Thomas Edison’s often oppressive thumbprint is evident in the earliest days of animation. Edison’s company released the trick films made by James Stuart Blackton, who directed the live-action prologue for Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo film. Back in 1911 Nemo was the sum of American hand-drawn animation. Then McCay’s nemesis John Bray made a dreamlike romp about a sausage guzzling dachshund. Pathe, distributors of Bray’s subsequent cartoons, were partnered with Edison in a patent trust. Blackton handled release of McCay’s second animated film in 1912 about a thirsty mosquito.

Thomas Edison’s often oppressive thumbprint is evident in the earliest days of animation. Edison’s company released the trick films made by James Stuart Blackton, who directed the live-action prologue for Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo film. Back in 1911 Nemo was the sum of American hand-drawn animation. Then McCay’s nemesis John Bray made a dreamlike romp about a sausage guzzling dachshund. Pathe, distributors of Bray’s subsequent cartoons, were partnered with Edison in a patent trust. Blackton handled release of McCay’s second animated film in 1912 about a thirsty mosquito.

By 1913 that mosquito had infected artists across the Hudson River. John Bray ran a studio at his Highland Falls farmhouse. Edison’s arch rival Carl Laemmle and his Universal Motion Picture Manufacturing Company got into the act with Éclair Studios in Fort Lee, New Jersey by backing THE NEWLYWEDS cartoon series, based on a comic-strip by George McManus. Universal also had Hy Meyer doing animation for their newsreels from his apartment overlooking Central Park. Out on Long Island, Gaumont used animation in their newsreels. Lyman H. Howe’s Travel Festival Company of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania had Vincent Whitman animating minute long screen ads called photoplaylets to show between movies.

Raoul Barre

Barre’s little shop prospered. He subcontracted some work from Bray Studios. It didn’t take Raoul Barré long to outgrow 2826 Decatur Avenue, though that building’s place in animation history was far from over. Edison installed Willis O’Brien there from 1916 to 1917 to make a few stop-motion shorts.

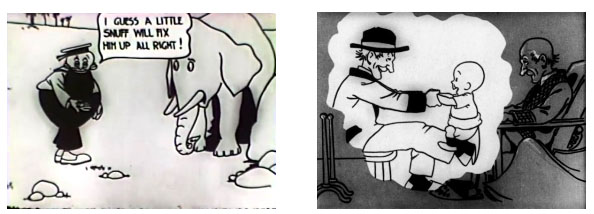

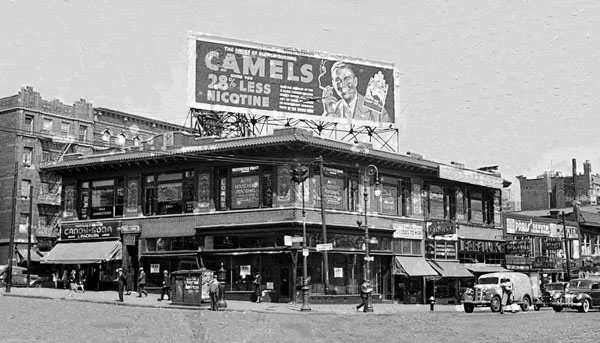

By that point Raoul Barré had moved six blocks away into the newly built Fordham Arcade Building at 387 East Fordham Road. A wave of artists were trying their hand at that new animation thing. Frank Moser, Gregory La Cava, George “Vernon” Stallings, and Pat Sullivan trekked up there to the Fordham section of the Bronx to learn under Barré and Nolan. They made the ANIMATED GROUCH CHASERS series for Edison to release.

Barré brought in popular newspaper cartoonist Rube Goldberg to write THE BOOB WEEKLY series. George Stallings animated them, and Pathe released them in 1916 with great fanfare. That flow was disrupted when newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst opened International Film Service in Manhattan. Bill Nolan and most of Barré’s crew deserted him for fatter paychecks from Hearst, leaving Barré to figure out how to keep the doors open there in the Fordham Arcade Building. The answer to that dilemma came in the form of one Charles Bowers.

Grouch Chasers (left), Cartoons On Tour (right)

Charles Bowers

A replacement crew needed to be assembled and trained for this revised Barré-Bowers Animation Studio. Over time that roster included future luminaries such as Dick Huemer, Burt Gillett, Mannie Davis, Manny Gould, Ben Harrison, and Ted Sears. A pugnacious fellow named Dick Friel supervised and animated. Frank Nankerville, noted newspaper cartoonist in those days, worked there as well, and his daughter Edith was with the camera department.

Izzy Klein went to work there in July of 1918 after being laid off when Hearst’s International Film Service suddenly shut down. Klein later recalled taking the Third Avenue elevated train north to its last stop at Fordham Road, near 190th Street. The Arcade Building straddled Webster and Decatur avenues, connecting the two streets with a hallway along the rear. Klein entered from 2555 Webster Ave. The studio, on the second floor, was all bare wood floor, with green paint dimming sunlight through large windows. Charles Bowers kept an office there, while Bud Fisher ran the business end of the company from 1600 Broadway in Manhattan. Klein never met Raoul Barré, who’d gotten in the habit of avoiding Charles Bowers. Soon after Klein arrived someone informed Barré that Bowers was swindling him. Barré caught Bowers outside the studio and threatened to shoot him. The police released Barré after psychological observation and he never returned to what became the Charles Bowers Studio.

Fordham Arcade Building

Bowers’ team couldn’t turn out MUTT & JEFF cartoons fast enough to fill exhibitors’ demand. Money was being made hand-over-fist. Then Dick Friel informed Bud Fisher that Charles Bowers was swindling him. Bowers was out, Friel got put in charge, and production carried on. There are a whole lot of factors deserving their own column about the intricacies of Bud Fisher’s legal and financial trepidations. Suffice it to say that Charles Bowers finagled his way back in and set up a second MUTT & JEFF production studio in Mount Vernon, the town just above the Bronx. Cartoons from both studios were photographed in the Arcade Building and negatives made at Edison’s Decatur Avenue lab.

The Mount Vernon branch had Izzy Klein, Leighton Budd, Carl Meyer, Louis Glackens, and F. M. Follett animating, with Ted Sears lettering title cards. In the Bronx, Dick Friel relied heavily on Burt Gillett, Mannie Davis, Manny Gould, and Ben Harrison. During 1921 Friel left to animate for the Lee-Bradford Corporation at 701 Seventh Avenue in Manhattan. Burt Gillett took charge of Bud Fisher’s Bronx operation.

In his typically impetuous manner Charles Bowers abandoned Mount Vernon, moving that studio back to the Bronx, roughly a mile above the Fordham Arcade Building. Bowers rented a two story building. Actually the second story was a half floor with a big roof patio covering the rest. Bud Fisher closed the Fordham Arcade studio, allowing Bowers to cram animators from both shops into the tiny second floor while Bowers experimented with stop-motion puppets on the first. Bowers’ constant shenanigans got him fired again and Gillett was back in charge.

By 1925 Bowers was back, this time with a studio on Long Island. Gillett was there under Bowers control until Gillett led a coup and formed Associated Animators. But animation in the Bronx still had one last Hurrah. 2826 Decatur Avenue was an annex of Long Island’s Audio-Cinema Productions in 1929. Audio-Cinema went into partnership with Paul Terry and Frank Moser to make a series of “Terry-Toons” with sound. Terry-Toons were animated at the Decatur Avenue facility and sound work was done in Long Island City.

By 1925 Bowers was back, this time with a studio on Long Island. Gillett was there under Bowers control until Gillett led a coup and formed Associated Animators. But animation in the Bronx still had one last Hurrah. 2826 Decatur Avenue was an annex of Long Island’s Audio-Cinema Productions in 1929. Audio-Cinema went into partnership with Paul Terry and Frank Moser to make a series of “Terry-Toons” with sound. Terry-Toons were animated at the Decatur Avenue facility and sound work was done in Long Island City.

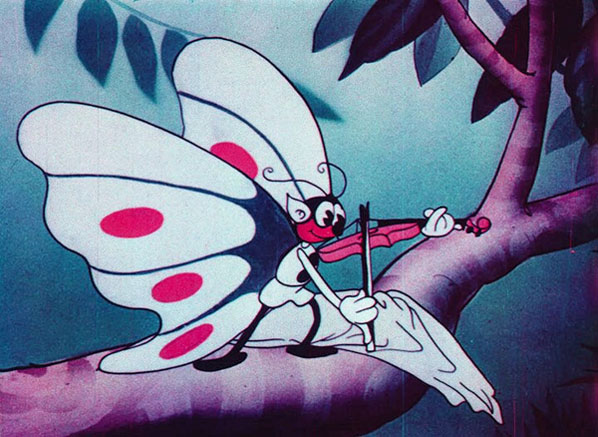

Western Electric, parent company of Audio-Cinema, had Frank Moser direct THE FAMILY ALBUM, a companion piece to Max Fleischer’s FINDING HIS VOICE. Paul Terry and Moser animated the film. Terry and Moser’s small crew included animator Cy Young and inker/painter Lillian Friedman. They also worked with Frank Goldman on photoplalets for Flit insecticide and Lysol cleaner, which were designed by Ted Geisel. Goldman used the facility to make theatrical cartoon advertisements for Aetna Life Insurance. A real gem came out of the Decatur Avenue lab in 1932 when Fairmount Pictures released MENDELSSOHN’S SPRING SONG.

The Brewster Color Film Corporation of 58 First Street in Newark, N. J. financed this wonderful curiosity to demonstrate their product. Montrose Newman, business manager of Audio-Cinema’s animation department, seems to have supervised the project. The cartoon’s designer Herman Roessle, an engineer born in Germany, broke the story down for Cy Young to animate. Inbetweening, inking, and painting was all done by Lillian Friedman.

left to right: Herman Roessle, Cy Young and Lillian Friedman

MENDELSSOHN’S SPRING SONG is a worthy note on which to conclude this Bronx tale. Herman Roessle rode its success into the position of animation supervisor for Audio-Cinema. The film caught Walt Disney’s eye, landing Cy Young the job of founding Disney’S special effects department. Lillian Friedman went on to Fleischer Studios to be recognized as the industry’s first female animator.

Raoul Barré spent some time at Pat Sullivan Productions working on Felix the Cat cartoons before moving back to his native Canada. Charles bowers became Charley Bowers, a manic whirlwind refashioning himself as the star of his own silent comedies. Animation in the Bronx dwindled down to a few bits here-and-there by Audio-Cinema, but the borough played an important part in those early days.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

Thanks for the information on “Mendelssohn’s Spring Song”, a one-of-a-kind early sound cartoon. I only wish Brewster Color had made more cartoons in the “Jingles” series. I especially like the close-up of the butterfly’s violin where one of his fingers disarticulates itself from his left hand and moves along the string on its own. Carlo Peroni, the musical director on that cartoon, was the principal conductor of the San Carlo Opera Company, which had an opera house in New York but spent eight months of each year on the road. He conducted the first sound film of a complete opera, Leoncavallo’s “I Pagliacci”, in 1929.

Great NYC synopsis!

Another fantastic post Bob! As the youngest writer here at Cartoon Research, you’re research here is truly inspiring!

The credits on the surviving color print of Spring Song say “Picturized by Herman Roessle in Brewster Color”, while the B&W dupe that circulates oddly has alternate credits that say “Photographed by…”—so I’ve accordingly always thought that Roessle served (at least primarily) as the cameraman. I’d like to know the source(s) for the information that he was the designer and “broke down the story” on this cartoon.

And for a lot of the other information for that matter. Lots of great information and writing here that may very well all be right on the mark, but in typical animation historian fashion, lacking citations of where the information originated—this came from an interview with an animator (which are great but not infallible sources), that came from this historical documentation, etc.—that let the rest of us see that the information is indeed reliable. I’d like to think of Cartoon Research as a more solid resource for history about animation and its artists, and spare my grains of salt for more deserving uses. Nothing personal, Mr. Coar, because again, your work here is by no means sub-par, and I’m glad to see more information getting put out there about this particular corner of animation history especially; it’d just be nice if a rise above the status quo could come with it.

Fantastic work Bob!