Bill Nolan was not only born to animate, he was integral to birthing the industry. Raised in Connecticut, William Charles Nolan spent his summers at the Jersey shore, staying with relatives in the resort town of Long Branch.

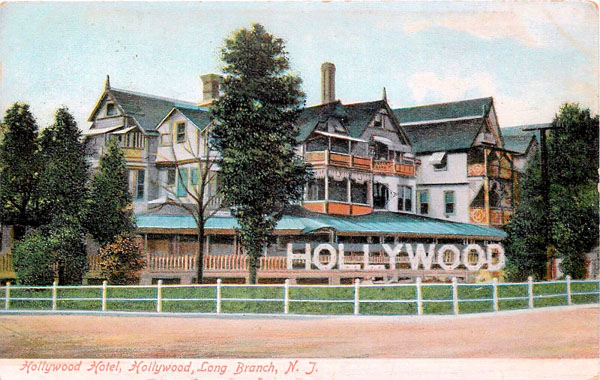

Long Branch was a favored warm-weather destination of people in the entertainment biz. Bill Nolan was six years old in 1900 when Broadway’s finest left New York as the mercury climbed. Producers, directors, actors, writers, and artists swarmed to Long Branch’s many fine hotels, mingling with the vaudeville crowd as they all splashed about in the Atlantic Ocean. With the new century rolling in motion picture people joined the mix, some staying at Long Branch’s Hollywood Hotel.

Long Branch was a favored warm-weather destination of people in the entertainment biz. Bill Nolan was six years old in 1900 when Broadway’s finest left New York as the mercury climbed. Producers, directors, actors, writers, and artists swarmed to Long Branch’s many fine hotels, mingling with the vaudeville crowd as they all splashed about in the Atlantic Ocean. With the new century rolling in motion picture people joined the mix, some staying at Long Branch’s Hollywood Hotel.

During 1913 Bill Nolan was already illustrating for a newspaper in Connecticut when he decided to take up residence in Long Branch. Newspaper cartoonist Raoul Barré vacationed there that year. Raoul Barré was well known in his native Canada, and a rising star in America. He’d just come off an assignment for a guy named John Bray. Barré had been hired to help Bray complete a long series of drawings, which were then photographed to portraymovement, Winsor McCay had released a couple such films, and the Universal Motion Picture Manufacturing Corporation delved into the idea at their Fort Lee studio. Opportunity knocked, and Bill Nolan happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Raoul Barré convinced Thomas Edison to lease him space at a film processing lab on Decatur Avenue in the Bronx. Bill Nola went with him. Barré soon moved into larger quarters a block away on the top floor of the two-story Fordham Arcade Building, hiring Frank Moser, Gregory LaCava, and Ben Harrison. Just as things were running smoothly, William Randolph Hearst offered bigger paychecks and poached Barré’s top people. Nolan, Moser, and LaCava went to 729 Seventh Avenue in Manhattan to animate theatrical cartoons for Hearst. Ben Harrison stayed with Barré.

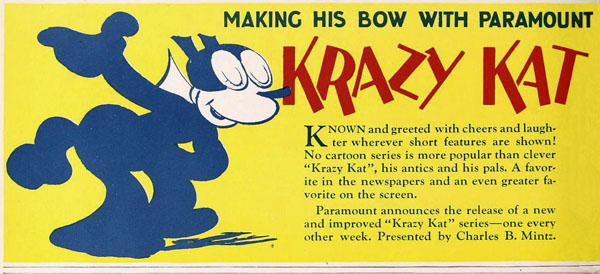

Hearst’s cartoons were based on comic strip characters from his newspapers. Bill Nolan worked on the KRAZY KAT series, among others. Those cartoons followed the general premise of creator George Herriman’s strip. Krazy, an innocent-minded female cat is hopelessly in love with Ignatz, a sadistic mouse.

Gregory LaCava brought art school friend Grim Natwick in. Bill Nolan and Grim Natwick became fast friends. Hearst stopped production in 1918 and the crew disbanded. LaCava found success directing movies in Hollywood. Grim Natwick painted sheet music covers. Nolan probably returned to newspaper illustration. Moser alternated between Raoul Barré’s studio and one opened by John Bray.

Barré kept his doors open by making MUTT AND JEFF cartoons with his new partner Charley Bowers. Ben Harrison was still there, becoming thick as thieves with animator Manny Gould. Long story here for another time. Short version: Barré threatened to shoot Bowers for swindling him and ended up under psychiatric observation while Bowers seized control of the studio. Harrison and Gould stayed to ride the Bowers train.

Hearst licensed KRAZY KAT and other properties to Bray Studios in 1920. Bill Nolan and Grim Natwick reunited as they worked beside Bray’s animators Jack King and Walter Lantz. That gig ended in 1921. Natwick went to Europe, studying art in Austria. Nolan seems to have been out of the animation game again. He was already a legend in the industry for having promoted the “rubber hose” style and engineering pan-shotbackgrounds. Bill Nolan’s speed with a pencil was matched by few animators. One was said to be Otto Messmer at Pat Sullivan Productions.

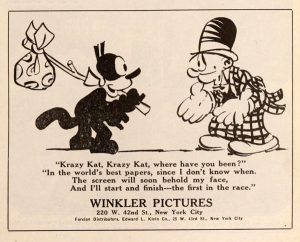

Bill Nolan surfaces again in 1924 at Pat Sullivan Productions, where he redesigned Felix the Cat. The quality of FELIX THE CAT cartoons improved, increasing the character’s already stellar popularity. Jack Carr, former cartoonist for the New York GLOBE, animated FELIX THE CAT with Nolan. Those films were released through a distribution company controlled by Charles Mintz.

Bill Nolan surfaces again in 1924 at Pat Sullivan Productions, where he redesigned Felix the Cat. The quality of FELIX THE CAT cartoons improved, increasing the character’s already stellar popularity. Jack Carr, former cartoonist for the New York GLOBE, animated FELIX THE CAT with Nolan. Those films were released through a distribution company controlled by Charles Mintz.

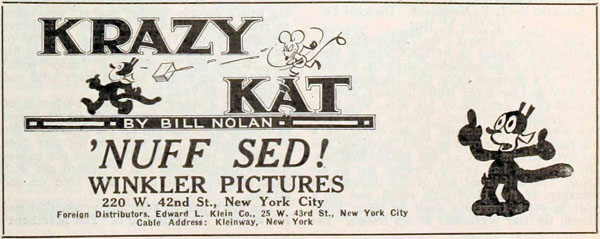

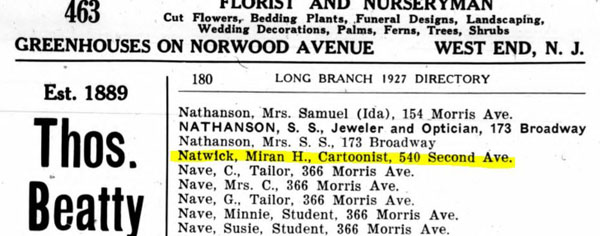

Bill Nolan and Charles Mintz made a deal. Mintz secured rights from Hearst to produce a new KRAZY KAT series. Amid a flurry of publicity, Bill Nolan set up the Krazy Kat Studio at his Long Branch, New Jersey house. Nolan and his wife Viola recently bought 540 Second Avenue from actor Charles Grapewin, who would later play Uncle Henry in The Wizard of Oz.

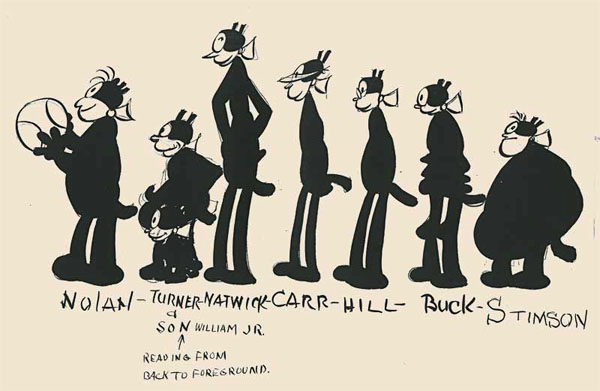

Bill Nolan’s father moved down from New York to work at the studio in some technical capacity. Nolan hired local artists George Hill and Robert Buck to assist with animation. Lyda Woolley taught physical education at the town’s high school before doing ink and paint for Nolan.

Bill Nolan’s father moved down from New York to work at the studio in some technical capacity. Nolan hired local artists George Hill and Robert Buck to assist with animation. Lyda Woolley taught physical education at the town’s high school before doing ink and paint for Nolan.

Theatrical cartoons were more sophisticated than when Nolan first worked on Krazy Kat a decade earlier, He needed some experienced animators. Nolan brought in Jack King from Bray Studios. Jack Carr quit Pat Sullivan’s place and headed to Long Branch. Bill Turner signed on. Turner began as an errand boy for Pat Sullivan beforelearning the trade in Bert Green’s studio. The biggest catch had to be Grim Natwick, returned from Europe with a sharpened skill set.

Natwick was back to painting covers for sheet music. Natwick actually moved into Nolan’s house as production geared up. Charles Mintz had a states-right deal for the Robertson-Cole Company to distribute 26 Krazy Kat cartoons through the season of 1925-1926. They were fast-paced, well-drawn, amusing toons. The lovelorn angle between Krazy and Ignatz was dispensed with. In Nolan’s version that cat and mouse were bitter enemies.

Krazy underwent a sex change from passive female willing to be victimized to a clever, bold, hard-charging male ready to meet any challenge. In effect he became Felix with a bow around his neck.

Things appear to have run smoothly for the first year.

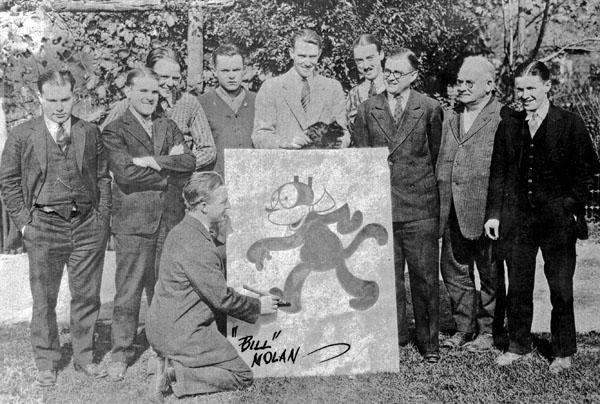

The “Krazy” crew in 1926

Bill Nolan’s Krazy Kat Studio was an amiable place to work. The caustic Charles Mintz stayed in Manhattan in his Candler Building office, engaged in a lawsuit with Pat Sullivan and a cross-country feud with Walt Disney. Nolan’s people socialized, enjoying the laid back atmosphere of their resort community.

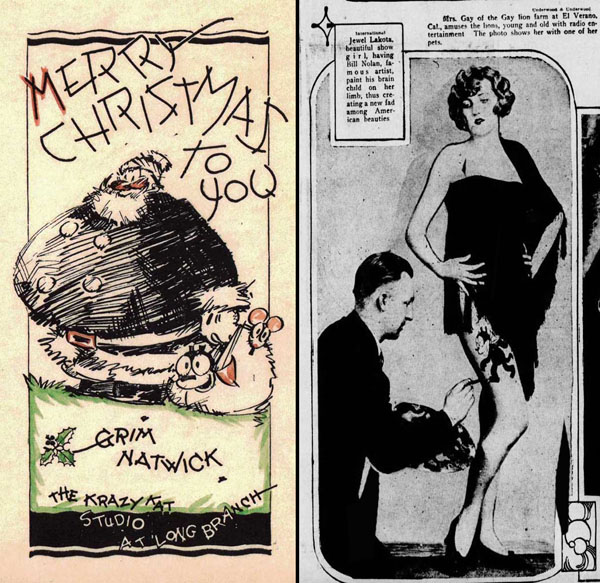

They formed a basketball team within in the local league. The KRAZY KATS didn’t win any championships, but they had fun, giving Grim Natwick a chance to vent his well-known competitive proclivities. Grim also spent his spare time rendering hand-drawn cards for friends and family.

Bill Nolan had it going on! He enjoyed a celebrity status in the New York art world.

Joseph P. Kennedy’s Film Booking Office absorbed The Robertson-Cole Company. Early in 1926 Bill Nolan flew to Hollywood to negotiate with the F.B.O.

A contract stating Winkler and Nolan would provide 52 animated cartoons to F.B.O. was signed. Half would be KRAZY KAT films, and the other half were unspecified. Nolan prepared to expans out of his little home studio, which now included the house next door.

A contract stating Winkler and Nolan would provide 52 animated cartoons to F.B.O. was signed. Half would be KRAZY KAT films, and the other half were unspecified. Nolan prepared to expans out of his little home studio, which now included the house next door.

Two-hundred acres were purchased in Lincroft, New Jersey for Nolan to build a better studio and a golf course. He was an avid golfer, often participating in tournaments sponsored by FILM DAILY Magazine. Then Charles Mintz dropped the other shoe.

KRAZY KAT was taken from Bill Nolan to be given to Ben Harrison and Manny Gould. Mintz breached his contract with F.B.O., bringing the Harrison-Gould cartoons to Paramount Pictures.

Plans to build in Lincroft were abandoned. Nolan honored his part of the F.B.O. contract by delivering 26 NEWSLAFFS cartoons. NEWSLAFFS used a new photographic process Nolan had just perfected. I’ve never seen one, so it’s impossible to say more. Mintz, Harrison, and Gould’s first

Krazy Kat was called NEWS REELING.

Most of Nolan’s staff went on to other studios, excepting Robert Buck who stayed local to play some baseball and work as a stereotyper at the Daily Record before joining the Army. Jack King went to Disney, where, as a director three of his cartoon were nominated for Oscars. King was the first director for Leon Schlesinger Productions, doing a series called BUDDY, before returning to Disney to put Donald Duck on the map.

Jack Carr went to New York, drawing Krazy Kat for Harrison and Gould. Carr then moved to Hollywood and did the voice for Jack King’s BUDDY cartoons. He later worked at M-G-M where he named Tom & Jerry.

George Hill also went to Hollywood and Leon Schlesinger Production after some time at Fleischer Studios in New York. Sam Stimson settled into Fleischer Studios as well, while Bill Turner was there heading the story department. Lyda Woolley joined Fleischer’s ink and paint crew. She made some impression on Doc Crandall, who compared her to Betty Boop. Lyda stayed behind when Fleischer moved to Miami, eventually taking a job with J.M Mathes’ prestigious advertising firm.

Right after the Long Brach studio’s demise Grim Natwick returned to freelancing in New York, keeping in touch with the old crew. Natwick later joined Fleischer Studios to create Betty Boop.

Bill Nolan received a call to Hollywood to be production manager and top animator at Walter Lantz’s studio on the Universal Pictures lot.

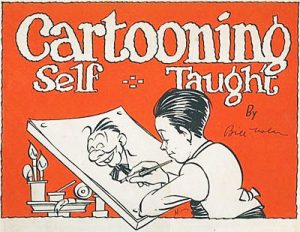

Jack Carr briefly worked with Nolan at lantz. Bill Nolan was the first voice of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit as sound came into movies. Nolan remained with Lantz until about 1935. The Chancery Court was threatening to foreclose on Nolan’s house in Long Branch because Charles Grapewin had mortgaged it to a bank before selling Bill and Viola the property. Nolan published a ‘HOW TO’ book on cartooning. He also turned out an indie cartoon titled FANNY FIDGET.

Frames from the rare print of Mayfair’s “Skippy” cartoon held at the Library of Congress

Nolan parted joined forces with Norman Stephenson, an ex-production manager at Disney. They were joined by ex-Disney animator Kenneth McLellan to form Mayfair Productions, with an office at 1558 North Vine Street. Mayfair worked at the United Artists studio lot out on Eagle Rock Boulevard to make Technicolor SKIPPY cartoons based on Percy Crosby’s newspaper strip. Percy Crosby got finicky, demanding artwork be redone. Creditors closed in on Mayfair Productions before any SKIPPY films were released.

Bill Nolan then worked for Charles Mintz again. Mintz had moved to Hollywood, doing KRAZY KAT and other cartoons for Columbia Pictures. Nolan animated one cartoon with Manny Gould under Ben Harrison’s direction, then moved on to Friz Freleng’s unit at M-G-M animating Captain and the Kids cartoons. Nolan soon went to Miami to work on Fleischer Studios’ Popeye – and feature film Gulliver’s Travels – reuniting with Grim Natwick there.

During World War Two Bill Nolan was in the Navy drawing technical manuals with people from Timm Aircraft. After the war Nolan did several films with John Sutherland (for his “Daffy Ditties” series).

Bill Williams, who’d worked for Timm Aircraft during the war, formed Williams-Nicolas Animated Productions with Nick Nicolas in 1949. They brought Nolan in. The firm did some work for Hollywood movies. Nolan became technical director on the series of FRANCIS THE TALKING MULE movies, about a talking mule, and the show, RHUBARB, about a cat which inherited a baseball team. Nolan was the person responsible for making Francis talk.

During 1954 Williams moved the company to Madison, Wisconsin. Nolan died December of that year.

Thanks to Devon Baxter for providing information and material that made this article possible.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

This article was a joy to read and the pictures were a joy (I had seen Nolan painting Krazy on a stripper’s leg before but couldn’t find it again). Anything on Nolan and the pictures he worked on is a must read, this included. Thank you, Bob and Devon, for such a good article!

I extend a tip of the Raymond Griffith top hat to Bob and Devon for this outstanding article and agree with Strumm that anything on Bill Nolan and the pictures he worked on is a must read. LOVE Nolan’s imaginative animation on the early talkie Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons produced by the Walter Lantz studio.

That’s a very interesting profile of Bill Nolan, an important yet little-known figure in cartoon history. I’m only familiar with his work on the Lantz cartoons, so this article fills in a lot of gaps for me. I’d love to have a look at that Mayfair Skippy cartoon someday.

I wonder if Long Branch, New Jersey, has done anything to acknowledge the city’s role in the early history of animation. Given the fat lot of nothing that Kansas City has done, probably not.

Many thanks for this article on an overlooked pioneer of animation. Nolan’s book “Cartooning Self-Taught” can be viewed at the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/Nolan.zip

Nolan’s greatest achievement might be the Oswald cartoons he directed for Walter Lantz between 1929 and 1931. They managed to bring the surrealism of silent cartoons into the sound era. Their idiosyncratic humor places them among the funniest cartoons of the early 30s.

You’ve really done amazing work here, not only summing up but expanding the available knowledge of Bill Nolan. It’s hard to overstate how large he loomed among early animators, yet today he’s lost so much ground vs. his then-equal Otto Messmer. Bill has mostly slipped off the map: apparently he always wore a simple gray sweatshirt to work at Universal and now it’s like a metaphor, vanished into gray. But his high notes sure were notable. 1] A big role in that later-era, more classic design of Felix and 2] a real innovator in terms of animating with foundational shapes; he was all ’bout those CIRCLES. What eventually was surreal, quirky, and outdated was AT FIRST a breakthrough in animated performance. Many thanks, Bob and Devon!