Donald Duck in Close-Up #4

A scene from “Out On A Limb” (1950)

At the end of World War II, businesses and individuals across America and around the world faced a profound shifting of gears. The Walt Disney studio was no exception. Throughout the war years Walt and his artists had been planning ahead for postwar production, and now they prepared to put those plans into action in a world that had changed radically since 1941. Walt himself, characteristically, was anxious to move on, to embark on new projects and explore new ideas. While he busied himself with package features, live-action production, educational pictures, and other new interests, the studio’s established activities—such as production of theatrical cartoon shorts, the company’s bread and butter since its earliest days—occupied relatively little of his attention.

Not that Walt ever turned his back entirely on the production of new Disney shorts. But by now the shorts units had been operating for some time, had established a proven track record, and could function with a measure of autonomy. The Donald Duck unit, in particular, had already been entrenched as a reliable Disney mainstay even in the prewar years, and Donald had continued to appear regularly on theater screens throughout the war. Now, with the coming of peace, the releases rolled on uninterrupted, and reflected the new reality in which the artists—and humanity at large—found themselves.

Not that Walt ever turned his back entirely on the production of new Disney shorts. But by now the shorts units had been operating for some time, had established a proven track record, and could function with a measure of autonomy. The Donald Duck unit, in particular, had already been entrenched as a reliable Disney mainstay even in the prewar years, and Donald had continued to appear regularly on theater screens throughout the war. Now, with the coming of peace, the releases rolled on uninterrupted, and reflected the new reality in which the artists—and humanity at large—found themselves.

Generally speaking, that new reality took two forms. On one hand, America and the world rejoiced at the prospect of peace, and many in society quickly retreated to the comfort of harmless, “safe” entertainment. Some of Donald’s pictures followed that path of safety, offering mild cartoon battles that were long on mischief, short on wilful mayhem. This development coincided with the arrival of a new director at the head of the Donald Duck unit.

Almost from the beginning of Donald’s starring cartoons, Jack King had been the leading director of the unit, directing nearly fifty Duck pictures in the space of nine years. But King left the Disney studio in 1946, and his place as the top Duck director was taken by Jack Hannah, a former animator and writer in the unit. Hannah promptly went to work developing new foils for the irascible duck, perhaps most notably the chipmunks Chip and Dale.

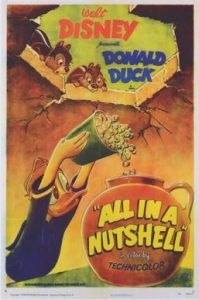

Disney fans know that a pair of mischievous chipmunks, loosely based on the little rodents in Snow White, had started turning up in Disney cartoons during the 1940s and finally crystallized as Chip and Dale. My colleague David Gerstein, conducting research for a major forthcoming book, has discovered that the road to these characters’ creation was more convoluted than hitherto suspected. Among other things, as early as 1941 they were proposed as antagonists for Donald in a cartoon that was never completed. They came into their own as Chip and Dale in 1947, under Hannah’s direction, and he soon settled into a formula pitting Donald in harmless skirmishes against some stock opponent—often the chipmunks or some similarly tiny substitute: a beetle in Bootle Beetle, ants in Tea for Two Hundred, or a bee in a series of several shorts.

Disney fans know that a pair of mischievous chipmunks, loosely based on the little rodents in Snow White, had started turning up in Disney cartoons during the 1940s and finally crystallized as Chip and Dale. My colleague David Gerstein, conducting research for a major forthcoming book, has discovered that the road to these characters’ creation was more convoluted than hitherto suspected. Among other things, as early as 1941 they were proposed as antagonists for Donald in a cartoon that was never completed. They came into their own as Chip and Dale in 1947, under Hannah’s direction, and he soon settled into a formula pitting Donald in harmless skirmishes against some stock opponent—often the chipmunks or some similarly tiny substitute: a beetle in Bootle Beetle, ants in Tea for Two Hundred, or a bee in a series of several shorts.

But if some of Donald’s postwar cartoons fell into a juvenile pattern, others veered toward more adult content. The experience of WWII had left many in society with a malaise that lingered into the peacetime years, manifesting as a new toughness and wary cynicism. The movie genre that we now know as film noir flourished during these years, painting a dark, downbeat cinematic picture of American life. Donald’s cartoons rarely ventured that far, but occasionally did reflect a new maturity (if that’s the word), probing his psychology and the perverse misfortunes of his world. Donald’s bad temper had always been his undoing, and in Cured Duck (1945) he made an honest effort to confront his inner demons and change his behavior. In Donald’s Dilemma (1947) a blow on the head replaced his famous squawking voice with the smooth, crooning tones of a pop singer, simultaneously causing him to lose his memory and shun his loyal Daisy. Conversely, in Donald’s Dream Voice (1948) he discovered some pills that changed his squawk to an elegant, cultured voice reminiscent of Ronald Colman—but only temporarily. The key to a successful new life remained, tantalizingly, just out of his reach. It’s worth noting that all these cartoons were directed by Jack King, some of them still unreleased at the time King himself departed the studio.

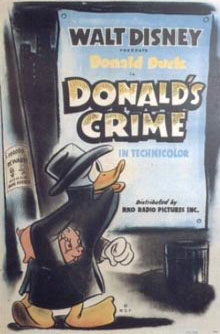

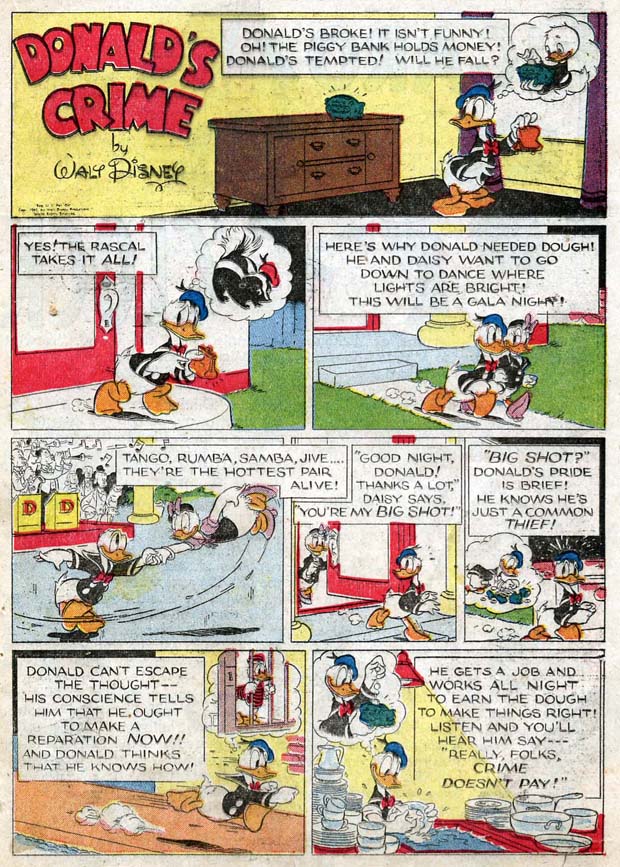

Donald’s Crime (1945) is a particular favorite of mine from these years. It’s often overlooked today, but I think it’s a classic. The first part of the film, depicting Donald’s struggle with his conscience over the temptation to rob his nephews’ piggy bank, is memorable enough, and his subsequent date with Daisy is likewise first-rate cartoon storytelling. But then the film takes a sharp turn, plunging Donald into a satiric film-noir nightmare as his conscience takes over again. Suddenly we’re in very unfamiliar territory, as Donald’s worst fears take visible form in a dark, surreal cityscape.

Donald’s Crime (1945) is a particular favorite of mine from these years. It’s often overlooked today, but I think it’s a classic. The first part of the film, depicting Donald’s struggle with his conscience over the temptation to rob his nephews’ piggy bank, is memorable enough, and his subsequent date with Daisy is likewise first-rate cartoon storytelling. But then the film takes a sharp turn, plunging Donald into a satiric film-noir nightmare as his conscience takes over again. Suddenly we’re in very unfamiliar territory, as Donald’s worst fears take visible form in a dark, surreal cityscape.

This little gem is worth examining in greater detail. The basic story situation, a character tormented by his conscience, had been percolating in the Disney story department since 1936, when writer Dick Creedon suggested it as a story for Pluto. Repurposed for Donald Duck, it started production in December 1943 with direction assigned to Jack Kinney. It was later reassigned to Jack King, and it is King’s name that appears in the credits, but Kinney’s influence is unmistakable (the head of the story crew, Ralph Wright, was one of Kinney’s frequent collaborators). A glance at the credits reveals that the animation is in the hands of seasoned “Duck men.” Paul Allen’s scenes of Donald and Daisy, dancing at the nightclub, bear more than a passing resemblance to the scenes he had animated for the classic Mr. Duck Steps Out five years earlier. Effects animation wizard Josh Meador contributes his expertise at several intervals; and Ed Aardal, primarily an effects artist himself, blurs the distinction between effects and character animation in some of Donald’s fast-action scenes.

2311

Released 29 June 1945 by RKO Radio

Released 29 June 1945 by RKO RadioMPPDA certificate 9975

Director: Jack King

Music: Ed Plumb

Story: Ralph Wright

Layout: Ernest Nordli

Backgrounds: Merle Cox

Animation: Don Towsley (Donald anticipates date with Daisy, discovers empty purse and tempted to rob piggy bank, wrestles with conscience; nephews enter, dialogue with Duck, Duck orders them to bed; nephews race upstairs to bed; Duck with Wanted poster and pursued by bloodhounds and police; Duck trapped in alley; Duck in convict stripes and discovers cafe, finds Help Wanted sign and races inside)

• Bill Justice (Duck’s efforts to open piggy bank; Duck surrounded by scattered coins and called upstairs; Duck kisses nephews goodnight, transforms into skunk and exits)

• Tom Massey (piggy bank breaks on Duck’s head, scatters coins; Duck’s relieved CU in nephews’ doorway; cat in ashcan; Duck hides behind wall and runs up stairs; Duck washes dishes and drops coins in piggy bank)

• Paul Allen (groggy Duck CU after being hit by piggy bank; Duck and Daisy dance; Duck walks Daisy home, goodnight kiss, Duck swoons and floats away; Duck tries to retrieve extra nickel, nephews catch him with piggy bank and cry, closing scenes)

• Harvey Toombs (Duck transforms into big shot, then fugitive as voice berates him;

Duck at top of stairs and on roof, leaps across chasm to other building, grabs at bricks, runs to opposite end of roof and falls off)

• Lee Morehouse (Duck in elevator shaft)

• Ed Aardal (Duck slides down drainpipe, hits lamppost, then runs around corner)

Efx animation: Josh Meador (nightclub marquee; trumpets melt; cafe sign flaps and falls)

Assistant director: Joel Greenhalgh

Today Jack Kinney’s reputation rests largely on his sports cartoons starring Goofy, but his preliminary work on Donald’s Crime was not his first or last brush with Donald Duck. Six weeks after this film, the studio released Duck Pimples, another short featuring abstract imagery and elements of film noir, and this time Kinney did receive screen credit as the director. And, as the world continued to change in the postwar years, he and other Disney artists ensured that Donald’s world would continue to change with it.

BONUS DONALD ADDENDUM

Here’s a comic page from Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories #54, March 1945, with art by Al Taliaferro. It’s a rare special promotional for a animated short, made especially for a comic book, drawn by the Duck’s regular newspaper artist, Taliaferro.

Courtesy of David Gerstein

(Special Thanks to David Gerstein and Jerry Beck)

Next Month: Donald the Educator

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

J.B. Kaufman is an author and film historian who has published and lectured extensively on Disney animation, American silent film history, and related topics. He is coauthor, with David Gerstein, of the Taschen book “Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History,” and of a forthcoming companion volume on Donald Duck. His other books include “The Fairest One of All,” “South of the Border with Disney,” “The Making of Walt Disney’s ‘Fun and Fancy Free’,” and two collaborations with Russell Merritt: “Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies” and the award-winning “Walt in Wonderland: The Silent Films of Walt Disney.”

“What say of it? What say of CONSCIENCE grim,

That spectre in my path?” — Edgar Allan Poe

You’re right, “Donald’s Crime” is an excellent cartoon, one of his best. However, I’m less troubled by the piggy-bank theft than by the fact that Donald apparently has no qualms about leaving the children alone in the house after dark.

That’s a very good point about the new direction of postwar cartoons, where characters like Donald had to deal with the likes of chipmunks and insects rather than Hitler and Hirohito. One sees this plainly in the Famous suburban Popeye cartoons of the fifties, in which the once mighty sailor man, who just a few short years earlier could turn a battleship into scrap iron with a single punch, is defeated by termites, or a mouse. Watching those cartoons in the seventies without any historical context, I could not fathom why the character had been taken in such a weird and inappropriate direction. But in postwar America, when battle-hardened war veterans were tearing their hair out over things like crabgrass, I suppose people wanted to laugh at those little vexations in life that just wouldn’t go away.

Jack King seems to have retired from animation after leaving Disney, even though he was only around 50. Was he in poor health?

Donald’s Crime and Duck Pimples stand out among other Disney cartoons of the time because they deal in fugue states (as does Kinney’s earlier Donald cartoon, Der Fuhrer’s Face), allowing the Disney animators to indulge in surreal imagery and dreamlike logic. Stuff like this was very common in cartoons in the 1930s, but by the mid forties it was rarely seen outside of Tex Avery’s MGM shorts and some of the wilder Looney Tunes. UPA’s design experiments would provide a similar sense of surrealism, but in a more formalized manner.

“Donald’s Crime” was nominated for an Oscar, but it lost to Tom and Jerry.

Is the “major forthcoming book” comparable to the huge Mickey book but dedicated to Donald?

It seems that a lot of cartoon characters from Disney, Warner, Lantz, and Famous/Paramount embraced the suburbs as their default backdrop after the war, largely displacing city apartments, rural homes and friendly slums. At best they might blur slightly with old fashioned small towns. For that matter, so did television sitcoms. It was almost a campaign to declare this was how middle-class America SHOULD live, and generally did.

Curious to know who voiced Donald’s conscience in this cartoon. Sounds a lot like Frankie “Lampwick” Darro.

Thanks for mentioning “Duck Pimples.” It’s the closest Disney every got to the Avery Universe (and “Who Killed Who?” in particular) and deserves a much bigger reputation than it has. And of course Pauline would appear to be the inspiration for a certain Ms. Rabbit over four decades later.

“Donald’s Crime” is one of my favourites, and I’m thrilled to see an animator breakdown for it at last. I’m not sure what you mean about Jack Hannah taking over from Jack King, though… he had been made a director a few years before King left the studio, and shorts by both directors appeared concurrently throughout the mid-40s.

True. Donald’s Off Day was the first Donald short directed by Hannah and it was released 1944.