Suspended Animation #320

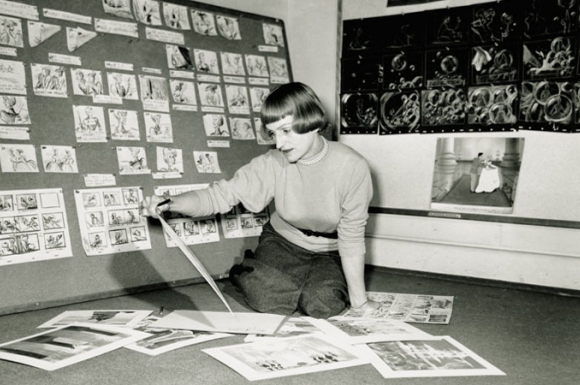

What is there left to say about Mary Blair after the outstanding and insightful books by John Canemaker? However, there are always some nooks and crannies yet to be explored.

Mary Blair had a troubled life and, in particular, had to deal with an alcoholic husband named Lee who, although a talented artist himself, seemed deeply resentful of the attention and opportunities given to his wife.

Supposedly, he never went to accept her posthumous Disney Legends award in 1991 offering some remark like: “Why did they give it to her? She’s dead. I’m still alive. They should give one to me.”

Supposedly, he never went to accept her posthumous Disney Legends award in 1991 offering some remark like: “Why did they give it to her? She’s dead. I’m still alive. They should give one to me.”

I can sense that same undercurrent of resentment in this article They Animated Fantasia by Dale Pollock, from the June 20, 1976 edition of the The Santa Cruz Sentinel.

In the full article, Lee Blair seems to dominate the conversation, focuses attention on his achievements and minimizes the work at the Disney Studio. Mary Blair comes across as very submissive and is pretty much portrayed as a housewife who has a little talent in art and helps her husband.

Once again, I am only excerpting what I feel is the most relevant information and eliminating the standard hyperbole about the magic of animation and how an impossibly large number of drawings are done for a few seconds of animation.

After meeting at art school in the depths of the Depression, the Blairs reluctantly took jobs in the earliest animation studios. “It was way beneath our standards,” confides Lee, “but we needed to eat.”

Lee and Mary worked at the MGM Studios. “Sound was in at that time,” remembers Lee, “so we had Happy Harmonies to rival Disney’s Silly Symphonies and Warner Brothers’ Merrie Melodies.”

Both Blairs continued their fine arts careers, winning prizes and competitions across the country. “It was a Jekyll-Hyde existence,” Mary recalls.

Lee picked up valuable experience that landed him a job as color director with the still-growing Disney operation. Disney had just achieved his first feature success with Snow White and Lee was rushed right into production on Pinocchio, choosing all the color layouts for the animated film.

“I remember one time we had thousands of drawings for one Pinocchio sequence that just wouldn’t work,” says Lee. ‘We tossed all of them in a big pile and since we already had the soundtrack (There Ain’t No Strings On Me), we just went through and matched up the motions to fit the music. Took us days and days.”

“I remember one time we had thousands of drawings for one Pinocchio sequence that just wouldn’t work,” says Lee. ‘We tossed all of them in a big pile and since we already had the soundtrack (There Ain’t No Strings On Me), we just went through and matched up the motions to fit the music. Took us days and days.”

With over 2,000 animators working for the Disney studio (“Walt had animators to burn,” claimed Lee), Lee was transferred to Bambi. “But that was too cutesy for me, not enough fantasy. So the great Walt called me in and said I couldn’t leave, he had a new film in mind for me.”

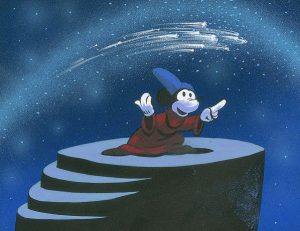

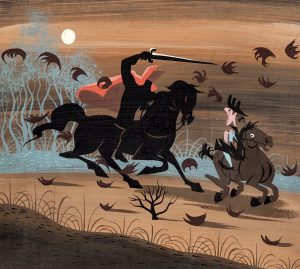

The upshot of that conversation was Fantasia which remains the Blairs’ favorite Disney effort. Lee was assigned two crucial sequences of the film: the opening abstract drawings that accompanied the tuning of the orchestra and the classic ballet of the hippos.

Every week Disney would schedule a meeting with what came to be called ‘the wrecking crew’. “If Walt was displeased,” reminisced Mary, “he’d just raise one eyebrow and you knew it was back to the drawing board”. Mary joined her husband and went to work on additional numbers that unfortunately never made it to the screen.

The advent of World War II put a halt to animated production, although the Blairs did get in one eventful trip before Lee was drafted. The State Department sponsored a Disney junket to Latin America where Lee helped conceive one of Disney’s most popular characters, the South American parrot, Jose Carioca.

The advent of World War II put a halt to animated production, although the Blairs did get in one eventful trip before Lee was drafted. The State Department sponsored a Disney junket to Latin America where Lee helped conceive one of Disney’s most popular characters, the South American parrot, Jose Carioca.

“We based him on an actual guide we had in Rio,” confessed Lee, “and he became the greatest thing down South since Mickey Mouse.”

After the war, Disney once again tried to entice the Blairs back, but Lee saw the trend going to live-action footage. Accordingly, he started his own animation company in New York, Film Graphics. With all of their past laurels to rest on, the Blairs are still in motion, much like Lee’s animated drawings.

Last year, they designed a visual presentation of Ravel’s Bewitched Child for the San Francisco Symphony, a production so successful that it toured Japan. “Animation has been good to us,” Lee says gratefully.

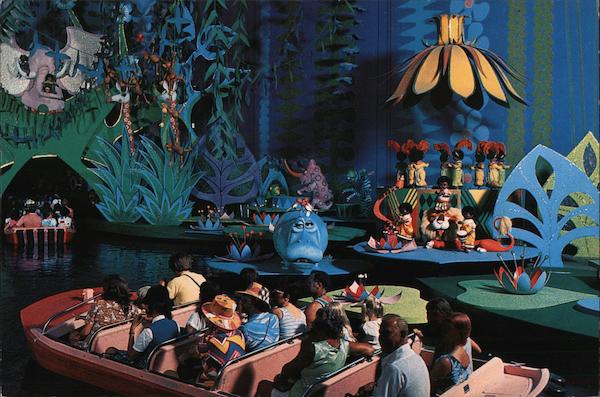

Joyce Carlson, who worked with Mary Blair on the It’s A Small World attraction for the 1964 New York World’s Fair and for Blair’s tile mural in the Contemporary resort hotel at Walt Disney World, told me in an interview in 1998:

I used to admire Mary from afar when I was in Ink and Paint and I would see her and Walt walking around the Studios. When I went to work at WED (Imagineering) in 1962 on the New York World’s Fair, I was assigned to work on the models of It’s A Small World with Mary Blair.

I used to admire Mary from afar when I was in Ink and Paint and I would see her and Walt walking around the Studios. When I went to work at WED (Imagineering) in 1962 on the New York World’s Fair, I was assigned to work on the models of It’s A Small World with Mary Blair.

Mary was very friendly and very artistic. She had a lot of glasses. She used to have a lot of different colored contact lenses as well. She used to wear green or blue or any color to go with the outfit she was wearing that day. I’d watch her put them in and I thought, “I wouldn’t want to wear those”. Maybe that affected her colors. Her colors were always bright.

She used theatrical gels and cut them up and put them on top of her artwork. I had to match the colors she picked and that was a problem because those colors didn’t exist with the paints we had. I had to go and get some of the paints from the ink and paint department and mix them in with our paint and they didn’t always mix well. It was like painting with mud.

Mary painted very flat and it wasn’t very dimensional. We often had to cut pieces of Styrofoam for her and let her move them around. She wasn’t always happy how her artwork got translated to animation but she was happy with the finished product of Small World, I think.

Mary painted very flat and it wasn’t very dimensional. We often had to cut pieces of Styrofoam for her and let her move them around. She wasn’t always happy how her artwork got translated to animation but she was happy with the finished product of Small World, I think.

Mary’s paintings are all flat. She started to learn a little dimension toward the last. But her work is charming. I only have one book of hers, the Little Golden Book children’s book that she did. That’s what we used to help us understand her design afterwards. She was a wonderful talent.

When we worked in Glendale, we didn’t have a cafeteria at WED. We had these machines for soup and coffee. So we’d go out for lunch every day and have martinis. Lee and Mary Blair would have two or three. I don’t know how I lived through that. We’d all still get our work done. It was a place called “Checks Cashed”.

Herb Ryman would come by. There was sawdust on the floor. We played pool in there. The hamburgers were forty cents and they were this big (indicates a large size) and they were great hamburgers. So we’d order a hamburger and a martini. Every day we’d go in there and have martinis but we still got our job done.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Have you read The Queens of Animation by Nathalia Holt? It goes pretty deeply into Mary Blair’s art, career, and personal life (along with those of other prominent women in animation).

Would caution regarding accuracy within areas of this particular book –

What a weird thing to say. Unsupported and without context, why should anyone take your advice? Because MJ said so? lol

With all due respect to Joyce Carlson, I think she did Mary Blair an injustice by saying that her painting “wasn’t very dimensional”. While undoubtedly stylised, her paintings employed subtle tricks of composition and perspective to create a vivid and vibrant fantasy world. They are most certainly not “all flat” in the sense that those of the artist Charley Harper are. Mary Blair’s backgrounds for Disney are so visually arresting that they often distract me from the animated characters in the foreground.

Oskar Fischinger, the German abstract artist and animator, designed the original concept art for the Toccata and Fugue section of Fantasia but quit after Walt decided that he wanted something more representational. (Fischinger was very frustrated during his few years in Hollywood, which also included stints at Paramount and MGM. Although he was well paid, none of his work for the studios was ever used as he intended it.) If it was Lee Blair who made the alterations in accordance with Walt’s wishes, they were still based on what Fischinger had already done; the sequence has all the hallmarks of his style. The composer Paul Hindemith, a friend of Fischinger’s, interviewed for a job at the Disney studio in March 1939, where he met with Stokowski and was shown the work in progress on Fantasia. Hindemith later said that the only part of the Toccata and Fugue that was not Fischinger’s work was the silhouettes of the orchestra musicians.

Incidentally, Lee Blair’s copy of the book FANTASIA by Deems Taylor, autographed by Walt Disney and twelve of the Disney artists, was sold at auction in 2017 for $4550.

I would have loved to see the Blairs’ design for the San Francisco Symphony’s production of Ravel’s one-act opera “L’enfant et les sortileges”, which I have never seen translated as “Bewitched Child”, but that’s obviously what the writer of that article meant. (The title translates literally as “The child and the magic spells”.) It’s about a naughty boy, confined to his room as punishment, who is tormented by all the animals, toys and inanimate objects he has abused. It’s seldom staged because it requires a very large orchestra (and the orchestral score is very difficult) as well as a mixed chorus, a children’s chorus, and a large cast of vocal soloists, most of whom have to play multiple roles; and since it’s only about 50 minutes long, you need another one-act just to round out the program. Therefore it’s usually done, when it’s done at all, in a concert setting with a minimum of staging. I once played a version that used puppets, but I think the opera cries out for an animated treatment! Maybe some French animated studio will rise to the challenge someday. But I won’t hold my breath.

She was always my favorite among the Disney design folks. Her work is instantly recognizable and, for a reason I’m unable to describe, comforting to me.

Thanks so much Jim! It’s refreshing to learn about Disney and Animation History and the legendary artists who had a hand in creating some of the most iconic and recognizable work today when there are few if any mainstream companies that cover them.

In “Illusion of Life”, Thomas and Johnston say that everybody loved Mary Blair’s art, but that it ceased to be Mary Blair art when combined with the kind of character animation Walt Disney wanted. It was something animators struggled to reconcile for a long time.

One wonders if Disney ever considered giving her the kind of control he granted Eyvind Earle on “Sleeping Beauty”. Of course, Earle came along when Disney’s attention was increasingly on other projects.

Find myself thinking of the “flat” designs used in one song of “The Princess and the Frog”. It’s striking and attractive, but at the same time suggests the flash animation now common on television. Comparable to how UPA’s shorts lost their original impact because they were so widely imitated on the cheap.

I’ve always thought that Mary Blair’s designs were way better than what ended up on screen. Today’s animating tools ought to be able to actually make (or remake) some of those classic Disney projects exactly handling the color and texture of those designs!

I always thought her art style and Marc Davis’ drawings sort of contemplates each other very well especially after reading that two volume set of Marc’s WED / Imagineering work (highly recommended).

Preston Blair seems to be more famous than his brother Lee. I wonder if Lee felt inferior to his wife and brother.

Well, everything that could have been done to make him feel inferior was done. In the particular case of Lee and Mary, this very article reflects quite well the type of depreciation treatment he received in these years, in order to build up his wife.

Personally, I regret Mary’s influence on post-war Disney. Althought I enjoy greatly her art, she strikes me as a poor substitute for the challenge offered by the work of the likes of Horvath, Tengreen or Grant.

I’d disagree as I find her artwork a bit more unique than most of the other mentioned. Besides, all the other were men and not a woman mentioned.

That’s exactly the point: it’s what they were and not the kind of art they were producing all that’s matters.

That approach does not favour to Mary Blair’s art, which is great in itself.

Great insight into Mary Blair’s world. Hilarious how Carlson patiently described her as never quite “getting” dimensional art until the last.

Poor Picasso never could quite get what side of the head the eyes should be on either. It held him back, I’m sure.

Mary Blair’s colors and compositions still amaze me, and her use of flat color is so eloquent.

I’ve just finished THE QUEENS OF ANIMATION and outside of Walt Disney, I can’t think of one male in the book who gets a fair assessment. Animator Gordon Sheehan knew both Lee and Preston Blair and enjoyed working with them.

I have a little suspicion about this kind of thing: years of labor mistreatment of women by the Disney studio is washed away by an operation at the expense of its co-workers (to a large extent also mistreated). It explains the easy “Salieri approach” that we can see in this note. It’s a shame, because Mary Blair’s art should be treated seriously.

Then you didn’t read it.

There are plenty of examples, but since you can’t even think of one I’ll give it to you right off the top of my head: Howard Ashman. You’re welcome.

If Mary Blair worked for Harman-Ising at MGM, why isn’t the color of the Happy Harmonies better?

She was one of the most wonderful artists at Disney, In last years I saw some tendency for the “Kricfalusi crowd” to diminish her achievements and

accomplishments on the field, just like their dissing of certain directors. Useless tantrums that can’t tarnish her legacy.