The last animated feature released during Walt’s lifetime resulted in two unusual LP albums, one very elaborate and the other running only 14 minutes!

WALT DISNEY’S SWORD IN THE STONE

Narrated by Karl Swenson and Junius Matthews

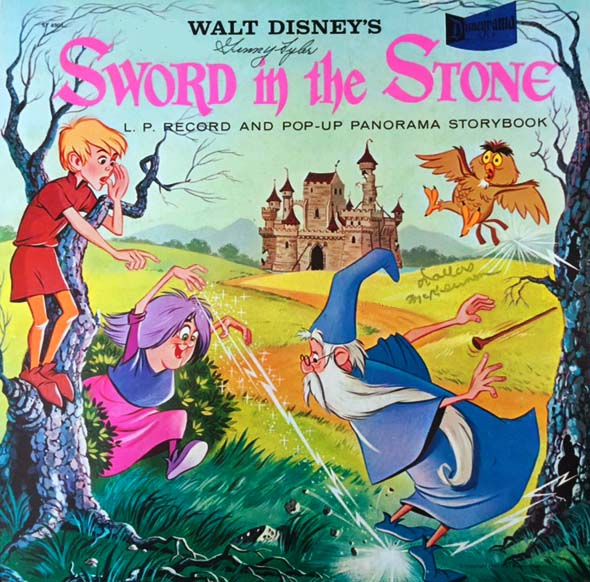

Disneyland Records – Disneyrama Series ST-4001 (12” 33 1/3 RPM LP with Pop-Up Book / Mono)

Released in 1963. Executive Producer: Jimmy Johnson. Producer: Tutti Camarata. Musical Direction: George Bruns. Running Time: 41 minutes.

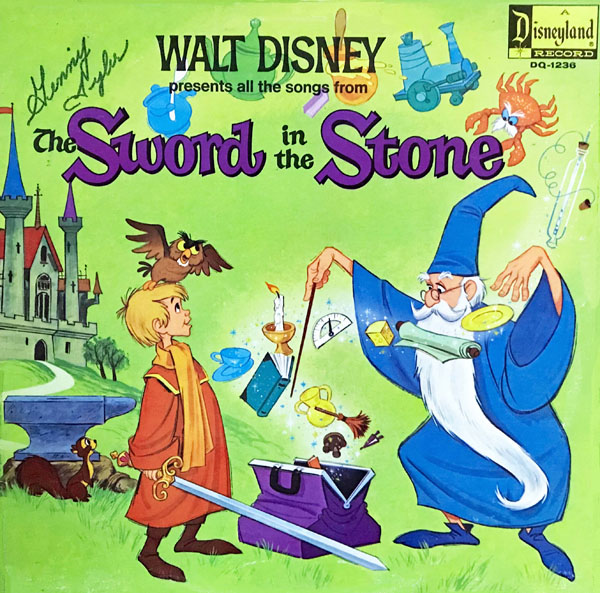

WALT DISNEY PRESENTS

ALL THE SONGS FROM THE SWORD IN THE STONE

Narrated by Karl Swenson and Junius Matthews

Disneyland Records DQ-1236 (12” 33 1/3 RPM LP / Mono)

Released July 12. 1963; reissued in 1972. Executive Producer: Jimmy Johnson. Producer: Tutti Camarata. Musical Direction: George Bruns. Running Time: 14 minutes.

Voices: Karl Swenson (Merlin); Rickie Sorenson (Wart); Junius Matthews (Archimedes—story album only); Fred Darian (Minstrel); Ginny Tyler (Squirrel); Dal McKennon (Sir Ector–story album only); Sebastian Cabot (soundtrack clip in “The Legend of the Sword in the Stone”).

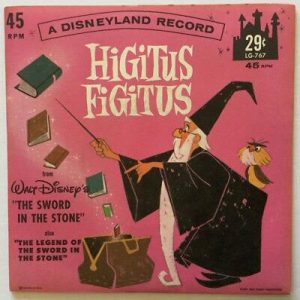

Songs: “The Legend of the Sword in the Stone,” “Higitus Figitus,” “That’s What Makes the World Go ‘Round,” “A Most Befuddling Thing,” “Blue Oak Tree” by Richard M. Sherman, Robert B. Sherman.

The Sword in the Stone tends to get lost in the shuffle of the higher-profile Walt Disney animated features. At the time, some felt that it took a little too jaunty approach toward T.H. White’s novel, though there are wry, humorous touches in the book, like Sir Pellinore’s proud sharing of his collection of the “nice fewmets” from the questing beast.

The Sword in the Stone tends to get lost in the shuffle of the higher-profile Walt Disney animated features. At the time, some felt that it took a little too jaunty approach toward T.H. White’s novel, though there are wry, humorous touches in the book, like Sir Pellinore’s proud sharing of his collection of the “nice fewmets” from the questing beast.

The 1963 film is simple, direct and completely free of pretention. The characterizations are strong and the animation is done by many of the “great masters.” For those who never quite got used to the “scritchy lines” of the Xerox process, perhaps it doesn’t fit the medieval setting as well as the modern London one in Dalmatians, but then, Mary Poppins’ animation was also done in “scritchy” and (most of) the world was thrilled.

At least a decade or so of recent animated features owes a lot to The Sword in the Stone. The unsteady but determined underdog, training for a seemingly impossible but inevitable triumph has long passed the al dente stage in animated storytelling (to use a pasta cooking term). Few if any can claim the bright-eyed, crystal-skied tone of The Sword in the Stone.

Family audiences in the early sixties may have a lighter touch. Even then, letters poured into The Walt Disney Studios from parents who were concerned about frightening sequences in some of the Disney films (this is nothing new). Peter Pan and Lady and the Tramp, while they had moments of danger, were largely upbeat and very successful in their first runs. The studio was experiencing a bonanza with more recent live-action comedies.

Family audiences in the early sixties may have a lighter touch. Even then, letters poured into The Walt Disney Studios from parents who were concerned about frightening sequences in some of the Disney films (this is nothing new). Peter Pan and Lady and the Tramp, while they had moments of danger, were largely upbeat and very successful in their first runs. The studio was experiencing a bonanza with more recent live-action comedies.

This must have influenced the decision to take a more cheery approach. As the real life sixties became progressively more grim, it proved prudent.

The messages in The Sword in the Stone are self-confidence, education and accomplishment through effort. Wart gets to be king by a legendary means, but once he gets it, it doesn’t solve his problems. It only begins new challenges. The prize isn’t as important as the road to what he learned and what is ahead to discover.

The Sword in the Stone did respectably in ticket sales but did not produce the box office return of 101 Dalmatians—but then, how could this possible top a screen filled with cute puppies and Marc Davis and Betty Lou Gerson’s immortal Cruella? It wasn’t a merchandise cornucopia, either, which is an honest factor in any mainstream animated feature. Many remember the items fondly, such as the placemats available from Gulf gas stations, and the very impressive View-Master 3-D slide packet with stunning images created by Florence Thomas.

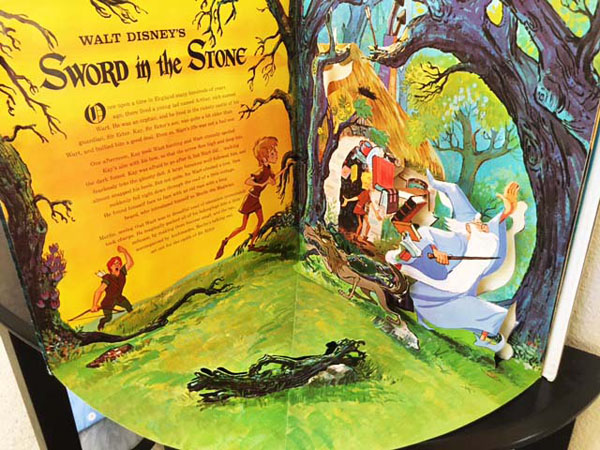

Disneyland Records made The Sword in the Stone the premiere property to kick off a spectacular new line of “Disneyrama” story LP packages. Each album contained a record with the story and songs with a four-scene, fold-out card-stock diorama with the story printed on each scene. Also in the series were Pinocchio, 101 Dalmatians, Mother Goose Nursery Rhymes and Dumbo.

As of this writing, there has never been a soundtrack album of The Sword in the Stone. However, the studio re-creations are among the finest produced by Disneyland Records, featuring original cast members Karl Swenson, Ricky Sorenson (whose voice had begun to change), Junius Matthews, Ginny Tyler and even a soundtrack snippet of Sebastian Cabot. A smaller but still full-sounding orchestra was assembled to provide some background music for the album, in addition to the songs.

Special mention goes to Disney Legend (and friend of Mouse Tracks) Ginny Tyler for the performance she created for the album. One of the first rules of great voice acting is to be an actor, rather than create a funny voice. When the voice is a vocal effect or an animal interpretation, it takes remarkable skill. The love-struck, chitter-chattering squirrel in the film version of The Sword in the Stone is still mentioned as a standout character today.

Special mention goes to Disney Legend (and friend of Mouse Tracks) Ginny Tyler for the performance she created for the album. One of the first rules of great voice acting is to be an actor, rather than create a funny voice. When the voice is a vocal effect or an animal interpretation, it takes remarkable skill. The love-struck, chitter-chattering squirrel in the film version of The Sword in the Stone is still mentioned as a standout character today.

For the LP record version, Ginny was given an exclusive opportunity to showcase the little squirrel purely through voice alone. This occurs during the instrumental bridge midway between Merlin’s verses in the song, “A Most Befuddling Thing.” In those few seconds, Ginny imbues the delightful little personality with a variety of emotions, from vivacious and playful to and affectionate and vulnerable. It’s completely possible to listen to this but forget there is no picture.

The only quibble with the album is how abruptly “The Legend of the Sword in the Stone” closes the album. On the “songs-only” album version (DQ-1236), the ballad concludes at its proper end, on a magnificent high note. This should have been the way the story LP ended as well. Instead, the story version ends with the lower note from the first verse—the middle of the song. It would have been complete perfection to top the album off with the soaring chorus and that golden note. This is just a quibble, and maybe it was not possible for some production reason.

The singer of “The Ballad of the Sword in the Stone” on the record (and in the movie) is not The Hobbit’s Glenn Yarbrough, as your writer thought years ago. It is nightclub and recording vocalist Fred Darian, co-author of the hit novelty song, “Mr. Custer.” He also crooned romantic tunes as well as folk and country, sometimes under the names of Cal Rodgers and Rome Singleton. One of his records, “Magic Voodoo Moon,” is conducted by Bill Loose, a busy composer of library cue music composer used in early TV shows and early Hanna-Barbera cartoons. Our colleague Don Yowp has more about Loose here.

The singer of “The Ballad of the Sword in the Stone” on the record (and in the movie) is not The Hobbit’s Glenn Yarbrough, as your writer thought years ago. It is nightclub and recording vocalist Fred Darian, co-author of the hit novelty song, “Mr. Custer.” He also crooned romantic tunes as well as folk and country, sometimes under the names of Cal Rodgers and Rome Singleton. One of his records, “Magic Voodoo Moon,” is conducted by Bill Loose, a busy composer of library cue music composer used in early TV shows and early Hanna-Barbera cartoons. Our colleague Don Yowp has more about Loose here.

This is the first and only animated feature from Walt’s day in which every song was written by the Sherman Brothers. All six were also released on a Disneyland LP without a book. It’s one of the shortest albums in the Disneyland Records catalog, at just fourteen minutes. The 45 rpm EP with four songs is not much shorter.

When The Sword in the Stone was reissued to theaters for the first time in 1972, for some reason the story album was overlooked and only the song album was reissued. Perhaps the sales were better for the song album because the Disneyrama was more expensive, but quite often story albums were reissued as single discs.

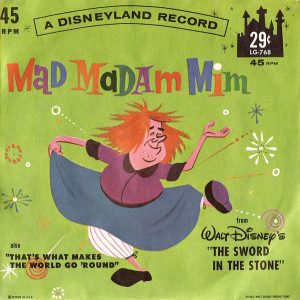

Delightful as the songs are, they rarely popped up on compilations in the ensuing years. One exception is the Wizard’s duel excerpt, including the “Mad Madam Mim” song, that was lifted in its entirety for the 1966 Disneyland album All About Dragons, narrated by Thurl Ravenscroft. The album was explored in this Animation Spin.

GIVE A LITTLE LISTEN

The Sword in the Stone

Storyteller listeners note the unusual “substitute narration,” when Archimedes picks up the story when Merlin is away. On most records, a single narrator simply explains the absentee action anyway, since it was past tense anyway. This was a nice detail.

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

GREG EHRBAR is a freelance writer/producer for television, advertising, books, theme parks and stage. Greg has worked on content for such studios as Disney, Warner and Universal, with some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. His numerous books include Mouse Tracks: The Story of Walt Disney Records (with Tim Hollis). Visit

There’s a very simple reason that the storybook album is so long and the song album is so short: because, as Disney features go, “The Sword in the Stone” has remarkably little music in it. It’s a very talky movie, probably the most dialogue-heavy in the Disney canon, and the first rule of film scoring is never to let the music get in the way of the dialogue. Whole minutes go by without a single note of music. Most of the cues are very brief, only a few bars long, just to set the mood for an establishing shot or a magical spell or to mickey-mouse an onscreen gesture. In only a few places (Wart’s animal transformations, Merlin’s magical duel with Madam Mim) does the music really contribute emotionally to the story, and when it does, it’s as effective as any score George Bruns ever composed. But he must have had to restrain himself due to the sheer wordiness of the script. Even during the action sequences, the characters never stop talking. I think it’s no coincidence that the film’s most powerful emotional moment is provided by a character who doesn’t say a word: Ginny Tyler’s girl squirrel.

These are perhaps the most inane songs the Sherman brothers ever wrote for a film. All that hockety-pockety higgitus-figgitus zim-zam-zoom is just — well, discomboomerating. But I’m grateful that Walt gave them a second chance.

Disney’s Sword in the Stone film is like a signpost. It points the way to the later legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, as told by Malory and numerous others. It also points the way to the original book by T. H. White. I first read the book “The Sword in the Stone” as part of the larger novel “The Once and Future King”, a book which changed my life.

Not much evidence of Arthur’s future greatness is offered in the Disney film. We sort of have to take Merlin’s word that Arthur will become a great king later on. This is why pairing this film with the musical film “Camelot” helps to bring about a richer understanding of the significance of the Wart’s education as administered by Merlin. Both are based on the writings of T. H. White. But there is no substitute for T. H. White’s novel, just as the novel is no substitute for Le Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory. Each sort of leads the way to the other. With the Disney film as a good foundation and lead-in. I don’t know about anyone else, but when I saw the film as a child I immediately wanted to know more about King Arthur and Merlin. Thus began a life-long quest which continues to this day.

I agree with your statements about the storyteller album, which unfortunately never saw a reissue. Unfortunate because it is one of the best-produced albums in the Disneyland Records catalog. For a re-creation it pulls out all the stops. Wonderful voice work by most of the original artists, great musical re-interpretations of the score. And yes, the ending is weak and somewhat tacky by comparison with what has come before. I completely concur with your assessment. The song’s finale should have been used as the note on which to end. Would have given it a richer finish.

One thing you didn’t mention is that in the 70’s there was one more issue of the songs-only album as part of the Disneyland Records “Double Feature” series, in which two albums would be paired under one double set of covers, usually with a common theme. Thus the music of “The Sword in the Stone” was reissued with a re-release of the storyteller album “The Prince and the Pauper.” (Maybe someday one of these spins could cover those “Double Feature” albums?) In this way, while the storyteller of “S in the S” was not reissued, there was another story about a king and a crown that was a good story in its own right (despite the two leading characters being portrayed vocally by women and not by boys).

I would also love to know more about the “Disney-Rama” series and why it was so short-lived. What was the marketing strategy behind it? Was it a popular format at first? Was it too expensive to justify further installments? And why was the “Sword in the Stone” the only item from the series never to see the light of day after its initial release?

Thanks for the information about Fred Darian. Like you, I always assumed it was Glenn Yarbrough. Great post! Any inside information about the golden age of Disneyland Records is greatly appreciated.

Frederick – thank you for mentioning the Disneyland Double Feature reissue in 1972, yet another issue of the shorter “songs only” album. Maybe that was a reason why the song album was reissued instead of the story LP because all the Disneyland Double Feature sets were shorter albums that were a better value when sold together.

At this point, it is anyone’s guess because there isn’t data available. Almost every actor in the story version was also in the songs-only version. Perhaps there was a contractual issue with Bill Peet since he was given a major story credit and may even have written the album.

The Disneyrama series came and went but a lot of albums must have been manufactured because they still “pop up” for sale every so often. The obvious answer must have been that, when parents especially were shopping for records, the Disneyramas must not have seemed worth the higher price when a perfectly good one cost far less.

There is one other issue with the Disneyrama albums as well–unless there was additional advertising on the original shrinkwrap, the covers do not explain the contents. This might be the most logical reason.

This mistake has been sadly repeated, and it can be devastating in retail sales. All you have to do is watch people looking at the items. An album is released in a beautiful, gorgeous package but it says little or nothing about the beautiful, gorgeous AUDIO RECORDING being purchased. The Sword in the Stone Disneyrama LP cover said nothing about the songs, composers, cast, story, but it sure looked nice. With little or no information about why the record buyer should pay extra for it, the less expensive item that offers information will logically sell better. The wise thing to do is to add a large removable sticker or card to the package, as was done on the Fantasia set (but then, it was also Fantasia).

The evidence of this mistake apparent on Disneyland Storyteller albums as they progressed through the ’60s. The back covers emphasized “all these pages inside,” showed what looked like a lot of pages, while the copy drove the contents home in one sentence and made it sound grand: “A magnificent full-color illustrated book and long-playing record.”

Jimmy and Tutti were successful because they recognized and learned from setbacks and mistakes. Come to think of it, so did Walt.

Not Glenn Yarbrough? I would never have guessed it!

I still wonder about the Shermans’ original intended purpose for “Blue Oak Tree.” In the LP, a sumptuous production of it is used to open the tournament in London, but in the movie, only a couple of lines are heard elsewhere in the story as part of a drunken revelry. Did it even have a spot in the film where the full version was supposed to be heard?

You didn’t refer to the competing coverage on Little Golden Records. Jim Timmens (with a minimalist combo of mostly rhythm and xylophone) backed some low budget covers pf at least three of the songs from the picture, On two of them (“Higitus Figitus” and “That’s What Makes the World Go Round”, vocal was provided by a competent Merlin sound-alike named Jimmy Kenny. I have never encountered the third record (only available as side two of an EP as far as U can tell), a version of the opening ballad, “The Legend of the Sword in the Stone”, so I do not know who drew vocal duties there. The other two songs comprised side 1 of the EP, bit were also available as singles. To fill our side two on the singles version, Golden wrote some original spoken material for Merlin to perform (On “Higitus”, it was “What Did Merlin Ever Do?” (a question that outrages the old sorcerer, who takes the opportunity to recount his past history of magical feats), and on the other (which I have also not heard), “How To Be a King”, which I presume includes doses of Merlin’s sage advice. Writing credit for these pieces seems to go to one Abbot Lutz (at least on “What Did Merlin Ever Do?”) The piece is clever, with some inclusion of Merlin’s fluster and bluster to keep him in character, and tells of such exploits as turning one person into someone else, and switching the someone else with another, and so on – until no one could tell the difference or who was who. A fight with a three headed dragon has the dragon bewitched so that one head slays another, a second slays the slayer, and the third head – – slays itself. The oddest thing about Golden’s coverage, however, is the apparent (at least to my present knowledge) lack of a cover of “Mad Madam Mim”. Perhaps that voice was too hard to find someone to cover for.

UPA inspired art. I’m really sicka this!

Well, we talk about of it a lot here so………..

Old enough to remember this in first release. I had the board game, which included an unnecessary little sword (you won by landing on a picture of the sword in the stone) as well as a comic book adaptation and a punch out book, the latter including a castle with Merlin’s shaky tower. Also recall a holiday parade on TV — not Macy’s, but a big one — that included a float of an outsized Merlin and a performer wearing a big head as Wart. It was a big deal, as any new Disney feature was back then, but somehow didn’t stick in the imagination the way “101 Dalmatians” and “Jungle Book” did. Perhaps it just played as too small scale, with very few characters and a quiet ending. I remember being disappointed Sir Kay didn’t turn out to be a real villain.

Fast forward to the early 80s. On a family trip to Walt Disney World, I discovered that the Contemporary Resort had a little cinema — really just a screening room with padded folding chairs — attached to a big arcade. It showed “Sword in the Stone”, “Alice in Wonderland”, and maybe another “lesser” feature in rotation. I saw “Sword in the Stone”, preceded by “Knight for a Day”, in what seemed to be slightly worn 16mm. This was just before the video revolution, when it was hard to see any Disney animated feature outside of regular theatrical release.

A detail I never considered until recently: The anvil between the sword and the stone. It does imply metal welded to metal, a tougher proposition that metal against rock, but I don’t remember seeing it in any other presentation of Arthur’s story.

There was a “talking” version of the Viewmaster set that came out as well. I had it as a kid. Aside from the scratchy, warbly audio, I loved it.

Screw the songs, gimme the SCORE!

What amazes me is how this film never got adapted into a read-along book-and-audio set (i.e. a “See, Hear and Read” title). I came up with a fictional cover for one…

https://www.deviantart.com/wilee2005/art/Retro-Disney-Sword-in-the-Stone-read-along-cover-648244708

I still maintain that part of the reason for SWORD’s lackluster box office was the mood of the country back then … barely a month after Kennedy’s assassination and the end of America’s dream of Camelot. That wouldn’t have affected the international markets as much, of course, but still I wonder ….