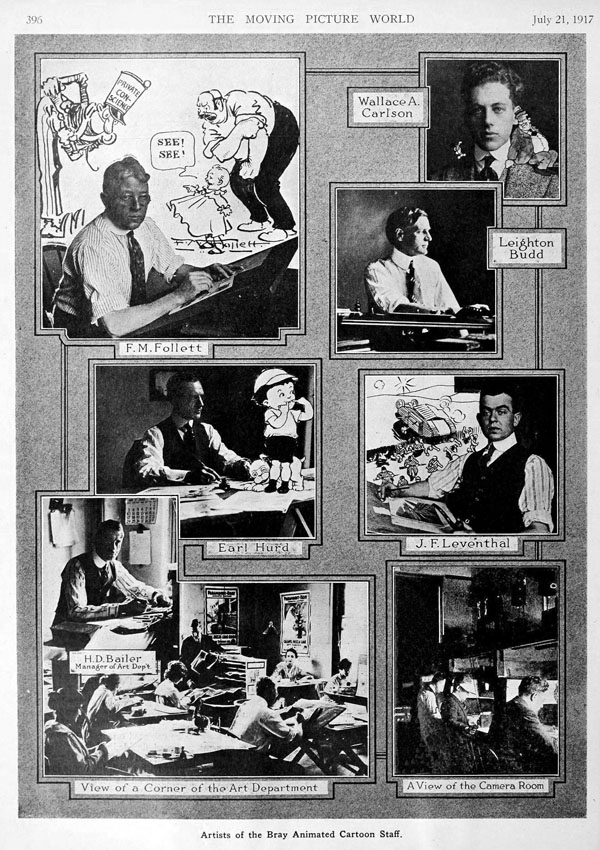

MOVING PICTURE WORLD presented the above glimpse of Bray Studios in July 1917. BUSINESS SCREEN Magazine gave its take on a page in April 1961. That was in observance of Bray Studios’ fiftieth anniversary, being a couple years premature. Bray Studios, as a producer of films, did not come into existence until 1913, that year which kicked off the animation industry in this good old U.S. of A.

John Randolph Bray had no problem playing fast and loose with the facts about his business. As best as I can gather, he was born 1979 in Addison, Michigan. Modern America was just arising as Thomas Edison introduced incandescent lighting and the Transcontinental Railroad linked both coasts. Folks in Addison, a farming village of less than three hundred people, learned about such events from the newspaper, perhaps alongside an announcement that traveling Methodist Presbyterian minister Edward Bray and his wife Sarah had a son. John was educated at the Detroit School for Boys. Displaying strong drawing skills, he also attended the Detroit School of Art.

John Randolph Bray had no problem playing fast and loose with the facts about his business. As best as I can gather, he was born 1979 in Addison, Michigan. Modern America was just arising as Thomas Edison introduced incandescent lighting and the Transcontinental Railroad linked both coasts. Folks in Addison, a farming village of less than three hundred people, learned about such events from the newspaper, perhaps alongside an announcement that traveling Methodist Presbyterian minister Edward Bray and his wife Sarah had a son. John was educated at the Detroit School for Boys. Displaying strong drawing skills, he also attended the Detroit School of Art.

1896 found John Randolph Bray enrolled in Michigan’s Alma College to study civil engineering. His heart wasn’t in it and after a year Bray dropped out to pursue a journalism career in Detroit. He landed a position as a reporter for the Detroit Evening News in 1901. It proved unglamorous, but opened the door for a job in New York as a cartoonist at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle a couple years later. Working there, Bray became friends with fellow artist Max Fleischer.

While living in Brooklyn J. R. Bray met Margaret Till, who had recently migrated from Germany to the U.S. with her sister Johanna. The Till sisters hailed from the city of Frankfurt, along the Oder River, an area which would become the Polish border after a couple of World Wars. It’s unclear how John and Margaret were acquainted.

Her sister Johanna was an artist, so possibly through that. However they met, John Bray and Margaret Till were soon on their way to the altar. The wedding took place on August 25, 1904 in Detroit with John’s father officiating. Margaret had her sister Johanna there. John’s best man was Edward F. Thieler, a Brooklyn business man starting up an advertising company specializing in store and window displays. John and Margaret then settled into a Brooklyn apartment at 240 Warren Street, the Cobble Hill neighborhood. Johanna lived with them, as did a Till brother named Fritz, then clerk.

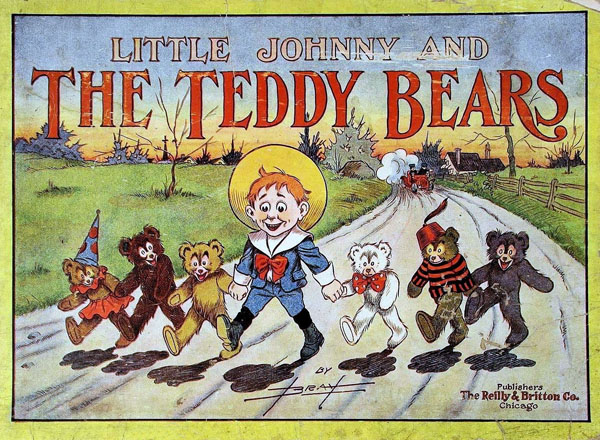

John prospered at the Daily Eagle, making connections. When his friend Max Fleischer got married, Bray was able to help the man find a better job as a technical illustrator at the Electro-Light Engraving Company on Pearl Street. Johanna Till wed John’s pal Edward Thieler in 1906, setting up house in Brooklyn. Bray kept drawing. A store window display, maybe one of Thieler’s, got Bray thinking about Teddy Bears, leading to a highly successful comic strip in JUDGE Magazine.

John prospered at the Daily Eagle, making connections. When his friend Max Fleischer got married, Bray was able to help the man find a better job as a technical illustrator at the Electro-Light Engraving Company on Pearl Street. Johanna Till wed John’s pal Edward Thieler in 1906, setting up house in Brooklyn. Bray kept drawing. A store window display, maybe one of Thieler’s, got Bray thinking about Teddy Bears, leading to a highly successful comic strip in JUDGE Magazine.

LITTLE JOHNNY AND THE TEDDY BEARS caught on big. J. R. Bray’s name spread. Cartoon strips only existed for a few years and didn’t have many creative stars yet. Winsor McCay made a splash at the New York Herald with his LITTLE NEMO IN SLUMBERLAND strip. McCay’s friend George McManus, over at the New York World, penned THE NEWLYWEDS. Out in San Francisco this guy Bud Fisher produced MUTT AND JEFF, which Hearst newspapers had syndicated into a nationwide craze. Membership in that elite club brought in serious money.

John and Margaret bought a farm on Vineyard Avenue in Highland, New York, more than seventy-five miles north of Brooklyn. Situated just west of the Hudson River, their eighty acre property contained fruit orchards, three houses, a barn, and several small out- buildings. They dubbed the place “Braybourne”, moving in with their German cook Bertha and her infant son. John’s parents were invited to stay. He wearied of the Teddy Bear strip. This new century promised to be something unprecedented, an era filled with untapped possibilities. John Randolph Bray intended to tap those possibilities.

Margaret agreed to earn their way while John freelanced and tinkered with projects. He experimented with stop-motion animation, having no real luck. Word circulated about Winsor McCay making a motion picture with moving drawings of his Little Nemo characters. It seemed to be a time-consuming process, taking years. When McCay’s film was released in 1911 it made money. So did the simpler mosquito film McCay released in 1912. By that point John Bray was already at work on THE ARTIST’S DREAM.

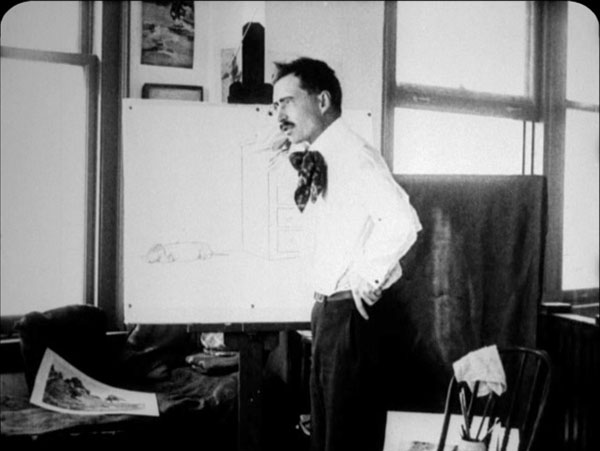

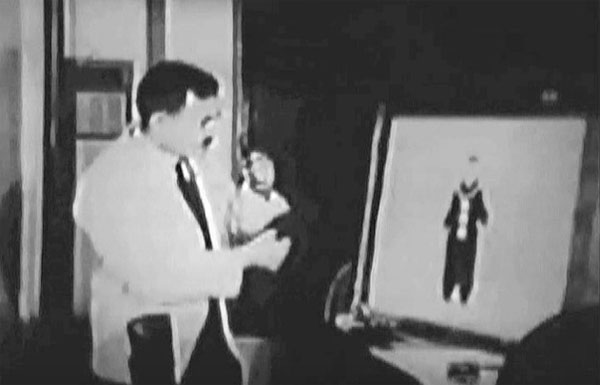

J. R. Bray plays artist Charley Heckler in the short film. Heckler completes a large drawing of a dachshund sleeping next to a dresser. Atop that dresser is a plate of sausage. When Heckler turns his back the dog climbs up and steals the sausage. Heckler, perplexed, draws another sausage in its place. That’s the basic idea. But it turns out the artist has been asleep, dreaming the whole time, only to be awakened when his wife Margaret scolds him. Newspaper cartoonist Raoul Barré was hired to work on the animation.

Now the question arises as to what occupation engaged Margaret in her role as breadwinner. Family lore states she was a translator for Columbia University. Only, Columbia says there is no record of this. Events down the road indicate some connection between Margaret Bray and Columbia University. The more immediate mystery at this point concerns the origin of Paul Albrecht Till. Born during 1900 at Elberfeld, Germany, Paul’s parentage is uncertain. He migrated to New York City at the age of ten.

Now the question arises as to what occupation engaged Margaret in her role as breadwinner. Family lore states she was a translator for Columbia University. Only, Columbia says there is no record of this. Events down the road indicate some connection between Margaret Bray and Columbia University. The more immediate mystery at this point concerns the origin of Paul Albrecht Till. Born during 1900 at Elberfeld, Germany, Paul’s parentage is uncertain. He migrated to New York City at the age of ten.

We’ll come back around to all that. As for 1913, John and Margaret had a saleable film. It contained a cute cartoon dog and a couple good laughs. Pathe agreed to distribute it.

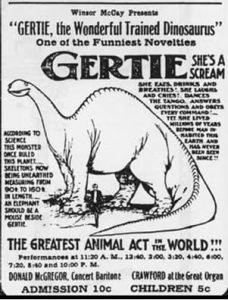

Better yet, Pathe would buy an animated cartoon every month for a six month period. The Brays had backed the right horse. By 1913 several movie studios tested the waters with animated drawings. The Éclair Moving Picture Company in Fort Lee, New Jersey was doing a series based on George McManus’s THE NEWLYWEDS strip. The Selig Polyscope Company in Chicago produced Sidney Smith’s OLD DOC YAK. Winsor McCay was doing a film at his home in Brooklyn about a trained dinosaur named Gertie. John Bray pretended to be a reporter writing a story and got McCay to reveal his whole process. Bray then used that information to set up the world’s first production studio dedicated exclusively to animated films.

Better yet, Pathe would buy an animated cartoon every month for a six month period. The Brays had backed the right horse. By 1913 several movie studios tested the waters with animated drawings. The Éclair Moving Picture Company in Fort Lee, New Jersey was doing a series based on George McManus’s THE NEWLYWEDS strip. The Selig Polyscope Company in Chicago produced Sidney Smith’s OLD DOC YAK. Winsor McCay was doing a film at his home in Brooklyn about a trained dinosaur named Gertie. John Bray pretended to be a reporter writing a story and got McCay to reveal his whole process. Bray then used that information to set up the world’s first production studio dedicated exclusively to animated films.

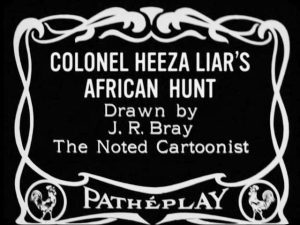

It was decided to feature an ongoing subject. Rather than license an existing character, Bray created Colonel Heeza Liar. This boisterous pipsqueak spun tall tales depicting himself in fantastic situations. The studio was set up on the Braybourne farm in Highland.

CORRECTION: The photo of the house (above) reported to be from John and Margaret Bray’s farm in Highland, New York is actually their house at a later property in Connecticut. The NY property does not appear to have been called Braybourne. That was also the CT property. On a related note, Highland, NY only recently became aware of the historical significance of the Brays’ presence there. Hopefully more will surface.

Margaret read Henry Ford’s book on assembly line production. Earl Hurd, a newspaper illustrator from Kansas City who’d dabbled in animation, was brought in. Harry Bailey, an artist from New Mexico, proved valuable organizing the camera department.

The artists commuted to Highland from New York City every Monday, either by boat up the Hudson River, or taking the Metro North train to Poughkeepsie, then crossing the railroad bridge there on a trolley. Each Friday they went home. A film per month proved difficult, so Bray filled out the commitment with a couple cartoons Raoul Barré and Bill Nolan made at the Edison Lab in the Bronx. Colonel Heeza Liar caught on and Pathe ordered more.

The artists commuted to Highland from New York City every Monday, either by boat up the Hudson River, or taking the Metro North train to Poughkeepsie, then crossing the railroad bridge there on a trolley. Each Friday they went home. A film per month proved difficult, so Bray filled out the commitment with a couple cartoons Raoul Barré and Bill Nolan made at the Edison Lab in the Bronx. Colonel Heeza Liar caught on and Pathe ordered more.

Paramount Pictures wanted a series as well. The Brays moved their whole operation to Manhattan near the end of 1914, leasing space in the Neptune Building at 23 East 26th Street, over-looking Madison Square Park. Some of the financing may have come from Watson. B. Robinson, a powerful Wall Street attorney. I haven’t been able to nail down the exact connection between Bray and Robinson, but there are a couple possibilities. Both men were born the same year in Michigan, 120 miles apart. They may have attended the same school in Detroit. Both men attended Alma College, so they

Paramount Pictures wanted a series as well. The Brays moved their whole operation to Manhattan near the end of 1914, leasing space in the Neptune Building at 23 East 26th Street, over-looking Madison Square Park. Some of the financing may have come from Watson. B. Robinson, a powerful Wall Street attorney. I haven’t been able to nail down the exact connection between Bray and Robinson, but there are a couple possibilities. Both men were born the same year in Michigan, 120 miles apart. They may have attended the same school in Detroit. Both men attended Alma College, so they

could have met there.

John Bray and Watson Robinson don’t seem to have much in common. Robinson was athletic, captain of the football team, and sociable, volunteering for dance committees. Bray is usually described as taciturn. When Bray left college to take up journalism in Detroit there was a William B. Robinson reporting for the Detroit Free Press, and Watsonhad a brother by that name. Bray and Robinson were both in New York by 1905. As John courted Margaret in Brooklyn, Watson married into an influential Port Washington family that ran trolley cars on Long Island from Nassau County into Queens.

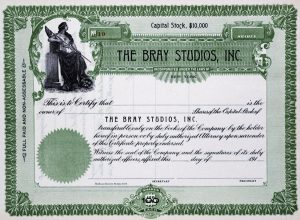

With guidance from Watson B. Robinson, Esquire, John and Margaret formed Bray Studios Incorporated. Robinson only held three shares of stock, but was on the company’s board of directors.

With guidance from Watson B. Robinson, Esquire, John and Margaret formed Bray Studios Incorporated. Robinson only held three shares of stock, but was on the company’s board of directors.

By this point in the career he was a partner in Frueauff & Robinson in room 1502 at 60 Wall Street. Numerous shell companies covering a variety of interests were registered there. A lot of ripples went out into the World from that ROOM. Rippling out to natural gas interests in Oklahoma and Kansas; to railroads in Ohio; and in buses and trolleys across the five boroughs of New York. John and Margaret had a friend in high places.

Pinkerton Pup

The Brays moved to a new apartment, 612 West 112th Street, remaining right off Columbia University’s campus. Bray Studios hired newspaper artist Carl Anderson to create the animated series PINKERTON PUP, about a police dog, for Paramount Pictures.

COLONEL HEEZA LIAR continued with Pathe. The First World War had broken out in Europe, and Heeza Liar sometimes reflected that conflict.

John Bray received the patent on a labor-saving technique of matting out backgrounds. While Bray did that, his employee Earl Hurd applied for a patent on his own process of drawing animated characters on clear celluloid sheets instead of paper.They formed the Bray-Hurd Patent Company as a trust for collecting licensing fees from any other animators daring to use their techniques.

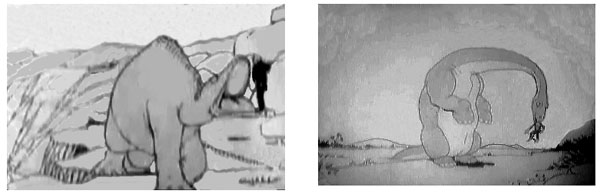

Bray routinely hyped the studio and boasted of hid own unique importance in creating the craft of animation, throwing salt in Winsor McCay’s wounds by releasing his own film titled GERTIE THE DINOSAUR. That “fake Gertie” cut into McCay’s bookings and profits, while ridiculing him artistically. At the end of the original Gertie, McCay is gently lifted onto his dinosaur’s back to be carried away. Bray’s Gertie CLOSES WITH a little monkey entering from the same side only to be roughly tossed aside.

Bray routinely hyped the studio and boasted of hid own unique importance in creating the craft of animation, throwing salt in Winsor McCay’s wounds by releasing his own film titled GERTIE THE DINOSAUR. That “fake Gertie” cut into McCay’s bookings and profits, while ridiculing him artistically. At the end of the original Gertie, McCay is gently lifted onto his dinosaur’s back to be carried away. Bray’s Gertie CLOSES WITH a little monkey entering from the same side only to be roughly tossed aside.

Bray Studios attracted interesting personnel. Jacob Leventhal, an architectural draftsman from Kentucky, arrived with a desire to make educational films. Leventhal’s cousin Frank Goldman followed, a talented stop-motion animator. Max Fleischer, recently art editor for Popular Science Magazine, brought his rotoscope machine, a way of doing more realistic animation.

Max Fleisher probably didn’t see cartoon characters scurrying across the floor when he stepped off the elevator at work, but who knows what went on in that magnificent mind of his.

1916 kicked off with Paramount Pictures ordering animation on a weekly basis. The contract specified that Bray Studios could provide animation exclusively to Paramount. Earl Hurd provided BOBBY BUMPS, following the prevalent newspaper strip formula of a boy and his dog.

John Bray secured a third patent. This one for putting animation foregrounds on translucent pages so a character could walk behind stationary objects. COLONEL HEEZA LIAR and BOBBY BUMPS both did well. Bray had another series titled MISS NANNY GOAT done by Clarence Rigby. POLICE DOG continued under Carl Anderson. There were a batch of cartoons done by well-known newspaper guys like Leighton Budd, Charles Wilhelm, and W. C. Morris.

To add a flourish of artsy distinction Bray invested in Charles Allan Gilbert’s little studio, located at Washington Mews, a gated-alley landmark off Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

Together they produced SILHOUETTE FANTASIES, a fancy paper-cut series.

Balanced against such artsy fare were the ribald high jinks of Paul Terry’s rambunctious FARMER AL FALFA.

Bray Studios covered all the bases, releasing more than seventy animated films during 1916. Pathé still wanted Bray cartoons. As a way around the exclusive Paramount contract, Watson B. Robinson incorporated Cartoon Film Services, housed right there in Bray’s space. Cartoon Film Service remained dormant until October when it elected new officers. Robinson remained president; Bray’s business and publicity manager Nathan Friend was named secretary; Bray’s art department manager Harry Bailey assumed the role of Cartoon Film Service treasurer. John Terry and Jerry Shields, freshly arrived from San Francisco, were the talent, creating half-a-dozen films for Pathe.

In January of 1917 Pathe made a deal to release William Randolph Hearst’s International Film Service cartoons. With no client to serve the Cartoon Film Service was disbanded. John Terry and Jerry Shields were gone. Bray also ended involvement with the Gilbert studio. Bray had Foster M. Follett working on the QUACKY DOODLE series.

John Terry’s brother Paul also departed Bray to work indirectly for Hearst. Paul Terry put out four TERRY CARTOON BURLESQUES through the A. Kay Company. ‘A. Kay’ derived from company president Allen Kander, an artist with Hearst’s Newspaper Feature Service.

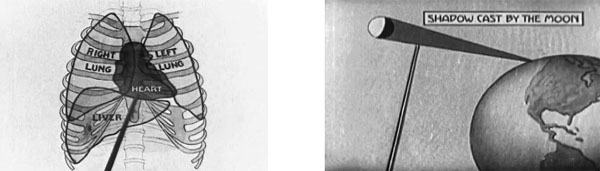

Bray Studios put Max Fleischer’s rotoscope to good use on training films for the military as the U.S. headed closer to involvement in Europe’s conflict. Fleisher and Jacob Leventhal were drafted and sent to Oklahoma as a team to make films for the army. They developed a style of ‘pointer stick’ technical animation.

Wallace Carlson came from Chicago. He’d animated on the OLD DOC YAK series for Selig Polyscope. He settled right in at Bray.

Wallace Carlson brought his own series DREAMY DUD, another cartoon about a boy and his dog.

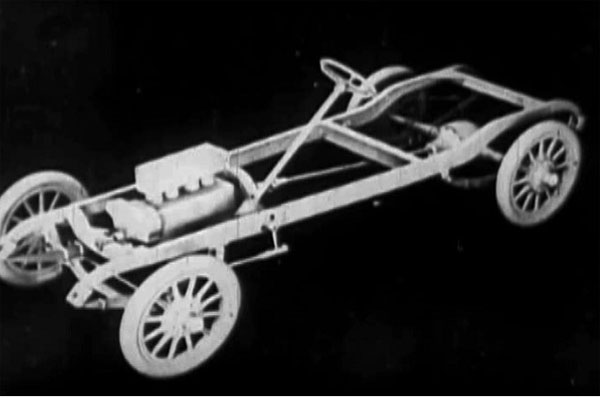

When Fleisher and Leventhal returned in 1919 after the war, a new direction got underway. COLONEL HEEZA LIAR was discontinued. Work began on a string of vocational training films. For auto mechanics, Frank Goldman assembled a car from scratch using stop-motion in ELEMENTS OF AN AUTOMOBILE.

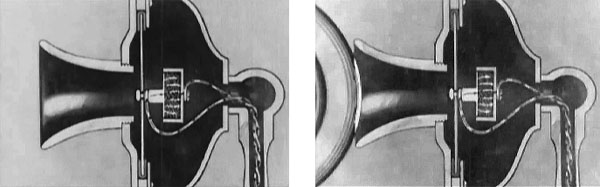

Fleischer and Leventhal made HOW A TELEPHONE TALKS.

These industrial films brought in good money. John McCrory, author of a book on animation, worked in the camera department. The Labor Department commissioned SAY UNCLE SAM explaining their hiring policies.. The U.S. Department of Agriculture engaged Bray for a cartoon about ticks infesting cattle.

Max Fleischer animated A WORD ABOUT MISS LIBERTY explaining construction of the Statue of Liberty. Fleischer also rotoscoped a little clown for his OUT OF THE INKWELL series.

Fleisher and Leventhal put their pointer stick style to use on a science series, covering subjects from the inner-body to outer-space.

Entertainment cartoons proceeded. Frank Moser had a DOWN THE MISSISSIPPI series.

Wallace Carlson, careful not to reveal much information, even did a short instructional film about animation.

The Bray Pictures Corporation formed August 1919. Stock wassold. The corporate structure grew more complex. Essentially, educational, industrial, and training films were considered one division. Entertainment films, including cartoons, were a separate division. Earl Hurd, Max Fleischer, and Wallace Carlso each ran their own cartoon units, the rest were supervised by Harry Bailey. Three Bray Pictures Corp stockholders, Watson B. Robinson, George J. Johnstone, and Leonard G. Lisner, had just founded the Lower Manhattan Realty Corporation.

Margaret Bray had gone into real estate, buying and quickly re-selling apartment buildings in the vicinity of Columbia University. Margaret bought those apartment buildings from the the New York Life Insurance Company. Columbia University president Nicholas Murray Butler sat on the board of directors for that company, alongside prominent bankers, publishers, industrialists, and transportation executives. The New York Life Insurance Company board included: a former U.S. Congressman; a Brigadier General; the New York State Commissioner of Education; the president of the New York Bar Association; an ex-Governor of Ohio; the governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston; the president of the Pennsylvania State Chamber of Commerce; a former Comptroller of the U.S. Currency; a former U.S. Secretary of Commerce and Labor; a former U.S. Treasury Secretary; and three former U.S. Interior Department heads.

John and Margaret moved in powerful circles. She assumed the role of socialite. But all was not sunshine and roses. Patent lawsuits swirled around John Bray. Aside from that, in September the studio separated from Paramount to have producer Samuel Goldwyn distribute. That move compelled Famous Players- Lasky Corporation, a division of Paramount Pictures, to start an animation department. Key personnel deserted to Famous Players. Nathan Friend. head of Bray’s business and publicity, went. Earl Hurd followed to supervise animations for PARAMOUNT MAGAZINE. Hurd brought BOBBY BUMPS with him. Bray’s production manager Harry Bailey defected as well, to be Earl Hurd’s assistant.

John and Margaret moved in powerful circles. She assumed the role of socialite. But all was not sunshine and roses. Patent lawsuits swirled around John Bray. Aside from that, in September the studio separated from Paramount to have producer Samuel Goldwyn distribute. That move compelled Famous Players- Lasky Corporation, a division of Paramount Pictures, to start an animation department. Key personnel deserted to Famous Players. Nathan Friend. head of Bray’s business and publicity, went. Earl Hurd followed to supervise animations for PARAMOUNT MAGAZINE. Hurd brought BOBBY BUMPS with him. Bray’s production manager Harry Bailey defected as well, to be Earl Hurd’s assistant.

The Brays’ next big move would be to partner with Hollywood hot-shot Sam Goldwyn. It was a decision that would disrupt their studio in many ways, and would effect the future of animation significantly.

I want to thank David Hornish for his persistent aid in researching this article. Dave is writing a book about Woody Gelman, and welcomes any information.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

DOWN THE MISSISSIPPI was part of the “Bud and Susie” series by Frank Moser. Those were done for Paramount Magazine, which Bray wasn’t involved.

I knew that Winsor McCay was born in Michigan, but I had no idea J. R. Bray was a Michigander as well. Tuebor!

You described Bray’s father as a “traveling Methodist Presbyterian minister,” but there’s no such thing. They’re separate denominations. (In Australia, the Methodist Church did merge with the Presbyterian and Congregational Union churches to form the Uniting Church, but that didn’t happen until the 1970s.) Alma College is a Presbyterian school; in fact, the sports teams used to be known as the Fighting Presbyterians. As the son of a Presbyterian minister, Bray would have been able to attend tuition-free. A Methodist minister’s son in Michigan would have been more likely to go to Albion or Adrian, the latter college being located near Bray’s birthplace of Addison.

“Margaret read Henry Ford’s book on assembly line production”: That would have been either Ford’s autobiography “My Life and Work”, or the later “Today and Tomorrow”, which covers the subject in greater detail. But the former book was not published until 1922, and the latter in 1926. They would have had no bearing whatsoever on the planning and organisation of the Bray studio. The only writing under Ford’s name to see print during the period covered in this post was an anti-smoking pamphlet called “The Case Against the Little White Slaver”, in which he asserted that burning cigarette papers are actually more dangerous than the tobacco itself!

All of Ford’s books were ghostwritten, of course; the man was barely literate. His best-sellers were the four volumes of “The International Jew: The World’s Foremost Problem”, which earned him a favourable mention from Hitler in “Mein Kampf”.

I’d like to have a look at some of the Silhouette Fantasies. That’s a very striking image.

The Colonel Heeza Liar cartoons had been discontinued already by 1917, but of course, returned in Dec. 1922. There is a distinct lack of L. M. Glackens, who mostly did one offs and fairy tales, but also created the famous Jester and Bird opening, which most people think first when they hear of the Bray cartoon. For anyone reading that is curious, my name links to the Bray Animation Project’s article on him, written by Mark Newgarden. Its a good read, as well as this.

Very interesting article, Bob! Can you fill in any more information about John McCrory? There are many legends about him. When he ran his own studio, he was known as “Scarfoot” McCrory, and supposedly ran his shop with an iron hand, actually physically beating the animators who didn’t produce as much work as the speedier guys. He produced the Krazy Kid cartoons, and the Life Cartoon Series. He also produced early sound cartoons such as “This and That From Here and There”. What more do you know about him? The Quacky Doodles Family was created by Johnny Gruelle, by the way.

I recently acquired a Keystone movie print, probably dating from the early 1930’s, of one of the Bray films you refer to by the series title, “Dreamy Dud”. The box, however, refers to the series as “Us Fellers”, suggesting that “Dreamy Dud” was only the name of the character. I’ve seen other internet listings referring to “Us Fellers” as well. A picture of the box is attached for your readers’ pleasure. Any way of determining for sure which is the correct series title?

That 8mm print is likely from the very late 30s or early 40s. “Dreamy Dud” was the moniker of the lead character in that series, but only in its pre-Bray iteration that was distributed by Essanay. Once Carlson was animating Dud for Bray, he was no longer ‘Dreamy’ and the series was called Us Fellers. There’s more info about this and most of the other Bray cartoon series over at the Bray Animation Project website.

John Randolph Bray had no problem playing fast and loose with the facts about his business. As best as I can gather, he was born 1979 in Addison, Michigan.

1879?

Thanks Bob, but check the photo for Margaret Till – unfortunately that’s not her in the photo you’ve posted…

Thanks for making the adjustments to the photos of Margaret Bray!

I want to thank David Hornish for his persistent aid in researching this article. Dave is writing a book about Woody Gelman, and welcomes any information.