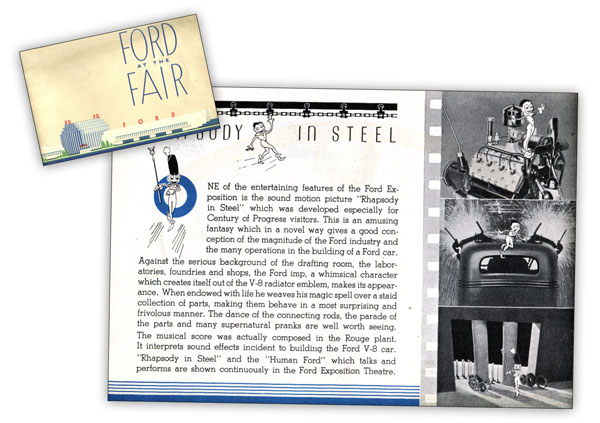

On May 26th, 1934 the 1933/34 Century of Progress Chicago World’s Fair opened for it’s second year. Amongst one of the additions for this second season was the Ford Motor Company’s Pavilion that showcased Henry Ford and his company’s contribution to the production of the automobile. One of the attractions in the pavilion was the ‘Little Ford Theater’ which screened an ambitious industrial film entitled Rhapsody In Steel that symphonically showcased Ford’s Rouge River plant and it’s assembly line process.

Frank Goldman

The exact production history of the Rhapsody In Steel is not currently known to the author and documentation (if any exists) is not available. Right now it can only be speculated by observing history pertaining to Audio Productions (aka Audio-Cinema) and the Ford Motor Company. Like many of Audio Productions’ industrial films, “Rhapsody In Steel” was not registered for copyright thus making the official release date somewhat of a mystery. However, as the 1933/34 Worlds Fair’s second season opened on May 26, 1934 it’s appropriate to assume that the film would have been first shown that day. Therefore production probably would have started in early 1934, if not earlier in 1933. Around the time Ford would have approached the studio, Audio Productions was just under five years old as it was established in 1929 by Frank Goldman selling his company Carpenter-Goldman Laboratories to Western Electric (a division of AT&T).

Early films produced by the studio consisted of internal industrial films for Western Electric and AT&T, externally sponsored motion pictures, educational films and also novelty films (such as the “Paul Terry Toons” Cartoons the studio produced). A number of these productions, such as the surviving 1932 industrial film “Man Against Microbe”, were highly received and gave the studio a respectable reputation. Looking at a few surviving Audio industrial films such as “Getting Together” (a 1933 cartoon where an animated character oversees the assembly of a telephone in stop-motion) and reading descriptions to the (lost as of 2018) “Musical Moods” symphonic travelogue series, one can imagine what Ford executives may have seen at theaters that attracted them to Audio Productions to sponsor a film that wasn’t the typical narrated documentary styled industrial film for their fair exhibit.

Early films produced by the studio consisted of internal industrial films for Western Electric and AT&T, externally sponsored motion pictures, educational films and also novelty films (such as the “Paul Terry Toons” Cartoons the studio produced). A number of these productions, such as the surviving 1932 industrial film “Man Against Microbe”, were highly received and gave the studio a respectable reputation. Looking at a few surviving Audio industrial films such as “Getting Together” (a 1933 cartoon where an animated character oversees the assembly of a telephone in stop-motion) and reading descriptions to the (lost as of 2018) “Musical Moods” symphonic travelogue series, one can imagine what Ford executives may have seen at theaters that attracted them to Audio Productions to sponsor a film that wasn’t the typical narrated documentary styled industrial film for their fair exhibit.

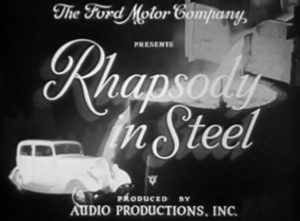

Rhapsody In Steel incorporated a number of characteristics from Audio’s earlier productions such as the “Musical Moods” series and Frank Goldman’s “Getting Together”, thus creating a unique film experience which beautifully put to use many of the studio’s talents. The film begins with a brief prologue of an automobile driving up to the camera and speaking to the audience. Unfortunately as of 2018 the prologue’s audio is missing, but judging by the superimposed footage of scenes from the Rouge River plant, one can speculate the automobiles’s dialogue having to deal with the concept of taking raw materials and transforming them into a Ford automobile through the assembly line process. Following the prologue, the opening title appears on screen, where Edwin E. Ludig’s musical score “The Rhapsody In Steel” begins and takes viewers on a triumphant, atmospheric saga showing the production of a Ford Sudan. The first half of the film uses beautiful cinematography by Leo Lipp and fancy editing techniques to highlight and pay tribute to the various assembly line workers.

Rhapsody In Steel incorporated a number of characteristics from Audio’s earlier productions such as the “Musical Moods” series and Frank Goldman’s “Getting Together”, thus creating a unique film experience which beautifully put to use many of the studio’s talents. The film begins with a brief prologue of an automobile driving up to the camera and speaking to the audience. Unfortunately as of 2018 the prologue’s audio is missing, but judging by the superimposed footage of scenes from the Rouge River plant, one can speculate the automobiles’s dialogue having to deal with the concept of taking raw materials and transforming them into a Ford automobile through the assembly line process. Following the prologue, the opening title appears on screen, where Edwin E. Ludig’s musical score “The Rhapsody In Steel” begins and takes viewers on a triumphant, atmospheric saga showing the production of a Ford Sudan. The first half of the film uses beautiful cinematography by Leo Lipp and fancy editing techniques to highlight and pay tribute to the various assembly line workers.

The second half of the film is animated and chronicles an animated cartoon character, the ‘V8 Imp’, overseeing a Ford Sudan assembling itself in stop motion animation; the stop motion is animated by Frank Goldman and is similar to the type of animation he would produce for Jam Handy following his departure from Audio Productions in 1935. The entire film features no narration and uses only Edwin Ludig’s triumphant score The Rhapsody In Steel to describe the images. Ludig, an overlooked but outstanding film composer, uses music inspired from Wagner, Beethoven, Rossini, Zamecnik theatrical cues, and even the sounds heard at the Ford Rouge River plant. According to the Ford Pavilion souvenir booklet and a review by Motion Picture Herald, Ludig spent several weeks in the Rouge River Plant composing the music score to give it an industrial sound reminisce of the factory.

The second half of the film is animated and chronicles an animated cartoon character, the ‘V8 Imp’, overseeing a Ford Sudan assembling itself in stop motion animation; the stop motion is animated by Frank Goldman and is similar to the type of animation he would produce for Jam Handy following his departure from Audio Productions in 1935. The entire film features no narration and uses only Edwin Ludig’s triumphant score The Rhapsody In Steel to describe the images. Ludig, an overlooked but outstanding film composer, uses music inspired from Wagner, Beethoven, Rossini, Zamecnik theatrical cues, and even the sounds heard at the Ford Rouge River plant. According to the Ford Pavilion souvenir booklet and a review by Motion Picture Herald, Ludig spent several weeks in the Rouge River Plant composing the music score to give it an industrial sound reminisce of the factory.

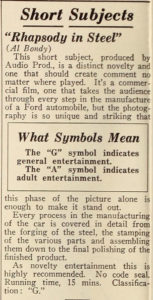

The film received raved reviews from the World’s Fair showings and was highly applauded when it went into theatrical and non-theatrical release domestically and internationally, following the fair. Motion Picture Herald credited the production as the fair’s most popular film, while Film Daily praised it in their June 22nd, 1934 issue as “THE BEST industrial Picture they had ever seen”. With the ending of the 1933/34 Worlds Fair Rhapsody In Steel was released theatrically by the Ford Motor Company and also Al Bondy Incorporated (a distributor of industrial films and B-movies through the states rights system); The Al Bondy release was edited down to 15 minutes and included an additional scene that depicts the animation sequence being dreamed by a Ford worker. Despite the changes, the film still continued to be well received as can be seen with Film Daily’s review that described the Bondy release as a “distinct novelty and one that should create comment no matter where played” and praised Leo Lipp’s “unique and striking” cinematography.

The film received raved reviews from the World’s Fair showings and was highly applauded when it went into theatrical and non-theatrical release domestically and internationally, following the fair. Motion Picture Herald credited the production as the fair’s most popular film, while Film Daily praised it in their June 22nd, 1934 issue as “THE BEST industrial Picture they had ever seen”. With the ending of the 1933/34 Worlds Fair Rhapsody In Steel was released theatrically by the Ford Motor Company and also Al Bondy Incorporated (a distributor of industrial films and B-movies through the states rights system); The Al Bondy release was edited down to 15 minutes and included an additional scene that depicts the animation sequence being dreamed by a Ford worker. Despite the changes, the film still continued to be well received as can be seen with Film Daily’s review that described the Bondy release as a “distinct novelty and one that should create comment no matter where played” and praised Leo Lipp’s “unique and striking” cinematography.

It’s not known when theatrical screenings of The Rhapsody In Steel ceased, however it may have been around the time of the 1939 World’s Fair as it was updated by Audio productions, in Technicolor, for the 1939 Ford Pavilion. (The remake was “Symphony In F” which attempted to outdo it’s superb 1934 predecessor; this will be discussed in a couple of weeks.) While theatrical exhibitions halted, non-theatrical releases continued for school use well into the Post-World War II era and was shown to shop classes and also to music classes (with a focus on Ludig’s score). Eventually, like many industrial/educational films, it was phased out and unintentionally obscured. Today as of 2018, it is unheard of to many professors, students, and historians of film history and filmmaking.

The Rhapsody In Steel, along with many other Ford films prior to the 1960s, was donated to the National Archives in 1963 where it’s original film elements still rest. The film is today fortunately in the public domain (it was never registered for copyright) which gives it an opportunity for a second life to inspire others with Frank Goldman’s documentary style. The author (who for the record does not care for Henry Ford for several reasons), has admired the film for how Frank Goldman took a potentially boring subject matter and symphonically portrayed it in an entertaining, high class manner. Below is the film which is sourced from a Beta transfer the National Archives did many years ago. Hopefully this article and viewing of the film will bring more attention to this iconic documentary sound film and lead to a 4K restoration of it…

The Rhapsody In Steel, along with many other Ford films prior to the 1960s, was donated to the National Archives in 1963 where it’s original film elements still rest. The film is today fortunately in the public domain (it was never registered for copyright) which gives it an opportunity for a second life to inspire others with Frank Goldman’s documentary style. The author (who for the record does not care for Henry Ford for several reasons), has admired the film for how Frank Goldman took a potentially boring subject matter and symphonically portrayed it in an entertaining, high class manner. Below is the film which is sourced from a Beta transfer the National Archives did many years ago. Hopefully this article and viewing of the film will bring more attention to this iconic documentary sound film and lead to a 4K restoration of it…

FILM LINK

In addition here is a video which shows the opening prologue, which as of 2018 is unfortunately missing its audio. (The author envisions the automobile’s voice sounding similar to the automobile in the 1953 educational film The Talking Car, and discussing the concept of converting raw materials into a Ford Sudan…):

A special thank you to Ray Pointer and Rick Prelinger for their research assistance.

Next Week: We’ll take a look at two films that were apparently Frank Goldman’s unofficial re-makes of “Rhapsody In Steel”… For Chevrolet!

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Fascinating stuff!

Anyone proficient in cartoon vehicle lip reading?

I know this article is from a few years ago, but as of spring 2020, you can find a very clean copy of Rhapsody in Steel from 1993 on YouTube from the Ford heritage channel.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R6ABlsLoTgg

“The Rhapsody in Steel” played in the State Theatre in Lennox, SD on Nov. 2, 1933. An ad for the movie was placed in our local newspaper, The Lennox Independent, by Gedstad Motor Company on Oct. 25, 1933.