Donald Duck in Close-Up #7

From the time of his first starring role in 1937 through the end of Walt Disney’s life in 1966, Donald Duck starred in more than 120 theatrical shorts—and that’s not counting the dozens of other shorts in which he played supporting roles; nor the special, educational and public-service shorts, or the five feature-length films, or the numerous television programs in which he also appeared. With such a voluminous output, it’s hardly surprising that some of his films are better remembered than others. Apart from the textbook classics, there are scores of Donald Duck short cartoons that are scarcely remembered today, but are worthy of a closer look.

From the time of his first starring role in 1937 through the end of Walt Disney’s life in 1966, Donald Duck starred in more than 120 theatrical shorts—and that’s not counting the dozens of other shorts in which he played supporting roles; nor the special, educational and public-service shorts, or the five feature-length films, or the numerous television programs in which he also appeared. With such a voluminous output, it’s hardly surprising that some of his films are better remembered than others. Apart from the textbook classics, there are scores of Donald Duck short cartoons that are scarcely remembered today, but are worthy of a closer look.

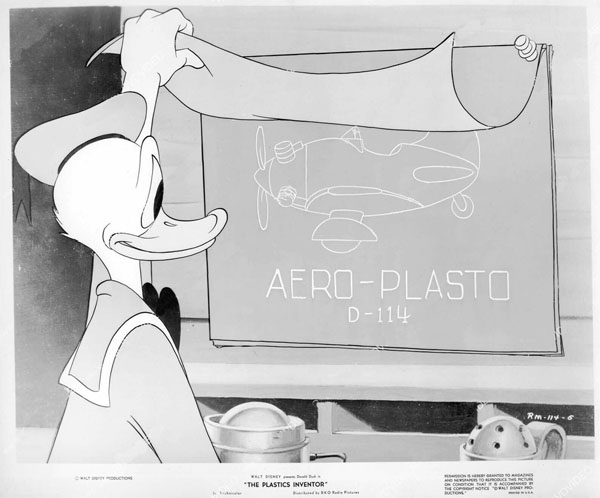

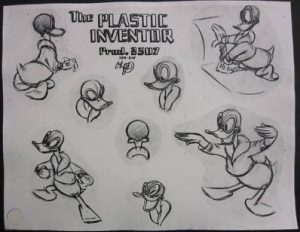

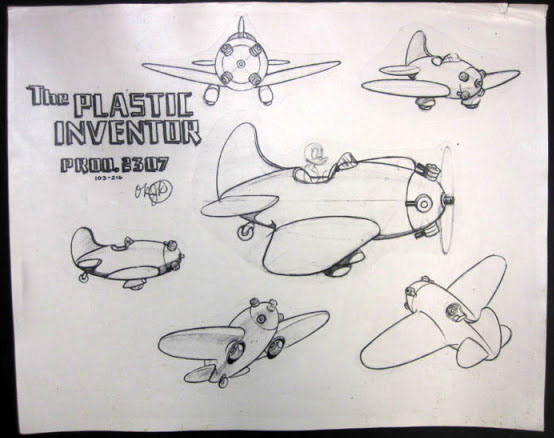

Released in the autumn of 1944, The Plastics Inventor is an unassuming entry in the Duck series. In fact, however, it’s not only an entertaining and well-made cartoon, it also has several unusual points of historical interest. To begin with, production of this film was linked to one of the educational spreads Disney was concurrently producing for LOOK magazine (recently discussed in this space). An illustrated lecture on “Plastics,” featuring Donald, appeared in the magazine’s pages in June 1944, and a scant three months later The Plastics Inventor appeared on theater screens, playing the whole idea of “baking” plastic objects for laughs. Synergy aside, the making of this film may well have preceded the idea of the magazine feature. (Story work on The Plastics Inventor started as early as February 1942, when Carl Barks was still at the Disney studio and an integral part of the Donald Duck story crew.)

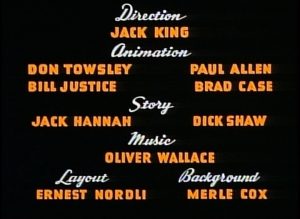

Also of interest, The Plastics Inventor features production credits on screen. This was a significant development. The earliest Disney sound cartoons had offered screen credits, and in fact the first Silly Symphonies had explicitly credited both animator Ub Iwerks and musician Carl Stalling. But when Iwerks and Stalling both quit the Disney studio on the same day in January 1930, lured away by Pat Powers, company policy was changed and screen credits abruptly disappeared from the studio’s films. Subsequent cartoons were “A Walt Disney Production,” period. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and succeeding feature-length pictures, did include extensive screen credits — so extensive that critics commented on the surfeit of names on the screen. But animators and other artists on Disney shorts remained unsung well into the 1940s. Now, in 1944, screen credits were quietly reinstated. The Plastics Inventor became Donald’s first adventure to identify some of the artists onscreen.

Also of interest, The Plastics Inventor features production credits on screen. This was a significant development. The earliest Disney sound cartoons had offered screen credits, and in fact the first Silly Symphonies had explicitly credited both animator Ub Iwerks and musician Carl Stalling. But when Iwerks and Stalling both quit the Disney studio on the same day in January 1930, lured away by Pat Powers, company policy was changed and screen credits abruptly disappeared from the studio’s films. Subsequent cartoons were “A Walt Disney Production,” period. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and succeeding feature-length pictures, did include extensive screen credits — so extensive that critics commented on the surfeit of names on the screen. But animators and other artists on Disney shorts remained unsung well into the 1940s. Now, in 1944, screen credits were quietly reinstated. The Plastics Inventor became Donald’s first adventure to identify some of the artists onscreen.

And, in fact, the animation credits in this film offer an intriguing mystery of their own. The format seen here would become the standard protocol for animation credits in Disney shorts: four names — three character animators and one effects animator. This time, however, there’s a strange anomaly. The effects animator credited here is Brad Case — and in the film’s final draft, reflected in the credit list below, there’s no mention of Brad Case! Instead, effects work is assigned to two other well-known members of the department: Ed Aardal and the legendary Josh Meador. The draft is dated March 1944, and it’s entirely possible that some shakeup during production, after that date, led to the recasting of the effects scenes. If such a shakeup did occur, the film’s exposure sheets would likely shed some light on it. However, at this writing I have not been able to review the Plastics Inventor exposure sheets. If and when I discover the solution to this mystery, I’ll post my report here!

2307

Released 1 September 1944 by RKO Radio

MPPDA certificate 9842

Director: Jack King

Music: Ollie Wallace

Story: Jack Hannah, Dick Shaw

Layout: Ernie Nordli

Backgrounds: Merle Cox

Animation: Bill Justice (Duck listens to radio, assembles junk, throws it into pot and stirs it;

beginning of Duck’s flight; plane climbs and dives, speedometer breaks; plane in profile dives and comes apart, towing Duck behind it; Duck parachutes to ground and lands in “pie,” blackbirds fly out, angry Duck hears announcer’s last comments)

• Harvey Toombs (Duck dips paddle in plastic, swings pot over and dumps it into mold)

• Judge Whitaker (Duck looks at blueprints, ties on apron; Duck opens mold, removes plane and catches it on finger; Duck hurriedly makes helmet; plane starts to melt and Duck tries to restore nose, wings, and wheels)

• Paul Allen (Duck mixes and rolls plastic, collects stampers, stamps parts and puts them in oven; helmet starts to melt into pigtails)

• Don Towsley (Duck sniffs and removes tail assembly from toaster, tests cogwheel with straw; Duck starts to “black out,” recovers and climbs; Duck listens to radio as rainstorm starts and continues flight; Duck back into cockpit and tries to apply brakes and steer, plane slides over mountain peaks and wheel comes off; Duck tries to control plane as it bucks up and down and sides start to sag; Duck plays exhaust pipe like bagpipes, Duck’s legs walk down bottom of plane and stretch plastic, plane melts into parachute with Duck dangling from bottom)

• Lee Morehouse (plane winds in and out among mountains)

Efx animation: Ed Aardal (glowing radio dial through “This little number will do anything”; articles fall into pot; motor fires to rhythm)

• Josh Meador (pile of junk diminishes; comet; tree pulled by suction; radio dial beginning with “one fault”; rainstorm; radio melts in final scene)

Assistant director: Joel Greenhalgh

Unit secretary: Dessie Flynn

A third point of historical interest came to light after the film was released—eight months afterward. Charles A. Breskin apparently discovered The Plastics Inventor by accident in May 1945 when he saw it at the movies. Breskin was the editor and publisher of Modern Plastics magazine, an industry organ, and the Donald Duck cartoon moved him to indignation. His editorial in the magazine protested: “Although we realize this cartoon is intended to be humorous, the result unfortunately is to belittle plastics.… I think this picture will do incalculable harm to our industry. Even if it is a comic exaggeration, the film leaves the uninformed movie-goer with the impression that (1) plastics are easily made from junk and (2) that they melt in water. It is this kind of muddled thinking about plastics that the industry is trying to correct.” Breskin urged his readers to write letters and telegrams directly to Walt, denouncing the cartoon and demanding that he withdraw it from circulation!

Breskin did succeed in arousing the collective wrath of the plastics industry; a host of correspondents from across the nation wrote to Walt to protest The Plastics Inventor. Needless to say, their campaign was unsuccessful; the studio did not withdraw the cartoon from release. And, happily, some members of the industry did maintain their senses of humor. One correspondent, editor of a rival plastics magazine, wrote to Walt: “All of us who laughed with your jolly aviator want to join in thanking you for giving plastics a break. We don’t mind a bit that Donald Duck’s materials were junk and turned into a plane and a melting parachute, because we know that plastics are not so shaky that a little ribbing will do them any harm. Thanks from all of us for a nice boost.”

Next Month: Promoting Fun and Fancy Free

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

“I just want to say one word to you. Just one word. Are you listening? Plastics!” — Mr. McGuire (Walter Brooke), to Ben (Dustin Hoffman), in “The Graduate”

I’m reminded of the “Lie Detector” in “The Practical Pig” (1939): a new invention that most people had heard of but few had actually seen, and whose depiction in the cartoon bears no resemblance whatsoever to the actual device. By 1944 plastics must have been familiar enough to the general public, but so poorly understood, that the idea that a hobbyist could produce them at home by boiling down old shoes in a cauldron, or that a plastic airplane could survive atmospheric re-entry but would melt on contact with water, was not yet unthinkably ridiculous. No wonder some people in the industry objected to “The Plastics Inventor”. On the other hand, as the Look magazine piece suggests, industry leaders were already predicting that plastics would someday replace glass, metal, wood, and stone — a claim that, however prescient in hindsight, many people at the time would have regarded as hubris. It may be dated, but it’s still a very funny cartoon — perhaps all the funnier for being so dated!

My favourite part is the “music played with all-plastic instruments” — a vibraphone (whose bars and resonators are made of aluminium) and a guitar that sounds to me like a steel-bodied model. Plastic, for all its virtues, does not resonate well; but we can be grateful that it’s replaced ivory as the material of choice for surfacing piano keys. In any case, that tune is a real toe-tapper!

One of my favorites! One wonders what Donald could do with a 3D printer…

Make a 4th nephew: Screwy

Everyone knows the fourth nephew is Phooey!

No, that’s the Hong Kong nephew!

http://www.sullivanet.com/duckburg/phooey.htm

One of the interesting things on the credits was Disney was already running title sequence music before this long enough to fit in animation credits, but didn’t. When Wanrer’s finally went to full credits in 1945, Carl Stalling had to shorten the opening title music for “Merrily We Roll Along” and “The Merrie-Go-Round Broke Down” to make space for the expanded titles, so Warners didn’t have to shell out more $$$ for costly Technicolor footage.

That is one expansive basement Donald’s got there in his home.

The humorous narration by the Professor was a radio actor named Charles Seel. What’s of interest to me is that the opening announcer is John Dehner, who had been an assistant animator on staff at Disney’s for some time, while trying to start his stalled acting career. I believe he was moonlighting on local radio while under Walt’s employ. He can be seen in a couple of shots in THE RELUCTANT DRAGON. He finally went freelance as a radio announcer and then actor, and was highly successful throughout the late 40s and in the 50s. He did quite a few cartoon jobs for Disney and I’d love to know the exact tenure of his employment there.

Thank you for this information, Keith! Good to know. I don’t have the dates of Dehner’s Disney employment, but he does sound like a multitalented individual.

Perhaps Brad Case animated some incidental effects in other animators’ scenes, and the draft only mentions effects animators when they were the main animators of a scene?

Another notable thing about the on-screen credits is that they came along just in time for Jack Hannah to get a single “story” credit before being promoted to director.

It looks like Paul Allen was Jack King’s dance specialist, as his main contribution to this cartoon is the scenes where Donald is working in time to music, and dance-walking over to the oven.

As on “Donald’s Crime”, Lee Morehouse was only given a single shot, and this time it’s not even character animation. He was a prominent animator in Jack King’s Duck unit a few years earlier, does anyone know what happened? (I know he later got a single solitary story credit, on Jack Hannahs “Inferior Decorator”.

Thanks for these observations, John. Yes, Paul Allen does seem to specialize in dance scenes, doesn’t he? He gets the bulk of Donald’s and Daisy’s dance scenes in “Mr. Duck Steps Out” — a pretty spectacular showcase — and again in “Donald’s Crime.” Morehouse’s credits do seem to wax and wane, mostly wane, during the 1940s, but I don’t know what was happening behind the scenes.

When I was a kid in the early 50s I had plenty of plastic toys to play with but also metal hand-me-downs. At some point I started wondering just exactly what they made plastic from and asked my mother. “Oh, junk,” she said, and I believed that for a long time. But I never forgot that exchange, and always assumed it was something she just made on the spur of the moment to satisfy me. Now I’m wondering if she’d seen the cartoon or if the outraged Breskin was right!