An Introduction

What if I were to tell you that Once Upon A Time, that oddball animated cartoon on safe driving that looks like a Van Beuren Aesop’s Fable cartoon doped up on Technicolor steroids, is just as significant to animation and film history as Walt Disney’s Steamboat Willie, Flowers And Trees, or Three Little Pigs? Believe it or not this wild idea may not be too far fetched, thanks to research that’s been uncovered through the Media History Digital Library.

To be short, this tool has revealed that the cartoon was made in 1934, was able to use the three-strip Technicolor process at a time when Walt Disney had exclusive rights to it, and when released was reported to have been a highly respected and popular cartoon!

To be short, this tool has revealed that the cartoon was made in 1934, was able to use the three-strip Technicolor process at a time when Walt Disney had exclusive rights to it, and when released was reported to have been a highly respected and popular cartoon!

To briefly introduce those unfamiliar with Once Upon A Time, the film is a 1934 safe driving cartoon sponsored by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, produced by Audio Productions (a film studio that was a division of A.T.&T.), and was filmed in three-strip Technicolor. Trade ads credit Francis Lyle Goldman (a.k.a Frank Goldman) as it’s director, and Edwin E. Ludig as it’s music composer.

The cartoon’s ornate backgrounds were designed and drawn by Louis Jambor, while it’s unusually crude animation (which is not credited in any sources) is believe to have been done by Fleischer animators John Walworth and/or Hicks Lokey.

Below is a print of the film from the Library of Congress which beautifully shows off the film’s wild, but brilliant use of three-strip Technicolor:

To understand how an oddball safety film like Once Upon A Time was able to negotiate a special contract to use three-strip Technicolor and why it would have been highly praised upon it’s 1934 release, one needs to understand the era it was made. Driving during the 1930s was much different than it is today in 2019 as many traffic control systems/regulations were still in development. Two excellent examples of this slow progress are stop signs and traffic lights. The stop sign began appearing across the country in 1915, seven years after Henry Ford’s Model T’s began rolling around the country. The original style and size of these pre-mature stop signs were inconsistent and it wouldn’t be until 1922 that stop signs would be standardized nationwide, originally as a yellow octagon with black text; an action taken due to the number of accidents prompted by inconsistent signs. The now used red octagon white text signs replaced the yellow and black signs in 1954. Traffic lights, another important traffic regulation tool, were just as slow in development.

As indicated by an excellent 1937 Jam Handy short subject Seeing Green, traffic lights were unstandardized and inconsistent across the country. While efforts were ambitious to nationally standardize the now used green, yellow and red three light system, it was very slow due to a number of factors. Seeing Green (which was directed by Frank Goldman, who left Audio Productions in 1935 to go work for Jam Handy) can be viewed below:

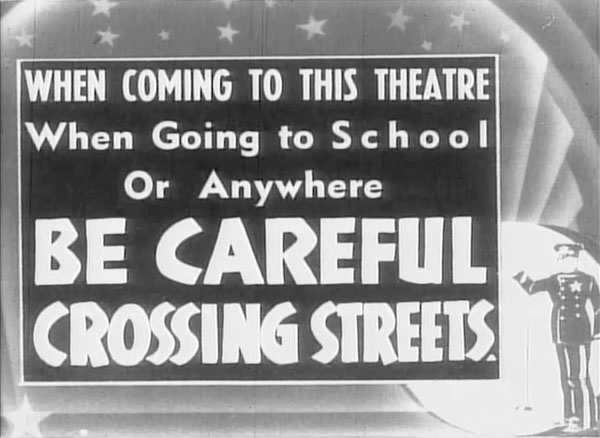

Due to the slow progress of safe driving signs and regulations, combined with the discourteous and careless acts of numerous motorists, many people were injured or killed from automobile accidents. As referenced in Once Upon A Time, thirty-three to thirty-four-thousand people were killed and over one million people were injured from automobile related accidents yearly during the early 1930s! To address this serious public safety epidemic, insurance companies and automobile manufactures came out with driving safety programs and aids to educate the public. Amongst these aids were motion pictures that were shown in theaters, school auditoriums, and to civic groups. These films, many of which appear to have been simple unsophisticated live action documentaries, were used frequently during the 1920s and into the 1930s.

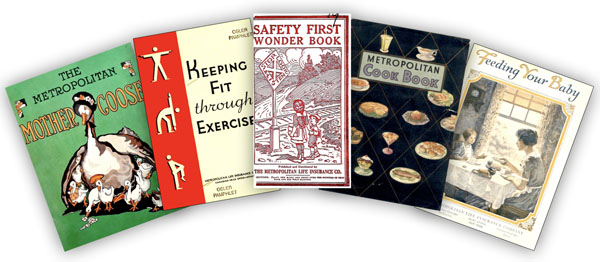

Various Metropolitan Life Insurance Company pamphlets and books covering a wide range of health, safety, and wellness topics.

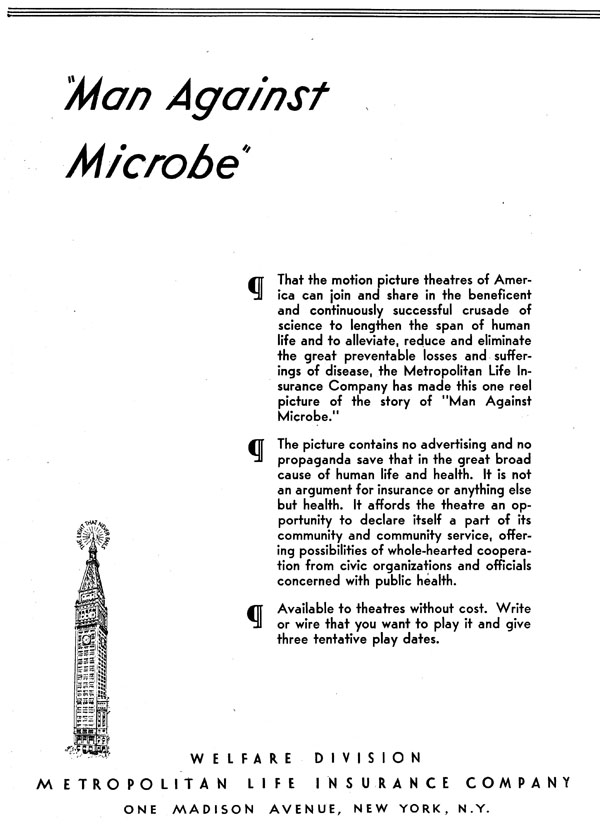

At some point in 1934 (possibly 1933) the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company took an interest in producing a traffic/drivers safety film that could be shown in movie theaters and also non-theatrically. Since it’s founding in 1868, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company invested in creating a variety of free public safety and health programs. These programs ranged from booklets, pamphlets, storybooks for children, etc., and by the 1920s had expanded into the form of motion pictures. By the 1930s, Metropolitan was collaborating with Audio-Cinema (who like Metropolitan was a New York City based company) to produce health and safety educational sound films. Unfortunately details regarding this relationship is lost to history at the moment, however it appears that Audio’s and Metropolitan’s first highly respected production was a 1932 common interest documentary called Man Against Microbe. The film was directed by Francis Lyle Goldman and was part of a large scale Dipatheria Immunization Campaign undertaken by Metropolitan, as well as encourage viewers to get vaccinated for the deadly disease as well as other viruses. As the film features Frank Goldman’s clever multimedia approach commonly seen in his Audio and Jam Handy films, it was highly praised by trade magazines who described it as interesting, clever, and highlighted it for not being a commercial.

The positive reception and outcome of the film prompted the two companies to work together again, only take on the public safety and health issue of the importance of safe driving. Who’s idea it was to make an animated Technicolor cartoon comedy to tackle the subject of discourteous and careless driving is a bit of a mystery (the author thinks that it was Frank Goldman from his masterful, showmanship driven educational films), but it was certainly brilliant and as indicated by trade magazines “the first of it’s kind”. From watching the finished Once Upon A Time cartoon it was certainly an experimental film that was influenced by the popularity and style of Walt Disney’s Technicolor Silly Symphony cartoons, most specifically Three Little Pigs.

It’s worth noting that Once Upon A Time is extremely similar to Three Little Pigs, as both are nursery rhyme styled Technicolor musical comedies that drive an important moral. (For Three Little Pigs its the importance of hard work and taking pride in it, while Once Upon A Time is safe, careful and courteous driving.) Both films revolve around a highly catchy theme song that were both, as indicated by trade ads, the most popular asset to both productions. In addition both films make clever use of Technicolor to enhance their storytelling.

It’s worth noting that Once Upon A Time is extremely similar to Three Little Pigs, as both are nursery rhyme styled Technicolor musical comedies that drive an important moral. (For Three Little Pigs its the importance of hard work and taking pride in it, while Once Upon A Time is safe, careful and courteous driving.) Both films revolve around a highly catchy theme song that were both, as indicated by trade ads, the most popular asset to both productions. In addition both films make clever use of Technicolor to enhance their storytelling.

Three Little Pigs was released in May of 1933 and would be awarded an Academy Award for best animated short film of 1933, in March of 1934. The popularity of the cartoon and its song Who’s Afraid Of The Big Bad Wolf took flight around the same time Metropolitan and Audio-Cinema/Productions would have begun pursuing the Once Upon A Time project. The immense popularity of the Three Little Pigs, and other nursery rhyme musical Technicolor Silly Symphony’s such as Old King Cole certainly inspired Audio and Metropolitan to make a Silly Symphony styled educational film in three-strip Technicolor. Due to the seriousness of affectively preaching safe driving, Audio and Metropolitan saw the importance of using the three-strip Technicolor process for their cartoon. The use of the process would certainly have the audience’s attention, but it was also the only color system that could accurately reproduce color’s affiliated with traffic signs, lights, etc.,: Green, Yellow/Amber, and Red.

Two scenes from Once Upon A Time: On the left is the stop sign as it appeared from 1922 up to 1954, a yellow octagon with black text. And on the right the three color traffic light system that was slowly being standardized and installed across the country. Its worth noting that in 1934 three-strip Technicolor was the only film color process that could accurately produce Red, Green, and yellow, colors associated with safe driving.

At the time Metropolitan and Audio wanted to take on this good Samaritan project, three-strip Technicolor for animated films was locked into an exclusive deal with Walt Disney. Despite this bump in the road, Metropolitan saw several important needs to use the process and apparently were able to negotiate a special, strict agreement with Technicolor (and possibly Disney) to use the process. What details and clauses were in this agreement are unfortunately unknown as no documentation is currently available. Despite this absence of information there are some hints hidden in plain site in the Once Upon A Time cartoon and also in a brief article that Film Daily ran in October of 1934, both of which hint of what these might have been.

NEXT WEEK: In Part 2 we’ll explore what these clauses may have been…

A still from a 1930s era safety theater snipe alerting children to look both ways when crossing the street.

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

My biological father died of a car accident when I was 5 while driving fast in a Ford pickup truck or Jeep in black ice, so these accidents are no joke and this film hits right at home. Had I been a been a simiilar accident that happened before he had to replace the truck a week before the fatal, I wouldn’t be here writing this comment.

And while the film didn’t mention drunk driving, car injuries like the ones on the film killed Princess Diana a couple years before my father,

Car accidents are no joke.

It might be that a technicality was found in Disney’s “exclusivity” to the use of the Three Color Technicolor Process as Disney’s use was for theatrical films, where industrial films were a different category and were distributed in a different manner. This becomes a fine point since some of the Jam Handy industrials had an amount of theatrical booking. So the application for the types of films might be the detail worth examining.

Excellent post. I love reading about the genesis of things that are now commonplace in the U.S. Looking forward to Part 2.

I believe John Walworth was probably an inbetweener or assistant animator on this cartoon. He was about 20 years old at the time of the making of this film.

The production of Once Upon A Time’s fits within the time frame of when Hicks Lokey was at Audio, where he went after being fired from Van Beuren because of union activity and when he went to work for Fleischer. The Cinderella segment has echoes of Fleischer’s Poor Cinderella (or is it vice versa?).