Continuing our overview of the Argentine animated ad in four parts. Today, part 2: Manuel García Ferré.

García Ferré is best known as an independent producer, but since advertising was the backbone of his not so small usine, it works perfectly as a showcase for the whole.

Manuel García Ferré (1929-2013) was a Spanish-born cartoonist, director and editor who built his career in Argentina. He was known as the creator of famous children’s characters, comics, cartoons, advertising, animated series, animated feature films and a true publishing industry generated around his creatures. After his arrival to Argentina in 1947, he worked in advertising agencies, studied Architecture and prowled magazines with an art portfolio stucked under the arm. In 1952, his character Pi-Pío was accepted in the children’s magazine Billiken. Pí-Pío (a little chick dressed as a cowboy) lived extravagant adventures in a universe where many of Ferré’s characters first appeared. His naïf style was nothing like that of his colleagues, fitting perfectly to the dreamlike universe proposed by his stories. García Ferré was interested in animation from the very beginning: shortly after arriving in Argentina, he started to make cartoons with a Bolex, in 16 mm, to sell copies of the films to the projector shops, as samples offered to the buyers. Around 1959, Ferré also directed his efforts towards advertising animation, for which he created numerous characters, such as the “Mamita wool” cats, a celebrated hen that promoted mayonnaise and other similar fauna. Some of them would become more famous than what they advertised, because Ferré had a particular trait: in many cases, he retained the rights over his advertising creatures, who also participated in his more personal work, so that the differences between his personal dreamlike world and the advertising one were constantly blurred. One of these “commercial creatures” caught on with the public. His name was Anteojito and he was a little boy carrying a pair of glasses bigger than his head, accompanied by a kindly uncle who wore an ominous mask, rightly called “Antifaz” (“mask”). “Antifaz” was goodness personified and yet his black mask gave him an unsettling appearance. And that’s the fuel that made Ferre’s creations work. His was a universe made of contrasts, where characters could become their opposite, where silly word puns gave way to fake Latin or strange Lovecraft-like curses such as “Intríngulis Chíngulis”; where surrealism was literally used to sell candy. Dalí would have been delighted.

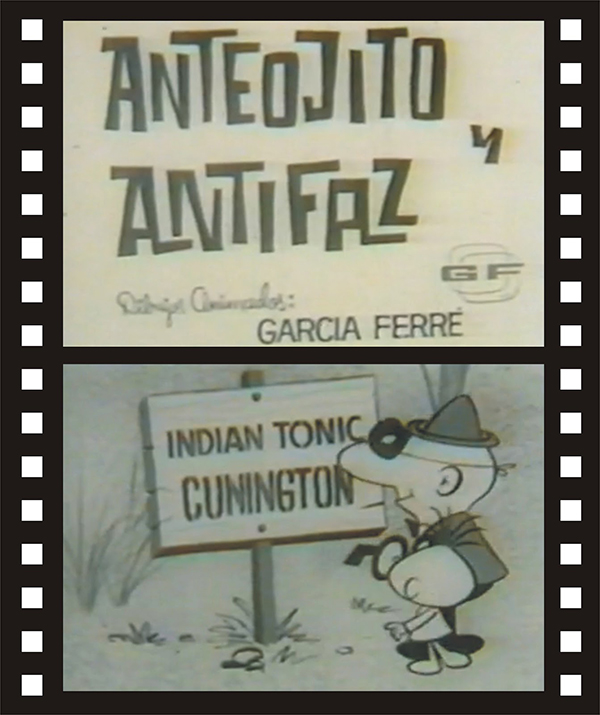

Anteojito Ad.

In 1964, Ferré launched the magazine “Anteojito”, from where he developed a publishing enterprise in parallel to his production company. It was a resounding success.

Anteojito magazine cover (first issue)

Around 1967, in partnership with Osvaldo Domínguez (in charge of photography), he started the production of an animated series for Channel 13. “Las Aventuras de Hijitus” (originally “Minutos Hijitus”) were daily episodes of one minute of animation around the adventures of the main character, with the corresponding cliffhangers. In 1942, the lushful produced Dante Quinterno’s “Upa en Apuros” did not appeal to the public. Hijitus was its exact opposite: a rather synthetic animation, where Ferré’s original designs had suffered some standardization imposed by the hands of several animators, and a rushed production (given that the minute of animation had to be produced in exactly one day), achieved an unexpected success that made the series be exported to all of Latin America and cemented Ferré’s film career.

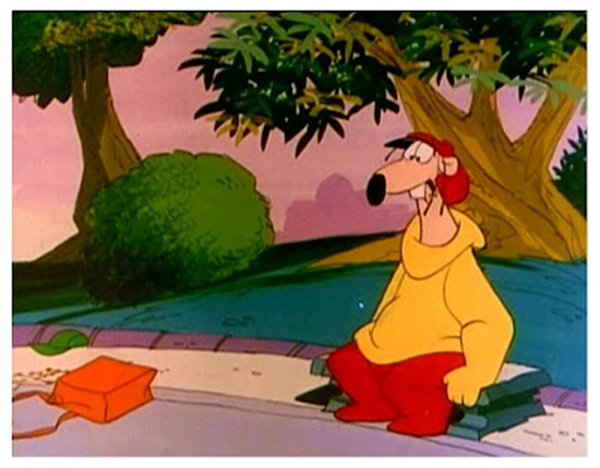

Hijitus and his foes.

“Larguirucho” character from “Las aventuras de Hijitus” became wildly popular. Originally a second fiddle of the bad guys, he moved to team with the good ones, but he often betrayed both. Garcia Ferré included him on most of his features.

The production of a daily minute allowed Ferré to exercise his muscles: if he could get half an hour of animation in a month, the production of feature films was not far behind. Ferré expanded his company, and, from the 1970s onwards, he was producing from animated feature films to television programs, along with a wide variety of magazines and books, while experimenting with different animation techniques. Ferré’s periodical feature became an obligatory outing in Argentina: “Mil intentos y un invento” (1972), “Las aventuras de Hijitus” (compiling the tv show, 1973), “Trapito” (1975), “Ico, el caballito valiente” (1983), “Manuelita La Tortuga” (1999), “Corazón, las alegrías de Pantriste” (2000). In 2012, a year before his death, he released his last film, “Soledad y Larguirucho”, a story in which he combined drawings with real actors.

Garcia Ferré’s “Trapito” ad.

One detail (which did not go unnoticed by critics) is that in his feature films, Ferré seemed to have lost some of the wild naivety of his beginnings to gradually fall under the ersatz-Disney shadow he had managed to elude until then, becoming sentimental and a bit syrupy. At least, that’s what the critics said. The public didn’t give a damn and stampeded to see his productions every time. Manuel had one more talent: he could move his ears in the right direction.

Garcia Ferré’s “Ico, el caballito valiente” movie poster.

Alberto Grisolia.

Alberto Grisolía is an Argentine animator, active since 1967 until today. He began his extensive career in Producciones García Ferré, painting acetates for the strip Hijitus, to later become an animator. He continued animating until 1999. From 1982 to 1995, he also worked for Hanna-Barbera and several animated feature films, series and advertising shorts produced both in Argentina and abroad.

AG: I was only a character animator, I’m not an author. I worked for many productions. I’m happy to have directed a sequence combining classic animation with CGI for the film “Patoruzito 2”, something that at that time was unusual.

I studied Fine Arts and then I did a year at the IDA Institute, with Garaycochea (a celebrated Argentine cartoonist). Without thinking on it, I landed on the animation art. At the age of 18 I entered García Ferré’s, and I quickly went from tracing and painting (I had no brush line quality on cels; it was admirable to see the ease with which the tracers finished the lines to perfection) to Inbetweening. Then I progressed with the help of the animators who worked there.

They taught me things like how to rotate the characters in space, or how to work with inbetweens. We were producing the Hijitus series and the black and white drawings were opaqued. García Ferré saw that color TV was the next thing and backgrounds and characters went from grayscale to colors (Color TV arrived to Argentina in the ‘70s). The colors had to function as gray values, since TV was still in black and white.

In 1968, when I entered, the studio occupied at least three floors, at Viamonte 723. In one floor was the publishing house. On another, was the animation studio; and on the other, Inbetweening, Tracing and Painting, plus a sector for Backgrounds and Filming, Sound and Edition. A minute a day was made, which is a lot, all personally checked by García Ferré. At that time only the Hijitus series was in production.

9: What were the production mechanics like? Separate teams? Or did they overlap functions?

AG: I don’t remember exactly how many people there were, but the ideas and the script were in charge of Nestor D’Alessandro together with García Ferré; and his work could be enriched with the contribution of the animators. Then came a quick storyboard by Nestor Córdoba (Animation Director), who, together with Pérez Agüero, was also in charge of the layouts. Then it went to Animation, with Horacio Colombo, Jorge Benedetti, Natalio Zirulnik, Roberto García, Hugo Casaglia, Arnoldo Cirilli and maybe some others. I was on another floor with Inbetweens, which followed, along with Laureano López, Carlos Paura, Beatriz Baldi, Raúl Barbero, Roberto Bat and more (we were around seven people). The sound was already transcribed in a sheet for the animators. The voices were Pelusa Suero and D’Alessandro (Hijitus’ voice, after some speed up), and eventually some guests. After checking, it went to Tracing and Painting, in charge of Néstor Domínguez, with Susana Macaya, Mirta Fasanela, Gladis and Elisa Esquivel, Jorge Somma, among others. The backgrounds or sets were in charge of Walter Canevaro and Carlos Barbieri, and later, when feature films started to be produced, Hugo Csecs.

Cover by Hugo Csesc for Editorial Abril.

Everything was checked shot by shot in Filming, in charge of Osvaldo Domínguez, García Ferré’s partner (with Raul Lamponi). Then Editing and Sound, in charge of sound engineer Francisco Busso and Luis Busso. The final result was checked and corrected by Ferré himself or Domínguez. And then, a rush to the channel, every day. The need for daily delivery meant that we found ways to reuse backgrounds and animation, which was already prepared from the script. By 1970, the first feature film, Mil intentos y un invento (“A Thousand Tries and One Invention”), was already in production.

“Mil Intentos y un Invento” ad.

9: Do you know how they developed the plots or how much Ferré was involved in the development of the stories? Could the animators intervene or was everything closed beforehand?

AG: García Ferré created the general situations together with Nestor D’Alessandro. Usually a first story was put on a blackboard, and everyone would give their opinion on each sequence. Although he received ideas from the animators, only what he approved was done. He was very creative, and don’t forget that at the time he was running the publishing house, with all its magazines, and the film production company (usually with a feature film in the works), plus the TV stuff. Not only was he running the overall company, he was also in charge of the contents. He might take some idea from the animators that he liked, perhaps with modifications, but it all went through him.

“Jack” chocolate bars came with those García Ferré figures inside. Some people would do anything to get this collection.

At one point he moved the studio to another larger building, 1386 Corrientes Avenue, also occupying more than one floor. I don’t remember the exact date.

9: The studio diversified: not only Hijitus but also the different comics for magazines. Do you know or remember if there was interaction between illustrators-comic creators and the animation studio? Did the studio change when they started to produce feature films?

AG: Yes, in the feature films some of the magazine’s illustrators participated in the animation, even creating some characters. For example, Jorge and Fabián de los Ríos. Or Palmeoli and Falin, in the movie “Trapito”; and later in “Manuelita”, although they were already more prepared as animators. Of course, the team was also enlarged. The later contribution of Roberto Barrios, an excellent draftsman and animator with knowledge of digital techniques, who was very useful to García Ferré in the new era, was important. Fabián de los Ríos (Jorge’s son) was another of those who first adapted in this sense, then the others followed.

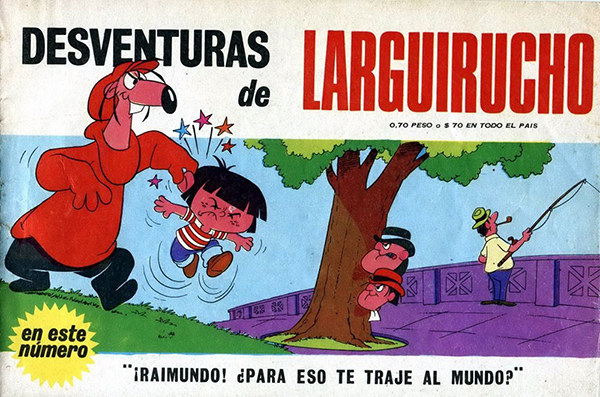

Larguirucho comics cover.

The publishing house had people in charge of the production of each magazine, and many external collaborators. For the comics published in the magazine Las Aventuras de Hijitus, D’Alessandro wrote the scripts and Falin did the drawings, with his inkers finishing the originals. In the series of comics published in Desventuras de Larguirucho, D’Alessandro and Rafael Bossio wrote, Raúl Barbero drew in pencil and Roberto Bat inked. At one time, I also inked with them. Anteojito and Petete magazines had many external collaborators, but artists like Jorge de los Ríos worked inside the studio. We also produced material for the outside. For example, in 1990, within Producciones García Ferré, we animated some scenes from the movie A Troll in Central Park for Sullivan Bluth.

Petete magazine cover. “Petete” was an animated puppet.

9: You did a lot of work as a freelance animator for Hanna-Barbera, Mordillo’s shorts or in advertising. What was that process like?

Antifaz

So far Grisolía, so far García Ferré. Enough to add, by way of a colophon, that in an environment known for its hot blooded pressure and deadly deadlines, everyone agrees that working for García Ferré was a quasi-celestial experience. Intríngulis Chíngulis!

NEXT WEEK: Catú.

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

Lucas Nine is an Argentine artist: illustrator, graphic novel author, animator and director of animated films. His work has been awarded several times and published, exhibited and screened in Argentina, Brasil, Mexico, Canada, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Hungary, Netherlands and Japan. Check out his animation and artwork online:

That Hijitus cartoon is quite good, although much of it went right over my head. The animation compares favourably to what most of the U.S. studios were turning out in 1969. Hijitus and Oaky remind me a little of Scrappy and Oopy in the old Columbia cartoon series.

On a whim I discovered that some of Garcia Ferre’s animated features are available on YouTube with English subtitles. I just watched “Ico, el caballito valiante” and enjoyed it very much. I was amused to see that Larguirucho was one of the main characters, a testament to his popularity. The one thing I didn’t like was its musical score, basically a random sequence of disjointed needle drops like a Stanley Kubrick movie. But the original songs are charming.

Thank you again, as always, for bringing to my attention these cartoons that I otherwise would never have known existed.