Max Fleischer must be remembered as a mechanical genius. By the time he’d joined Bray Studios in 1916 Max had already designed and constructed a rotoscope. During the First World War he and Jacob Leventhal collaborated on advancing technical animation at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. Near the end of 1918 Fleischer and Leventhal returned to Bray Studios in New York. Whether Leventhal’s cousin Frank Goldman was already with Bray when they got back, or if he showed up soon after is unclear. He was there in March of 1919 animating on the scientific short film COMETS as F. Lyle Goldman.

Max Fleischer must be remembered as a mechanical genius. By the time he’d joined Bray Studios in 1916 Max had already designed and constructed a rotoscope. During the First World War he and Jacob Leventhal collaborated on advancing technical animation at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. Near the end of 1918 Fleischer and Leventhal returned to Bray Studios in New York. Whether Leventhal’s cousin Frank Goldman was already with Bray when they got back, or if he showed up soon after is unclear. He was there in March of 1919 animating on the scientific short film COMETS as F. Lyle Goldman.

Frank Goldman

Most of the New York animators, Paul Terry, Bill Nolan, the lot of them, focused on the entertainment aspect. Max Fleischer and Jacob Leventhal were deeply involved in technical animation for educational and training films. They worked directly with the government and private corporations on ushering in a wider understanding and acceptance of scientific advancements. Frank Goldman was right there beside them.

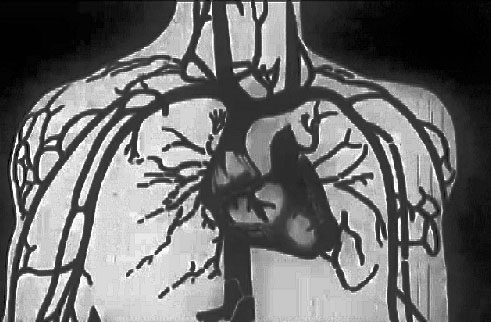

Goldman excelled at representing biological functions of the human body. Max Fleisher came to rely on him.

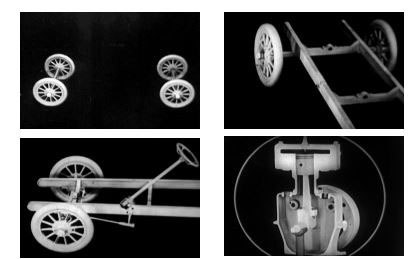

Mechanical devices were also part of Goldman’s routine, and he used stop-motion to demonstrate the nuts and-bolts of automobile engineering.

All went well at Bray Studios until 1920 when Sam Goldwyn bought an interest and upset the applecart. Max Fleischer’s renaissance clique got restless. In May of 1920 a Frank Goldman is named as v.p. of Yellowstone Productions, soon to open at a converted skating pavilion in Denver, Colorado. Yellowstone was installing a modern film lab, and that would have appealed to our Frank Goldman. He’s not named in subsequent Yellowstone articles.

In March of 1921 Bray Studios had “young scientist” Arthur Carpenter arrange microscopic film of insects for an educational short. This guy had wide-ranging credentials. Arthur Carpenter had been an officer in the Army’s Chemical Warfare Service, then a photographer for the Massachusetts State Psychopathic Hospital, and a participant in the excavation of Mayan ruins for Harvard University. Currently, he managed production of color film processing for Prizma.

Bray Studios began losing top personnel in May when Max Fleischer and Jacob Leventhal went off to start Out of the Inkwell Productions. November of 1922 saw the incorporation of Carpenter-Goldman Laboratories.

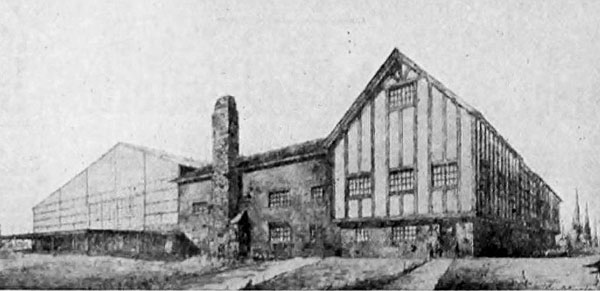

Arthur and Frank combined forces to perfect a color process that could be applied to scientific films and animation. A company called Associated Screen News had taken over the old Gaumont studio in Flushing, Queens. Carpenter-Goldman Labs became tenants there in February of 1923.

To pay the bills they processed film stock. In 1924 Carpenter-Goldman stop-motion animated GETTING TOGETHER, a film for AT&T where a telephone assembles itself. AT&T was then affiliated with Western Electric, a company very much involved in the race to perfect a system for putting sound on movies. Max Fleischer was deeply immersed in the same quest through Red Seal Pictures, while Jacob Leventhal sought a viable 3-D system. Both Carpenter and Goldman were members of the SMPE (Society of Motion Picture Engineers). They also sat on a committee to promote films as a learning tool, headed by producer William

Fox.

All these activities brought Joseph W. Coffman into the fold, sharing their interest in film as an educational medium. Joe Coffman had experience in commercial film as manager of an Atlanta, Georgia studio, and as Supervisor of Visual Education in Georgia and Alabama schools.

All these activities brought Joseph W. Coffman into the fold, sharing their interest in film as an educational medium. Joe Coffman had experience in commercial film as manager of an Atlanta, Georgia studio, and as Supervisor of Visual Education in Georgia and Alabama schools.

Coffman made his way to New York and joined SMPE. ArthurCarpenter, not one to gather moss, spent considerable time in the field doing research and photography. Around 1925 Frank Goldman brought Joe Coffman aboard to help with the workload.

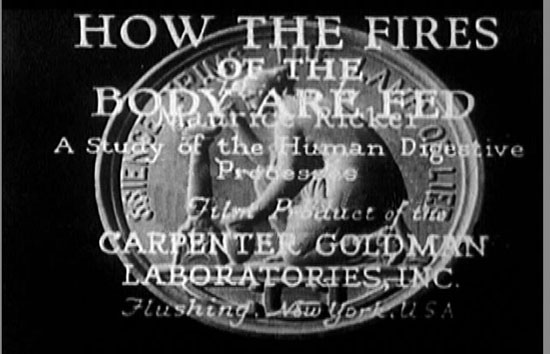

Coffman may have arranged the deal for TOMMY’S TROUBLES, an animation commissioned by Tennessee’s State Dental Association. Carpenter-Goldman Labs animated on SPEEDING UP OUR DEEP SEA CABLES for producer Charles W. Barrell. In 1926 Carpenter-Goldman made HOW THE FIRES OF THE BODY ARE FED for the U.S. Public Health Service.

Carpenter Goldman Labs relocated to the Canadian-Pacific Building at 342 Madison Avenue, across the street from the Biltmore Hotel. Several companies involved with sound engineering operated offices in the Canadian Pacific. Sound grew into a specisl interest for Joe Coffman. Art Carpenter pursued his own avenues of interest, disenchanted with being tethered to the studio. Early in 1927 Carpenter sold his interest George

Lane, a machinist who made medical films. George Lane left Goldman and Coffman to do as they did.

Being situated in Times Square was good for business. But Goldman wanted room to stretch his imagination beyond Manhattan’s safety codes. Another move brought Carpenter-Goldman Labs to 161 Harris Avenue, Long Island City. Bell Labs, a division of Western Electric, chose Carpenter-Goldman as their only outside consultants in the race to perfect sound on film.

Max Fleischer had his fortunes intertwined with radio tech whiz Lee De Forest’s attempt to market a sound synchronization system. De Forest was friends with Herman DeVry, proprietor of a vocational training school in Chicago. DeVry and the U.S. Navy cooperated on some films about electromagnetism. Carpenter-Goldman Labs got the contracts to make them.

More Naval films were requested, of a whimsical nature. These were used to boost enlistment by showing how much fun Sailor Jack and his dog Gadget had travelling to exotic ports all around the world.

The American College of Surgeons hired Carpenter-Goldman to make a series of highly technical instructional films using the Kinemacolor process. Things were not going so well for Frank’s friend Max Fleischer. Frank generously invited Max and his staff to work rent free at Harris Avenue until they were back on their

feet.

Max Fleischer’s crew operated as Inkwell Films, pounding out silent Ko-Ko the Clown cartoons. The business was switching over to sound, but Carpenter-Goldman didn’t have recording facilities. Joe Coffman worked closely with the people at Fox on a new “home” projector called the Spirograph. The August 1928 edition of Movie Maker Magazine has an article by K. R. Edwards of Kodak Teaching Films where Edwards explains that he had just animated GOLDILOCKS AND THE THREE BEARS at Carpenter-Goldman for the 16mm home projector market.

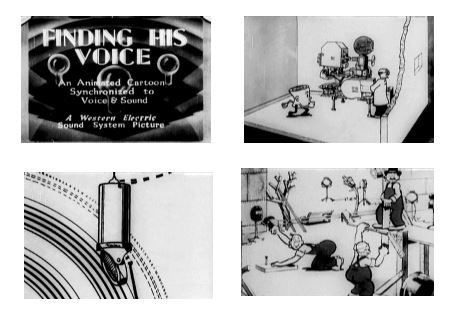

In 1929 Western Electric hired Carpenter-Goldman to make a film to be played at the dedication of each theater upon installation of Western Electric sound-on-film equipment. Goldman brought Fleischer in on it. They came up with FINDING HIS VOICE. Coffman, put in charge of sound work on the project, referred to the experience as “drawing acoustical rabbits from the hat of science”. This short cartoon is both entertaining and informative. Thirteen years later it would be included in the Museum of Modern Art’s film library.

FINDING HIS VOICE proved to be a turning point for both Fleischer and Goldman. Max left Harris Avenue to open his own studio in Times Square, making sound cartoons for Paramount Pictures. Frank was bound for the Bronx, because in September of 1929 Western Electric bought Carpenter-Goldman Labs and renamed it Audio-Cinema, Incorporated. The board of directors elected Joe Coffman president and general manager. Frank Goldman stayed on as secretary, treasurer, and production supervisor at their new headquarters: 2826 Decatur Avenue, the studio once owned by Thomas Edison.

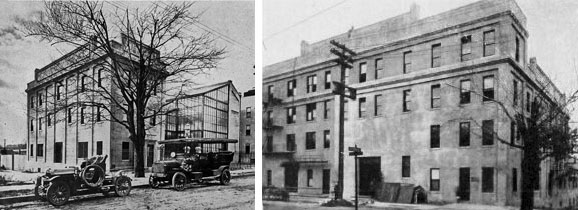

There may have been some excitement about moving into so historic an edifice. Since rising in an open Bedford Park field during 1904, a bit north of Fordham Road, the Edison Studio had racked up considerable history. Interiors for THE GREAT TRAIN ROBBERY were shot there. Raoul Barré and Bill Nolan started their animation studio there. Willis O’Brien did early stop-motion there. Edison sold the property in 1918 and it changed hands several times, being enlarged and modified. It had been around for a quarter-of-a-century when Audio-Cinema moved in while a neighborhood grew around the building, requiring the whole place to be soundproofed.

2826 Decatur Avenue in 1904 on the left; later on the right.

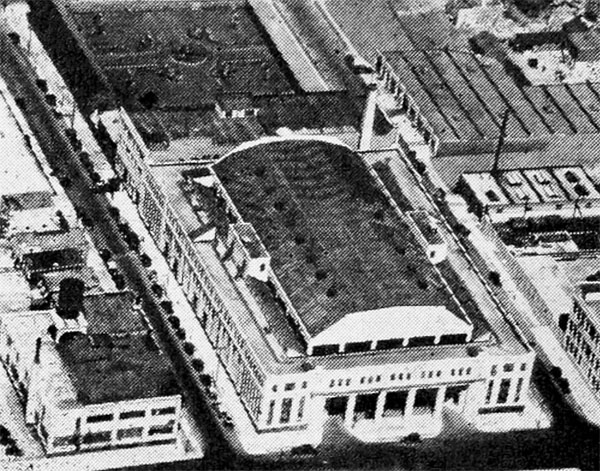

Western Electric bought a studio building Paramount Pictures vacated at 35-11 35th Avenue in Astoria, Queens. A recording engineer and an electrician, both trained at M-G-M, were hired to install Western Electric equipment. Between its two locations, Audio-Cinema was the largest East Coast studio.

Astoria

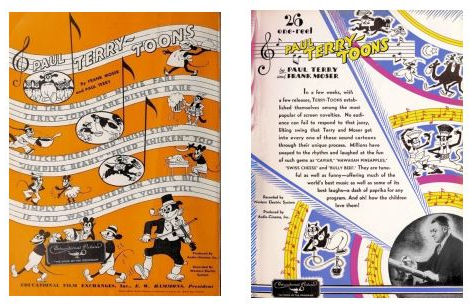

Audio-Cinema continued performing technical consultation for Bell Laboratories, extending such services to Universal Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Eastman Kodak, and Consolidated Film Industries, as well as distributing films for Mack Sennett and others. Philip Scheib, with a decade of experience as musical director for a major New York theater circuit, signed on as composer for the slate of movie shorts Audio-Cinema put into production. Paul Terry and Frank Moser, having broken off from Fables Studio, signed on to make a cartoon every two weeks.

Trade publications followed Audio-Cinema’s progress closely through 1930. Paul Terry’s animators worked at the Bronx studio and soundtracks were done in Astoria. Paul Terry and Frank Moser were listed at Audio-Cinema as Production Supervisors alongside Frank Goldman, who was also Art Director. Cy Young (spelled Sy) held the title Miniature Department Chief. Cy Young worked on Terry-Toons as an animator. Joe Coffman produced the series.

Meanwhile, Frank Goldman proceeded with cartoons of his putting out four animated ads for Aetna Life Insurance. HE KNOW BETTER concerned liability insurance. FATHER’S DAY AT was about accident insurance. A DESERT DILEMMA showed one own, AUTO HOME should always have their Aetna card in case of a car crash. THE FAMILY’S NIGHT OUT advised having home insurance against loss from burglary.

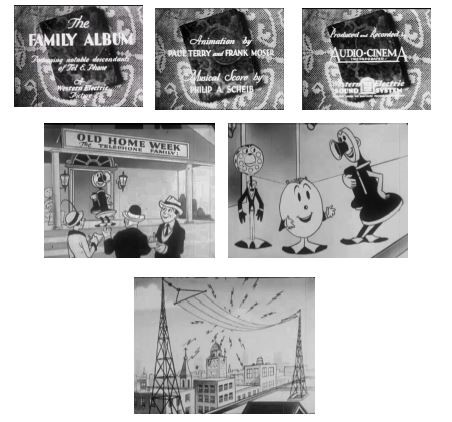

Lillian Friedman started inking Terry-Toons right out of high school. Goldman put Terry and Moser to work on A FAMILY ALBUM as a sequel to FINDING HIS VOICE.

German engineer Herman Roessle teamed with Cy Young and Lillian Friedman on MENDELSSOHN’S SPRING SONG, done in Brewster Color. Audio-Cinema made theatrical ads as well, for which Terry and Moser provided animation under Goldman’s supervision. Lillian Friedman worked with Theodore Geisel, Doctor Seuss himself, who designed character for a Flit insecticide. Warner Brothers Studio hired Audio-Cinema to do that one, possibly through Arthur Carpenter, who’d signed with Warner Brothers as a research assistant.

The Soviet Union hired Joe Coffman as sound film consultant for their state sponsored Soyuzkino. Frank Goldman continued to experiment with new technology through 1931. His latest patent application was for a combined printing and double exposure process meant to reduce animation costs. He held another patent for a three-peg page registration on animation tables.

Bill Weiss, auditor and purchasing agent for Audio-Cinema, noted there were money problems at the company. Gorge Lane was put in charge as Joe Coffman shifted from President to Chief Sound Engineer. Then Audio-Cinema just blipped out of existence.

Western Electric quickly installed their subsidiary Eastern Service Studios into the Astoria and Decatur Ave spaces, using some of the same personnel. Frank Goldman stuck around.

Joe Coffman went over to Consolidated Film Industries, the biggest film processing company in America, with six plants spread out around New York, New Jersey, Illinois, and California. Paul Terry and Frank Moser moved Terry-Toons to 203 West 140th Street, Consolidated Film’s Harlem plant, taking Phillip Scheib and Bill Weiss with them. Terry and Moser dissolved their partnership with Joseph Coffman, reincorporating without the hyphen as Terrytoons.

Audio Productions appeared in September of 1933. The Astoria studio became their base of operations, with offices in Manhattan at 250 West 57th Street, where Western Electric housed a subsidiary named Electrical Research Products, Incorporated. ERPI, as everyone called it, developed speakers for movie theaters. W. A. Bach, an ERPI trouble-shooter, was appointed as president of Audio Productions, which was actually a subsidiary of ERPI. Audio took over the Bronx and Astoria studios. Eastern Service Studios went to the old Paramount-Publix studio.

W. A. Bach was a go-getter who knew how to keep his name in the trade papers. This guy started out in Ontario, Canada with Universal Pictures’ publicity department. He helped found an association there to protect movie distributors’ rights against unscrupulous exhibitors. By 1917 Bach was running the New York publicity office for Universal. He was offered a sweet deal to organize Universal’s network of service departments across the country. During 1918 W. A. Bach used that network to monitor the influenza epidemic as a public service. He took a job assisting in the sales office of W. W. Hodkinson before going over to Famous Players Lasky to manage the booking department. That company was just building a studio in Astoria, Queens. Bach stayed on for a while as Famous Players Lasky morphed into Paramount Pictures. Consolidated Film Industries retained Bach to manage sales throughout Europe. He performed the same duties for ERPI’s Asian markets. Western Electric returned W. A. Bach to New York to oversee Audio Productions.

W. A. Bach was a go-getter who knew how to keep his name in the trade papers. This guy started out in Ontario, Canada with Universal Pictures’ publicity department. He helped found an association there to protect movie distributors’ rights against unscrupulous exhibitors. By 1917 Bach was running the New York publicity office for Universal. He was offered a sweet deal to organize Universal’s network of service departments across the country. During 1918 W. A. Bach used that network to monitor the influenza epidemic as a public service. He took a job assisting in the sales office of W. W. Hodkinson before going over to Famous Players Lasky to manage the booking department. That company was just building a studio in Astoria, Queens. Bach stayed on for a while as Famous Players Lasky morphed into Paramount Pictures. Consolidated Film Industries retained Bach to manage sales throughout Europe. He performed the same duties for ERPI’s Asian markets. Western Electric returned W. A. Bach to New York to oversee Audio Productions.

Amid this big shakeup Lillian Friedman went to Fleischer Studios, Cy Young headed for Disney, and Herman Roessle stood pat. H. L. Roberts Jr., with more than a decade of experience writing and directing industrial films, was made Animation Supervisor at Audio Productions. Frank Goldman became Director

of the Theatrical Division. Frank Speidell, an ex-journalist trained as an editor and director, was Director of the Industrial Division. Joe Coffman earned a seat on the board of directors at Consolidated Film Industries. They sent him to Hollywood in preparation for becoming a division of Republic

Pictures.

Corporations ruled the land. Frank Goldman now ran a division of a subsidiary of a subsidiary of a multi-national corporation. He’d been in the business fifteen years, helping to salvage the careers of both Max Fleischer and Paul Terry. We can thank Frank Goldman, at least in part, for Betty Boop and Mighty

Mouse. His influence on industrial animation is no less impressive.

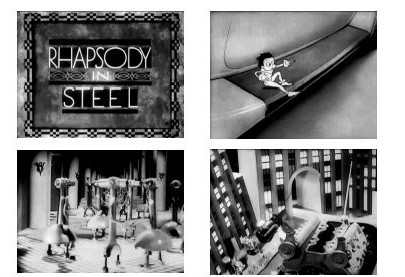

Goldman travelled to Dearborn, Michigan to make RHAPSODY IN STEEL for Ford Motors to show at the Chicago World’s Fair. Stop-motion animation for the ten minute film was done at Audio Productions’ studio. Goldman combined hand-drawn animation with the stop-motion process that had first attracted him to the business.

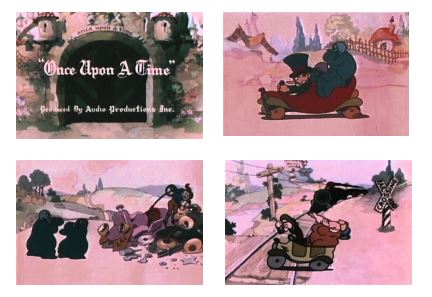

Audio Productions’ new composer Edwin Ludig scored RHAPSODY IN STEEL brilliantly. 1934 was a big year. Goldman completed ONCE UPON A TIME for Metropolitan Life Insurance then went to Hollywood to supervise Technicolor photography of it. ONCE UPON A TIME, a fairytale about traffic safety, got picked up by

public safety departments in several states and was widely screened in theaters surrounded by much publicity and fancy lobby displays. Edwin Ludig’s score was even printed as sheet music.

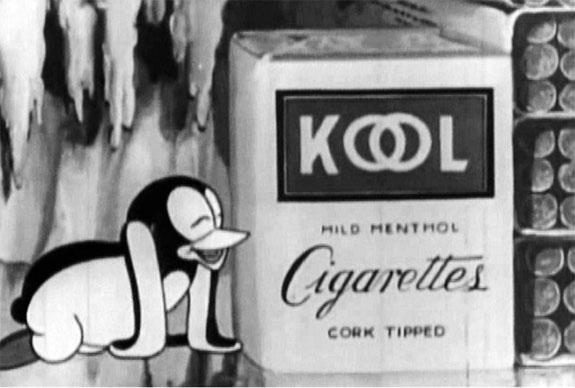

Brown & Louis Tobacco out of Kentucky had Audio Productions make an ad with a penguin for Kool cigarettes that was very well received. Audio Productions moved their headquarters from Deactur Ave to the Fox studios on 56th Street and 10th Avenue.

ERPI soon moved into the Bronx space. 1935 brought about another Kool Penguin ad, now a recognizable product mascot.

The electrical energy consortium commissioned a Reddy Killowat commercial. A British tea company requisitioned GULLIVER IN GREENFORD. Goldman directed a film for Cadillac. The State of New Jersey ordered a series of Public Service Announcements. In November of 1935 Frank Goldman resigned to take a job in Detroit with the Jam Handy Organization.

Audio Productions promoted H. L. Roberts to Creative Director. W. A. Bach traveled to England in regards to marketing animated MUSICAL MOODS. Western Electric made Bach Managing Director of their London branch. Frank Speidell was named President of Audio Productions.

Goldman’s considerable talent was put to good use in Detroit. He may have known Jamison Handy back when they were both with Bray Studios. The Jam Handy Organization had been around under another name since then. Now it made a big push with General Motors as a newly signed client. Goldman jumped in with a cartoon about Nicky Nome to be screened at General Motors conventions and limited theatrical release. Nicky Nome would star in several more colorful adventures over the next few years.

Nicky Nome

By 1940 Frank Goldman was in charge of Cartoon Animation at Jam Handy, with Rockwell Barnes running Technical Animation. Rocky Barnes had been in Chicago directing animation with Waterson Rathacker before making military training films for the

First World War. Barnes joined Jamison Handy’s crew early as Art Director, and is credited with the slogan “The difficult can be done right away. The impossible takes a little longer.”

Audio Productions carried on without Frank Goldman. In 1940 H. L. Roberts was gone too, acting as vice president of the Philadelphia=based De Frenes & Co’s NYC division. Herman Roessle was Audio’s Production Manager. They soon made Roessle a v.p. and he was with Audio Productions for the rest of his life.

Frank Speidell held the presidency of both Audio Productions and

Eastern Service Studio. It was a beehive.

But the Jam Handy Organization proved busier yet. JHO earned more annually than any other studio. In 1941 Jam Handy made DRAWING ACCOUNT – about an industrial studio executive showing a salesman how animated films can boost sales by taking him through the process.

Max Fleischer arrived to work at JHO in 1942, fresh out of Miami. It seems whenever Max lost one of his studios, Frank Goldman was there console him. Jamison Handy put his studio into training film mode as the Second World War pulled America in. Fleischer and Goldman contributed to some seriously classified

projects.

Right before Western Electric sold the Astoria studio to the U.S. Army in 1942, for use as a Signal Corps animation shop, Frank Speidell gathered investors to buy Audio Productions. Speidell moved Audio Productions into the Film Center Building at 630 Ninth Avenue, where they would remain active for decades.

Western Electric finished its ERPI research and sold 2628 Decatur Avenue as well. That Bronx studio passed through numerous hands. Occasionally someone proposed declaring it a landmark. A sizeable apartment building occupies the site today.

After the war Max Fleischer spent more-and-more time in New York. Frank Goldman was all in at Jam Handy, refining his stop-motion techniques. Goldman’s signature piece came about in 1948 as square-dancing Lucky Strike cigarettes promenaded around a barn yard.

Frank Goldman would largely be remembered for his stop-motion in films such as 1956’s ALUMINUM ON PARADE.

Francis Lyle Goldman came into the world nearly two years before the motion picture camera. When Goldman was twelve the newly built Edison Studio fiddled with bits of stop-motion. Growing up in an exchange town, Goldman may have seen those films in some St. Louis nickelodeon, unaware that he would someday supervise animation at that Bronx facility. Goldman was eighteen years old when Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo film paved

the way for an industry. Goldman entered that industry at Bray Studios when he was twenty-five, remaining relevant for half a century. Around 1968 Frank Goldman retired from the Jam Handy Org.

Frank was ten years old when the Wright Brothers flew the first airplane. As he retired human beings were about to set foot on the moon. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY ushered in the age of computers as part of animation. Frank Goldman’s role in getting to that point is difficult to calculate. He passed away near Portland, Oregon on May 12th, 1983.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

Glad to have you back, Bob. It’s fascinating to see how Frank Goldman’s career provides a common thread linking all those odds and ends of early animation like “Mendelssohn’s Spring Song”, “Once Upon a Time”, and “Kool Penguins”, not to mention the Fleischer and Terry studios.

In those Carpenter-Goldman Naval films, “Sailor Jack” and his dog are very similar to the Cracker Jack logo, which was already a registered trademark. But I guess that sort of thing was just par for the course in animation at this time.

Incredible research Bob, you have brought Goldman’s role s as an unsung hero of animation alive!

This article made me curious about the Edison Studio building at 2826 Decatur Avenue in the Bronx, since so much important film history took place there. I found out that interiors for D. W. Griffith’s last film, “The Struggle”, were shot entirely within its walls. It was the box office failure of this film that led to Audio Cinema “blipping” out of existence.

A 1945 issue of American Cinematographer magazine printed the same photo of the Edison Studio building that appears in this article — or rather, a mirror image of it. Clearly one of them has been reversed. In the photo here, the vehicles in front of the building are parked with their right sides against the curb, as one would normally do in a country like the United States where people drive on the right. In the magazine photo, the vehicles are facing the other way. If that’s correct, maybe Decatur Avenue was a one-way street, or parking restrictions were more lax in 1904. (As far as that goes, are you sure that’s the correct year? I don’t know much about cars, but I went to the Henry Ford Museum every year when I was growing up, and those designs look pretty advanced for 1904.) American Cinematographer magazine credits the photo to the Museum of Modern Art Film Library, which presumably still has the original in its files. What was your source for the image?

I got the photo from that article. I flipped it, based on other pics. Jerry wrote the caption. Try sending the photo to a car museum. The other shot is 1929.

Hi, Robert! I am very pleased with the details you dug up on Frank Goldman. As you know from our exchanges, I knew Frank late in life when he was still at Jam Handy 55 years ago. Thanks to you and Jon Bocshen, Frank’s name is being brought forward after years of obscurity. While I had been talking about him for decades, I didn’t have access to all of the material you have discovered. One important detail which I covered in my book, THE ART AND INVENTIONS OF MAX FLEISCHER: AMERICAN ANIMATION PIONEER is that Frank was the inventor of the three-hole animation punch system.

A point of correction about Max coming to Carpenter-Goldman Labs is that they were not making OUT OF THE INKWELL films, now known as THE INKWELL IMPS at this time. Max and Dave left some time in 1928 when they discovered that Alfred Weiss was cheating them, and Weiss finished the last eight films in the series for Paramount without the Fleischer Brothers. This explains the on screen absence of Max in the last entries.

Max and Dave formed Fleischer Studios, Inc. after leaving Weiss, and Frank gave Max space for as long as he wanted in order to get the company going. They were there for 10 months. During this period Max’s new company produced a revival of the Bouncing Ball Song films for Paramount, renamed SCREEN SONGS. The first was was SIDEWALKS OF NEW YORK and was seen playing on Broadway in September 1928, seen by Walt Disney prior to his recording the soundtrack for STEAMBOAT WILLIE. SIDEWALKS did not go into its official release until February 5, 1929, which is the Copyright date. By this time Fleischer Studios was going forward, producing animated theatrical and industrial films, the most famous being FINDING HIS VOICE. And following the dissolving of Out of the Inkwell Films, Inc. which filed for Bankruptcy in January 1929, Fleischer Studios moved into their former quarters in The Studebaker Building, a.k.a. 1600 Broadway and remained their for the next nine years.

Hello Ray, Your mention that you knew Frank Goldman while he still worked at Jam Handy. The reason this interests me is that my husband and I purchased and live in the home that Frank and his family built and lived in while he worked at Jam Handy. He is still remembered here in town as a someone who was the nice man who provided films for residents to watch in the community center. Imagine that! We love living here in their former home and I like imagining what it was like back then.

It sits in the far NW corner of our Township and I happen to be the Township Clerk. I am gathering information about Mr Goldman and his family to make the case that this home and property should be listed on the Historic Register so that developers do not tear it down in the future.

If you have any information that I can add to my research, or if you are willing to be interviewed as someone who personally knew him, it would go a long way in getting approval. While reading this article I wonder if he was acquainted with any of the Dodge – Wilson family, one of whom worked on or in the film industry (how I do not recall.) I am also curious as to how he ended up in Portland and whatever happened to his wife. I wonder if she passed away before he left Michigan.

Bob, Another great post! Thank you!