Stephen Bosustow in 1957

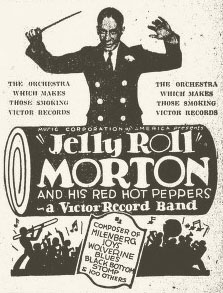

Animators had embraced African American jazz for decades by then. Most famously, Max Fleischer cast Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, and the Mills Brothers in cartoons in the early 1930s, and Hugh Harman hired African American musicians to lampoon those celebrities for his jazz-frog cartoons of the late 1930s. Bosustow himself was no stranger to marrying jazz with animation; his UPA cartoon Rooty Toot Toot, directed by John Hubley, featured a score by musician Phil Moore. In fact, the Pittsburgh Courier of January 24th, 1953 reported that London’s music periodical Melody Maker named Moore’s score “the best jazz music in a film in 1952.”

The 1959 article does not provide any reasons why Bosustow started the Morton film. It merely cites him as wanting to produce “a serious motion picture told in cartoon.” However, he laid out a plan for it that depended on the successes of other projects–namely, two features starring UPA’s flagship character Mister Magoo. If the public responded well to 1001 Arabian Nights, then Bosustow would have followed it with another comedic adaptation of folklore–Robin Hood Magoo. After that film would have come the serious Morton movie–without Magoo. “We already have five minutes of scenes completed with jazz ready for the picture,” the producer bragged to the Courier.

The 1959 article does not provide any reasons why Bosustow started the Morton film. It merely cites him as wanting to produce “a serious motion picture told in cartoon.” However, he laid out a plan for it that depended on the successes of other projects–namely, two features starring UPA’s flagship character Mister Magoo. If the public responded well to 1001 Arabian Nights, then Bosustow would have followed it with another comedic adaptation of folklore–Robin Hood Magoo. After that film would have come the serious Morton movie–without Magoo. “We already have five minutes of scenes completed with jazz ready for the picture,” the producer bragged to the Courier.

The announcement of the Morton biopic adds a twist to Bosustow’s speech at the segregated Tulane. He apparently began work on the film after the speech. He had given his address on December 11, 1959, but the Courier’s article of December 26 mentioned that he “started his chores last week,” which would have been December 18 at the earliest. The separate interests of the press outlets also add to this twist. The Pittsburgh Courier was a newspaper established by African Americans for an African American readership, and it did not mention Bosustow’s Tulane remarks. On the other hand, none of New Orleans’s mainstream periodicals like the Times-Picayune relayed his announcement about the Morton film.

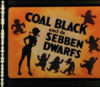

The project was risky for several reasons. Movies starring African Americans had hit-or-miss track records; Porgy and Bess had mixed reviews in 1959. African American biopics were even rarer. In addition, animation studios steered clear of depictions of African Americans by this time. Civil rights organizations pressured distributors to pull cartoons with stereotyped characters from theaters, and television networks had already begun censoring old cartoons with those images. Aside from an appearance by Eddie “Rochester” Anderson in The Mouse That Jack Built that year, the African American cartoon character was a thing of the past. The Courier had publicized protests against many cartoons like Chuck Jones’s Angel Puss and Tex Avery’s Uncle Tom’s Cabana; the newspaper’s willingness to promote Bosustow’s project showed a high level of trust in the seriousness he promised for the film.

The project was risky for several reasons. Movies starring African Americans had hit-or-miss track records; Porgy and Bess had mixed reviews in 1959. African American biopics were even rarer. In addition, animation studios steered clear of depictions of African Americans by this time. Civil rights organizations pressured distributors to pull cartoons with stereotyped characters from theaters, and television networks had already begun censoring old cartoons with those images. Aside from an appearance by Eddie “Rochester” Anderson in The Mouse That Jack Built that year, the African American cartoon character was a thing of the past. The Courier had publicized protests against many cartoons like Chuck Jones’s Angel Puss and Tex Avery’s Uncle Tom’s Cabana; the newspaper’s willingness to promote Bosustow’s project showed a high level of trust in the seriousness he promised for the film.

The Courier’s report on Bosustow’s research unfortunately coincided with a major transition at UPA. Columbia Pictures stopped distributing the studio’s films to theaters after the failure of 1001 Arabian Nights, and Robin Hood Magoo never played in theaters. In 1960 Bosustow sold the studio to Henry Saperstein, who then committed UPA to television. When the studio made one last feature two years later, the featured musicians were singers Robert Goulet and Judy Garland–a drastically different musical direction from Jelly Roll Morton–for Gay Purr-ee. That movie did not fare well either; perhaps those five minutes of Morton-inspired animation would have helped.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

Christopher P. Lehman is a professor of ethnic studies at St. Cloud State University in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His books include American Animated Cartoons of the Vietnam Era and The Colored Cartoon, and he has been a visiting fellow at Harvard University.

This is interesting. Too bad that this project never saw the light of day, but I thought that the Hubleys produced a cartoon or two with a jazz score and images that positively linked with the music, but I’ll leave that to others to research. UPA was always striving to enhance the art of animation, to bring it beyond what it was always perceived as, and that is still difficult in these times. Yet the studio will always be remembered for its series titles like MR. MAGOO and DICK TRACY. It’s a shame, too, because, at that time, there was a lot of very expressive jazz out there that would make terrific soundtracks for cartoons with something relevant to the times to say.

That’s too bad. I always felt Morton’s life and career would have made one helluva movie. Whether animated or live action.

“African American biopics were even rarer.”

Yes… but Paramount had recently produced such a rarity: ST. LOUIS BLUES (1958), with Nat “King” Cole as W.C. Handy and an outstanding cast including Pearl Bailey, Cab Calloway, Eartha Kitt, Mahalia Jackson and Ella Fitzgerald. It was even filmed in VistaVision. There were a lot of musical biopics in the ’50s (THE GLENN MILLER STORY had been an enormous hit for Universal), and I’m glad Cole was given the opportunity to play Handy in this. The movie isn’t quite the sum of its parts, but it’s worth seeing.

This may explain why the Robin Hood installment of “The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo” spanned 4 episodes, when the rest of the series was made up of one and two-parters. I’m guessing the screenplay was adapted from notes for the projected theatrical feature film.

The Morton project sounds fascinating and might have made an amazing feature film.

Musical director Lyn Murray makes reference to this in his autobiography, remarking that he was assigned by Steve Bosustow to do research for a possible Jelly Roll Morton biopic, based on Alan Lomax’s book about Morton. Murray wrote that he found it interesting but didn’t think there was a picture in it.

Morton’s life did eventually become a Broadway musical, “Jelly’s Last Jam”, and Gregory Hines won a Tony playing Morton. It takes a fantasy approach: Morton, after death, is led through his life by a mystery man. Perhaps the UPA version would have taken a non-literal approach as well.

I’d read that UPA originally wanted to do “Don Quixote” with Magoo, but went with “1001 Arabian Nights” because a Columbia executive never heard of Quixote. In the end “Don Quixote” was also adapted for the TV series, but strangely as one freestanding episode followed later by a sort of sequel. To my mind hard to imagine anything salvaged from a screenplay.

Magoo’s version and the Broadway musical “Man of La Mancha” both appeared in ’64 and it seems unlikely either was influenced by the other (very little overlap in what each took from Cervantes). The musical set the idea of Quixote as a mad romantic idealist; Magoo’s was a likable comic fool. Does a movie treatment of Magoo’s Quixote survive?

Always thought “Man of La Mancha” was a candidate for animation. The stage version fuses fantasy and reality as a play within a play; when Cervantes plays the character to entertain fellow prisoners of the Inquisition, he is just as much a knight as a crazy old man. The movie jumps between Cervantes in prison and mad Quixote in the real world; Quixote’s fantasy is never seen. In animation the various worlds — prison, countryside and world of knights and giants — might be stylistically or abstractly fused in a way film cannot attempt.

I suppose it’s one of those “What-ifs” that never came to pass. There would be however animated TV adaptations of Don Quixote that have been done in various qualities and quantities in the decades that followed. I’m reminded of one produced in Spain around the late 70’s with a disco-ish opening theme song but a rather serious take on the original novels that follow.

Making a movie on Morton’s life would have been extremely difficult in any medium. Morton was one of the pioneers in the development of jazz, but his greatest claim to fame was as an arranger. That may not sound too important but back then jazz was totally improvised. Nothing was written down. Turn of the century standards were learned by rote by musicians.

When Morton began committing these tunes to paper, it was considered heresy among the old guard.

That premise works just fine in a documentary like Ken Burns ‘JAZZ’, but it becomes tough sledding in a dramatic film. Not to mention the fact that in real life Morton was an arrogant, self-serving SOB. So there goes the underdog factor.

When Steve Bostustow opened his own animation studio (we need to talk about this studio here) after UPA changed hands, did he have any renewed interest on doing the Morton project?