I would like to clear up the origins of one of the most beloved stars in Looney Tunes history, Foghorn Leghorn.

In late 1944, story man Warren Foster came up with a rooster story for Bob McKimson, recently promoted to a directing position and getting ready to begin his fourth cartoon. This story, eventually titled Walky Talky Hawky, ostensibly starred Henery Hawk, a tough-kid character originally created by Ted Pierce for Chuck Jones’s 1942 release The Squawkin’ Hawk. But it was obvious from the storyboard that Foster’s funny rooster would “steal” this cartoon.

In late 1944, story man Warren Foster came up with a rooster story for Bob McKimson, recently promoted to a directing position and getting ready to begin his fourth cartoon. This story, eventually titled Walky Talky Hawky, ostensibly starred Henery Hawk, a tough-kid character originally created by Ted Pierce for Chuck Jones’s 1942 release The Squawkin’ Hawk. But it was obvious from the storyboard that Foster’s funny rooster would “steal” this cartoon.

McKimson decided to base the loudmouth’s voice on a hard-of-hearing West Coast-only radio character from the 1930s, known simply as “The Sheriff”. Rather than using Mel Blanc (McKimson recalled he didn’t think Mel could do [that voice]), another actor was auditioned (frustratingly, I don’t know who this person was). But when that performer didn’t work out, Blanc came aboard and, McKimson recalled, “did a real good job.”

It is at this early point in the Foghorn saga that even Bob McKimson himself falls victim to the vagaries of recall, because by the time he began being interviewed in the mid-1970s (along with Clampett, Jones and many other Warner veterans), his memory was clouded by both the passage of time and the enormous fame that another old-time radio character, one Senator Claghorn, had enjoyed from 1945-49 on the highly respected comedy program The Fred Allen Show.

McKimson recalled telling Foster that he was listening to the radio and had heard Claghorn. He also believed that “Claghorn” had taken his vocal delivery from the old, deaf sheriff on the early variety show, Blue Monday Jamboree.

McKimson recalled telling Foster that he was listening to the radio and had heard Claghorn. He also believed that “Claghorn” had taken his vocal delivery from the old, deaf sheriff on the early variety show, Blue Monday Jamboree.

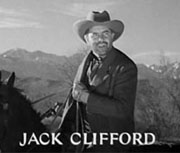

The Jamboree, like much of early West Coast radio, came out of San Francisco, before the show moved to Los Angeles in 1933, when network lines became operational in Los Angeles. At that point most of its cast began Hollywood acting careers, including character man Jack Clifford who originated “The Sheriff”. Clifford continued appearing as the Sheriff all through the 1930s on local LA programs like Comedy Stars of Hollywood, Komedy Kapers and The Gilmore Circus. He also played bit parts in many films.

The Sheriff – who would yell obnoxiously, talk over people, and repeat what he’d just said, prefacing each reiteration with “I say…” – was indeed the inspiration for Foghorn. But it must be emphasized, only for the first cartoon, Walky Talky Hawky. (Actually a major running gag for The Sheriff – bad puns based on mis-hearing what somebody was saying to him – was never a part of Foghorn Leghorn’s character.) But as McKimson mis-remembered it in his later years, he and Foster merged the two characters – the old sheriff and Senator Claghorn – and made them parts of the rooster.

But the plain fact is that the dialogue-track for Walky Talky Hawky was recorded on January 13, 1945, a full ten months before the debut of Senator Claghorn on Fred Allen’s New York-based show. A careful listen to this cartoon’s track reveals that Blanc sounds totally unlike the Foggy voice of the 1950s. Here he sounds much more like Yosemite Sam – loud and very gruff, and incorporating the Sheriff’s habit of starting a sentence and then re-starting with “I say…,” such as when the rooster yells, “Lose something – I say, didja lose something?” And the way he shouts “Pay attention, boy…”

But the plain fact is that the dialogue-track for Walky Talky Hawky was recorded on January 13, 1945, a full ten months before the debut of Senator Claghorn on Fred Allen’s New York-based show. A careful listen to this cartoon’s track reveals that Blanc sounds totally unlike the Foggy voice of the 1950s. Here he sounds much more like Yosemite Sam – loud and very gruff, and incorporating the Sheriff’s habit of starting a sentence and then re-starting with “I say…,” such as when the rooster yells, “Lose something – I say, didja lose something?” And the way he shouts “Pay attention, boy…”

Although a major influence on the cartoon, Jack Clifford’s Sheriff was virtually a forgotton local LA radio character by the time the cartoon was released in late August of 1946. But Senator Claghorn, ironically just ten months old, was already a national sensation.

Kenny Delmar (1910-84) was a highly successful New York-based radio actor and announcer. He began, like so many others of his era, performing in vaudeville (with his mother and aunt as The Delmar Sisters), before he broke into radio in 1936. An accomplished dialectician, he worked scores of East Coast shows like The Shadow where he met Orson Welles. Welles hired him in 1938 for his famous “War of the Worlds” broadcast, where Delmar, although playing “Secretary of the Interior,” imitated President Roosevelt’s voice and added to the reality feel that Welles was after. In the 1940s Delmar got the job of announcer for the prestigious, intelligent comedian Fred Allen.

In his late teens Delmar had hitchhiked cross-country and was given a two-day ride in Texas by a real-life character that every actor dreams about meeting. A bombastic rancher, this man would suddenly turn to his passenger and shout, “Son, I own five hundred head of cattle – five hundred, that is. I say, I own five hundred head of cattle.” He also insisted on finishing his wheezy gags with a hearty “That’s a joke, son! Ah say, that’s a joke!” Delmar stored this voice up in his mental computer and made him a party piece he called “Dynamite Gus.” After doing the voice briefly (as Counsellor Cartonbranch) on The Alan Young Show, a season before Young moved to the Coast in 1946, actress Minerva Pious – a long-time Allen supporting player – suggested Fred try Kenny’s windbag voice for the upcoming radio season.

Since 1942, a popular feature of Fred Allen’s radio show was Allen’s Alley wherein the star would wander down a make-believe street and meet a melting pot of Americana (Jewish housewife, a windy Irish-American, a New England farmer and a loudmouth politician). Jack Smart had been playing a pompous politico named Senator Bloat, but Smart had departed the show, and Allen had a hole to fill in his Alley.

So when Fred Allen returned to the air for the 1945-46 Fall season beginning October 5, 1945, his large national audience heard the Senator Claghorn voice for the first time.

Kenny Delmar and Fred Allen

The Senator’s chauvinistic Southern jokes (“I refuse to drink unless it’s in a Dixie cup!”) and catchphrases (“That’s a joke, son” and “That is”), bolstered by the strong comedy scripts written by Allen and his co-writers, became national bywords by the end of his first month, and all across Ameriac entranced listeners began imitating the Senator’s voice.

While Claghorn was proving an instant success, the second Foghorn Leghorn picture, Crowing Pains, was underway by late 1945, and on November 24, its dialogue was recorded. This was a full eight weeks after Claghorn had made his bow, and already some borrowing of his mannerisms begins. As mentioned above, it was Claghorn, not The Sheriff, who used the catch-phrase “That’s a joke, son,” and appended “that is” to various sentences, such as, “He was too short. Short, that is.”

So it was in fact this second entry that McKimson was thinking of when he recalled telling Warren Foster about the Claghorn voice (as he noted, Foster became very excited about the verbal gag possibilities). In Crowing Pains Foggy says, “That’s a joke, boy – ya missed it, went right past you!”And, most importantly showing the marriage of both The Sheriff and Senator Claghorn, “What’s the ga- I say, what’s the gag, son? Gag that is.” This cartoon was the start of Foster’s excellent use of the radio influences for the dialogue in the Foghorn cartoons, dialogue that by the early 1950s entries was often downright hilarious.

So it was in fact this second entry that McKimson was thinking of when he recalled telling Warren Foster about the Claghorn voice (as he noted, Foster became very excited about the verbal gag possibilities). In Crowing Pains Foggy says, “That’s a joke, boy – ya missed it, went right past you!”And, most importantly showing the marriage of both The Sheriff and Senator Claghorn, “What’s the ga- I say, what’s the gag, son? Gag that is.” This cartoon was the start of Foster’s excellent use of the radio influences for the dialogue in the Foghorn cartoons, dialogue that by the early 1950s entries was often downright hilarious.

A third rooster cartoon, Rootin’ Tootin’ Rooster began production in the summer of 1946. Its eventual title was The Foghorn Leghorn (the bellicose rooster, until then an anonymous barnyard denizen, finally took his name from this cartoon’s title). It was in this cartoon that the Senator Claghorn influence became truly blatant. Foggy says, “Scram. Scram, that is,” “Lookee here, son,” and employs the actual Senatorial standby, “That’s a joke, son…a flagwaver….”

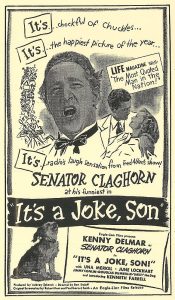

Meanwhile, following his first season with Fred Allen, Kenny Delmar was wooed to Hollywood to make a feature film starring the highly popular Senator. The movie was called – what else? – It’s a Joke, Son! (it was filmed in mid-1946, while the Allen show was on summer hiatus, and released in early 1947. Interestingly the third Foghorn cartoon’s dialogue was recorded in late July and early August, while Delmar was shooting his movie nearby). Delmar remained with Fred Allen until Allen’s final show in June 1949, at which point the Senator’s fabled radio career ended after four very successful years. (Of course he continued doing the Senator for years in commercials, and even played a similar Southern politician on Broadway in a production of Texas, Li’l Darlin’).

Meanwhile, following his first season with Fred Allen, Kenny Delmar was wooed to Hollywood to make a feature film starring the highly popular Senator. The movie was called – what else? – It’s a Joke, Son! (it was filmed in mid-1946, while the Allen show was on summer hiatus, and released in early 1947. Interestingly the third Foghorn cartoon’s dialogue was recorded in late July and early August, while Delmar was shooting his movie nearby). Delmar remained with Fred Allen until Allen’s final show in June 1949, at which point the Senator’s fabled radio career ended after four very successful years. (Of course he continued doing the Senator for years in commercials, and even played a similar Southern politician on Broadway in a production of Texas, Li’l Darlin’).

And as for Foghorn Leghorn, his character – refined a little more film by film – went on into the 1950s and early 60s in a highly successful series of cartoons. Interestingly, a new supporting hen, Miss Prissy, was also lifted virtually intact from another New York-originated radio character on The Milton Berle Show, that of a dizzy rich woman whose answer to everything was an imperious, vacuous “Yeeeesss” – she was played by Pert Kelton, an early TV foil of Jackie Gleason.

I trust this clears up some misconceptions. The legend of Foggy’s origins has been, at best, semi-accurate and clouded in vagueness, but the facts show a different story, and there is simply too much animation studio history that is only semi-accurate or, even worse, totally wrong.

Copyright ©2013/2023 by Keith Scott

Keith Scott is a voice actor, impressionist and animation historian. Scott provided the voice for Bullwinkle J. Moose in the 2000 motion picture The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (for which he had been specially flown to the United States several times) and did the voice of the narrator in George of the Jungle and George of the Jungle 2. An expert on the history of Jay Ward Productions, Keith authored the book The Moose That Roared: The Story of Jay Ward, Bill Scott, a Flying Squirrel, and a Talking Moose (St. Martin’s Press, 2000).

Keith Scott is a voice actor, impressionist and animation historian. Scott provided the voice for Bullwinkle J. Moose in the 2000 motion picture The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (for which he had been specially flown to the United States several times) and did the voice of the narrator in George of the Jungle and George of the Jungle 2. An expert on the history of Jay Ward Productions, Keith authored the book The Moose That Roared: The Story of Jay Ward, Bill Scott, a Flying Squirrel, and a Talking Moose (St. Martin’s Press, 2000).

wow! It’s like when the young me discovered Old Time Radio, and that there was more to the cartoons than I knew. There is more to the more to it than I knew. That there is a breed of leghorn chicken to provide wordplay on the Senator’s name shows that it was supernaturally meant to be — meant to be, that is.

Pert Kelton is even better remembered as “Widow Paroo”, the mother of librarian Marian in both the stage and film versions of “The Music Man”.

Crowing Pains is prominently in the discussion when compiling a Top Ten Warner Toons list.

Of Mice and Magic says that McKimson’s cartoons were “unquestionably the weakest entries in the Warner’s output.” I 100% disagree with that as without McKimson directing, we wouldn’t have Foghorn Leghorn.

They are (by far) the weakest. But many of them are great.

Compared to the shorts from the other units, they are AT LEAST lower grade, but not weak. The early McKimson shorts are definitely his strongest efforts while his later shorts are not AS good, but still quite fun.

So Foghorn Leghorn is an amalgam of Jack Clifford’s old sheriff — who ostensibly was not a specifically Southern character — and the Texas rancher whose voice Kenny Delmar adapted into that of Senator Claghorn after Jack Smart left the Fred Allen show.

Out of curiosity I did a quick Google search for “Foghorn Leghorn accent” and was amused, though not altogether surprised, to find a widespread consensus that Foggy has a Central Virginia accent! There are an awful lot of latter-day Henry Higginses out there who believe that every Southern state has dozens of mutually distinct and recognisable accents, and that they can identify every single one of them. And they really can — incorrectly, that is.

My father went to school with Sorrell Booke, the actor who played Boss Hogg on “The Dukes of Hazzard”. Once he told us about meeting a fan of the show who insisted he could identify the exact county in Georgia where Sorrell was from, purely on the basis of the accent he used in the show. When Dad told him that Sorrell grew up on the East Side of Buffalo, and that he and his family used to walk past my dad’s house every Friday on their way to temple, the guy flat out refused to believe him.

It’s not only animation studio history that is “only semi-accurate or, even worse, totally wrong.” Thanks for setting the record straight.

Before the Allen’s Alley feature took over, Allen had a regular interview segment on his program, including a conversation with Superman creator Jerry Seigel. While supposedly off the cuff, these talks were actually fully scripted by a young Herman Wouk. The Alley was a way of standardizing the interview format rather than trying to find someone new each week, and employed seasoned performers instead of actual guests who frequently delivered clumsy readings of their prewritten remarks. In one of the later Alley visits, Allen quipped that “Someone must be pulling the Senator’s legbone.”

Allen said “Leghorn,” not “legbone.” SpellCheck is like a joke-teller who always blows the punch line.

I read once somewhere that Mel Blanc found Yosemite Sam the hardest voice to do, because he basically had to yell all the time. I wonder if Foghorn Leghorn was similarly painful.

(Does Keith Scott’s book come with one of those old-time CDs, or a website with samples of the voices he writes about?)

No.

I must have missed this column, ’cause it is new to me!

People’s memories of things that happened decades earlier seem to be always cloudy and not entirely accurate. I’ve learned that in not “fact checking” interviews with old Hollywood stars and classic cartoon animators is a bad mistake. So, I’ve tried to do research and sometimes – if I’m lucky enough – I’ve been able to re-contact the person I’ve interviewed and have the person either retract the information, or add to it, clarifying the facts a lot more. Sometimes, the late Jackson Beck would stubbornly insist that he was right or he’d admit he was mistaken and suddenly remember something important to add onto what he had told me. I wish I had been able to get a “three party” phone hook-up when I interviewed Dave Tendlar on the phone so that he could talk to Gordon Sheehan – but sometimes things can’t happen that way. I’m glad we’ve got people like Keith Scott who is able to do lots of detective work on all this animation history!

This post and the post Keith wrote into phoney claims of Mel Blanc’s “exclusive voice credit” are two must-reads on this site by anyone into old animation.

Despite Keith’s work documenting facts, people still go on-line spouting wrong information.

Paul’s observation is too typical. Some people believe what they want to believe, and won’t accept being wrong, despite indisputable evidence to the contrary.

After years, I finally heard the sheriff on one of the 15-minute syndicated shows from Los Angeles. I wish I had bookmarked it.

Delmar and Parker Fennelly took their Alley characters, changed their names, and appeared on CBS radio’s “Funny Side Up” around 1959.

It would seem to me that the reason most people went straight to Kenny Delmar as the sole basis for the character would the NAME… FogHORN LegHORN/ Senator ClagHORN…

Great info! Which character was funnier? The Sheriff or Senator Claghorn. Kenny Delmar’s Claghorn has made me laugh out loud. Foghorn never has.

I’ll admit that Foggy has made me laugh — but not nearly as much as your cartoons have, Tom!

Kenny Delmar did a number of funny voices for Total Television Productions, notably Commander McBragg, Major Minor (Klondike Kat), The Hunter, and Colonel Kit Coyote (Go Go Gophers). He also voiced several minor characters from Tennessee Tuxedo (Yak, Baldy Eagle, Flunky, Tiger Tornado).