Continuing my list of “Top Ten” favorite anime features, with a few I was personally involved with from my days with Streamline Pictures.

4. Laputa: The Castle in the Sky. Tenkū no Shiro Laputa. Produced by Studio Ghibli. Directed by Hayao Miyazaki. 126 minutes. August 2, 1986.

A perfect boy’s adventure cartoon! When the first anime fandom group tour to Japan, “Japanimation ’86”, was organized by Ladera Travel Service in Los Angeles (one of its travel agent was an anime fan), thirty of us from all over North America gathered in L.A. for a flight to two weeks in mid- to late August 1986 in Tokyo, ending up for the last couple of days in Osaka for the 1986 Japanese National Science Fiction Convention, Daicon V. You may be sure that I was one of the first to sign up for it. Ladera Travel had a hard time convincing the Japanese tourist agencies with which it worked that this tour did NOT want to visit the usual tourist sites, but Tokyo’s animation studios! One of the highlights of the trip was an afternoon tour of the offices of Tokuma Shoten (Tokuma Publishing Company), the publisher of Animage, Japan’s most prestigious monthly anime fan magazine. Tokuma Shoten had also financed the production of Miyazaki’s Nausicaä (heavily promoted in Animage), and bankrolled the creation of his Studio Ghibli, which had just released its first animated feature, Laputa: The Castle in the Sky, earlier that month. We were ushered downstairs into Tokuma’s screening room and treated to a full showing of Laputa; untranslated, as I recall. It didn’t matter; we could all recognize its excellence anyway. We must have been the first Americans to see it; the first American anime fans, anyway.

A perfect boy’s adventure cartoon! When the first anime fandom group tour to Japan, “Japanimation ’86”, was organized by Ladera Travel Service in Los Angeles (one of its travel agent was an anime fan), thirty of us from all over North America gathered in L.A. for a flight to two weeks in mid- to late August 1986 in Tokyo, ending up for the last couple of days in Osaka for the 1986 Japanese National Science Fiction Convention, Daicon V. You may be sure that I was one of the first to sign up for it. Ladera Travel had a hard time convincing the Japanese tourist agencies with which it worked that this tour did NOT want to visit the usual tourist sites, but Tokyo’s animation studios! One of the highlights of the trip was an afternoon tour of the offices of Tokuma Shoten (Tokuma Publishing Company), the publisher of Animage, Japan’s most prestigious monthly anime fan magazine. Tokuma Shoten had also financed the production of Miyazaki’s Nausicaä (heavily promoted in Animage), and bankrolled the creation of his Studio Ghibli, which had just released its first animated feature, Laputa: The Castle in the Sky, earlier that month. We were ushered downstairs into Tokuma’s screening room and treated to a full showing of Laputa; untranslated, as I recall. It didn’t matter; we could all recognize its excellence anyway. We must have been the first Americans to see it; the first American anime fans, anyway.

(It was after we had just seen Laputa that Yasuyoshi Tokuma, the elderly founder of the company, was helped into the room by a couple of younger staffers and made his speech – translated by a nervous employee – about, despite Japan’s failure to win World War II, he was glad to see that Japanese culture was finally spreading into America anyway through its animation, and he was happy to recognize us as among the first Americans to accept the Japanese influence. Most of the tour group was talking about what we had just seen and did not really listen to him. Mr. Tokuma was the only proponent of Japan’s 1930s-1945 military government that I ever met. Considering the Japanese military’s habit of starving and murdering its Western prisoners of war and interned civilians, I can’t feel sorry that Japan lost the war, despite my admiration of its anime.)

Streamline Pictures also recognized the superiority of Laputa. It was Streamline’s first licensed title, a couple of years before I joined the company, for two six-month licenses from March to August 1989, and from September 1989 to February 1990. Tokuma refused to let Streamline renew the license again. American anime fans loved everything that Studio Ghibli (which is to say Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata) produced. Streamline and all the other American anime licensers kept getting letters from anime fans urging us to get Studio Ghibli’s movies for American home videos. Unfortunately for us, Ghibli (and its boss at the time, Tokuma Shoten) kept holding out for a major American movie producer-distributor, which it finally got with the Walt Disney Company in 1996.

Streamline Pictures also recognized the superiority of Laputa. It was Streamline’s first licensed title, a couple of years before I joined the company, for two six-month licenses from March to August 1989, and from September 1989 to February 1990. Tokuma refused to let Streamline renew the license again. American anime fans loved everything that Studio Ghibli (which is to say Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata) produced. Streamline and all the other American anime licensers kept getting letters from anime fans urging us to get Studio Ghibli’s movies for American home videos. Unfortunately for us, Ghibli (and its boss at the time, Tokuma Shoten) kept holding out for a major American movie producer-distributor, which it finally got with the Walt Disney Company in 1996.

Laputa, written as well as directed by Miyazaki, has to be considered as alternate-world science fiction. Several centuries prior to the setting of this story (which is apparently the late 1880s), this world had a civilization based on power crystals (volucite) that enabled flight and great sky-cities. This ended when the power crystals were exhausted. The sky-cities all fell to Earth, except for the legendary vanished city-kingdom of Laputa, powered by a giant and inexhaustible volucite crystal. There are primitive aeroplanes and dirigibles, but nothing powered by the crystals.

The protagonists are a young farm girl living alone, Sheeta, who is taken away for unknown reasons by government agents led by the plainclothed Colonal Muska; and a young miner, Pazu, in a deep mine where adult miners are desperately searching for a new vein of power crystals. The story gradually reveals that the government wants Sheeta for her necklace which is a large power crystal; that Sheeta is a descendant of the rulers of Laputa, who gave up their aloofness to live as ordinary humans; that Muska is also descended from Laputans, and wants to force Sheeta to reveal where Laputa is today and how to control it, so he can use it to conquer the world; that Sheeta is trying to escape from Muska, with Pazu’s help once she meets him; and the involvement of all three with Laputa’s flying robots, and with Ma Dola’s gang of sky-pirates (her sons) in her dirigible, the Tiger Moth.

The protagonists are a young farm girl living alone, Sheeta, who is taken away for unknown reasons by government agents led by the plainclothed Colonal Muska; and a young miner, Pazu, in a deep mine where adult miners are desperately searching for a new vein of power crystals. The story gradually reveals that the government wants Sheeta for her necklace which is a large power crystal; that Sheeta is a descendant of the rulers of Laputa, who gave up their aloofness to live as ordinary humans; that Muska is also descended from Laputans, and wants to force Sheeta to reveal where Laputa is today and how to control it, so he can use it to conquer the world; that Sheeta is trying to escape from Muska, with Pazu’s help once she meets him; and the involvement of all three with Laputa’s flying robots, and with Ma Dola’s gang of sky-pirates (her sons) in her dirigible, the Tiger Moth.

Miyazaki based the movie very distantly on Laputa, the flying city of head-in-the-clouds scientists in the third part of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. Since “laputa” (correctly “la puta”) means “the whore” in Spanish (and don’t think that Swift didn’t know that), the American title today is just The Castle in the Sky. The two-hour-+ movie starts off with the exciting pre-opening credits scene of the Dola gang capturing the luxury dirigible on which Sheeta is travelling, and her falling from it; and it never slows down – except where Miyazaki has deliberately planned a break to let the audience rest before the next action sequence. It contains both suspense and humor, often mixed together. It features two 10- or 11-year-olds who can beat most of the adult antagonists because of their intelligence; then reveals their antagonist, Muska, to be a master villain who is ahead of both of them. It features an exotic 19th-century “steampunk” setting. It features “boys’ toys” machines like the Tiger Moth pirate airship; the government’s Goliath dirigible warship; and the Laputan flying robots. It features the mystery of whether Laputa is mythical or real; and if real, where is it? It features Joe Hisaishi’s stirring music. I must have seen it a dozen times by now, and I am eager to see it again.

5. Robot Carnival. Produced by A.P.P.P. Co., Ltd. Producer: Kazufumi Nomura. 90 minutes. July 21, 1987.

I did not see this one until I went to work at Streamline Pictures. Robot Carnival does not have a traditional single director. A.P.P.P.’s founder/producer, Kazufumi Nomura, went to nine animators, most of whom had little or no directing experience, and offered to subsidize a ten-minute short film from each, about whatever they wanted – except that it had to feature a robot or robots prominently. Nomura packaged them together into this feature, and commissioned the music for them. A.P.P.P. stands for Another Push Pin Production, by the way.

I did not see this one until I went to work at Streamline Pictures. Robot Carnival does not have a traditional single director. A.P.P.P.’s founder/producer, Kazufumi Nomura, went to nine animators, most of whom had little or no directing experience, and offered to subsidize a ten-minute short film from each, about whatever they wanted – except that it had to feature a robot or robots prominently. Nomura packaged them together into this feature, and commissioned the music for them. A.P.P.P. stands for Another Push Pin Production, by the way.

It may be misleading to just say that Robot Carnival was released on July 21, 1987. If I understand correctly, it was an art film and did not have a wide theatrical release in Japan. It got its most widespread release in the U.S. from Streamline Pictures. It was included as a sneak preview in a Festival of Animation that Streamline put together at the Spreckles Theater in San Diego on August 2-4, 1990, for the attendees of the 1990 San Diego Comic-Con. (The other features were Laputa, Twilight of the Cockroaches, Akira, and sneak previews of Lensman and Manie-Manie (aka Neo-Tokyo)). Streamline released Robot Carnival theatrically in January 1991, and as a Video Comics VHS in December. (IMDb says that Robot Carnival’s U.S. release date was March 15, 1991. IMDb is wrong. Robot Carnival premiered at the Cinema 21 in Portland, Oregon on January 25-31, 1991.)

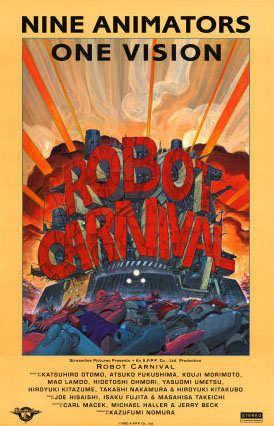

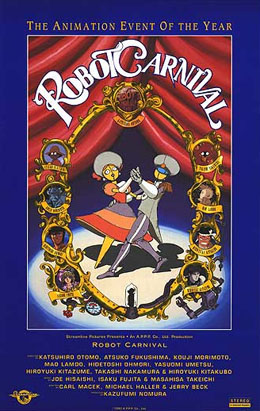

Robot Carnival presented “Nine Animators – One Vision”, to quote one of its two theatrical posters. They were:

Opening. No title. Directed by Atsuko Fukushima & Katsuhiro Otomo. An s-f black comedy. A tiny isolated desert community is thrown into a panic by the news that the Robot Carnival is coming. It turns out to be a gigantic decaying mechanical music machine that travels on tanklike treads, crushing buildings, whose musical instruments and metallic dancers shoot rockets and bombs that blow up what is not crushed, while playing the Robot Carnival March. The surviving villagers on a bluff watch the huge machine trundle into the distance. Pantomime.

Starlight Angel. Directed by Hiroyuki Kitazume. Two giddy teenage girls in a futuristic very Disneylandish robotic amusement park are separated when one discovers the other making out with her boy friend. She runs by herself in tears into a virtual reality ride. The ride molds itself to the rider’s emotions, but since the girl is heartbroken and bitter, the ride turns into a giant, menacing robot. She is saved when one of the park’s comic-relief robots turns into a handsome boy in a robot suit, which he takes off to fight the monster. Essentially a pantomime music video for teenage girls.

Franken’s Gears. Directed by Koji Morimoto. A black comedy inspired by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, or more likely, all of Hollywood’s Frankenstein movies. A very elderly Mad Scientist, who it is implied has been trying to make a giant robot for most of his life with many electric sparking and “voop voop” devices, finally succeeds. The giant robot arises and slowly begins to mimic the scientist’s movements. The delighted scientist capers in joy until he trips and falls down. The robot, mimicking him, falls on top of him, crushing him. Pantomime.

Deprive. Directed by Hidetoshi Ōmori. The opening shows human girls and same-sized robotic android men living peacefully together. Suddenly alien conquerors invade, kidnapping “the girl”. Later, a handsome hero is seen speeding toward the invaders’ headquarters, avoiding all their attempts to stop him. He tries to rescue the girl, but is captured by the alien commander, an arrogant young man in garish KISS-style makeup. The hero is tortured and revealed to be the earlier robotic android in human guise, upgraded into a combat soldier. He escapes and, after more fighting with the invaders, rescues the girl who recognizes him because he still carries her locket. Pantomime.

Presence. Directed by Yasuomi Umetsu. In a vaguely British future society, there is much prejudice against robots made to look like humans. A young inventor builds a beautiful girl; then, terrified of being found out, disassembles her despite her pleas to be left alive. He is haunted by her memory for the rest of his life, and on his deathbed, his soul is welcomed into the afterlife by the girl’s. Dialogue.

Cloud. Directed by Mao Lamdo. A robot little boy sees the history of mammalian and human life in the clouds that blow past in the sky. Pantomime.

A Tale of Two Robots. Chapter 3, Foreign Invasion. Directed by Hiroyuki Kitakubo. Gonzo comedy. 19th-century Japan is invaded by an American Mad Scientist, “Jonathan Jameson Falkenson III”, in his electricity-powered giant robot, “my Tinker Bell”. He is opposed by a group of Japanese teens in their steam-powered giant robot. After misadventures by both, Japan is “victorious” despite being trampled underfoot by both robots. The Mad Scientist promises to return, but there is no sequel. Dialogue.

Nightmare. Directed by Takashi Nakamura. In Tokyo at night, when everyone is asleep, a robotic leader in a red hat & cloak awakens demonic machines, inspired partly by Hiernonymus Bosch but mostly by the “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence in Disney’s Fantastia. Their takeover of the city is witnessed only by a human drunkard asleep in an alley, who wakes up and is terrified. The robot pursues the fleeing coward, who keeps escaping all night. At sunrise, the robot and machines all disappear, but the human is stranded on a construction girder high above Tokyo. Pantomime.

Ending. No title. Directed by Atsuko Fukushima & Katsuhiro Otomo again. It is apparently several years after the opening sequence. The Robot Carnival is still trundling slowly through the desert, but it is considerably more decrepit. It crests a high bluff and finally breaks down completely. Pantomime; much shorter than the other sequences.

Closing credits, interspersed with scenes of the Robot Carnival when it was brand new, surrounded by cheering people, setting out on its mechanical voyage.

Epilogue. Directed by Atsuko & Katsuhiro Otomo. A desert traveler finds the ruins of the Robot Carnival, including a little silvery globe containing a tiny robot ballerina. He brings it home for his children. They are delighted, until it explodes, killing everyone. No “everybody survives”, like in Western animation.

There are several differences between the Japanese version of Robot Carnival and Carl Macek’s Streamline Pictures version. Firstly, two sequences have different titles. A Tale of Two Robots is Strange Tale of Meiji Machines: The Chapter of the Red-Haired People’s Invasion (a joke, because the American Mad Scientist is bald, but “Red-Haired People” is one of the Japanese people’s common names for Western foreigners during the late 19th century), and Nightmare is Chicken Man and Red Neck (the “chicken man” is the cowardly drunk, and “Red Neck” is the scarlet-cloaked robot). Secondly, in the Japanese version of A Tale of Two Robots, the American Mad Scientist’s dialogue is the same voice track as the American, but is subtitled in the old Japanese way, handwritten and vertically, to the right side of the screen. The Japanese youths’ dialogue did not need to be translated. In the American version, all the dialogue is in English and the Japanese subtitles are removed. Thirdly, in the American version, the Epilogue comes right after the Ending, followed by new English-language closing credits without the scenes of the Robot Carnival when it was new. This was because A.P.P.P. Co. no longer had the art for those scenes, and it would have been too difficult/expensive to extract them from the Japanese film.

There are several differences between the Japanese version of Robot Carnival and Carl Macek’s Streamline Pictures version. Firstly, two sequences have different titles. A Tale of Two Robots is Strange Tale of Meiji Machines: The Chapter of the Red-Haired People’s Invasion (a joke, because the American Mad Scientist is bald, but “Red-Haired People” is one of the Japanese people’s common names for Western foreigners during the late 19th century), and Nightmare is Chicken Man and Red Neck (the “chicken man” is the cowardly drunk, and “Red Neck” is the scarlet-cloaked robot). Secondly, in the Japanese version of A Tale of Two Robots, the American Mad Scientist’s dialogue is the same voice track as the American, but is subtitled in the old Japanese way, handwritten and vertically, to the right side of the screen. The Japanese youths’ dialogue did not need to be translated. In the American version, all the dialogue is in English and the Japanese subtitles are removed. Thirdly, in the American version, the Epilogue comes right after the Ending, followed by new English-language closing credits without the scenes of the Robot Carnival when it was new. This was because A.P.P.P. Co. no longer had the art for those scenes, and it would have been too difficult/expensive to extract them from the Japanese film.

Another difference is that the scenes are sometimes in different orders. When Streamline licensed Robot Carnival, A.P.P.P. sent the negatives for the different sequences separately. There was apparently some technical reason that I don’t understand for the 35 m.m. sequences to be spliced together in a different order for theatrical projection and for the VHS video tape. The Sci-Fi Channel may have showed the feature with the sequences in a third order for the convenience of inserting the commercials into it.

When Streamline released Robot Carnival, we got letters asking when we would release the next chapter of A Tale of Two Robots. When we explained that the “To Be Continued” was a joke and that no further sequence existed, we were asked if we couldn’t commission one?

So why do I rank this as one of my Ten Favorite Japanese Anime Features? Each of the nine sequences is a little gem, rich in detail. (Or eight are. I can do without Cloud.) There is humor, suspense, drama, comedy, and pathos rapidly alternating, each with a distinct art/animation style. Most of the nine directors have gone on to much bigger and better things in anime. Most sequences have great music, mostly by Joe Hisaishi, with some by Isaku Fujita and Masahisa Takeichi; and the couple with dialogue also provide variety. Robot Carnival never gets boring, except for the gentle Cloud, and even that is an imaginative change of pace. Some reviewers have thought that it is the best sequence in the feature, which just proves that Robot Carnival has something for all tastes.

Below is the Sci-Fi Channel’s broadcast of Streamline’s Robot Carnival. You’ll note I share a credit for “Publicity” with Carl’s wife, Svea. Jerry Beck gets two credits, one as an “Associate” (Associate Producer, I believe) and as Production Supervisor (for the English Language version).

This column has gone on way too long with only two titles. I’ll continue the rest of my “Top Ten” next week.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Fred Patten (1940-2018) was an internationally respected comics and animation historian. He has written about anime or comic books for publications ranging from Animation Magazine and Alter Ego to Starlog. He was a contributor to The Animated Movie Guide (2005), and is author of Watching Anime, Reading Manga (2004, Stone Bridge Press), a collection of his best essays, and Funny Animals and More (2014, Theme Park Press), based upon his early columns here on Cartoon Research. He passed away on November 12th, 2018.

Those living in Los Angeles to their chance a year later when the film was screened at the 2nd Los Angeles Internation Animation Celebration festival I recall.

And I bet this was the “JAL” dub too, and while Macek had nothing to do with this, some actors that had worked for him were on it like Barbara Goodsen as Pazu (which wasn’t bad to me at all since I didnt’ much care for the older sounding voice they went with in Disney’s vesion). This first dub did receive an R2 DVD release in Japan over a decade ago.

I remember first finding that out and realized how much that made sense for the type of thing you do in animation (storyboarding), though another phrase I’ve seen is “Another Push Pin Planning”.

Most sources identify it as an OAV (or OVA, whatever you want to call it by this point). It made sense to me if it was since very often stuff like this was getting funded as video releaese in Japan at the time. There was a market for it before the bubble burst.

At least we have you here to clear things up! Streamline’s edition also saw a reissue as a budget-priced VHS tape from Best Film & Video some years later (that’s the version I first had). Lumivision Corporation would also release the film alongside a few other Streamline titles in the 90’s too.

Incidentally Fred, unless the segments were different theatrically from where they were on video, the way it plays out on the copies I’ve seen was this…

OPENING

STARLIGHT ANGEL

CLOUD

DEPRIVE

FRANKEN’S GEARS

PRESENCE

A TALE OF TWO ROBOTS

NIGHTMARE

ENDING/EPILOGUE

When it was released in Japan on OVA, the segments were originally set up differently with Franken’s Gears starting things off after the opening.

Which I can see why we wouldn’t get that, the English title was a clever pun none the less.

The American character in the original was also interestingly done by a someone named James R. Bowers. And while I suppose he did a fine job with what he was given, I still like Steve Kramer’s take on the character in Streamline’s version.

One thing left untranslated I recall in this segment was a book that was inside the Volkeson’s robot that was subtitled in Japanese as “The Travels of Marco Polo” (which I got immediately).

In anime terms, they didn’t have a “textless” version of those scenes for Streamline to insert their credits in.

Sci-Fi’s handling of the film mirrored it’s VHS/LD release for the most part. I do recall often during “Saturday Anime”, if they had a film that ended shorter than the intended running time, they would play a short extract from “Robot Carnival” to pad the time. I remember one of these where they show the opening, then Deprive, then show the end credit sequence.

One thing from the Streamline release that still sticks in my mind is the added bit at the very end stating “In Memory, Lisa Michelson (1958-1991)”. I forget what we lost because of her passing in my later years in fandom, discovering other titles she was on in her brief carrer like one of the girls in My Neighbor Totoro or playing the title role in Kiki’s Delivery Service. In Robot Carnival, she was both the doll in PRESENCE and one of the good guys in TALE OF TWO ROBOTS. She will be missed.

Ha-HAW!

I like Cloud! I even found Mao Lamdo on Twitter too! He follows me now!

Too bad this video cuts out before Lisa Michelson’s dedication though. I remember seeing that on Sci-Fi too.

*sigh* I have to wait? 🙁

In the meantime, check out my stash of cels from this fine cinematic opus….

https://www.flickr.com/photos/sobieniak/sets/72157647189632268/

I am most familiar with the arrangement of “Robot Carnival” as the Opening, Starlight Angel, Franken’s Gears, Deprive, Presence, Cloud, A Tale of Two Robots, Nightmare, Ending/Epilogue, which I think was the video release. I didn’t see the theatrical version very often, although I sure remember lugging those Goldberg metal 35 m.m. film containers from Streamline’s film storage room out for UPS or DHL to transport them to the theaters booking it. The Goldberg movie cans, which held up to six 35 m.m. reels, weighed about 55 lbs. apiece, and “Robot Carnival” took two of them.

The Japanese 19th-century description of Americans and Europeans as “Red-Haired People” was not a compliment, but it wasn’t as insulting as “Foreign Devils” or “Big Noses”. Fascinatingly, Castorp, the German in Miyazaki’s 2013 “The Wind Rises”, has a notably huge nose.

Streamline almost always got the theatrical anime that it licensed minus any textless version of the credits, with a breezy “Sorry, but we threw that out long ago”. That was why we had to create new American credits, without any art that was in the Japanese credits, which the anime fans were sure to complain about. “The Castle of Cagliostro”, “Golgo 13”, “Fist of the North Star” …

A lot of people liked “Cloud”! Tastes differ.

Aside from ‘Night on Bald Mountain,’ I’ve always felt there was a second obvious Disney influence on the ‘NIghtmare’ segment of ‘Robot Carnival’ – the chase sequence in ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.’ The drunk has Ichabod Crane’s big nose and skinny neck, and the pursuing robot sports that flowing red cape a la the Headless Horseman.

I pretty much thought the same thing, I think Cartoon Network even brought it up in a bumper when they aired this film back in ’95, saying this segment combined both influences. Both this, Vampire Hunter D and Twilight of the Cockroaches were aired around that time and was my first exposure to these!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s_x7l_7O8Pg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lmS_cz4k6c4

Yes, that’s obvious.

I saw a dubbed version of Laputa at the Tampa Theater during a theatrical run. I can only assume it was the JAL dub. Though it had some awkward parts, I thought it was good in comparison to the ones that were mostly around at that time. What still stands out to me is how the audience stood and applauded when Pazu saves Sheeta from the burning tower. I always thought Disney should have released Laputa theatrically before doing so with Princess Mononoke.

Certainly was a missed opportunity there.

My favorite IMDb error was about some World War II animated short — I no longer remember which one; but not a regular theatrical cartoon from any major studio — expressing the public’s surprise and anger over the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, that IMDb said was released in 1939. I sent IMDb a note saying that, while I didn’t know when it was really made & released, it could not have been before the actual attack on Dec. 7, 1941. My guess from the context of the outrage was early 1942. I sent this to IMDb shortly before my stroke in March 2005. As far as I know, IMDb never corrected it. I hope that some Cartoon Research reader knows what this film was, so I can check again today and see if IMDb ever changed its entry.

I wish I knew. That is pretty bad how IMDB can be sometimes simply based on “user-submitted” information.