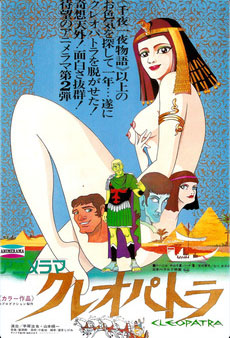

A year later, Mushi Productions’ second Animerama theatrical feature, Cleopatra, was released in Japan. Unlike A Thousand and One Nights, Cleopatra was a critical and commercial bomb. What went wrong? Everyone blamed an excessive self-indulgence by Mushi creator Osamu Tezuka, who apparently went completely gonzo.

A year later, Mushi Productions’ second Animerama theatrical feature, Cleopatra, was released in Japan. Unlike A Thousand and One Nights, Cleopatra was a critical and commercial bomb. What went wrong? Everyone blamed an excessive self-indulgence by Mushi creator Osamu Tezuka, who apparently went completely gonzo.

Audiences expecting something about Egypt’s Roman-era legendary femme fatale queen were met by a s-l-o-o-w 2001: A Space Odyssey space scene. After four minutes of opening credits (led off very prominently with Tezuka’s name), the story starts in a far-future city (the movie has been re-released titled Cleopatra 2525) with a pastiche of Cambria Productions’ notorious Synchro-Vox “living lips” – instead of live-action lips superimposed on a cartoon head and body, Cleopatra had cartoon faces superimposed on live-action bodies. Yes, the American Clutch Cargo was on Japanese TV (and the Japanese considered it just as grotesque as the Americans did), but even the few Japanese movie-goers who got the in-group joke considered it overly esoteric, for animation professionals only. Most audiences were just bewildered. (Dr. Tezuka himself told me about the deliberate Synchro-Vox joke, so this is not just a theory.)

The Technical Data: Cleopatra, 112 minutes; released on September 15, 1970; distributed by Nippon Herald. The idea and story were by Osamu Tezuka; the screenplay, under Tezuka’s supervision, by Shigemi Satoyoshi. The co-directors were Tezuka and Eichi Yamamoto. Character design was by Isao Kojima. Music by Isao Tomita.

The Cast:

The Plot: In the far future, a spaceship brings Mary (or Maria) back to Earth. Jiro and Harvey meet her, but are aghast when she is disintegrated. It wasn’t really Mary; it was a spy from the alien Pasateli who want to destroy all humans. The two friends find the real Mary and Chief Tarabahha (in some credits, Lt. Tarabach) waiting for them at a robot-served dinner. (The foursome are very racially integrated. Mary and Harvey are Caucasian, Jiro is Oriental, and Tarabahha is black.) During dinner, Tarabahha tells them that Earth has just learned that the Pasateli intend to conquer the humans with “the Cleopatra Plan”, but they don’t know what that is. Chief Tarabahha proposes to send the three’s minds into the past in a Time Machine, into the bodies of locals at Cleopatra’s court, to investigate. Harvey, who seems to consider himself a ladies’man, vows to “have some action” with Cleopatra.

After a surrealistic montage of time-traveling into the past, the scene stops at Caesar’s conquest of Egypt. (It should be noted that history in this movie flashes by so fact that the implication is that it all happens within months, though the actual period covered is seventeen years: 47 B.C. to 30 B.C.). This is the audience’s first glimpse of Tezuka’s taste for psychedelic slapstick humor and blatant anachronisms. Julius Caesar is depicted as a white-haired, olive-green-skinned 20th-century American political boss, smoking big, black cigars (which he later lights with a cigarette lighter) and riding in a 20th-century automobile-litter. The Roman conquest of Egypt is symbolized by scenes of comically exaggerated rapes, thousands of Egyptians being crushed by a gigantic press, and the Romans oppressing Egyptians who are copies of the more grotesque Japanese humorous manga characters of the late 1960s like Tensai Bakabon, Osomatsu-kun, and Dame Oyaji. This must have been enough by itself to guarantee no international sales of Cleopatra.

After a surrealistic montage of time-traveling into the past, the scene stops at Caesar’s conquest of Egypt. (It should be noted that history in this movie flashes by so fact that the implication is that it all happens within months, though the actual period covered is seventeen years: 47 B.C. to 30 B.C.). This is the audience’s first glimpse of Tezuka’s taste for psychedelic slapstick humor and blatant anachronisms. Julius Caesar is depicted as a white-haired, olive-green-skinned 20th-century American political boss, smoking big, black cigars (which he later lights with a cigarette lighter) and riding in a 20th-century automobile-litter. The Roman conquest of Egypt is symbolized by scenes of comically exaggerated rapes, thousands of Egyptians being crushed by a gigantic press, and the Romans oppressing Egyptians who are copies of the more grotesque Japanese humorous manga characters of the late 1960s like Tensai Bakabon, Osomatsu-kun, and Dame Oyaji. This must have been enough by itself to guarantee no international sales of Cleopatra.

The plot switches back from surrealism to humorous but coherent plausibility, and occasional real history. An emissary from Alexandria and his teenaged daughter present flowers to Caesar — Caesar takes the daughter instead. Young Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII (the real Ptolemy was fifteen years old), with his advisor, the eunuch Pothinus (the real power behind the historic Ptolemy’s throne), is terrified that Rome is going to annex Egypt, but he is reassured when Caesar says he is willing to rule from behind the scenes with Ptolemy as a figurehead. Caesar will keep the emissary’s daughter as a “translator”.

Meanwhile an Egyptian underground meets. They are violently opposed to Egypt’s surrender to the Romans, and are not much happier with Ptolemy’s Greek dynasty. (The native Egyptians are authentically notably darker-skinned than Ptolemy’s Greek dynasty. The movie is accurate in many little ways. Aside from the fantasy depiction of Caesar, Mark Anthony and Octavian look like their portraits on ancient Roman coins, allowing for the movie’s cartoony art style.) They want to assassinate Caesar, but are divided on how to get close to him. “Caesar is too tough to die.” “Then we will use a woman who will soften him up with sex.” Lydia, an attractive young virgin, volunteers for the job, but Apollodoria (clearly an older lesbian) claims that she must fail. “Caesar is a powerful man, so it will not easy for him to fall for any common woman. You should use a famous prostitute with much erotic skill.” “Where will we find someone like that?,” she is asked. “I already have.” Apollodoria’s candidate is Cleopatra, Ptolemy’s older sister. According to this movie, Ptolemy has ignored his sister, and she has mastered the erotic arts to gain some power, despite a very plain face. “I have no respect for my brother. I hate any man who yields to Caesar.”

Meanwhile an Egyptian underground meets. They are violently opposed to Egypt’s surrender to the Romans, and are not much happier with Ptolemy’s Greek dynasty. (The native Egyptians are authentically notably darker-skinned than Ptolemy’s Greek dynasty. The movie is accurate in many little ways. Aside from the fantasy depiction of Caesar, Mark Anthony and Octavian look like their portraits on ancient Roman coins, allowing for the movie’s cartoony art style.) They want to assassinate Caesar, but are divided on how to get close to him. “Caesar is too tough to die.” “Then we will use a woman who will soften him up with sex.” Lydia, an attractive young virgin, volunteers for the job, but Apollodoria (clearly an older lesbian) claims that she must fail. “Caesar is a powerful man, so it will not easy for him to fall for any common woman. You should use a famous prostitute with much erotic skill.” “Where will we find someone like that?,” she is asked. “I already have.” Apollodoria’s candidate is Cleopatra, Ptolemy’s older sister. According to this movie, Ptolemy has ignored his sister, and she has mastered the erotic arts to gain some power, despite a very plain face. “I have no respect for my brother. I hate any man who yields to Caesar.”

The Roman Army discovers and kills most of the conspirators. Apollodoria and Cleopatra escape in the confusion to an ancient Egyptian wizard living in a tomb with his pet leopard, Lupa. Apollodoria has already arranged with the wizard to transform Cleopatra into a super-sexy beauty that Caesar will be unable to resist. At this point two of the three future minds arrive in the past to take over local bodies. Mary becomes Lydia, who also escaped. Harvey becomes Lupa the leopard. This frustrates his chances of romancing Cleopatra, though he keeps trying – humorous bestiality.

The beautified Cleopatra captivates Caesar, to the point that he announces that he has made her the queen of Egypt so the Egyptians will keep a native ruler. He still plans to rule behind the throne. Ptolemy feels betrayed, and he and Pothinus openly fight Cleopatra’s Roman-supported puppet government. The Roman fleet is burned; in the movie Ionis, one of the Romans’ Greek slaves, escapes. His body is taken over by Jiro, the third future man, and he meets Lydia. They are captured by the Egyptians led by Ptolemy and Pothinus. Ionis kills Pothinus by using his future knowledge to make hand grenades, and Ptolemy drowns in the Nile during his retreat. (The latter is true.) This sequence features more of Tezuka’s crazy anachronisms; an audience prompter to stir up applause for Caesar, Ionis’ fight with an Egyptian warrior repeated in Slow Motion, and the hand grenades.

The Romans recapture Ionis, and Caesar, impressed by his fighting ability, makes him his personal slave for a gladiatorial fight in the Coliseum. To make sure that Ionis can win, Caesar gives him a gun. The anachronism is never explained.

Appolodoria reminds Cleopatra that she is supposed to be vamping Caesar to get close enough to assassinate him, and she slips him poison as they bathe together. Ironically, Caesar has one of his epileptic fits at this moment, and the poison brings him out of it. (Caesar did have occasional minor epileptic fits, but nothing as exaggerated as in this movie.) Cleopatra soon gives birth to Caesar’s son, Caesarion, and although she continues to give lip-service to Appolodoria’s orders to kill Caesar, her heart is not really in it.

Appolodoria reminds Cleopatra that she is supposed to be vamping Caesar to get close enough to assassinate him, and she slips him poison as they bathe together. Ironically, Caesar has one of his epileptic fits at this moment, and the poison brings him out of it. (Caesar did have occasional minor epileptic fits, but nothing as exaggerated as in this movie.) Cleopatra soon gives birth to Caesar’s son, Caesarion, and although she continues to give lip-service to Appolodoria’s orders to kill Caesar, her heart is not really in it.

Caesar makes his long-delayed triumphal return, bringing Cleopatra as an honored guest. Caesar’s wife, Calpurnia, is not happy. This sequence features one of Tezuka’s most extensive anachronisms, lasting for two minutes. The Roman triumph includes dancing girls. Tezuka begins by animating famous paintings of ballet and can-can dancers by Edgar Degas, going on to Renoir, Monet, and other 19th-century French Impressionists, and then seguing ever-faster into non-dancing works by Matisse, Modigliani, Delacroix, Botticelli, Leonardo, Van Gogh, Goya, Picasso, Mirò, Dali, David, Bosch, and others that could not be considered even vaguely appropriate, ending with Saul Steinberg. The sequence goes on to depict Caesar’s attempt to subvert the Roman Republic into giving him dictatorial power (Ionis’ stint as Caesar’s champion gladiator to win popularity), and powerful conservative Senators opposing him, leading to his famous assassination on March 15, 44 B.C. – presented as a Kabuki drama! Calpurnia tells Cleopatra that respectable Roman noblewomen will never recognize her or Caesarion.

After that, Cleopatra and Caesarion escape back to Egypt. The Roman government appoints Mark Anthony to follow and end Egypt’s independence. Anthony is well-meaning, but basically a comic-relief governor easily seduced by her. She “distracts” Anthony into continuing to allow Egypt’s independence for so long that Rome disowns him and replaces him with Caesar’s nephew, Octavian. Anthony commits suicide following Octavian’s victory at the Battle of Actium. Cleopatra, Ionis, and Lydia (and Lupa) retreat into the Great Pyramid, where Octavian kills Apollodoria. When Cleopatra attempts to seduce Octavian (later to become Caesar Augustus, the first Roman Emperor) in his turn, he turns out to be flamingly gay and impervious to her charms (but he is really turned on by the handsome Ionis). Cleopatra commits suicide by asp-bite and dies in delirium, calling out for Mark Anthony, clearly the one that she really loved.

Back in the future, the three give their report on the Cleopatra Plan, to seduce Earth’s leaders in the form of beautiful women and kill them all. The three’s discovery is just in time for Earth to strike before the final Pasateli kill order can be given.

Cleopatra is certainly interesting, but it was too avant-garde for either the critics or the movie-going public. By 1970, everything seemed to be souring economically; for Japan in general and for Mushi Productions in particular. Mushi had been in serious financial trouble since 1968, due partly to the stalling and slow shrinking of the overall Japanese economy, but it was certainly not helped by Tezuka’s obvious loss of interest in Mushi’s main specialty, children’s animation for TV, and his obsession with adult animation (Tezuka had always been interested in mature animation).

Cleopatra is certainly interesting, but it was too avant-garde for either the critics or the movie-going public. By 1970, everything seemed to be souring economically; for Japan in general and for Mushi Productions in particular. Mushi had been in serious financial trouble since 1968, due partly to the stalling and slow shrinking of the overall Japanese economy, but it was certainly not helped by Tezuka’s obvious loss of interest in Mushi’s main specialty, children’s animation for TV, and his obsession with adult animation (Tezuka had always been interested in mature animation).

During the 1960’s he had also personally produced such intellectual film-festival fodder as the half-hour Stories on a Street Corner (1962, before Mushi had produced anything commercial), and the 39-minute Pictures at an Exhibition (1966), plus five shorts of from three to eight minutes. But these were never expected to be commercially successful.) Mushi’s staff, due to Japanese formality, may not have been as openly confrontational as an American animation studio’s employees would have been, but Tezuka can have been in no doubt as to what the majority of his animators thought. After 1968-’69, Tezuka gambled Mushi’s future on his Animerama features. When Cleopatra brought only ridicule, Tezuka just walked away from Mushi Pro. He had already quietly started Tezuka Productions in 1968 to make his films his way without any arguments.

As said, Cleopatra was a failure. Big time. Tezuka sort-of disappeared (the public did not know about Tezuka Productions yet), and it was assumed that Tezuka had committed professional suicide. (Actually, Tezuka was concentrating on writing/drawing adult manga for other publishers. Tezuka Productions’ first animation, the 26-episode TV cartoon series Fushigi na Melmo (Marvelous Melmo), appeared from October 5, 1971 to March 26, 1972, but few TV viewers of children’s cartoons read the credits. In those days before anime fandom and before the VCR, it went unnoticed. Yet it showed Tezuka’s medical interest, and was an early work of Gundam creator Yoshiyuki Tomino. Apparently just another magical little witch series about an orphaned nine-year girl who, when she ate magical blue candy, transformed into a nineteen-year-old teenager to care for her little brothers, Tezuka emphasized – tastefully – the effects on a nine-year-old child suddenly hit by an older teenager’s hormones without growing slowly into them. Also, nine-year-old Melmo’s clothing did not change, usually leaving her in embarrassment and needing adult clothes fast! Wikipedia says, “Many Japanese parents reportedly hated the show since it raised many questions from children that parents were uncomfortable with answering.”) Mushi Productions stumbled publically and painfully on toward bankruptcy three years later. Yet as far as Tezuka was concerned, the worst was yet to come.In 1972, Mushi Pro, desperate to stave off bankruptcy, accepted an offer from a tiny American distributor, Xanadu Productions, to buy Cleopatra. Tezuka had always wanted to get American distribution, but not like this. Xanadu retitled the movie Cleopatra, Queen of Sex, and advertised it as a pornographic movie – the first hard-core animated pornographic feature. Knowing that Ralph Bakshi’s Fritz the Cat was about to come out with, it hoped, a X-rating, Xanadu advertised that its Cleopatra, Queen of Sex was the first animated movie to get an X-rating! – falsely, unless you consider that self-rating was technically legal in 1972. Xanadu never submitted Cleopatra to the Motion Picture Association of America for an official rating. But in fact, Fritz the Cat was released with its X-rating on April 12, 1972, and Cleopatra, Queen of Sex, dubbed into English, was not released until April 24, 1972. So Cleopatra, Queen of Sex was still not the first.

It bombed anyway. Audiences expecting lots of graphic sex and little else had a reaction like that of the viewer in Mel Brooks’ and Ernie Pintoff’s 1963 The Critic: “What the hell is this?” The reviews of Cleopatra, Queen of Sex as pornography were scathing, accusing it of deliberate false advertising. YouTube quotes one reviewer as saying that it was “kid stuff with naked breasts.” Tezuka scholars agree that if it had been submitted to the MPAA for an official rating, it would have gotten something milder than an X.

Cleopatra, Queen of Sex was the direct antithesis of Tezuka’s attempt to show that adult artistic eroticism could exist without degenerating into pornography. When Dr. Tezuka told me about this in 1979, he was still quivering in anger. When I told him that 1972 theater-goers had demanded their money back, he replied that he hoped that the American distributor had gone bankrupt!

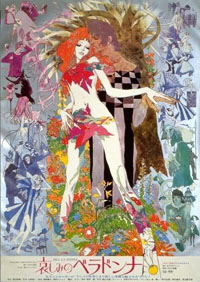

Belladonna of Sadness

Tezuka resumed the production of feature length animation with Tezuka Productions’ TV movies beginning with Bander Book in 1978, and theatrically with Phoenix 2772 in 1980, but they were children-friendly “family features”, not specifically for adults. Even Tezuka’s final international animation festival films like Jumping (6th Zagreb International Film Festival; June 11-15, 1984), Broken-Down Film (1st Hiroshima International Film Festival, August 18-23, 1985), and Legend of the Forest (10th Zagreb International Film Festival; May 30-June 3, 1988, less than a year before his death), had nothing in them that children could not see.

Next Week: The End of Mushi Pro.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

The credits of “Pictures at an Exhibition” spell Tezuka’s name phonetically as “Osam Tezka”. That is how his name was usually pronounced; the ‘u’ is silent. I thought that this was “in Japanese”, but I was told by someone from Osaka that it is really just in Tokyo dialect, although since Tokyo is the capital and the center of international business in Japan, the Tokyo residents are glad to have foreigners think that their dialect is the ‘proper’ accent for all Japan. Tezuka, who was from Osaka, did not mind the ‘u’ pronounced aloud although he was used to it being silent in Tokyo. Americans who really get into anime fandom will learn the nuances of Japanese stereotyped exaggerated regional humor. Anyone from Hiroshima is a really tough guy (see “Tenamoyna Voyagers” or “Handmaid Mai”) ; the Osakans are country bumpkins who love to eat squid (see “Azumanga Daioh” where a student from Osaka in Tokyo high school is nicknamed ‘Osaka’ and can’t convince anyone that she doesn’t really like squid more than any other snack food), and so on. Those outside Tokyo usually do not appreciate this. When A.D.Vision got the rights to “Abenobashi Shopping Arcade”, which is set in Osaka with the locals speaking in really thick Osakan accents, A,D.Vision dubbed it with really thick Texan/cowboy accents instead.

The statement about Japan’s general economic downturn around 1970 may need more explaining. From the 1950s to the mid-1960s, Japan’s recovery from the devastation of World War II was so rapid and dynamic that it was widely called “the Japanese economic miracle”, ending in “the Golden Sixties”. Japanese industry was able to churn out automobiles, TV sets, and other aspects of material prosperity, and the average Japanese family was able to afford them. Starting in the late 1960s, the rate of growth started to slow down. Salary raises became smaller and rarer. By 1970 the average family was harder-pressed to afford new goods. No one was hurting yet, but there was a cutback on luxuries such as going to the movies. Things got really bad with the international oil boycott of 1973, when the Arab-controlled Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) declared an embargo on oil exported to the U.S., and its ally Japan, for America’s support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War. This led to loooong lines at the gas pumps in the U.S., which got all of the publicity, but Japan was hurt, too.

Distribution companies in the U.S. were pretty notorious in attempting to come up with American equivalents of Japanese dialects in the 90s, usually resulting in ear-splitting Southern accents or cheesy “British”/upperclass accents. There’s nothing worst than an overdone accent that doesn’t sound natural, except maybe as camp value.

Convincing Southern accents seem to be very hard for voice actors to do. They tend to work better when the actor has a real dialect rather than a put-on, but anime dubbers are rarely that accommodating since they tend to spread their handful of VA’s talents thinly over multiple roles–often in the same series.

Oh wow, I didn’t know that Mushi Productions literally crumbled under the weight of its own artistic self-indulgence. I had never seen Cleopatra, but I had no idea it went THAT direction! I’m sure the general Japanese public that came to see this got a bitter sense of bait and switch once the sci-fi kicked in along with the self-conscious lampooning of the historical aspect. In a way, I think people really did want to see something along the lines of the Elizabeth Taylor or CB DeMille Cleopatra epics with more eroticism and skin–something they could at least partially take seriously as a steamy romantic.

On one hand it seems the films trying to make an artistic statement of the Cleopatra legend, but on the other it comes across like utter camp. It’s like it’s an animated version of Barbarella that’s desperately trying to be seriously considered and arthouse feature and going about it as obtusely as possible. I imagine that’s what drove the critics away from this one, normally the nucleus that would recognize greatness or artistic merit that would be generally lost to the public.

During the 70s a lot of feature producers went down this road trying to come up with the next avante-garde masterpiece that would be hailed as a truimph of the arts, but more often that not they just came across as turkeys and are generally remembered as commercial and critical bombs or at best niche cult classics.

As far as this feature is concerned, I’m curious if today has a better reputation among certain otaku who tend to clamor around Japanese animation that even has a whiff of artistic merit. That or the Tezuka diehards.

I don’t know about the Japanese press, but I understand that the only American reviews that it got in 1972 took the “Cleopatra, Queen of Sex” pornography publicity seriously, and since the movie never attempted to be pornography, it got very negative reviews as being either very ineptly made, or for deliberate false advertising — which was true in America. Nobody in America reviewed it as an avant-garde art film.

Now that 40+ years have passed, the cinematic community is judging as as closer to Tezuka’s original goal. From that view, the majority decision is that it is ancient history (rather than being about ancient history), is still too long, and is much too self-indulgent.

“I don’t know about the Japanese press, but I understand that the only American reviews that it got in 1972 took the “Cleopatra, Queen of Sex” pornography publicity seriously, and since the movie never attempted to be pornography, it got very negative reviews as being either very ineptly made, or for deliberate false advertising — which was true in America. Nobody in America reviewed it as an avant-garde art film.”

No doubt it just wasn’t going to work they way it did.

“Now that 40+ years have passed, the cinematic community is judging as as closer to Tezuka’s original goal. From that view, the majority decision is that it is ancient history (rather than being about ancient history), is still too long, and is much too self-indulgent.”

Pretty much the way I felt watching it the first time in the late 90’s.

Interesting. Tezuka must have influenced Bakshi and (Rene LaLoux) at some point. As for the film itself; entertaining in a completely unintentional way.

“Interesting. Tezuka must have influenced Bakshi and (Rene LaLoux) at some point.”

I do sorta wonder how much influence Tezuka even had over here at the time. We can still ask Bakshi about it I suppose but it’s hard to say how much influence either he or Laloux saw from Tezuka’s work. The 1970’s was a big time for certain artists to dabble in doing animated films with adult issues or content.

“As for the film itself; entertaining in a completely unintentional way.”

Wouldn’t surprise me.

That poster sure was misleading. I was expecting that film to more serious.

Sure isn’t when you even get a cameo of Astro Boy popping up at an unexpected moment.

“Belladonna of Sadness is essentially a slide show of still images based on the decadent late-Victorian art style of Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898). It was released in Japan on June 30, 1973 and only played for ten days.

It did have a kickin’ soundtrack by Masahiko Sato that somehow found it’s way to Italy via a vinyl LP released in 1975 (not sure if the film saw a release there but no such soundtrack recording was ever made of it back home besides one song on a 45rpm single).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIZdqIpuD94

http://i17.fastpic.ru/big/2011/0301/12/bdfbe026be5b2dcfdb4fc0aac669cd12.jpg

Jesus Christ this article has so many flaws and in Corrections 41 esoteric occult meaning in this work for one ionius declared he was Caesar’s Alchemist used his future knowledge of Soul transported back in time 2 then do magic him and Maria fall in love like they knew each other from a past life before they were born I’m not going to waste my time they met anything else watch the f****** movie

If you would like to know or see what real magic looks like in your universe then watch this movie. There had a lover you felt like somehow we’re soulmates that you knew them from a past life or before you were born other dimensions wave energy has contacted before you were formed in school. Form with all the elements that make up your mind. Strange to really think about what it is to be the about the nature The Human Experience and what really means to be alive and aware unconscious and have a soul.

Do you like to see ancient Roman magic in an ancient Greek Egyptian syncretic magic and its prime there were these special magus’ we just had power Knowledge from some way from within themselves the way of knowing they couldn’t explain they got this info because a part of them part of you is another dimension right now is in a higher dimension of some form. Hezekiah was messing with this esoteric idea being himself a magician / artist I mean he’s really did the servant of the one God the god that represents creativity life force energy creation matter movement kinetic energy Nazi have the inverse of this which could represent as vacuum selfishness self-serving. And although masculine and feminine plays out through gender roles these energies exist in the modern time do different in different levels throughout different genders and we shouldn’t you know judge anything from the past with a lens of the future