Sheldon Moldoff pitch artwork. Click on image to see more.

Suspended Animation #348

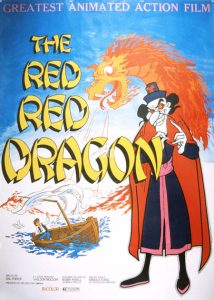

The Red, Red Dragon (also known as Marco Polo Jr. and even Marco Polo Junior Versus the Red Dragon) is officially classified as the first Australian animated feature film and was released in the country in 1972 but not released in the United States until 1973. It ran roughly 85 minutes.

The film was re-titled The Magic Medallion when it was broadcast on Australian television in 1976. Then it was sort of remade as Marco Polo: Return to Xanadu released by Tooniversal in 2001 that recycled some animation from the original film with thirty minutes of new animation sequences (produced in China and Slovakia) and eliminating much of the original story.

The storyline for the original was that Marco Polo Jr. with his companion seagull Sandy sets sail for Xanadu to reunite two halves of a magical medallion but during the quest, he must battle the evil ruler known as the “Red Dragon” who has imprisoned Princess Shining Moon who is the rightful heir to Xanadu’s throne. In the remake, the evil ruler is named “Foo-ling” and the Princess is named “Ming-Yu”.

The concept book for the film states, “Find the descendant of Marco Polo and you will find the key to the great Kublai Khan fortune…lost for over 700 centuries!” In the film the lead character is the seventh son of the seventh son of Marco Polo.

The film was a co-production between Australia’s Eric Porter Productions and an American company called Animation International Inc. headed by artist Sheldon Moldoff. Moldoff conceived of the idea for the film and had American artists Eli Bauer and Al Kouzel do some design work and storyboarding.

Moldoff drew many Golden Age comic books for DC including Hawkman. He spent roughly fifteen years as one of the “ghost artists” for Bob Kane on Batman stories including issues with the Zebra Batman and The Mermaid Batman as well as introducing characters including Batwoman and the original Batgirl.

In 1994, Moldoff recalled, “When (Courageous Cat and Minute Mouse) was greenlit, Kane came to me and said, ‘Shelly, I need storyboards and for you to write the stories’. I said I could handle it, and I did. But that was while I was still doing (anonymously the art for) Batman comic books.”

That limited experience sparked his interest in doing an animated feature film. Eric Porter Productions was the largest animation studio in Australia and in 1970 was producing roughly 800 television commercials a year and Porter wanted to do an animated feature. The year 1971 marked the 700th anniversary of Marco Polo’s original travels to China.

Moldoff had approached other international companies to produce his film but was unhappy with the sample animation they produced as well as the budget estimates. Porter negotiated a deal to co-produce the film, funding half of the film and then when it went over budget he had to contribute additional funds by using his personal savings and mortgaging his house.

Eric Porter with characters Princess Shining Moon (left),

Marco Polo Junior (right) and Sandy the Seagull (front).

In addition to being the co-producer, Porter was also the overall director. There was frequent correspondence between Porter and Moldoff with Porter every six months journeying to New York to show Moldoff the completed animation.

Both Porter and Moldoff insisted on being the sole creative force for the film. Moldoff always felt it was his film because it was his idea while Porter argued he was actually making the film and had made significant revisions to Moldoff’s script.

In the U.S., there was no mention of Porter except vaguely as the director and with the American release even that credit was often omitted. In Australia, they mostly ignored Moldoff except as a co-producing company that angered Moldoff considerably.

All the voices were recorded in New York. Voice talent for the film included: Bobby Rydell (Marco Polo Jr.), Arnold Stang (Delicate Dinosaur), Corie Sims (Princess), Kevin Golsby (voiced the Red Dragon when Hans Conreid became unavailable), Larry Best, Gordon Hammer, Lionel Wilson, Arthur Andersen, Merril Joels, Sam Gray. For the remake, all of the voices were recast so Tony Pope voiced Foo-ling and Nicholas Gonzalez as Marco Jr.

In a 1973 interview with Australian Woman’s Weekly, Golsby recalled, “I was the only Australian voice on the film. The rest of the cast were American to increase possible sales for the film. In terms of time, Marco Polo took me only four sessions over a period of two weeks to record. The Australian animators then took almost two years. In terms of enjoyment, however, it’s the high point of my career.

In a 1973 interview with Australian Woman’s Weekly, Golsby recalled, “I was the only Australian voice on the film. The rest of the cast were American to increase possible sales for the film. In terms of time, Marco Polo took me only four sessions over a period of two weeks to record. The Australian animators then took almost two years. In terms of enjoyment, however, it’s the high point of my career.

“My Red Dragon accent had to be evil with comic overtones. One minute he’s trying to convince everyone he’s really very nice to know and the next he’s calling on all his powers to destroy Marco Polo Junior so he can marry Princess Shining Moon and become emperor. I couldn’t talk for a couple of days afterwards.”

Animators included Jerry Grabner, Gairden Cooke, Stan Walker, Richard Jones, Paul McAdam, Ray Nowland, Dick Dunn, Wallace Logue, Yvonne Pearsall, Cynthia Leech, Vivienne Ray, Peter Luschwitz, George Youssef who all worked under sequence directors Cam Ford and Peter Gardiner.

Background work was by Graham Liney and Yvonne Perrin, sister of Eyvind Earle who was the prominent background artist on Disney’s animated feature Sleeping Beauty (1959). Monty Wedd did some storyboarding.

During production, Porter told The Australian newspaper, “This film will rate with Bambi and Pinocchio and other major cartoon features.” Ironically, Porter’s film would be released theatrically against Disney’s re-release of Pinocchio.

When the film premiered in Australia, there was very limited advertising and merchandising although several full color books were published by Sydney publisher Paul Hamlyn. No merchandising was produced for the American release.

In Australia, the film was pitted against not just Pinocchio but Bedknobs and Broomstricks, The Tales of Beatrix Potter, the re-release of Hoppity Goes to Town and Filmation’s Journey Back to Oz to name just a few holiday films. Porter had actually turned down the contract for the Filmation film to finish his Marco Polo project.

According to the publicity, the film included the following statistics: 114,578 frames were photographed, 7,500 feet of color film was produced, an estimated 160,000 hand-colored drawings were drawn of which of these, 54,279 were utilized for the film. Artists used 55 gallons of paint, 192 erasers and 6,996 pencils.

During production this 80-minute animated feature film had a production rate of about, on average, a minute and a half’s worth of footage produced per week. Here is a scene from the film:

Porter won the 1973 AFI (Australian Film Institute) Award for Best Director. Porter lost significant money on the production that affected his health and was one of the reasons for his studio’s demise. It has been suggested he was cheated out of income when the film was shown in the United States, especially for several years on Showtime.

In 2001, Moldoff stated, “My first experience with feature animation production was an unhappy one. Because of a very limited budget and some conflicts between the producers, the film turned out to be a terrible disappointment, especially to me.”

In 2015, the original version of the film was restored by the National Film and Sound Archives of Australia and released on DVD with a short documentary, The Making of Marco Polo Jr.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

The conflict between Eric Porter and Sheldon Moldoff was a major problem with “Marco Polo Jr.”, but not the only one. Another was the glut of Marco Polo movies released in the late ’60s and early ’70s, for example the Rankin/Bass musical “Marco!” starring Desi Arnaz Jr. as Marco Polo and Zero Mostel as Kublai Khan. (The casting is only one of the many ridiculous things about that incredibly ridiculous movie.) “Marco Polo Jr.” went through many title changes in the hopes of distinguishing it from all the other similar-sounding Marco Polo films that were coming out, but that had the effect of negating any name recognition the production might have had.

More to the point, a rival Australian animation studio called API made a feature titled “The Adventures of Marco Polo” that was broadcast on Australian TV just before the release of “Marco Polo Jr.” API made a lot of faithful but dull adaptations of classic stories like “Treasure Island” and “A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court”, which were shown on American TV on Saturday afternoons in the early ’70s. Their Marco Polo production was likewise rather dry and humourless, with somewhat limited animation (compounded by the fact that Australia didn’t start broadcasting television in colour until 1975). Widespread confusion between the television production and the highly-touted feature film adversely affected the latter’s box office.

It was long taken for granted in this country that specifically Australian stories and settings would not do well in the international market, but the success of the TV series “Skippy the Bush Kangaroo” in the late ’60s disproved this assumption. Compare the 1977 Yoram Gross animated feature “Dot and the Kangaroo” and its sequels, which grossed more internationally, cost less to make, and are much better remembered than “Marco Polo Jr.”