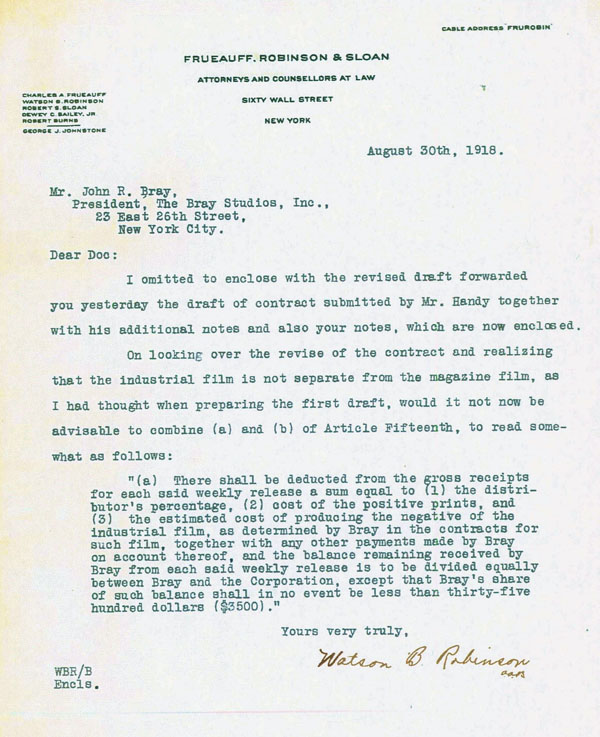

Five years after Pathe started distributing COLONEL HEEZA LIAR cartoons Bray Studios was expanding beyond animation. The summer of 1918 had U.S. troops fighting Across Europe while Bray turned out military training films. Corporate contracts for industrial films proved to be another source of income. Bray had his associate Watson B. Robinson draw up a contract with Jamison Handy’s Newspaper Films Corporation in Chicago with an eye to picking up clients in the Midwest.

Five years after Pathe started distributing COLONEL HEEZA LIAR cartoons Bray Studios was expanding beyond animation. The summer of 1918 had U.S. troops fighting Across Europe while Bray turned out military training films. Corporate contracts for industrial films proved to be another source of income. Bray had his associate Watson B. Robinson draw up a contract with Jamison Handy’s Newspaper Films Corporation in Chicago with an eye to picking up clients in the Midwest.

Robinson refers to Bray as “Doc” in that correspondence, indicating a deep friendship between the two. While Freuesff & Robinson tended to Bray Studios’ corporate structure, patent attorney Clair W. Fairbank litigated the growing number of Bray-Hurd Trust lawsuits.

Bray pushed his territory farther west, dropping Pathe, essentially a New York operation, for Paramount Pictures in Hollywood. Big time movie producer Sam Goldwyn formed a partnership with Bray, increasing the studio’s capitalization from ten thousand dollars to a million-and-a-half dollars. Jacob Leventhal was a vice president in the new corporation, and also on the board of directors along with Max Fleischer and Watson B. Robinson.

Newspaper baron William Hearst had suspended his International Film Service cartoons during the war. Now, Hearst paid Bray to take them over. A lot of Hearst’s old animators were called back, including Bill Nolan, Frank Moser and Grim Natwick. The IFS team did HAPPY HOOLIGAN, KRAZY KAT; and JERRY ON THE JOB.

Grim Natwick directed the JUDGE RUMMY series. Milt Gross contributed his writing/directing talents to several IFS toons produced by Bray. Mixed Into this creative whirlpool was young artist Walter Lantz, at age nineteen already a veteran of IFS and Bowers’ MUTT AND JEFF crew. David Hand returned east from Chicago to get a job with Bray Studios working on Fleischer’s OUT OF THE INKWELL films.

The Bray-Goldwyn Studio launched with some thrust. During 1920 an attempt at a color cartoon was among the eighty-five animated shorts they released. Then it began to crumble. Part of the problem was Margaret Bray’s tightfisted management. Artists didn’t get all the supplies they needed and were told to make do. At the same time, Margaret invested in the couple’s fancy new Norwich, Connecticut house, set in an elite neighborhood.

Social appearances needed to be maintained. There must have been talk, gossip, about the boy Paul, tucked away out of sight in military school. Paul came over from Germany bearing Margaret’s maiden name, fueling speculation he was born to her out of wedlock. None of this would have mattered to the men in the studio, unless it caused Margaret to over-exert her authority out of embarrassment. Max Fleischer and Jacob Leventhal left in 1921 to open their own studio. Only eighteen cartoons came out of Bray Studios that year.

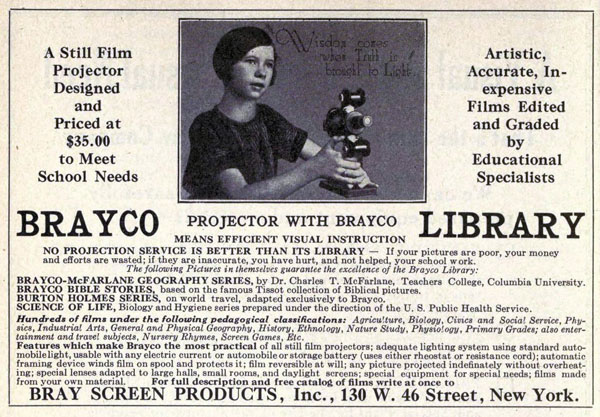

Difficulties ensued with the Newspaper Films Corporation. Jamison Handy ignored most of Bray’s instructions. Handy went rogue on several issues, didn’t bring in any customers, wasted capital on projects Bray found unnecessary, and held up matters with constant bickering over stock options. Bray fired Handy. John and Margaret began marketing prints of their cartoons and educational films through Bray Screen Products, Incorporated from an office at 120 West 42nd Street, with a sales catalogue listing the movies available, mostly cartoons. This functioned as Brayco, a whole other entity from Bray-Goldwyn, which was in trouble. Morale was low. The Brays split from Goldwyn, and regrouped.

During 1922 Bray Productions bought out the Realart Exchange, occupying that space at 130 West 46th Street for offices and an educational films exchange. Seventeen year old Bill Sturm came over from New Jersey to join the animation department. Sturm had started out part time with Pat Sullivan Productions while still in high school. Now he divided his time between Bray and attending the Art Students League on West 57th Street.

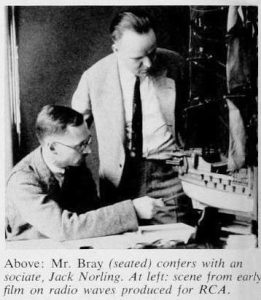

Bray discontinued the IFS deal with Hearst and most of those animators moved on. Wallace Carlson departed, returning to his old gig in Chicago. Frank Goldman oversaw Bray’s educational TECHNICAL ROMANCES series. Then Goldman was gone to start his own studio in 1923. Bray found himself reliant on John Norling, who’d trained under Fleischer and Leventhal. 1n 1923 John Norling started a studio right there in the Neptune Building. His partner Arthur Loucks had been an assistant advertising manager at Burroughs Adding Machine Company, one of Bray’s clients. Loucks & Norling were often subcontracted by Bray Studios.

Bray discontinued the IFS deal with Hearst and most of those animators moved on. Wallace Carlson departed, returning to his old gig in Chicago. Frank Goldman oversaw Bray’s educational TECHNICAL ROMANCES series. Then Goldman was gone to start his own studio in 1923. Bray found himself reliant on John Norling, who’d trained under Fleischer and Leventhal. 1n 1923 John Norling started a studio right there in the Neptune Building. His partner Arthur Loucks had been an assistant advertising manager at Burroughs Adding Machine Company, one of Bray’s clients. Loucks & Norling were often subcontracted by Bray Studios.

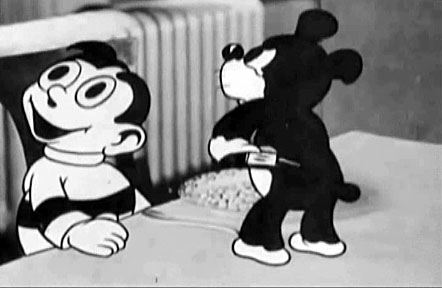

George “Vernon” Stallings, veteran of the Barré Studio, was promoted to supervisor of animation. George Stallings used the name “Vernon” to avoid confusion with his famous baseball manager father. The elder George Stallings was called ‘the Miracle Man’ due to his leading the last place Boston Braves to a 1914 World Series victory. Walter Lantz and David Hand worked under Stallings’ supervision. COLONEL HEEZA LIAR got a makeover, taking a page from OUT OF THE INKWELL, mixing a live-action George Stalling with the cartoon Colonel. These were cheaper to make than fully animated cartoons, and pretty weird to-boot.

Famous Players-Lasky’s animation department seems to have gone bust. Earl Hurd reopened Earl Hurd Cartoons in Kew Gardens. Hurd’s son Earl Junior was cameraman and studio manager. BOBBY BUMPS were released through Educational Film Exchange.

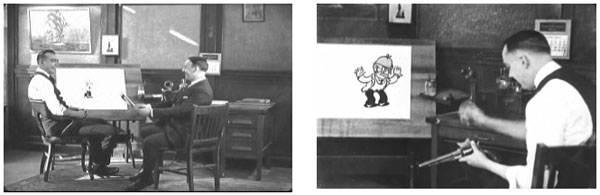

COLONEL HEEZA LIAR had run its course by 1924. George Stallings left because of health issues, so Walter Lantz took over supervising Bray’s cartoons. Lantz knew his job depended on devising a hit character. He created DINKY DOODLE.

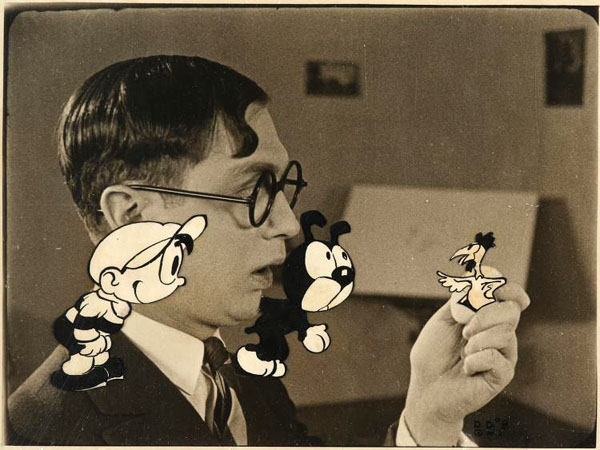

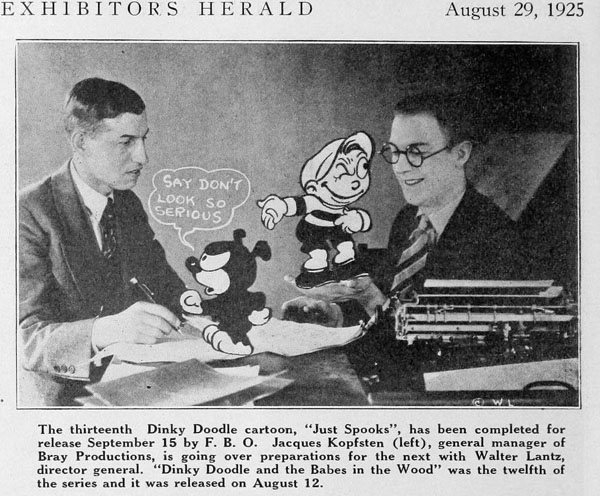

Lantz appeared in each film, interacting with the animated boy Dinky Doodle. Sometimes bits of stop-motion were used, anything for a laugh. That type of combo film could be marketed as either a cartoon or a comedy short.

John and Margaret spent more and more time in Hollywood on business trips. They met with Joseph Kennedy, a Boston-based politician who jumped on the motion picture bandwagon early as a producer and distributor. Bray signed a deal for Kennedy’s Film Booking Office of America to distribute his cartoons.

In 1924 Bray Screen Products opened at the 46th Street locale so Brayco could market a projector that showed film strips. Not moving pictures, but strips with pictures. Simple and affordable.

The Bray enterprise now spread out across multiple Manhattan locations. Dealings with Kennedy soured and distribution switched to Standard Cinema. Jaques Kopfstein, highly respected member of the Advertising Engineers Society and vice president of Chadwick Pictures, was picked to represent Bray Productions in some west coast sales negotiations.

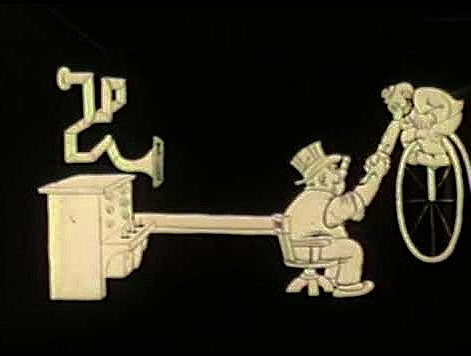

Earl Hurd’s studio had Ben Harrison there for thirteen PEN AND INK VAUDEVILLE cartoons released by Educational. They were uninspired white forms against a black background meant to kill time between acts at vaudeville shows.

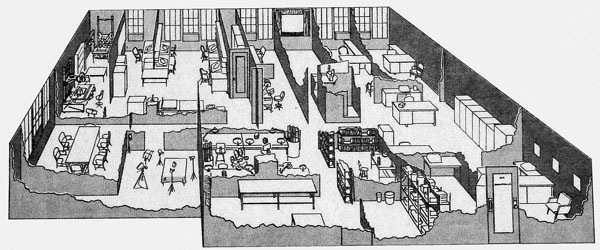

Bray Studios abandoned the Neptune Building in 1925, taking more space at 130 West 46th Street for animation and other departments. Walter Lantz came up with an UNNATURAL HISTORY series and PETE THE PUP. Lantz appeared on-screen in both. David Hand co-directed some with Lantz, and animated while Lantz looked after other details. Live-action sequences were shot at Tec-Art Studios on West 44th Street.

Bill Sturm had moved on to Max Fleischer’s shop. Walter Lantz was twenty-four and running an animation studio. David Hand was about the same age. Italian-born Clyde Geronimi, not much younger, joined them. If Clyde Geronimi wasn’t busy assising Lantz on a film, he was concocting some practical joke to play on a co-worker. Geronimi’s favorite target was David Hand because Hand got the most upset. Those high jinks seemed less disturbing to Chinese-American animator Cy Young who always focused intensely on his drawing.

Walter Lantz’s younger brother Michael was then in art school studying sculpture. Mike Lantz had a friend named Jimmie (Shamus) Culhane who could draw. Walter Lantz got the sixteen year old Culhane a starting position at Bray as an office-boy. Jimmie Culhane’s main job was to punch holes in pages so they would line up on animators’ pegs. Jimmie also ran errands, carefully avoiding the stern glare of Margaret Bray as she made her inspection rounds.

Walter Lantz’s younger brother Michael was then in art school studying sculpture. Mike Lantz had a friend named Jimmie (Shamus) Culhane who could draw. Walter Lantz got the sixteen year old Culhane a starting position at Bray as an office-boy. Jimmie Culhane’s main job was to punch holes in pages so they would line up on animators’ pegs. Jimmie also ran errands, carefully avoiding the stern glare of Margaret Bray as she made her inspection rounds.

Culhane’s natural talent soon led him to inking cels. The kid was fast and accurate. At age six Jimmie had witnessed Winsor McCay on stage performing the GERTIE act, and animation seemed to be in his blood. Lantz, who’d been twelve when he saw the GERTIE film, understood and took Culhane under his wing. That training paid off when one day a Bray animator got too drunk to draw and Culhane filled in for him. Earl Hurd returned to Bray’s animation wing.

New York DAILY GRAPHIC sports cartoonist Ving Fuller had joined Lantz’s team. John McCrory put in some time with the camera department, as did photographer Ansel Adams. Jacques Kopfstein, now general manager, interacted closely with Lantz. Kopfstein personally wrote promotional articles for DINKY DOODLE and the UNNATURAL HISTORY films.

John Bray’s interest in cartoons waned. He and Margaret were busy schmoozing in Hollywood. They finally adopted that boy, legitimizing him as Paul A. Bray at age twenty-six. Paul married, moved into the house next door in Norwich, settling into the vice presidency of Bray Studios.

John Bray’s interest in cartoons waned. He and Margaret were busy schmoozing in Hollywood. They finally adopted that boy, legitimizing him as Paul A. Bray at age twenty-six. Paul married, moved into the house next door in Norwich, settling into the vice presidency of Bray Studios.

Jacques Kopfstein started his own company in early 1926. John McCrory had moved on as well, running a little animation studio half a block west of Bray’s shop on 46th Street. 1927 turned out to be the end of Bray Studio’s days as a serious animation studio when the entertainment division was disbanded. Walter Lantz went on to greater fame with Woody Woodpecker, while David Hand, Jimmie Culhane, Cy Young, and Clyde Geronimi all became important members of the Disney organization.

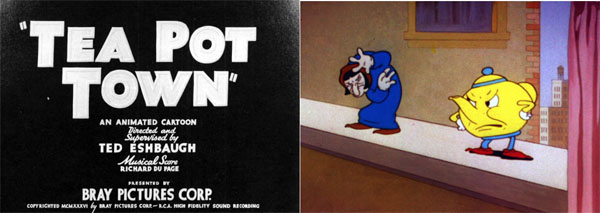

When Lipton Tea engaged Bray Studios to make the theatrical cartoon short TEA POT TOWN in 1936 Bray farmed production out to Ted Eshbaugh.

Over time Bray reorganized a smaller animation department to enhance educational and industrial films. By the mid-1940s that department would be run by Elaine Kaduson, a former fashion advertising illustrator for Gimbels Department Store. Kaduson was trained in industrial arts, costume design, illustration, and advanced technical drafting by the New York school system. She worked on military films during the war and was supposedly a free-lance animation artist for Disney Studios.

Sterling Television Company bought broadcast rights to a bunch of Bray cartoons in 1952, including: ten OUT OF THE INKWELL; twenty BOBBY BUMPS; twelve DINKY DOODLE; and eleven UNNATURAL HISTORY films. Max Fleischer returned to Bray Studios to revive the animation wing, without much luck. Bray Studios operated out of the Godfrey Building at 729 Seventh Avenue, while John Bray Productions kept offices at 122 West 55th Street.

Sterling Television Company bought broadcast rights to a bunch of Bray cartoons in 1952, including: ten OUT OF THE INKWELL; twenty BOBBY BUMPS; twelve DINKY DOODLE; and eleven UNNATURAL HISTORY films. Max Fleischer returned to Bray Studios to revive the animation wing, without much luck. Bray Studios operated out of the Godfrey Building at 729 Seventh Avenue, while John Bray Productions kept offices at 122 West 55th Street.

A mystery surrounds Fleischer’s production supervisor William G. Gilmartin. Early on, Fleischer Studios had someone in that job named William A. Gilmartin. Were they relatives? William G’s Queens address from 1940 is not reflected in that year’s census records. He’s just ghosting me.

Anyways, after Max Fleischer and William G. Gilmartin were gone in 1963 Rodell Johnson was director of animation for Bray. Rod Johnson did watercolors at Disney for the first five feature films. The Army commissioned him Captain to supervise animation at the Signal Corps’ Astoria facility. Post war, Johnson became director of animation for Shamus Culhane Productions, with a stop at Bill Sturm Studios before going to Bray.

Howard Beckerman recalls Rod Johnson commenting on how poorly equipped Bray’s animation department was.

1969 found Bray Studios relocated to the Film Center Building at 630 Ninth Avenue. John Bray held the title Chairman of the Board. Paul assumed the role of President. His son Paul Jr. was Vice-President. Margaret had been ill for a while and passed away the year before. Paul Jr. was a pilot, and the studio offered aerial photography. Military contracts with the Air Force, Marine Corps, and U.S. Navy continued. Rod Johnson remained Director of Animation, offering both wide-screen and standard productions.

Having lived nearly a full century, John Randolph Bray passed away in 1978, as Bruce Wands replaced Rod Johnson. Bray Studios’ art department only had four people by then. Bruce Wands left in 1980 to make a name for himself in the blossoming field of computer animation.

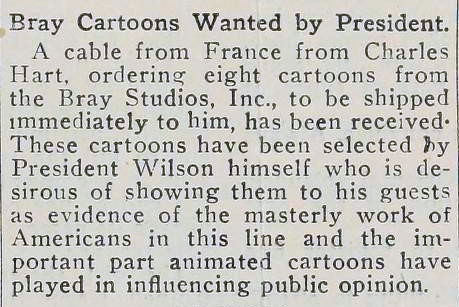

Paul Jr. inherited the presidency of Bray Studios, moving it closer to home at 19 Ketchun Street, near the Saugatuck River in Westport, Connecticut. The last listing I’ve seen there was for 1999. Paul Jr. was killed in a 2003 plane crash. Bray Studios seems a particularly Twentieth Century enterprise, bursting onto the scene as a powerhouse, only to be surpassed by the industry it helped to forge. Largely forgotten now, Bray Studios’ importance might best be reflected in this news article from December 1918 as President Woodrow Wilson convened the Versailles Conference to repair war ravaged Europe:

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

This is a very interesting account. I had no idea the Bray studio lasted so long and went through so many permutations. I’ve always associated it with the silent era.

I suppose it’s possible that Paul Bray was born to Margaret out of wedlock. It strains credulity to consider that she would have emigrated to America with her sister and left an infant son behind, but stranger things have happened. However, in Part 1 you wrote that Paul was born in Elberfeld, which is a very long way from Margaret’s hometown of Frankfurt-an-der-Oder; they’re on opposite sides of Germany. It’s also possible that Paul was an orphaned relative, which, in those days of lower life expectancies, happened all too often. Orphaned children from bourgeois families would get shunted from aunt to uncle to cousin until they found a satisfactory arrangement; and boys who proved a handful were often sent, as Paul was, off to military school. (A similar situation occurred with Ludwig van Beethoven’s nephew Carl, who was unhappily in the composer’s custody for a short time.) Since by 1910 Margaret was married, childless, successful, and very far away, the family might have felt that sending the boy off to her was the ideal solution. And Paul, finding himself living in a big house in Connecticut with a glamorous couple who made animated cartoons, no doubt would have made any accommodations necessary to avoid being sent back to the military academy in Germany. But this, too, is speculation, and at this late date it’s doubtful that we’ll ever get to the bottom of it.

Hi Paul, I’m Lisa. Margaret was my great grandmother’s sister. I have some family gossip! How are you connected to this story? I’d love to get info from you too. Get in touch if you like..

Lisa

Lisa,

Hello. I recently purchased an Original 1925 Brayco Film Projector in the original case. It still works. I was thinking that maybe you would be interested in purchasing it for your family history. You can contact me at my office at 585-448-0133.

Have a great day,

Jeff

Westside Traders Emporium

Rochester, NY 14624

Good article Coar! Odd that you still neglect to mention the Bray Animation Project, as without it many of this research, images (HEEZA LIAR, DETECTIVE is only available in the first Cartoon Roots set) and understanding wouldn’t be anywhere as possible http://brayanimation.weebly.com/

Also, the PEN AND INK VAUDEVILLE cartoons were produced by Earl Hurd on his own for Educational, and weren’t at all a Bray product. Ben Harrison did indeed work on them (as Devon Baxter highlights in his Ben Harrison anecdotes article, https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/the-annotated-handwritten-notes-of-ben-harrison/), but he give accurate information on the studio behind them and distributor

I didn’t know Lantz had a younger brother that worked briefly in animation. Wonder why Micheal didn’t work at his elder brother’s animation studio.

I don’t believe Michael Lantz worked at Bray. He became a world famous sculptor.

It sure is a lot of fun reading your articles on early New York animation, Bob. Are you going to go in to the business history of Felix the Cat and Pat Sullivan studios? When did Jacques Kopfstein take over the reins of the Sullivan enterprise? Did he run it into the early sound era? I’ve seen his credits on some sound Felix cartoons.

I know of Jacques Kopfstein primarily as the producer of Les Elton’s magnum opus “Monkey Doodle”. According to an article by Charlie Judkins, Elton worked at Bray Studios in 1916-17. I hope you’ll devote some attention to Kopfstein, Elton and “Monkey Doodle” at some point in this series of posts on New York’s animation history.

I’m attempting to lay groundwork for context right now. Then i want to get into a lot of the lesser-known general service studios – and there are a lot of them.

Don’t know much more about Kopfstein.

In an interview Mike Barrier conducted with Gerry Geronimi, Stallings was fired by Bray because he had a habit for being late. Though Geronimi didn’t say it, drinking might have been a factor of Stallings’ excessive tardiness.

I’ve read he left “due to illness”. Alcoholism is a disease.