Almost every Halloween, the Walt Disney Company seems to showcase one of its earliest black-and-white cartoons, The Skeleton Dance (1929), the very first Silly Symphony.

While not specifically stated to be Halloween, merely a supernatural frolic during the midnight hour, this five-and-a-half minute innovative short cartoon certainly encapsulates the imagery and spirit of the spooky holiday.

While working with Walt Disney on the scores for the first Mickey Mouse cartoons, Carl Stalling, who was basically the Disney Studios’ first music director, had an idea that he suggested to Walt in late 1928 for a new series of cartoons with the drawings made to fit pre-recorded music.

Walt agreed to do a second series of cartoons because it would allow him to do some experimentation, not be restricted by the formula of the Mickey cartoons and generate an additional stream of revenue.

As Stalling told reseachers Michael Barrier, Milton Gray and Bill Spicer during a June 1969 interview: “He thought I meant illustrated songs, but I didn’t have that in mind at all.

“The Skeleton Dance goes way back to my kid days. When I was eight or ten years old, I saw an ad in The American Boy magazine of a dancing skeleton, and I got my dad to give me a quarter so I could send for it. It turned out to be a pasteboard cut-out of a loose-jointed skeleton, slung over a six-foot cord under the arm pits. It would ‘dance’ when kids pulled and jerked at each end of the string.”

“Ever since I was a kid, I had wanted to see real skeletons dancing and had always enjoyed seeing skelton dancing acts in vaudeville.”

Stalling used a bit of Edvard Grieg’s March of the Dwarfs (1893) but primarily composed an original fox-trot piece so it seemed lively and a little jazzy in keeping with the times.

Iwerks went to the local library for inspiration. He found pictures drawn by the English cartoonist Rowlandson of skeletons dancing. In other books, he found photographs of skeleton dances depicted upon the walls of Etruscan tombs.

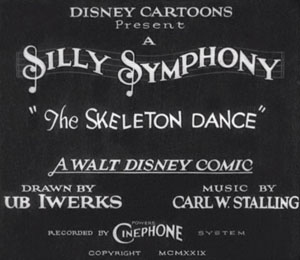

Animation under Ub Iwerks began in January 1929 with it taking almost six weeks to finish. The soundtrack was recorded at Pat Powers’ Cinephone studio in New York in February 1929 along with the fifth Mickey Mouse short cartoon The Opry House. According to Roy O. Disney’s records, the total cost for the film was $5,485.40.

Animation under Ub Iwerks began in January 1929 with it taking almost six weeks to finish. The soundtrack was recorded at Pat Powers’ Cinephone studio in New York in February 1929 along with the fifth Mickey Mouse short cartoon The Opry House. According to Roy O. Disney’s records, the total cost for the film was $5,485.40.

The Skeleton Dance was completed in March 1929 and a preview was held on March 20 that didn’t go quite as well as Walt had hoped.

As Walt’s daughter Diane Disney Miller recalled, “Father wasn’t easily discouraged. He took The Skeleton Dance to a friend who ran the United Artists Theater in Los Angeles and asked him to look at it. ‘We’re looking at some other things this morning,’ the man said, ‘and I’ll have my assistant look at it. You go with him’.

“Father sat beside the assistant while the film was run. It was just before the first morning show; a few customers had drifted in and it was obvious they liked The Skeleton Dance but the assistant didn’t listen to them. ‘Can’t recommend it,’ he said. ‘Too gruesome’.

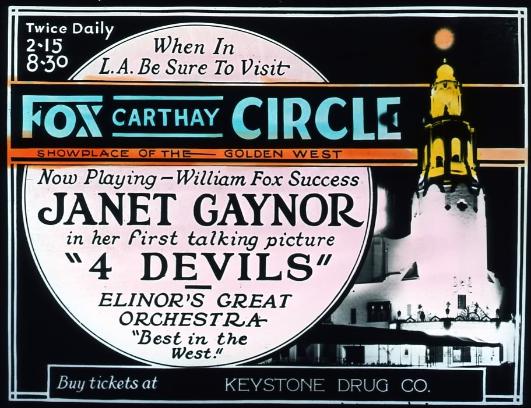

“Father got a hold of another friend and asked him if he could put him in touch with Fred Miller who managed the Carthay Circle, one of the biggest and most important theaters in town. Father’s friend sent him to a salesman on Film Row. ‘Maybe he can get him to look at your skeleton film’.

“Father found the salesman in a pool hall shooting a little Kelly (a game played on a standard pool table with sixteen pool balls where each player draws one of fifteen numbered markers called peas or pills at random from a shake bottle which assigns to them the correspondingly numbered pool ball, kept secret from their opponents, but which they must pocket in order to win the game). ‘Leave your picture here, Disney,’ the Kelly player said. ‘I’ll look at it. If I like it, I’ll get in touch with you’.

“Father found the salesman in a pool hall shooting a little Kelly (a game played on a standard pool table with sixteen pool balls where each player draws one of fifteen numbered markers called peas or pills at random from a shake bottle which assigns to them the correspondingly numbered pool ball, kept secret from their opponents, but which they must pocket in order to win the game). ‘Leave your picture here, Disney,’ the Kelly player said. ‘I’ll look at it. If I like it, I’ll get in touch with you’.

“It sounded like a stall but he actually did look at the film. When he looked he said, ‘I think Fred will like this. I’ll take it over to him myself’. As a result, Miller showed The Skeleton Dance with a feature picture he was running. It went over big.

“Father clipped the local press notices and mailed them to Powers with a note: ‘If you can get this to Roxy (the nickname of Broadway showman Samuel L. Rothafel who ran New York’s prestigious Roxy Theater), he’ll go for it the way Miller did. Powers got a print to Roxy and Roxy liked it. He ran it in his huge New York theater.”

It ran at the Carthay Circle theater along with the feature Four Devils starting on June 10th, 1929. It was the first cartoon ever programmed there and the theater would later host the Hollywood premieres of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Fantasia. Walt attended the screening with Iwerks and scratched his head. “Are they laughing at us or with us?” he asked Iwerks.

It ran at the Roxy theater on July 16th, 1929 with Pleasure Crazed. Rothafel wrote, “without exception, one of the cleverest things I have seen and as you know the audience enjoyed every moment of it.”

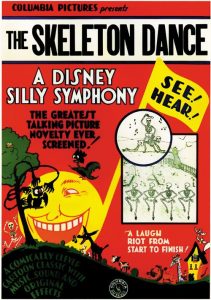

In early August, Columbia Pictures signed a contract to distribute the Silly Symphonies nationally and made the short available in late August. Its first playdate was again at the Roxy on September 7 shown with Big Time. It was the first time in history that a cartoon had had a second engagement at the theater.

Les Clark recalls that Ub animated all of The Skeleton Dance except for the first scene which Clark animated. Year later Clark claimed he had done a scene with a pair of skeletons playing the spines of other skeletons like xylophones. Wilfred Jackson supposedly animated the crowing rooster at the end of the cartoon.

In an interview done years later, Iwerks stated, “(The Skeleton Dance) was a different type of film from the Mickeys. I did all the animation but I did it rough, in line form. Other guys (Clark and Jackson) put in the rib cages and teeth and eyes and bones.”

Walt sent a print to New York for his film distributor to promote the new series. But after getting poor reactions from exhibitors who felt the film was grotesque, Pat Powers wrote back tersely: “They don’t want this. MORE MICE.” As a compromise, Walt added the title “Mickey Mouse Presents a Silly Symphony”.

Iwerks himself revisited the concept when he directed The Columbia Color Rhapsody entitled Skeleton Frolic (1937). It is very similar to The Skeleton Dance in tone and action but in full, rich color and with much more use of extreme perspective and detail.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

I always welcome any opportunity to watch “The Skeleton Dance” again. After over 90 years, it has not lost any of its capacity to awe and entertain.

That is indeed Grieg’s “March of the Dwarves” (which he composed in 1891, not 1893). The very ending, where the skeleton arm pulls the skeleton feet into the crypt, comes from Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King”, which, like the march, was in every silent film organist’s repertoire, along with J. Bodewalt Lampe’s “Villain’s Theme”, heard earlier in the cartoon. The scenario corresponds to that of “Danse Macabre” by Camille Saint-Saens, which in turn was based on a poem by Henri Cazalis; however, Stalling did not quote any of this work directly.

“Danse Macabre”, like “The Skeleton Danse”, begins with a clock chiming midnight, and ends with the crowing of a rooster (represented by the oboe) and the revellers scurrying back to their graves. “Danse Macabre” was the first orchestral work to employ the xylophone, which is featured prominently in “The Skeleton Dance”. In “Danse Macabre”, the spectre of Death is represented by a solo violin with its high E string tuned down a semitone, creating a dissonance known in early music as the diabolus in musica (the devil in music), which church composers were taught to avoid at all costs (mainly because it’s very hard to sing). This is approximated in the cartoon by the skeleton who plays a black cat’s tail like a fiddle, using a fused tibia and fibula as a bow (or possibly a fused radius and ulna; cartoon osteology is an inexact science). And like “The Skeleton Dance”, “Danse Macabre” at first had detractors who found its subject matter tasteless and gruesome, but today it’s the composer’s best-known work after “The Carnival of the Animals”.

The Danse Macabre was a popular subject of late medieval allegorical art in the aftermath of the Black Death, notably the woodcuts of Holbein the Younger. The idea being that Death is the great equaliser, and that all of us, highborn and low, will ultimately be welcome guests at the party. Happy Halloween, everybody!

Jim:

Very good research here! Interesting that Disney seemed to rely a lot on Pat Powers’ judgment on this cartoon, as he later compares Powers to a crooked street car conductor who throws his hat full of money in the air and whatever doesn’t stay up in the air he pockets! No doubt the bad feelings started when Powers lured Ub Iwerks and Carl Stalling away from Disney not long after this cartoon!

I had a late film-collecting friend who had a very nice green-toned 16mm print of this cartoon who loved to show it to friends around Halloween!

*Breaking News*

“Unskippable Disclaimers for Racism Appear on Several Old Films on Disney+”

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/disney-racism-disclaimer-dumbo-peter-pan-aristocats_n_5f8b2de2c5b6dc2d17f76d56

As much as I admire the bulk of Walt Disney’s animation output, in the past on this space I have taken issue with him on several occasions, but today I must applaud Disney for its decision to “strongly” highlight that several of their films contain “negative depictions and/or mistreatment of people or cultures.”

It is my personal belief that racially demeaning cartoons of the Silent and Golden Eras of Animation should not be swept under the rug as though they never existed. It is better to confront and discuss an uncomfortable dynamic rather than to ignore and/or forget it exists. Insensitive racial, cultural, ethnic, and religious cartoons of the past were in a small way a mirror of what the United States was, and unfortunately on several fronts what it continues to be — which is evident by the current unsettling racially divisive political and social climate that has tragically seeped into the landscape of America from “sea to shining sea.” One cannot escape the reality that the United States of America has from day one been more like the Divided States of America or simply the States of America.

From their humble beginnings, animated cartoons have always been a means of escapism—if only for 2 to 10 minutes at a time. Some cartoons are created to instruct and educate, but the sole purpose—the very essence of the vast majority of cartoons is at a minimal to put a smile on your face, and at best to give the viewer a loud, unrestrained, deep belly laugh. I’m not a fan of the cartoons from yesteryear that exploited racial caricatures, but I understand why they were made and the vital importance of making them available [uncensored and unedited] for future generations of cartoon lovers.

Neat. Thanks. Loved this from the moment I first saw it on TV as a kid.

This was a fantastic read. It’s astonishing to me that Carl Stalling is not an official Disney Legend.

Every year, I show this cartoon to a new group of ESL students at Halloween. Every year, it gets hysterical laughs and astonishment that something so old can be so entertaining. Sometimes they even get to see if they can spot the recycled bits in “Haunted House.” Quality will out, as a wise creative-type once said.

An absolute joy if a post!!! Thank YOO!!!!

Utterly fantastic details on the making of “The Skeleton Dance”! Great read!

(Jazzman, I very much appreciate your comments, too.)

And — let’s not forget the brilliant contribution of MARY TEBB — who single-handedly did all of the Inking & Painting on THE SKELETON DANCE at Disney Studios! Mary worked closely with Ub and the handful of inbetweeners who worked on this short to complete the film. She later left Disney and headed up the I&P team at Iwerks animation and their early work on the ComiColor cartoons.

One of my favorite stories so far in your wonderful Ink & Paint book, Ms. Johnson!

😀TY!

Paul Groh,

Thanks for the musical analysis. The music did sound familiar, but I could not place it. I hoped it would be in the credits—like Looney Toons did with _The Blue Danube_ and _Tales of the Vienna Woods_ as well as Hungarian Dance Number 2 — but it was not.

I thought of Danse Macabre, but I didn’t follow it up. Now I habe pieces to look up, review, and compare.

Thanks, Mr. Groh.

Ginny Jolly

You’re very welcome, Ginny!

While I like the idea, I’m not sure everyone would like to see Carl Stalling have the title of Disney Legend (a former writer of this site comes to mind).

Thanx Dan Lega.

Paul, you ought to start a blog devoted to cartoon music.

Now I need to know who that is, haha!

I wonder if Stalling’s career at Leon Schlesinger/Warner Bros influenced the decision not to award him Disney Legend status. However, common sense tells me that shouldn’t have been a problem.

Should it?

Rnigma: You’re very kind, but I have no desire to start a blog. I’m happy just to be part of the discussion on this one.

I would be remiss if I didn’t make a shameless observation that when I released THE LOST SKELETON OF CADAVRA in 2004, I attached SKELETON FROLIC to all the prints and noted its inclusion in the trailer and on the one-sheet. It was also a bonus on the original Sony DVD (now out of print). Being utterly anal-retentive, I added “Directed by UB IWERKS” to the prints, which had the reissue main title with no credits.

Yes, I’m sure “Lost Skeleton of Cadavra” is where my one copy of Skeleton Frolic came from, although it may have been available in one or two other places over the years. I had just pulled it up and indeed noticed the director credit overly on the title screen. It’s a similar cartoon in tone and theme, although rich color obviously and the animation has much more of that Iwerks Studio look (but it was a Columbia Color Rhapsody of course).

What is the instrument that is used for the bell at the beginning? I’ve heard Stalling use it in later cartoons, but mostly for single notes.

DGM, that instrument is a vibraphone. It resembles a xylophone or marimba, but with bars and resonators made of aluminium, and is likewise played with mallets. Between each bar and its corresponding resonator is a disc; these discs are connected to an axle that can be made to rotate by means of a motor, producing the characteristic vibrato or tremolo effect. I don’t know whether Stalling used it in any cartoon prior to “The Skeleton Dance”, but it was a brand new instrument at the time; the first commercially available vibraphone with motor and sustain pedal, known by the brand name “Vibraharp”, only came on the market in 1927. An actual bell probably wouldn’t have sounded spooky enough!

The vibraphone became a popular jazz instrument, whose most important exponent was Lionel Hampton. For a great Disney cartoon with a jazzy vibraphone solo, please see “The Plastics Inventor” (1944) starring Donald Duck.