Suspended Animation #351

Walt Disney struggled trying to make the tales of Reynard the Fox into an animated feature film.

Walt had liked the fact that Song of the South (1946) featured three animated segments that helped advance the story in the live action film. In addition, they had received the most positive recognition.

Walt had liked the fact that Song of the South (1946) featured three animated segments that helped advance the story in the live action film. In addition, they had received the most positive recognition.

So when planning Treasure Island (1950), he thought of including three animated segments for Long John Silver to tell the cabin boy Jim Hawkins. The first short would have been Reynard and the Golden Apple where even though Reynard steals the King’s golden apple, it was to protect it from the real thieves. The moral would have been that things are not always what they seem.

Later, when Jim is captured by the pirates, Silver prevents Jim from being killed by telling the story of How Reynard Saved Grimbert’s Life that suggested if the pirates killed Jim it would make their own deaths a certainty.

Finally, at the end of the film where Silver is captured, he tells the tale of Reynard’s Death and Confession to affirm that one should always use one’s wits for good not evil.

In 1956, animator Ken Anderson did some storyboards. However, he never came up with a full story and the boards just depict some scenes of Reynard on the gallows and several concept sketches for characters. At the same time, animator Bill Peet did a couple dozen concept sketches including for a fox princess, a lion king and rhinoceros guards in hooded uniforms.

Ken Anderson sketch for “Reynard”

However, Anderson did come up with a script in 1960 working with animator Marc Davis. As 101 Dalmatians (1961) was finishing up work, Walt assigned Anderson and Davis who had both made such significant contributions to the film to tackle the problem. Walt had told them both to scrap all previous material and just start fresh, an approach he would later take with The Jungle Book (1967).

Their solution was to combine the stories of Chanticleer and Reynard by making the fox the antagonist in the story and that would avoid having to twist his deceptions into something noble.

In 1960, Walt said, “Go for the fun stuff! We should really have a ball with this type of picture. The Fox represents the conniving element; he’s always misleading people. Chanticleer represents the good solid citizen. Get personalities into the minor characters. When you see a dog, you don’t need anything. But you take a rooster… you don’t feel like picking a rooster up and petting it.”

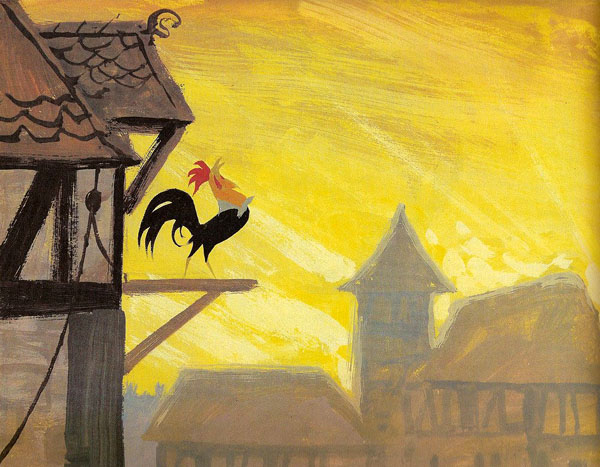

Marc Davis art for “Chanticleer”

In addition, Davis was excited about turning the film into the style of a big full-fledged Broadway musical. Davis said, “What we’re doing here is a takeoff of a musical comedy. Have your chorus line; have people setting out tables like you’d stage a musical comedy. Then Chanticleer enters (and walks through the town).”

The opening scene is Chanticleer crowing and waking up the sleepy little 1800s French farm village as it prepares for the day. In a song called Chanticleer with lyrics by Mel Leven and music by George Bruns that might remind some people of the opening song about Belle or the later song praising Gaston in Beauty and the Beast (1991), the animals sing:

“Who brings up the morning sun?

“Who makes all the chickens run?

“Who is loved by everyone?

“Chanticleer!

“Over whom do we all fuss?

“Whom does every girl discuss?

“Someone who’s so good to us

“Chanticleer!”

The song writers had composed two other songs: You No Good Reynard (sung by Reynard’s wife about how all his vaulted promises never materialized for their family: “Always clever and deceiving; Always getting caught at thieving; Always packing up and leaving; You no good Reynard!”) and Yesterday is Over (the fancy Pheasant would sing to Chanticleer to assure him that the other animals would not ostracize him).

Chanticleer was vain because he thought his crowing every morning caused the sun to come up. Despite his flaws, the farm villagers loved him as he strutted around. He was so popular that they made him the mayor which was a big mistake. He became very authorative, increasing the egg quota so that the hens worked from dawn to dusk without a break.

One morning, the sly fox Reynard who was hungry came upon the farm village. A flatterer and smooth talker, he soon discovered the town’s dissatisfaction with Chanticleer as mayor. He found that election day was soon but people were afraid not to vote for Chanticleer because the sun would not come up.

Reynard rounded up his band of night creatures (vultures, weasels, moles, cats, owls and more) and brought them into town to perform as a carnival to support his candidacy for mayor. He campaigned for “Fun! Fun! Fun!” instead of Chanticleer’s “Work! Work! Work!”

Chanticleer ignored the foolishness until he saw everyone was partying all night at the carnival and chores were left undone including egg production. Reynard brought in the infamous Senor Poco Loco, a never defeated fighting cock. A beautiful Pheasant named Henrietta constantly tried to get Chanticleer’s attention. Reynard gave her an extensive makeover that caught Chanticleer’s notice in an attempt to distract the rooster and then set her up with a date with Senor Poco Loco.

Angered and jealous, Chanticleer challenged Senor Poco Loco to a pre-dawn duel with swords. That previous night, as a party for his forthcoming victory, Reynard and his cohorts had raided the henhouse and they sat watching the event with full bellies.

Angered and jealous, Chanticleer challenged Senor Poco Loco to a pre-dawn duel with swords. That previous night, as a party for his forthcoming victory, Reynard and his cohorts had raided the henhouse and they sat watching the event with full bellies.

Despite battling bravely, Chanticleer was no match for the superior skill of Senor Poco Loco. However, much worse, while they were duelling, the sun rose without Chanticleer crowing. Sergeant, the village police dog, had discovered the destruction in the henhouse and charged in to arrest Reynard and his crew who fled to the hills never to return.

Chanticleer felt ashamed and humilated and spent the next three days in bed. The sun continued to rise but the villagers did not. Chanticleer’s crowing had been their alarm clock.

Chanticleer tried to sneak out of the village forever but was stopped and reminded by Henrietta that no one in the village is more important than anyone else. Everyone had a job to do. They must work or the village will not run but there needs to be time for play as well.

So Chanticleer continued to crow every morning to wake everyone up but he also crowed at 4:30pm in the late afternoon to remind them to stop working and go and play.

In 1961, money was once again tight at the Disney Studio especially with Walt’s elaborate plans for a new entertainment venue in Florida. His brother, Roy, even tried to convince Walt to stop all further animated feature productions because of time, labor and expense and that there were enough animated features in the vault already to constantly re-release every seven years.

In 1961, money was once again tight at the Disney Studio especially with Walt’s elaborate plans for a new entertainment venue in Florida. His brother, Roy, even tried to convince Walt to stop all further animated feature productions because of time, labor and expense and that there were enough animated features in the vault already to constantly re-release every seven years.

Walt rejected that idea but there were two animated features fairly along in development. He decided there was only enough money to make one of them. Bill Peet had developed The Sword in the Stone based on T.H. White’s story of young King Arthur and Anderson and Davis had spent a year developing Chanticleer with Reynard.

Davis remembered, “We had all the artwork up on the walls, and the money people came in like it was a funeral. They sat in the front and Walt sat at the back which was unusual. We went all the way through the presentation and met with silence. They all filed out and that was the end of it.”

In Peet’s autobiography, Peet claims that at the pitch meeting he was the one in the back of the room who yelled out, “You you can’t make a personality out a chicken!”

Walt decided it would be less expensive to make Sword in the Stone especially with its fewer characters, that it reminded him of his current favorite Broadway show Camelot, and that the story was more heartwarming and identifiable for an audience with the underdog Wart struggling to prove himself.

Davis stated, “I think that I did some of my best drawings at the studio for Chanticleer”.

In 1980, storyman and artist Mel Shaw did some pastel drawings hoping to revive the project but it met with the same disdain from those running the Disney Studio at that time.

Chanticleer by Mel Shaw

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

My understanding is that the decision to film “Treasure Island” in England was made because of the Exchange Control Act of 1947, under which the profits that Disney’s films earned in the UK could not be taken out of the country. Obviously setting up a second animation studio there was out of the question. The animation sequences with Reynard would have increased the film’s running time to at least two hours and probably doubled its costs, and the complications of budgeting half the movie in pounds sterling and the other half in U.S. dollars would have created an accounting nightmare. No wonder the plan was scrapped.

The treatment of the Chanticleer/Reynard story by Davis and Anderson sounds quite good, and I’m sorry the “money people” decided to cancel it in favour of “The Sword in the Stone”. But then, I read the story of “The Sword in the Stone” (in one of my sister’s Disney storybooks) long before I ever saw the film, so I know for a fact that it reads better on paper than it comes across on the screen.

“Sword in the Stone,” mediocre as it is, was the wiser course of action because it represented a solid, singular story (how well the film actually tells it is another discussion) whose characters belonged to it. The only way Chanticleer and Reynard could have worked together in one film was to do another “Ichabod and Mr. Toad”: a half-baked rationalization that the two characters had anything to do with each other, but at least entertaining segments.

There was a storybook that used some of the Davis art, but as I recall it didn’t seem to follow any of the scenarios described here. Simply a new tale to justify using the pictures?

Jim, any chance on an article or two about the aborted Disney feature Catfish Bend? It’s a pity that Disney never got that or Chanticleer off the ground.

I seem to have read that Walt himself was disappointed with the results of “The Sword in the Stone” which might be one of the reasons why he became a bit more involved with “The Jungle Book”. This ruffled Bill Peet’s feathers so much that he finally decided to quit and spend more time on doing children’s books.

In fact, Peet’s last book was a variation of the Chanticleer story (done in a more realistic style) called “Cock-a-Doodle-Dudley” :

http://www.billpeet.net/pages/dudley.htm