Donald Duck in Close-Up #12

As I’ve mentioned in earlier installments of this column, David Gerstein and I have been working for some time on a forthcoming major publication on Donald Duck. This has been a blessing, not least because it has afforded the opportunity for a deeper-than-ever research dive into Donald’s screen and comics career—an opportunity for a Disney nerd to pursue endless details of individual films and comic strips to his heart’s content. But along with all those countless ground-level details, the overall process has given rise to some more general thoughts on Donald Duck himself and his place in Disney and pop-culture history. I hope Cartoon Research readers won’t object if I wind up this series by indulging in some of those broader reflections—and, possibly, will consider offering some of their own.

Most of Walt Disney’s great successes had an element of chance in them, and the sudden and unexpected success of Donald Duck in 1934–37 was no exception.

Most of Walt Disney’s great successes had an element of chance in them, and the sudden and unexpected success of Donald Duck in 1934–37 was no exception.

Walt and company doubtless hoped that all their characters would find favor with audiences, but the popular response to Donald’s first appearances was far out of the ordinary. Practically overnight, the Duck was a phenomenon. This brought out a key facet of Walt Disney’s genius: the ability to seize an unexpected, serendipitous event and run with it, giving it the appearance of a strategy that had been carefully planned all along. Noting the public’s appetite for his cranky new antihero, Walt wasted no time: Donald soon began to appear in Disney comic strips and storybooks. His rise to prominence on the movie screen was particularly notable. Introduced as a supporting character in 1934, Donald was headlining in his own starring series within three years.

(And, in fact, he might have attained this career milestone even earlier if not for contractual obligations. Disney’s early distribution contracts called for specific quantities of Mickey Mouse and Silly Symphony cartoons, a rigid guideline that didn’t allow for new variations. Irrepressible Donald refused to be constrained by such regulations, and was seen in 1936–37 starring in several shorts that were “Mickey Mouse” cartoons in name only. Finally Disney’s new distribution contract with RKO, taking effect in 1937, allowed a new flexibility that made possible an official Donald Duck starring series, and the Duck was off and waddling.)

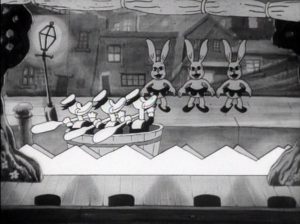

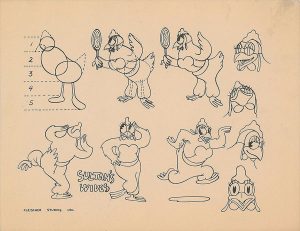

Once launched on his stellar trajectory, Donald was unstoppable. It has often been observed that Donald’s star power threatened to eclipse that of Mickey Mouse, and in fact he did ultimately star in a far greater number of films than Mickey did, despite the latter’s six-year head start. This brings an obvious question to mind. Mickey’s own rise to fame in 1928–1930 had been equally remarkable, and his success had produced a flood of imitations. Within a year or two, nearly every other cartoon studio had introduced its own character or characters in frank imitation of Mickey. Some of the imitations were more blatant than others; our friend Steve Stanchfield has recently shared one of the more brazen ripoffs here on Cartoon Research. As historically fascinating as some of these appropriations were, they didn’t last long, and the genuine Mickey Mouse asserted his preeminence over the pretenders from other studios. But this chapter in Mickey’s success story begs the question: Donald Duck enjoyed a spectacular success story of his own in the mid-1930s; why weren’t there a legion of Donald imitations?It wasn’t for lack of effort. Those other cartoon studios remained alert to the latest Disney innovations, and soon after Donald’s debut, some of them began to take notice. In October 1934, a scant two months after Orphans’ Benefit, Warner Bros. released Shake Your Powder Puff, a Merrie Melodie directed by Friz Freleng, which included a trio of singing ducks in sailor suits, looking very much like Donald’s then-current model. But apart from such superficial costuming similarities, Donald quickly proved inimitable. Ducks continued to turn up in other studios’ cartoons, but the producers implicitly acknowledged the impossibility of trying to duplicate Donald’s personality or voice. Fleischer’s Chicken a la King (1936) featured a seductive Mae West duck, and her boyfriend, a bold desert bandit duck, both of whom spoke in funny “duck” voices but came nowhere near Clarence Nash’s distinctive Donald voice.

The two duck personalities on display in this scene from “Who Framed Roger Rabbit” (1988)

This raises another obvious question: did Donald also have multiple personalities? I would argue that, to a certain extent, he did. Disney directors famously had less autonomy than those at the Schlesinger studio, since all were subject to Walt’s own ideas and control; but the three most prominent Disney directors of the 1930s—Wilfred Jackson, Dave Hand, and Ben Sharpsteen—had already demonstrated that a good director could inject his own voice into a Disney cartoon. Over the next two decades, the studio’s Donald Duck unit put that theory to the test. During that time the vast majority of Donald’s films were directed by one of two Jacks: Jack King, who took command of the series in 1938, and Jack Hannah, who stepped into King’s place in the mid-1940s.

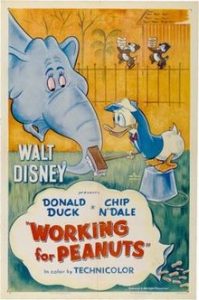

Today Hannah enjoys a loyal fan base who cherish his scores of Duck cartoons. It was Hannah who developed two mischievous chipmunks, pesky rascals in earlier films, into Chip and Dale, full-fledged characters who might serve as ongoing foils for Donald. Hannah was fond of picturing Donald in pitched battles (and, invariably, losing battles) against the two chipmunks and other tiny adversaries. Hannah also supervised Donald’s forays into new technology: 3-D (Working for Peanuts) and television (“The Donald Duck Story,” the fourth episode in the premiere season of Disneyland, and other Duck-centric episodes).

Today Hannah enjoys a loyal fan base who cherish his scores of Duck cartoons. It was Hannah who developed two mischievous chipmunks, pesky rascals in earlier films, into Chip and Dale, full-fledged characters who might serve as ongoing foils for Donald. Hannah was fond of picturing Donald in pitched battles (and, invariably, losing battles) against the two chipmunks and other tiny adversaries. Hannah also supervised Donald’s forays into new technology: 3-D (Working for Peanuts) and television (“The Donald Duck Story,” the fourth episode in the premiere season of Disneyland, and other Duck-centric episodes).

But personally, I also have a soft spot for Jack King’s earlier efforts. We’ve observed in an earlier column that Donald’s famous temper did not entirely dominate his personality. King’s cartoons relied less on formulaic skirmishes and extracted rich comedy from other sides of Donald’s personality: his selfishness, his cowardice, his taste for mean-spirited mischief. During King’s tenure Donald tackled ambitious projects—a dog laundry, a window-cleaning business, an all-plastic airplane—inevitably with disastrous results. World War II also took place on King’s watch, and he directed Donald’s series of service comedies, revealing yet another facet of the Duck’s personality: the ordinary Joe, thrust into the armed forces alongside so many of his fellows and experiencing the drudgery of an American GI’s life. It’s also worth noting that King’s years at the helm coincided with what was, arguably, the peak of the studio’s luxurious visual style. In his cartoons, animation connoisseurs can savor the rich, full animation of Disney’s top “Duck men,” taking place before lovely watercolor backgrounds.

And of course, along with King and Hannah, other directors did sometimes contribute nuances of their own to Donald’s story. Among these were Dick Lundy, one of the aforementioned “Duck men,” who moved into the director’s chair for nine of Donald’s adventures, and Wilfred Jackson, one of the top Disney directors, who also paid an occasional visit to Donald’s world. Of particular note was the impact of Jack Kinney, who directed the classic, Academy Award-winning propaganda film Der Fuehrer’s Face. Elsewhere, Kinney’s influence steered Donald into the unlikely territory of film noir, as we’ve also noted in an earlier column.

And that’s just on the movie screen! It could be argued, and has been argued, that Donald was an entirely different duck in the comics. Here again, individual artists—Al Taliaferro in newspaper comic strips, and Carl Barks and others in comic books—have made their own contributions to Donald’s multifaceted identity. The estimable Michael Barrier has written at length on the complexities that Barks brought to Donald’s personality in his comics. “The ducks, Donald and the nephews, were by [the early 1950s] extraordinarily mutable characters,” Barrier writes, “the nature of their relationship, as Barks depicted it, shifting from month to month, sometimes radically.” Even apart from his relationship with his nephews, Donald displayed a wide range in his personality traits. Within a single comics story he might engineer a harmful practical joke against a rival, then experience an attack of conscience—morphing from vindictive glee to repentant compassion in the space of a few comic panels.

And that’s just on the movie screen! It could be argued, and has been argued, that Donald was an entirely different duck in the comics. Here again, individual artists—Al Taliaferro in newspaper comic strips, and Carl Barks and others in comic books—have made their own contributions to Donald’s multifaceted identity. The estimable Michael Barrier has written at length on the complexities that Barks brought to Donald’s personality in his comics. “The ducks, Donald and the nephews, were by [the early 1950s] extraordinarily mutable characters,” Barrier writes, “the nature of their relationship, as Barks depicted it, shifting from month to month, sometimes radically.” Even apart from his relationship with his nephews, Donald displayed a wide range in his personality traits. Within a single comics story he might engineer a harmful practical joke against a rival, then experience an attack of conscience—morphing from vindictive glee to repentant compassion in the space of a few comic panels.

But, as Barrier also points out, these seeming contradictions actually strengthened the overall integrity of Donald’s character: “Donald in Barks’s stories is variously brave and foolish, generous and spiteful, childish and mature. … His mutations thus make him more real, not less, because they make him more like us: like Barks’s Donald, we retain some core of identity through what may be tremendous changes in everything about us and around us.”

As in the comics, one might argue, so in the movies and in Donald’s larger universe. In the long view of his career, Donald Duck is a mass of paradoxical oppositions: the pugnacious agitator who panics and flees at the first sign of real danger; the lazy pessimist who dares to dream of bigger and better things, only to have his hopes dashed once again; the foul-tempered misanthrope who becomes an effective diplomatic ambassador in Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros. And yet, somehow, all these contradictory impulses are absorbed within a character who is unmistakably Donald Duck—an instantly recognizable individual, never for a moment to be mistaken for Daffy Duck or any of his other contemporary cartoon ducks. It’s this rich, endlessly entertaining persona that brings us back to spend time with him again and again—a familiar, relatable friend, a duck for the ages.

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

Donald’s voice on film was his greatest liability – audiences could only make out so much of what he said, which meant that dialogue had to be kept to a minimum. With the exception of Yakky Doodle and the odd MGM duck (who also had some of the same problems – sorry Jimmy Weldon) I’m not sure why other producers would wish to traverse that path.

And unlike MIckey Mouse, whose cartoons generally included his girlfriend and a pet dog which could be more easily duplicated, many of Donald’s cartoons were with one off characters, with only occasional appearances by Daisy & Huey, Dewey & Louie.

So, with the exception of a temper, there was very little to create a carbon copy.

Donald’s major personality in many of his theatrical cartoons was his ability to stir up trouble by doing something wrong (e.g. robbing a piggy bank, antagonizing critters) , then suffer the resulting consequences, which gave writers/directors a great deal of flexibility, as the trouble could result from either lifeforms or inanimate objects.

Certainly the handling of the Duck in the Gold Key/Whitman comic book world greatly expanded, most notably through Carl Barks – helped greatly by the reader being able to understand everything Donald Duck said.

But also Donald Duck often appeared as a supporting character in stories such as the Uncle Scrooge world expeditions, where his major role was simply to react to the various situations rather than progress the plot.

Mickey Mouse’s character also expanded during this same Gold Key/Whitman period.

Whereas in the 1930’s he was happy-go-lucky, probably aged in his early 20’s, by the comics he acted more like a 35 year old.

There was the Paul Murry serials battling Black Pete and the bearded henchman emphasising adventure, while Mickey’s own comic book featured detective and mystery stories with recurring characters including The Phantom Blot, Police Chief O’Hara, Sherlock Hemlock and others.

And the Jack Bradbury illustrated Mickey Mouse comics had a greater emphasis on humour, periodically expanding on his relationship between Morty And Ferdie.

And unlike many of the cartoons of the 1940’s and 1950’s, MIckey was rarely the secondary character in those comic book years.

But in the greater scheme of things, if Donald appears more complicated, then it is more likely because the character too often exudes the sometime reckless characteristics of ourselves. Donald Duck getting increasingly aggravated because he can’t open a window – only to be shown by Daisy that he forgot to unlock it first.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts!

That’s an insightful conclusion to this fascinating series of columns on Donald Duck, and a very fine piece of writing withal.

Donald may also have been an inspiration for the mother duck in Fleischer’s “The Foxy Hunter” (1937), given her violent temper and stream of incomprehensible imprecations. Jack Mercer couldn’t replicate Clarence Nash’s duck voice, but he gives a terrific performance in that cartoon; and it’s nice, for a change, to see the cantankerous duck come out on top — while Junior and Pudgy get what’s coming to them, in the end!

Thank you, Paul! I appreciate your comments, and thanks too for pointing out “The Foxy Hunter”!

You know it’s funny you bring up the Daffy rivalry because I think for non-cartoon fans, the two kind of blur together due to Jones’ Daffy becoming the defining characterization and having a similar short-tempered greedy persona.

Hmm. Interesting observation, and certainly on the minds of the Roger Rabbit negotiators. But Daffy was never, ever lovable. Donald is never not.

Thanks to both of you for your observations — more food for thought! I’ve never had a good excuse to do any extensive research on Daffy Duck, but I’ve always found him a really interesting character.

Great insights into Donald Duck as always. Looking forward to the book. I might argue that part of Donald’s success was not because of his distinctive voice but in spite of it.

On the Donald’s Silver Anniversary episode (November 1960) of the weekly Disney television show, Walt Disney stated: “But of all Donald’s accomplishments, we’re the most proud of his efforts in spreading good will throughout the world. You might say Donald speaks a universal language. That is to say, that no one can understand what he says in any language, but the whole world laughs at him.”

In an interview, Jack Hannah told me, “We had to pantomime pretty well in the drawing what the Duck was thinking or doing because if you tried to get over a gag or a line of dialog with understanding, you were in trouble using that voice.”

So part of Donald’s success was that he was actually a pantomime character like the Pink Panther so it would take more effort and drawing to get the character across something that other studios trying to imitate him probably weren’t willing to do. I think I could also argue that part of his success was that he had pretty much the same screen persona as Bob Hope did in his films for the 1930s -1950s, the vain, frantic coward who was his own worse enemy but was somehow still lovable.

Thank you for sharing this, Jim. I’ve always liked Donald’s voice, but you’re right, it’s undeniable that he’s primarily a pantomime character. And for me, that’s a plus; all the riches of Disney soundtracks notwithstanding, I still think of animation as primarily a visual medium. I have to admit, it’s never occurred to me to compare Donald Duck with Bob Hope!

I think the Hope/Duck analogy is a bit of a stretch, but one thing they definitely have in common is a voice that’s next to impossible to imitate. About the only person who has ever done a competent impersonation of Bob Hope is Dave Thomas of SCTV. Even Rich Little, who toured with old Ski Nose in countless USO shows, never attempted it. Rob Paulsen, Jess Harnell and Tress MacNeille of “Animaniacs” used to warm up for their recording sessions by doing their take on Bob Hope; it was far from accurate but still pretty funny, with all three of them going at once.

Donald Duck is such a fascinating character. I’ve met Donald Duck comic artist Don Rosa a few times, and it’s interesting how he is considered a big deal over in various countries (especially in Europe) because Donald Duck is absolutely huge in those places. Contrast that with the United States, where most people don’t even know if Disney comics are still being published.

Great article, JB, looking forward to the book!

Thank you, Scott! Full disclosure: I’m coming primarily from the film side, so comics are sort of a second language for me. David is far more knowledgeable about the comics than I am, so I’ve been getting a crash course from him and from others, especially during work on this project.

Favorite Donald Duck cartoon, out of so many worthy candidates: I would pick Dick Lundy’s “Donald’s Tire Trouble” (1943), a magnificent solo performance – it’s just duck against machine. As for Carl Barks, I’m a worshipper since childhood, and was intrigued and delighted to eventually discover that Barks had in fact been a vital part of the animation Duck team almost from the start, before making the permanent switch to comic books in 1942, and that he had made vital contributions to the gags, story and layouts of so many favorite shorts: Good Scouts, Cousin Gus, Timber, etc, etc.

Can’t wait for the book!

Thank you for sharing these thoughts! I agree, some of Donald’s cartoons seem designed as exercises in nuanced character animation, and “Donald’s Tire Trouble” is a great example. And yes, I do think it’s significant that Carl Barks had a thorough grounding in Donald’s animated cartoons *before* he (Barks) went on to his great accomplishments in the comics.

Great article J.B, as usual. To me Donald Duck in The Three Caballeros, smitten with love and turning completely crazy over bathing beauties is hilarious and so politically incorrect these days!

Re: Donald’s voice

I always admired “Donald’s Diary” [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3TGw3j2M0I] because they gave him an attractive interior voice; no matter what *we* thought he sounded like, he spoke to himself with the voice of Ronald Coleman, which I think is only just.

I completely disagree that Donald ever “panics at the first sign of real trouble”

He’s always been far braver than even Mickey, certainly in the cartoons.

As for the comics, people forget that Donald in the Floyd Gottfredson comics and early Al Taliaferro comics were much younger and even in their early cartoons, was much younger and smaller than even Mickey. He has to stand on a wastebasket just to look over the desk!

In the much exaggerated “House of Seven Haunts,” (which is a far cry from the more accurate portrayal of Donald in Lonesome Ghosts who is the only one of Mickey’s friends to punch a real ghost), Donald isn’t afraid of any mere danger. He’s specifically afraid of Ghosts as is, it should be remembered, just about everyone else in that story including Minnie and Clarabelle. But people conveniently forget that Donald was the only to don actual weaponry (two pistols and catcher’s gear).

In the “Dognapper,” Donald is again younger and smaller than Mickey and can’t even reach to look through the window. He’s less experienced but still shows courage when he copies what Mickey says to Pete.

This is a duck who early on in his career was bada$$ enough to headbutt a grown mountain goat and Mickey was asking HIS help to defeat an eagle (“Alpine Climbers,” 1936), punched a shark in “Seas Scouts,” 1945 and Uprooted utility poles and trees (“Cured Duck, 1945).

Carl Barks then of course added even more adventure and heroism to the Duck and saw Donald defeat three guys consecutively, a truckload of smugglers by himself, hook a sturgeon as big as a whale, fight lions, and so on.

People need to stop shortchanging Donald. He’s tougher than Mickey who in both cartoons and comics is protected by Plot Armor. Mickey is a hero, sure. But it’s easy to be a hero when things come easily and things mostly go your way. It’s much harder for Donald and yet most times he choose to fight and do the right thing anyway.

I hope no one forgets that.