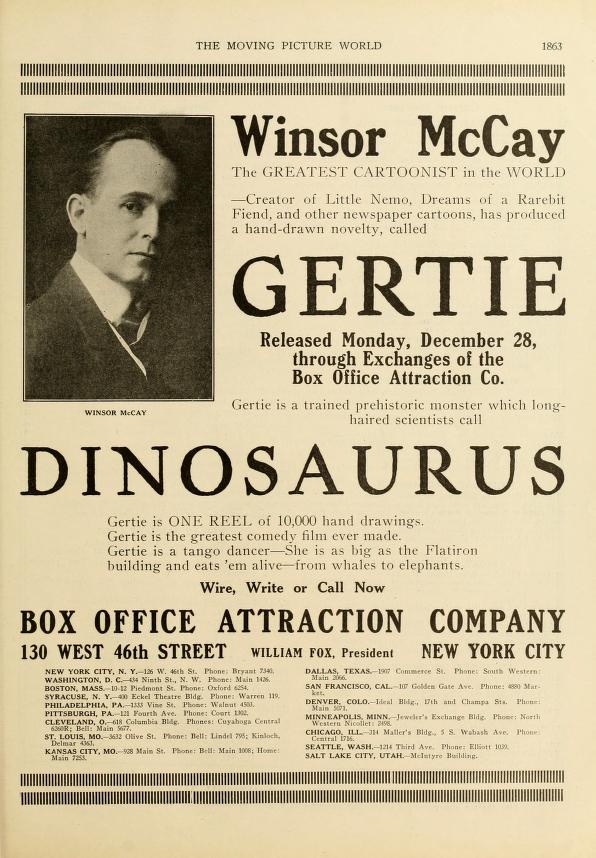

Prevented from touring with the act by theaters now afraid to book him, McCay worked with a film distributor to add a live-action prologue and epilogue for the film (more than doubling its total length by these additions). This film version of Gertie was copyrighted September 15th, 1914.

The prologue features a wager between McCay and his fellow cartoonists, including George McManus, who later became world famous for doing the popular Bringing Up Father comic strip, after the car they are in breaks down from a punctured tire in front of the American Museum of Natural History. While the tire is being changed, they go inside and see the famous dinosaur skeleton.

The film company had to receive special permission to film inside the museum and the dinosaur skeleton. They were only allowed to use natural lighting and promise that the museum would not be held up to ridicule.

McCay firmly bets a dinner for the entire group that he can bring a dinosaur to life with his drawings. Then the prologue goes on to show briefly, in an exaggerated fashion, how McCay achieved this feat, much as the prologues for his previous films had done. McCay’s young son, Robert, plays his dimwitted assistant who scatters dozens of drawings on the floor.

During the showing of the cartoon at the dinner banquet, it is interrupted by title cards containing a truncated version of McCay’s vaudeville stage dialog. Having accomplished bringing a dinosaur to life, McCay has won the bet. McManus pays the bill for the dinner.

However, a bogus cartoon, also called Gertie the Dinosaur, was released roughly a year later. It has always been assumed that it was produced by John Randolph Bray’s company because of the use of animation cels to which Bray held the patent at the time.

Bray had misrepresented himself to McCay as a writer during the production of Gertie, but stole all of McCay’s animation techniques and patented them himself. Then he sued McCay for using them.

In court, McCay easily proved he had been using those techniques for several years before Bray, and there was a settlement where McCay received royalties from Bray for those techniques for nearly two decades.

It is believed that Bray produced this film (without credits) to take advantage of the popularity of Gertie to an unsuspecting public and perhaps as a bit of revenge on McCay.

It is believed that Bray produced this film (without credits) to take advantage of the popularity of Gertie to an unsuspecting public and perhaps as a bit of revenge on McCay.

The differences between the original and the fake are obvious and significant. The background is tropical rather than prehistoric with a palm tree on the right hand side. Gertie comes out of the water as if she had been swimming underneath like a fish and onto the beach.

She is two-toned and colored gray and white rather than just white. The background in Bray’s film is static and does not contain the unintentional movement of the original that seems to resemble sun shimmering on the water and a breeze going through the leaves of the tree.

At the end of the cartoon, a woolly mammoth wanders onto the beach to get a drink of water, but a sea serpent grabs him by the trunk and a tug-of-war ensues while Gertie watches. The mammoth is able to snap his trunk away. As he walks away, Gertie picks up a rock and throws it at him to speed him along. Gertie stands up on her hind legs and laughs with two of her legs holding the sides of her stomach.

A little man in a black coat enters from the right-hand side and bows to the audience. Gertie grabs him by the back of the coat and deposits him off-screen while she bows to the audience.

Unfortunately, for many decades this misidentified film was used in documentaries to represent McCay’s much superior work. In the 1970s, Blackhawk released this as McCay’s original “made in 1909” (sic), an error in the date that pops up frequently on the internet. Tommy Stathes released a beautiful version of the fake on his Cartoon Roots: The Bray Studios blu-ray/DVD:

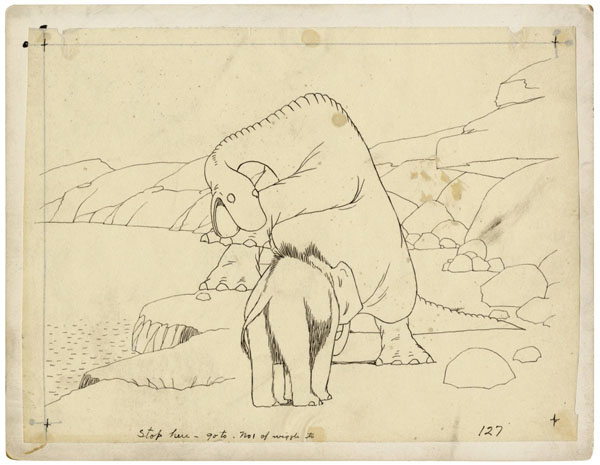

Around 1921, McCay began work on a second animated film that was to feature Gertie. Titled Gertie on Tour, it was never completed, except for less than two minutes of footage showing Gertie playing with a small toad and then with a trolley car, like a cat with a mouse, until she derails it.

Exhausted, she lies down and dreams of dancing for other dinosaurs who look exactly like her. In addition, according to notes and concept sketches, she would have bounced on the Brooklyn Bridge in New York and tried to eat the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., among other misadventures including perhaps getting stuck in a tunnel.

McCay died on July 26, 1934, of a massive cerebral hemorrhage. By that time, two decades after the release of Gertie the Dinosaur in 1914, McCay had been long-forgotten by movie audiences as an animator, since he was no longer producing new animated shorts and there was no way to view his previous accomplishments.

Twenty years later, with the help of McCay’s son Robert and Disney Legend Dick Huemer, who had seen McCay perform the act several times on stage, McCay’s original stage routine was recreated for a segment of the Disneyland television series titled “The Story of the Animated Drawing” (November 30th, 1955).

Twenty years later, with the help of McCay’s son Robert and Disney Legend Dick Huemer, who had seen McCay perform the act several times on stage, McCay’s original stage routine was recreated for a segment of the Disneyland television series titled “The Story of the Animated Drawing” (November 30th, 1955).

Huemer told animation historian Joe Adamson: “I saw McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur at the Crotona Theater in the Bronx and I was therefore able to re-create it later on a Disney television show, wherein we reenacted McCay’s performance. We didn’t have the expression back then, but if we had, I would have said “I flipped” when I first saw it.”

During the work on the segment, Walt Disney came up to Robert McCay, gestured to the Disney Studio and said, “Bob, all this should have been your father’s.”

Many of McCay’s animated shorts have been lost forever because they were filmed on highly flammable nitrate film that quickly deteriorated. Of the 10,000 drawings used to make Gertie, only 400 or so still exist in any form. Once again, thanks to the scholarship of animation historians, like John Canemaker and Donald Crafton, McCay’s work, especially Gertie, has been brought to the attention of the general public.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

I’ve seen the Gertie cartoon many times, but this is the first time I’ve seen the later version with the live-action footage. The cartoonists’ car breaks down in front of the old south entrance of the American Museum of Natural History on 77th Street; the east entrance on Central Park West that visitors use today hadn’t been built yet.

The president of the AMNH at this time was Henry Fairfield Osborn, who ran the museum from 1908 to 1933. He was born to great wealth and privilege — his father was a railroad magnate, and his “Uncle Pierpont” was banker J. P. Morgan — and people still tell stories today of his self-assured arrogance and smug sense of superiority. But he was an important palaeontologist of his time, and as head palaeontologist for the U.S. Geological Survey he led many fossil-hunting expeditions in the American West. It was Osborn who first described and named Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor, as well as other dinosaur species. Under his leadership the museum greatly expanded, transforming from a warehouse of scientific specimens to a public attraction designed to popularise the natural sciences. The dioramas, murals and mounted fossil skeletons familiar to museum goers today were all Osborn’s idea. This alienated some members of the scientific community, who had been perfectly content with the old style of “cabinet museum”.

Permission to film inside the museum could only have been granted by Osborn personally, and I doubt that any other museum director at the time would have done so. While the chance to see a living, moving dinosaur is something all palaeontologists dream about, I’m sure most of them would have balked at the idea of a Jurassic sauropod sharing screen time with a Pleistocene woolly mammoth, let along mythical beasts like dragons and sea serpents. But Osborn must have seen some value in Gertie if he was willing to open his museum to McCay’s film crew. As a scientist, Osborn espoused some theories that were antiquated even in his time; but as a populariser of science, he was very forward-thinking.

The one other prominent example of character animation after Gertie during the silent era was Otto Messmer’s Felix the Cat who Walt Disney also cited as inspiration.

Louise Beaudet and The Cinémathèque Québécoise saved McCay’s original films. Without her that material would have been lost.

I wonder if Bray’s “Diplodocus” was also shown on theaters with a live performer. There are times when the Diplodocus seems to be interacting to something offscreen. While not as great as Gertie, it’s still a charming, well-produced cartoon.

Thanks for some new details on McCay and Gertie!

The 10,000 images doesn’t hold up, though. Five minutes equals 300 seconds. If McCay drew 16 images per second as suggested in the previous post, that only adds up to 4800 drawings. Plus, you have to subtract the images that were used in cycles. And even if we suppose he drew 24 frames a second that’s still only 7200 drawings, and again you would have to subtract the recycled cels. Still a great feat! But apparently not the 10,000 he talks about. (Unless he made a lot of mistakes that never made it onto the reel!)

Also, you say ” McCay walks into the animated scene himself as a miniature caricature.” Perhaps, but I always figured that if Gertie were shown on a large screen then the animated McCay would have been the same size as the real McCay! (Or the real McCoy!)

Some of the 400 extant Gertie drawings are from a sequence that was never used in the final film. There’s also no way of telling how many drawings had to be redone. Even an artist as gifted as McCay, working in a brand new medium, was bound to make mistakes along the way; any errant drop of ink, or any line that even slightly interrupted the smooth flow of the animation, could only have been corrected by producing a new drawing from scratch. My feeling is that the figure of 10,000 drawings is, if anything, an underestimate.

400 drawings from a sequence not used in the film?! Has anyone tried to put them together to see what the sequence might have looked like?