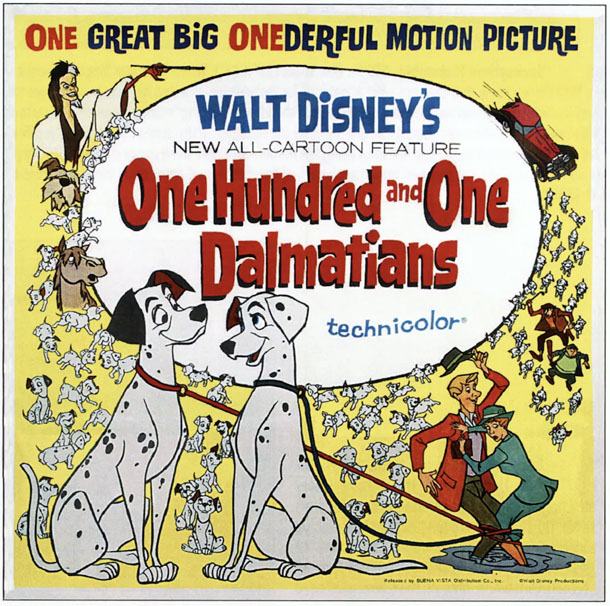

When Walt Disney’s One Hundred and One Dalmatians opened on January 25, 1961, it was a “first” in so many ways.

For the first time, a Disney animated feature would have a contemporary setting; it would also be the first “non-musical” animated feature to come from the Studio and the first time Disney was using a new technical process to produce an animated film.

All of these “firsts” came together to create film that, sixty-plus years after its debut, is still regarded as one of Disney’s best and most beloved.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians came to life as a film at Disney as an antidote to all that was Sleeping Beauty (1959), the last animated feature made just prior, which had consumed a tremendous amount of time and money. There was a need to create a story that would be easier to execute in many ways.

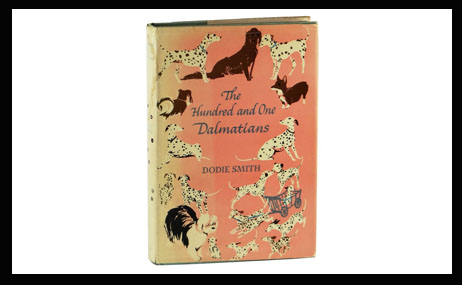

In 1957, Walt Disney purchased the rights to the novel, The Hundred and One Dalmatians by Dodie Smith, which had been published the year prior.

Walt gave the book to story artist Bill Peet and tasked him with writing a screenplay, before any storyboarding would be done (another first for Disney!).

In Bill Peet: An Autobiography, the artist remembered:

“Walt wanted me to plan the whole thing: write a detailed screenplay, do all the story boards, and record voices for all the characters. That had been a job for at least forty people on Pinocchio in 1938, but if Walt thought I could do it, then of course there was no question about it.”

Some changes were made from the original book, but the essential elements were still there, as One Hundred and One Dalmatians would focus on a Dalmatian “husband and wife” named Pongo and Perdita and their “pet humans,” husband and wife Roger and Anita, as they await Perdita’s delivery of their litter of puppies.

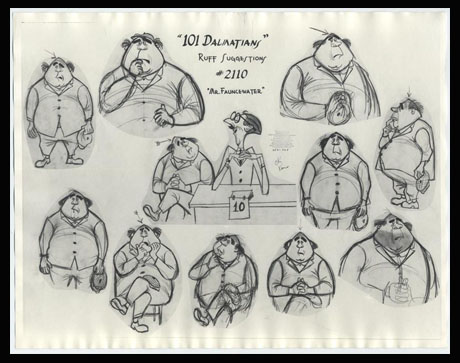

Anita’s former school-mate, Cruella De Vil, then emerges – all sharp edges, black-and-white hair, reed frame and billowing cigarette smoke – looking to “adopt” the puppies. In actuality, she is looking to make a spotted dalmatian fur coat (!)

Cruella hires two dim-witted henchmen, Jasper and Horace to kidnap Pongo and Perdita’s fifteen puppies, which they do. With the assistance of neighborly fellow canines (through an inventive sequence where they initiate “The Twilight Bark”), Pongo and Perdita run away from home and find their puppies at Cruella’s dilapidated “lair,” along with a slew of other dalmatian puppies (101 to be exact!).

As Pongo, Perdita and all of the puppies make their way back home, they are pursued by Cruella, Horace and Jasper, resulting in an ingeniously animated and very exiting car-chase sequence. Do they all make it home to Roger and Anita? If you haven’t had the chance to see the film in six decades, there will be no spoilers here.

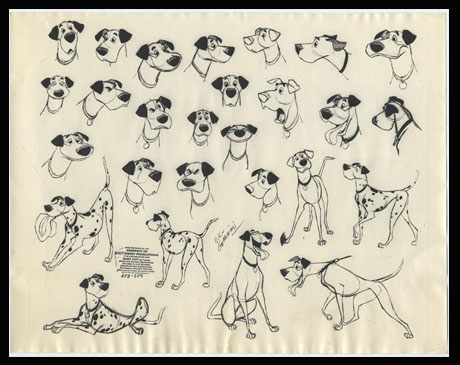

In addition to the story, one unique aspect (and yet another first) to One Hundred and One Dalmatians was the look of the film. As the artists had seen while bringing the rich, epic Sleeping Beauty to life, the Studio’s animated films were taking a tremendous amount of time and money to produce.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians would be smaller in scale, which would make it somewhat easier to produce, but there would still be the task of drawing and animating spots on the Dalmatians…a lot of them. In fact, the grand total number of spots that were animated in the film were: 6,469,952!

To accomplish this, the Disney artists initiated a new process called Xerography, which would allow an animated film to be produced quicker. In this process, the filmmakers were able to directly copy the animator’s original drawings onto animation cels, saving time and money and also preserve the animator’s original drawings, as much as possible.

This made all of those spots so much easier and less tedious to draw and animate, however, it created a look that was very different for a Disney film. The character’s look wouldn’t be as “refined” or “soft” as it had been in previous Disney animated features. Now, the characters would take on much more of a “rougher, sketchier” appearance.

To allow this look to be more at home, Ken Anderson, the art director of One Hundred and One Dalmatians, created backgrounds that were much “looser” in their appearance. Inspired by cartoonist Ronald Searle, the backgrounds took on a contemporary style that would go along with the setting of the film. Here, color would “bleed” outside the line of buildings and props, looking more like modern art, than traditional Disney background paintings.

This style was very prevalent in animation at the time, being first introduced by United Productions of America (UPA Studios) and was seen in almost all of the TV animation done at the time.

Walt, however, was not a fan. He did not care for the more stylized animation and, as author Michael Barrier states in his book Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in its Golden Age, Walt didn’t like the bold, black lines that appeared around the characters in the film (as well as a number of the backgrounds).

Barrier writes:

“However harmonious the result on the screen, Disney knew that it was a step away from the kind of illusion that more traditional backgrounds-and devices like the now dormant multiplane camera-had once furthered.”

Aside from the modern look, the contemporary setting allowed for some pointed satire in One Hundred and One Dalmatians, the likes of which hadn’t been before in a Disney animated feature. This is most prevalent in the sequences in which the Dalmatians watch television. The Thunderbolt TV Show, sponsored by “Canine Crunchies,” is a direct jab at the commercial aspect of television and Horace and Jasper watching What’s My Crime? parodies What’s My Line? and other ubiquitous game shows of the time.

Many criticized these scenes through the years, feeling that it takes away the timeless feel that most animated films from Disney had and “dates” One Hundred and One Dalmatians. While this may have been true in the decade or so that followed the film, it now gives it more of a sense of a “period piece.”

A more traditional element in One Hundred and One Dalmatians is that of the Disney villain…and with this film, audiences got if not the most, then one of the most memorable villains of all time.

Cruella De Vil has become an iconic example of what we expect from one of the Studio’s villains. She was created, designed and animated by Disney Legend Marc Davis, a member of Disney’s “Nine Old Men,” the title Walt had given to his upper echelon of animators.

After bringing to the screen such dynamic characters as Tinker Bell in 1953’s Peter Pan and Maleficent and Princess Aurora in Sleeping Beauty, Cruella emerged as Davis’ crowning achievement. The epitome of true personality animation, his work on Cruella is still, rightfully, studied to this very day.

“She’s fascinating to watch,” said animation historian and author John Canemaker of Cruella in a 1998 interview. “She moved in this angular, aggressive way. She’s all over the place, almost like a force of nature. You don’t like her as a person, although you love her as a character.”

When One Hundred and One Dalmatians debuted in theaters, it was an immediate hit with audiences and critics, grossing $14 million in the U.S. and becoming the eighth highest grossing film of the year. Ironically, the success of the film helped ease some of the financial burden of Sleeping Beauty.

The film was re-issued theatrically in 1969, 1979, 1985 and 1991. During its last re-issue in ’91, One Hundred and One Dalmatians went on to become the 20th highest grossing film that year.

The impact of the film has been such that it was the first Disney animated feature to be re-made in live-action (something commonplace today) in 1996 with Glenn Close turning in a wonderful performance as Cruella. The live-action re-make spawned a sequel, 102 Dalmatians in 2000.

There was also an animated TV Series that ran on ABC from 1997-1998. And, in 2011, Cruella, a live-action, “origin story” of sorts about a young Cruella De Vil, with Emma Stone.

Like many of Disney’s most beloved films, this demonstrates the continued impact of One Hundred and One Dalmatians. This “first” in so many ways has definitely had a lasting impact.

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

The book by Dodie Smith is a must-read for anyone who appreciates British whimsy in the vein of Mary Poppins or the Chronicles of Narnia. There are many differences from the Disney film, such as the character of Perdita, who is different from Mrs. Pongo in the book. She is brought in as a sort of wet nurse to help wean the original litter of 15. She has a different backstory, as well, which ultimately ties into the conclusion. My favorite part of the book, which of course couldn’t have been worked into the film without breaking the continuity, is a Christmas scene in a church in which one of the dogs views a Nativity scene and believes it to be a television–and makes an indelible impression. It’s best to view the film first, and then read the book, as the book expands and further illuminates themes that are only touched upon in the film.

One Hundred and One Dalmatians is also the first Disney animated feature to use Hitchcock-like suspense. The scenes of the dogs trying to escape the Badun brothers are fraught with tension as well as comic relief. Those sequences alone are a tour-de-force of suspense balanced with humor.

As for Cruella, she is one of the all-time classic Disney villainesses. She is both a figure of menace and comedy at the same time. I was always fascinated by how skinny she was underneath that massive fur coat.

Greg Ehrbar has written an excellent discourse on the Disneyland Records version, which recording offers a few more variants on the screenplay and is a work of art in its own right.

I can’t judge 101 Dalmatians, as it was the first movie I ever saw in a theater, at age 5.

But it’s good to know it’s so highly thought of. This toddler loved it!

This film is one of my earliest Disney memories, as at five years old my Dad took me to see the 1991 reissue (how I wish Disney still did that on a wide scale!) and he explained how theaters show movies multiple times a day. He opened the door to show me how one group of people was watching the film now and then it would be our turn and it so happened the moment where Cruella and the Bad’uns wreck their vehicles was on the screen. Once seen, never forgotten!

Perhaps it’s presumptuous, but after the wreck, once Cruella and the boys are sitting by the roadside (‘Ahhh, shaddap!!’) I imagined a bit of a contiuation of the scene with a pair of constables pulling up in a police car (having been alerted by the Dinsford mechanic who got suspicious of the commotion Cruella raised as the moving van was pulling out):

Constable 1: ‘Ello ‘ello ‘ello? And what have we here?’

Constable 2: ‘Gone for a Sunday drive, have we?’

(As the villains exchanged defeated looks) Horace: ‘Uh Jasper, I’ve been thinking….’

Fade out.

101 Dalmatians wouldn’t place in my top ten Disney films but it’s definitely in my top 20 or 30. I actually thought the rougher look was fine for this film- it was The Sword in the Stone, Robin Hood and ESPECIALLY The Rescuers where it was distracting.

The self-congratulatory Disney books extol the use of different colored toners in “The Rescuers,” which they felt somehow increased the integrity of the still-scratchy Xerographed line. At times the gray toner only separated the characters from the backgrounds. But at least they’d gotten better at erasing the construction lines by then.

Another first is the use of actual children’s voices for the puppies. Children’s voices had been used in animated commercials and some UPA shorts, but Disney seemed to go specifically for cute lisping little voices (presumably believing the mothers in the audience would find them adorable), ultimately influencing Don Bluth.

What an unusual trailer–No loud, hard-sell voiceover declaring this feature Disney’s most tune-filled, smilingest, hap-hap-happiest ever. Dick Tufeld must have been on vacay that week.

Am I the only one who felt the one false note in the entire film was Cruella surviving that horrific collision near the end without so much as a scratch (while the Cruellamobile was completely totaled)? Really took me aback when I was a young ‘un. (as opposed to a Badun). Yeah, yeah, it’s “just a cartoon”.

According to a Disney mini documentary I watched, tall, angular Mary Wickes was the live action model for wicked Cruella De Vil. It showed photos of Mary in the De Vil outfit.

The prolific character actress made 40 films (White Christmas, Sister Act) and was a regular on Make Room For Daddy, Dennis the Menace and many other TV series.

Mary Wickes was also in the Mickey Mouse Club serial “Annette” with fellow sitcom regulars Richard Deacon and Doris Packer; she may have done her live-action modelling for Cruella concurrently with that role. Her final role was voicing Laverne in Disney’s “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”.

Another note is how they solved the Prince Charming problem. After years of handsome, posing cyphers opposite fairy tale princesses, Roger is a plausible romantic lead while being a solid comic character. The less flamboyant Anita, meanwhile, is also something new: neither dewy innocent nor maternal old lady, she’s an appealing adult woman who can play well with both the gangly Roger and outrageous Cruella.

“101 Dalmatians” wasn’t the first animated Disney feature with a contemporary setting. “Dumbo” was.

I know an awful lot of people love this movie, and I’m happy for them, but personally I agree with Walt Disney. I’m more of a “Sleeping Beauty” guy myself.

Great job, Michael! I first saw “101 Dalmatians” at age 7 in a theater during its 1969 re-release, and I now consider it my favorite fully animated feature regardless of studio. And it’s my second favorite Disney film, behind only “Mary Poppins.” I particularly love those UPA-style backgrounds and color stylings. Plus, I’m just a sucker for snowy landscapes.

Thanks so much Kevin! Glad you enjoyed it!

It is a fantastic movie, one of animation’s greatest. It is authentically funny, well-told, and brilliantly animated. I’m sad Walt didn’t like it.

I love the opening title sequence to this movie!

I remember Chuck Jones saying at the time, “Only Disney would do a film with 101 spotted dogs. We have trouble making a film with ONE spotted dog.”