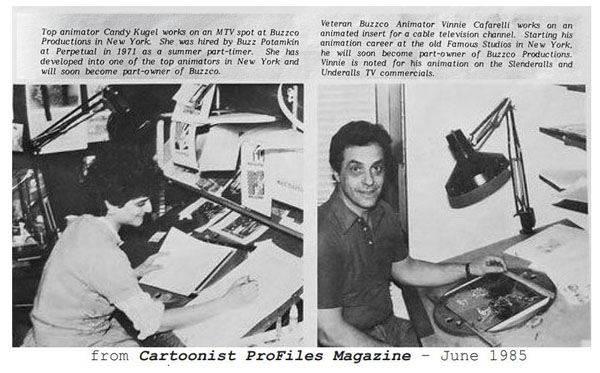

While writing the previous article about Jack Dazzo I reached out to Candy Kugel. She was, at one time, Dazzo’s boss, in tandem with Vince Cafarelli. Relevant to this story is the fact that Kugel and Cafarelli were close friends who worked together for eighteen years.

So, Candy is protective of Vince’s legacy. Respect! Producer J.J. Sedelmaier, who had worked for Kugel and Cafarelli, memorialized the guy as “a New York animation institution”. Undoubtedly, Vince Cafarelli rates wider recognition as a central figure in the New York teleblurbs industry.

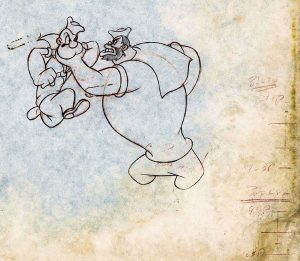

Born in the summer of 1930, Vincent Joseph Cafarelli grew up in Bensonhurst, an area known as “Brooklyn’s Little Italy”. He was the youngest of three by a dozen years, their father being a factory machinist. It was the Depression in New York City. The family got by. Right out of high school Vince started as a messenger at Famous Studios. He was soon inbetweening. That was 1948, the Depression was over, a war had been won, and things were less bleak. In 1949 Shamus Culhane returned to New York. The teleblurbs market erupted, a geyser of private sector cash raining down. Vince bid goodbye to Popeye!

By early 1951 Cafarelli was at Bill Sturm’s studio, but the Army drafted him. While in basic training, Vince married Francisca. Experiencing a bit of luck Cafarelli was stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia to do graphics for the Airborne Division. Returning home in late 1953, he took a job inbetweening for Lee Blair at Film Graphics. Working alongside Vince Cafarelli were: Howard Beckerman, just back from a combat area posting in Korea; Ed Smith, preparing to graduate from Columbia University; and Fred Mogub, who is a whole other story.

This particular batch of Assistant Animators were schooled by Disney veterans Don Towsley and Ken Walker. But I’m going to leave Vince Cafarelli there for now . . . there in 1953 . . . because this article is primarily about Jack Dazzo.

This particular batch of Assistant Animators were schooled by Disney veterans Don Towsley and Ken Walker. But I’m going to leave Vince Cafarelli there for now . . . there in 1953 . . . because this article is primarily about Jack Dazzo.

In 1953 Jack Dazzo worked for Famous Studios. I don’t know if his employment there over-lapped with Vince Cafarelli’s, or if they became acquainted later.

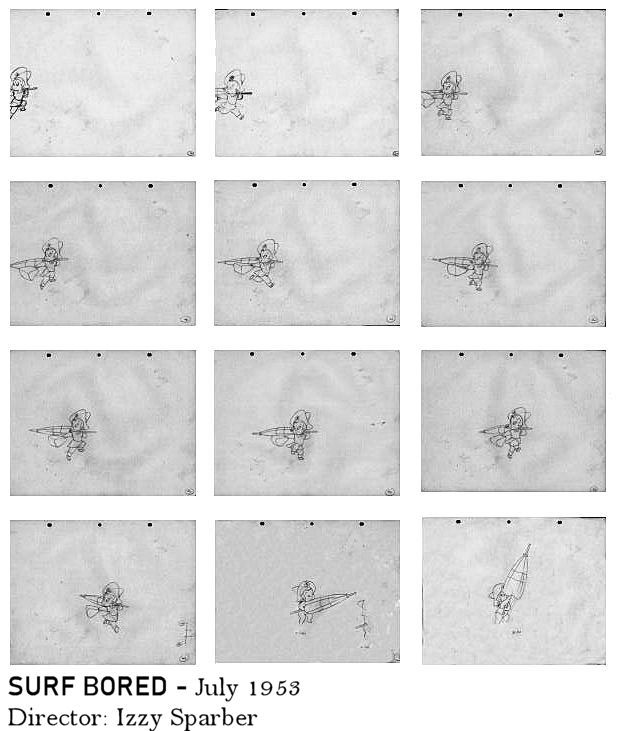

Dazzo’s nimble pencil was put to good use at Famous. His daughter Donna has very kindly allowed me access to materials Jack left behind. Among these are some work journals, but they won’t begin for another twenty years. Jack did save artwork from the early days. Below is an unused sequence from the Noveltoon SURF BORED.

Jack Dazzo fit right in with the Famous Studios crew.

Here he is a photo (below) taken in the inbetweening room by Howard Beckerman, probably in late 1950 or early 1951. Left to Right: Truman Parmalee; Lee Donahue; Connie Quirk; Jack Dazzo; Pierre DelWarde; Marcia Kaplan; Jack Willis; Lee Mishkin.

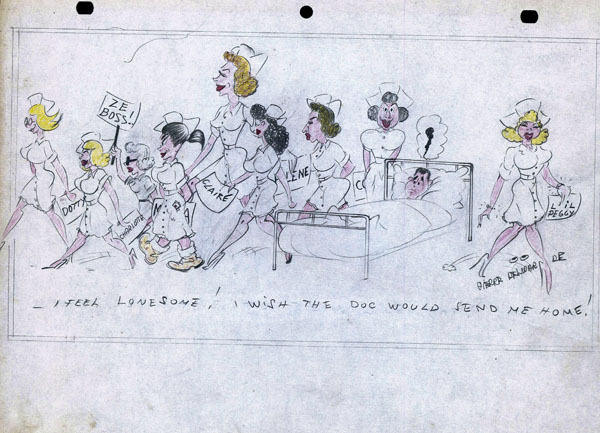

They were young, full of vim and vigor, set to go. How incredible was it that someone paid them to draw. A good chunk of extra money could be made moonlighting for teleblurb studios at night. They didn’t care about anyone’s ethnic background (though racial bias still played a role). Connie Quirk had been promoted to inbetweener at Terrytoons six years earlier because so many men were at war. She held the position when some of the men came home. Quirk held onto the job because she was good at it. Quite a few of the men in the animation business had odd views about women. Pierre DelWarde sent Dazzo the following drawing when Jack was in the hospital having a lung removed.

My guesses as to who’s who: maybe Dorothy Weber; perhaps Charlotte Lewis, Charlotte Tuggle or Charlotte Adams; “Ze Boss” is definitevly inbetweening supervisor Ruth Platt; I’m pretty sure that’s Marcia Kaplan with the boots; possibly Claire Cohen or Claire Russell; I’m supposing the tall one is Helene Spittelnick; unidentified; absolutely Connie Quirk; that last lady might be Peggy Adrian.

These inbetweeners worked under accomplished animators. Dazzo would later recall assisting: Izzy Klein and George Rufle, who’d both been around since silent cartoons; Gordon Whittier; Jim Tyre; Chuck Harriton. Surrounded by talented peers, Jack Dazzo ventured into the world of teleblurbery by joining Shamus Culhane Productions. Marcia Kaplan followed a few months later. Dazzo became a full-fledged Assistant Animator for Keith Robinson; Bob Ebeling; Rod Johnson, and Shamus Culhane himself.

Freelancing and side-jobs were a big part of the work week. Jack Daze counted Al Pross and Bill Ackerman among his mentors. Dazzo put in time on staff at Transfilm, then Elektra, under Phil Kimmelman’s direction. Lee Savage was Creative Director above them. Jack Dazzo ascended to Animation Supervisor of Elektra by 1966.

The Times Square area where Elektra was situated had gone into decline, filled with pimps, prostitutes, and drug deals. 42nd Street was a modern-day Sodom % Gomorrah. Elektra was on 46TH Street, a bit removed from the epicenter. And they were up a few floors above the maddening fray. Aside from short walks down the block for lunch at the Wentworth Hotel, or to the subway, Dazzo was mostly above it all. Dazzo was high enough up the totem pole that he could send his underlings out to run errands if need be. In 1969 Elektra relocated to Madison Avenue, barely on the East Side, which was considered cleaner and safer.

A woman named Elinor Bunin owned a studio at 151 West 50th Street. Elinor Bunin Productions specialized in tiles for theatrical films such as LILITH (1964); THE FAT SPY (1966); WAR AND PEACE (1966); THE PRODUCERS (1967); and THE ANGEL LEVINE (1970). Her company also did work with CBS, including an animated sequence for the Streisand special COLOR ME BARBRA (1966); special visual concepts for WELCOME HOME JOHNNY BRISTOL (1972); and a partly animated logo for CBS SPORTS.

Elinor Bunin earned a bachelor’s degree from New York University and a master’s from Columbia. Bunin was creative director for WNET-TV and a senior designer for CBS Television before striking out on her own. She hired animators on a freelance basis as needed because she knew little about the process. Bunin could be aloof. She’d married into copper mining money, but she always paid on time. Sometimes Elinor Bunin farmed work out to Elektra Films, forming a good working relationship with Jack Dazzo. In the latter part of 1970 Dazzo did the opening for THE GREAT AMERICAN DREAM MACHINE to run on PBS.

Elinor Bunin earned a bachelor’s degree from New York University and a master’s from Columbia. Bunin was creative director for WNET-TV and a senior designer for CBS Television before striking out on her own. She hired animators on a freelance basis as needed because she knew little about the process. Bunin could be aloof. She’d married into copper mining money, but she always paid on time. Sometimes Elinor Bunin farmed work out to Elektra Films, forming a good working relationship with Jack Dazzo. In the latter part of 1970 Dazzo did the opening for THE GREAT AMERICAN DREAM MACHINE to run on PBS.

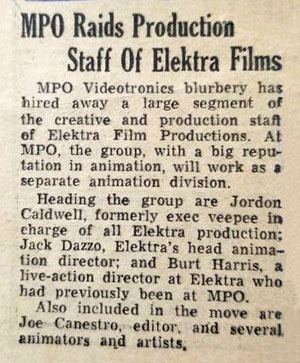

By March of 1971 Elektra Films was ready to close down. Seizing the day, a company named MPO hired key members of Elektra’s staff. MPO Productions began in 1947 at 342 Madison Avenue. The company name derived from the founders’ last initials: respected nature photographer Lawrence Madison; ad agency exec Judd Pollock; and noted editor/producer Jean Oser, who’d worked in France with Jean Renoir. Lawrence Madison was directing documentaries for the Ford Motor Company and enticed Judd Pollock away from Young & Rubicam. MPO offered ‘Complete production of films for sales promotion and training; public relations; information and training films for industry, U.S. forces and government agencies; color sportsmen’s and conservation films. Distribution service to TV stations, club groups, schools, etc.’ . . . MPO Productions was not an animation studio.

By March of 1971 Elektra Films was ready to close down. Seizing the day, a company named MPO hired key members of Elektra’s staff. MPO Productions began in 1947 at 342 Madison Avenue. The company name derived from the founders’ last initials: respected nature photographer Lawrence Madison; ad agency exec Judd Pollock; and noted editor/producer Jean Oser, who’d worked in France with Jean Renoir. Lawrence Madison was directing documentaries for the Ford Motor Company and enticed Judd Pollock away from Young & Rubicam. MPO offered ‘Complete production of films for sales promotion and training; public relations; information and training films for industry, U.S. forces and government agencies; color sportsmen’s and conservation films. Distribution service to TV stations, club groups, schools, etc.’ . . . MPO Productions was not an animation studio.

After four years MPO moved to 15 East 53rd Street, expanding into larger quarters. MPO would boast two studio production centers with lighting, photographic and sound equipment, mobile units, sound trucks, five shooting stages, make-up and dressing rooms, screening rooms, and set construction shops.

After four years MPO moved to 15 East 53rd Street, expanding into larger quarters. MPO would boast two studio production centers with lighting, photographic and sound equipment, mobile units, sound trucks, five shooting stages, make-up and dressing rooms, screening rooms, and set construction shops.

Still all geared towards live-action film. One of their divisions made a portable projector called a Videotronic, with a fold-out viewing screen for 8mm film cartridges, It was ideal for sales meetings. The TV Commercial & Industrial division became a subsidiary known as MPO-Videotronics.

Maintaining close ties with Ford Motors, MPO opened an office in Dearborn, another in Chicago, and one in Hollywood. By 1961 MPO-Videotronics presented itself as the largest producers of industrial and TV commercial films in the world. Teleblurbs accounted for 85% of their gross income. At the 2nd Annual American TV Commercials Festival, held in New York, MPO won 4 first-place awards, 2 for second-place, and 2 special citations. All for live-action stuff. Elektra Films swept the animation categories.

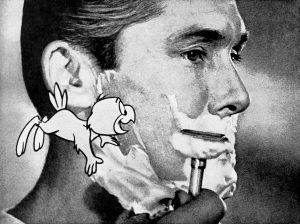

Late in 1962 MPO released a hybrid live-action/animated spot that won some praise for its animation. The client was Gillette. The product – a smooth-shaving razor. Warner Brothers Cartoon Division supplied the animation. MPO also brought genius Sol Goodnoff on board that year as Director of Special Effects. A sea-change was underway. Construction started on a new MPO Videotronics Center at 222 East 44th Street.

Late in 1962 MPO released a hybrid live-action/animated spot that won some praise for its animation. The client was Gillette. The product – a smooth-shaving razor. Warner Brothers Cartoon Division supplied the animation. MPO also brought genius Sol Goodnoff on board that year as Director of Special Effects. A sea-change was underway. Construction started on a new MPO Videotronics Center at 222 East 44th Street.

During the spring of 1963 Carlton Reiter began producing television commercials with MPO. Reiter was a partner in the animation studio Gryphon Productions with Ray Favata. When Reiter left MPO a couple months later to join the N. W. Ayers ad agency, MPO lured Lee Savage away from Elektra, which was still in its glory days at that time. Savage soon returned to Elektra.

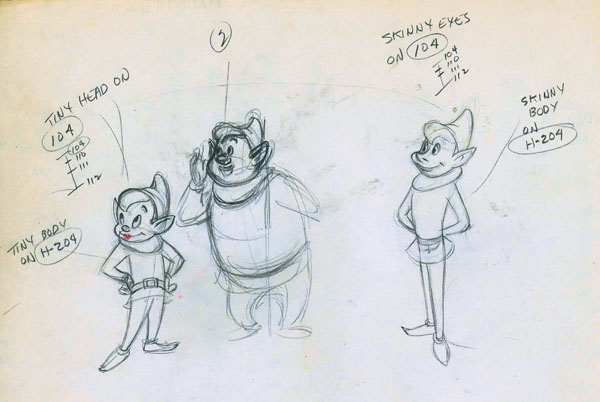

An earnest shot at animation was afoot in 1967 when MPO hired Gordon Whittier, Jack Dazzo’s old mentors. Whittier was now vice president of Screen Cartoonists’ Local 841. Three months later Keith Robinson became the new MPO animation supervisor. Robinson was an ex-Disney guy and former U.S. Marine who opened Cinemette Productions in New York with two other Leather Necks after the Second World War. He’d mentored Jack Dazzo at Shamus Culhane Productions. Robinson also had time in at Lars Calonius Productions, Transfilm, UPA, McCormack-Wade, Elektra, and Animation Central.

Peter Tytla, son of legendary animator Bill Tytla, took a job editing at MPO-Videotronics as 1968 rolled in. Peter learned the trade at his father’s studio, and also edited for Lee Blair at Television Graphics. It would be another three years before MPO smelled Elektra’s blood in the water and made their big power play. Jordan Caldwell abandoned Elektra in 1971 to run MPO’s brand new subsidiary Peridot Films. Caldwell chose the name. Peridot is a transparent yellowish-green gemstone. They would make TV ads. Jack Dazzo quit Elektra to direct Peridot’s animated commercials. Burt Harris did the same for live=action, Dazzo brought along editor Joe Canestro and cameraman Jim Seaman.

Jim Seaman had been with Lars Calonius Productions in 1959, and seems to have left to start his own shop at 45 West 45th Street. By 1962 Seaman operated a camera for Hal Seeger. Top Cel reports Seaman being at Film Formatics during 1966, but soon showed him moving over to a new company called G.D.L. that animated Bible stories. Jim Seaman joined Elektra in 1967 when cameraman Carlos Sanchez went off to found his own studio.

Dazzo and Caldwell were presented with stock in Peridot Films. Jack Dazzo now sat at the head of Paridot’s animation wing. They were a subsidiary of a subsidiary of a multi-national corporation. Whatever resources they’d need were available. Dazzo had his own office, with errand boys to pound the pavement outside. MPO provided a dining room right in their building.

With Dazzo and his crew aboard, MPO tried to recreate the elements that made Elektra great in the first place, having a poster designed by Seymour Chwast at the ultra-chic Pushpin Studios.

And things went well. While running Peridot, the prolific Dazzo collaborated with Elinor Bunin again in 1972. She’d signed a deal to provide bumpers and intersitials for the ABC Network. That’s how Dazzo came to do opening animation for THE ABC AFTERSCHOOL SPECIAL. Dazzo’s understanding with Bunin was that she would use him exclusively on any animation for ABC.

MPO turned a blind-eye when Peridot officers had something going on the side. MPO’s live-action director Dominic Rosetti went off to start Rosetti Films with Jordan Caldwell side-lining as Treasurer and Sales Manager. Caldwell prospered in that world of titles and contracts. That was around 1974, when Caldwell was also partnered with Vince Cafarelli in an animation studio called America’s Favorite.

Since we left Cafarelli two decades earlier he had been laid off when things slowed down at Film Graphics. Cafarelli took a job at Academy Pictures, immediately bonding with Pablo Ferro. Cafarelli is the one who introduced Ferro to Fred Mogub. Late in 1954 Cafarelli was an Assistant Animator for Screen Gems, the east coast satellite of Columbia Pictures. Screen Gems ceased operations by April of 1956. Cafarelli went back to Bill Sturm. A month later Cafarelli reconnected with Howard Beckerman doing lay outs at UPA. Cafarelli put in a couple solid years there until Pablo Ferro called him over to Gifford Animation in 1958.

Vince accompanied Pablo on a trip to Cuba in 1959. When they returned Pablo went to Elektra Films. A couple of years later, when Pablo formed Ferro, Mogubgub & Schwartz he brought Vince in. Cafarelli spent a good deal of 1963 criss-crossing the Atlantic Ocean while Ferro was in England working for movie director Stanley Kubrick. Those were crazy days. Vince was wing-man for the insatiable Pablo Ferro, prowling Greenwich Village’s artsy party scene, and making experimental films with Robert Downey Sr. and that indie cinema crowd. In 1964 Cafarelli became Animation Supervisor for Len Glasser’s studio Stars and Stripes Productions Forever.

Stars and Stripes Productions Forever was creative. Designer Hal Silvermintz and Production Manager Buzz Potamkin departed Stars and Stripes in 1968 to found Perpetual Motion Pictures. Cafarelli stuck with Glasser until 1974 when Stars and Stripes ended. Cafarelli paired up with Jordan Caldwell as America’s Favorite.

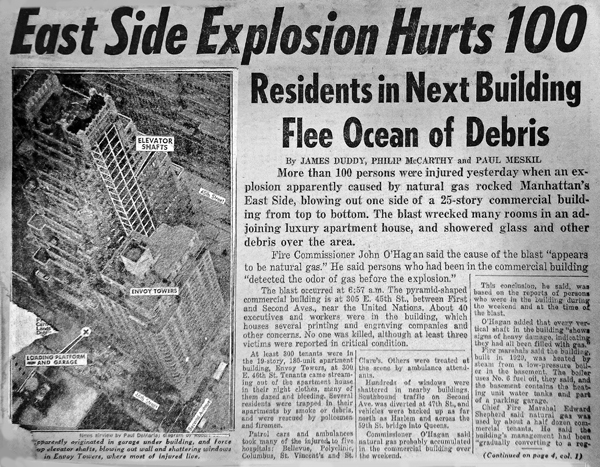

America’s Favorite. A bold concept, considering America’s instability in those days. As a U.S. President toppled, White House personnel were under indictment for conspiracy to obstruct justice, the U.S. Attorney General among them. Battle-scarred troops returned home as the Pentagon deescalated long-term involvement in the Vietnam War. We were in the midst of an energy crisis. A lot felt upside-down. Debutante heiress Patty Hearst was robbing banks with idiot terrorists who labeled themselves as revolutionaries. When an explosion rocked the East Side on April 22, 1974 speculation went wild as to the culprit.

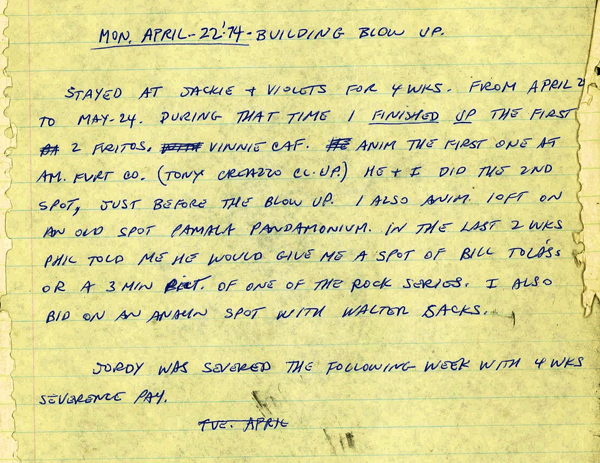

Turned out to be a furnace. But there’s a twist! According to Dazzo, they finished work on a Friday and moved the studio to a new location over the weekend. Into this building. Before anybody came in on Monday the place went Ka-Blooie! He and his crew were thrown out of a job. At this juncture Jack Dazzo returned to freelancing . . . and he started keeping a journal.

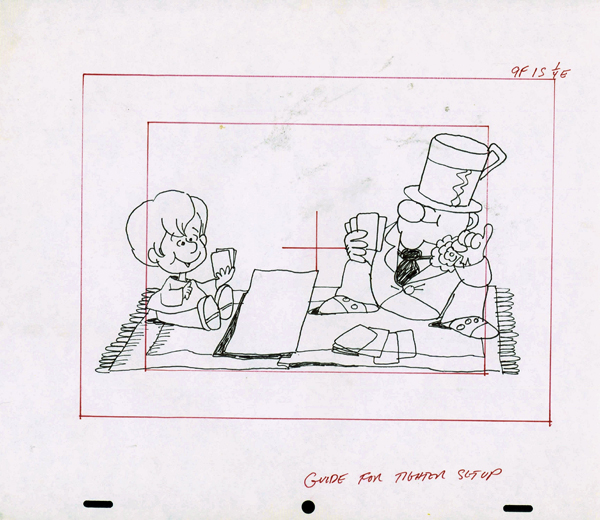

Uncompleted work from Peridot remained, specifically a couple of W.C. Fritos commercials, which brings me to the point of this narrative. Donna Dazzo posted her father’s demo reel on Youtube and we linked it to the previous article. Candy Kugel was concerned that one of the Fritos spots on the reel was also on Vince Cafarelli’s demo reel. Candy emailed me about it. She also called J.J. Sedelmaier to find out if he had any idea about the mix-up. But back then J.J. wouldn’t be on the set for another six years. Few are left who might remember. Jordan Caldwell recently passed away.

Over the phone, Candy and I settled on the caveat that Dazzo may have produced the spot at Peridot while Cafarelli might have animated it for him. There seemed to be no case of anyone improperly claiming the other’s work. Neither of them was that type of guy anyway! We also agreed that at this late date, short of someone having written it down somewhere, we’d never know.

Now that I’d finished that article I could spend some time with Jack Dazzo’s journal. That same night, the first page of the journal answered Candy’s question.

We were correct – Cafarelli worked at Peridot just before the explosion, then finished the other Fritos commercial at America’s Favorite with Tony Creazzo doing clean-up. Jordan Caldwell received severance pay from Peridot. So, what of this Violet and Jackie who supplied Dazzo a place to work?

Violet Gellman was fifty years old in 1974. Back in 1950, when Jack Dazzo went to work at Famous Studios, Violet had been inbetweening there for at least five years. She was active in unionizing the place. In 1952 Violet left the business to spend time with her two small children. She returned in 1955. She was at Transfilm in 1958 while Dazzo was there. Film Graphics snatched her up in 1960. Violet Gellman moved over to Elektra Films in 1961, where Jack Dazzo supervised animation. Jackie Bissett was with them.

A year younger than Violet, Jackie Bissett was an inker at Famous in those days when Violet inbetweened. Jackie had gone over to Ben Harrison Productions in 1948, which was before Dazzo started at Famous. Jackie worked with Lars Calonius in 1954, then at Film Graphics. In 1958 she worked for the Hubleys at Storyboard, and the next year for Joe Oriolo on FELIX THE CAT. Bissett got to know Dazzo well at Elektra in 1969 when Violet was there. Jackie and Violet joined forces, leaving Elektra to form the Ink & Paint service Cel Specialists at 18 East 41st Street, a high-rise office building near Bryant Park.

In 1974 Jackie Bissett married Clifford “Red” Augustson. This guy had been a character designer for Terrytoons in 1937, and was animating there by 1939. The Army took him into the Astoria animation unit during the war. Augustson went to Famous Studios in 1946 and married Millie Figliozzi. Who I believe was an inker. There was a Don Figliozzi animating at Terrytoons. Maybe her brother? By year’s end Augustson was at Terrytoons, while Millie went to Astoria as part of the Army Signal Corps.

Red Augustson was with Al Stahl in 1949, then with Transfilm in 1950, after which he got in at the Bill Sturm studio. 1956 found Augustson at Film Graphics working on the medical short RODNEY beside Lu Guarnier. Augustson worked on FELIX THE CAT for Joe Oriolo. In 1966 it was Bible stories at G.D.L., and the next year brought a few months in Canada alongside George Rufle. Steve Krantz put Augustson on SPIDERMAN in 1968 under Ralph Bakshi’s direction. Cineffects hired Augustson in 1970, but he was soon with Bakshi again on FRITZ THE CAT. He may have followed that production out to Hollywood, because Augustson’s next credit was for DePatie-Freleng.

In 1975 Red Augustson was at the New York Institute of Technology for the deplorable TUBBY THE TUBA movie, as was Jack Dazzo. Every freelance animator had to hustle and find jobs where they could. That explosion knocked Dazzo out of a sizeable weekly paycheck, and him with three daughters needing college tuition! He would sell his skills on the open market.

Oh, by the way, this article is titled:

Okay, so no more private office with errand boys to save him shoe-leather. No more company dining room right in the building. It was back to pounding the pavement around Times Square, which had become grittier and grimier. A month after the Peridot explosion Joe Canestro opened Sandpiper Productions, an editing service at 298 Fifth Ave. Along with Cel Specialists it would be Dazzo’s Manhattan base of operations.

Jack, Joe and Jordy Caldwell met at Sandpiper to figure out the taxes they each owed on their Peridot stock. Did it even retain any value after the studio blew up? MPO owed Dazzo severance pay and some expense account money. He and Caldwell were involved in a Right Guard Deodorant spot starring cartoonist Al Capp’s character Fearless Fosdick. Also, Dazzo waited on Phil Kimmelman to green-light him on a SCHOOLHOUSE ROCK segment . . . something about a piece of legislation singing the blues on the Capitol Building steps.

For lunch on May 24th, 1974 Jack Dazzo met Marvin Friedman at Cel Specialists. Marvin Friedman had been a Designer and Lay Out Artist at UPA during the Fifties. When Roger Wade Productions started an animation department in 1959 Friedman ran it. He was also Vice President in charge of Animation at Wylde Studios during the Sixties. Now, Friedman seemed to be working with the ad agencies. Dazzo bid on four commercials. . .

(to be continued)

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

Fascinating stuff –

A dizzying rollercoaster ride of an article.

There is more information here than in some books in recent years about animation history.

Your research is much appreciated.

I was very interested to see Jean Oser’s name mentioned as one of the founders of MPO. About six years ago I wrote an article about the 1927 Dadaist short film “Vormittagsspuk”, which Oser edited and also appeared in as an actor. The film uses stop-motion and cutout animation as well as live action, so Oser, who was only nineteen, was really plumbing some uncharted territory in filmmaking. The film is known in English as “Ghosts Before Breakfast”, but a more accurate translation of the title would be “A Forenoon’s Spook”; in the German slang of the 1920s, the word “spook” meant a wild and crazy adventure or entertainment. Director Hans Richter chose the title because the filming was completed in a single morning; the editing took longer.

Oser was half-Jewish and moved to Paris after the Nazi Party came to power in Germany. While there, among other things, he translated the new American blockbuster “King Kong” into French and also reedited it. (He cut the scene where Fay Wray steals an apple because he thought that made the character unsympathetic, but he later regretted that decision.) After serving in the French Foreign Legion, he came to New York in 1942 and was promptly drafted into the U. S. Army Signal Corps. His short film “Light in the Window” won the Academy Award for Best Short Subject in 1953. In 1970 he moved from New York to Saskatchewan to help establish the Department of Film at the University of Regina. He died there in 2002 at the age of 94.

Was Jackie Bissett the artist any relation to Jacqueline Bissett the actress?

Why isn’t there more literature about Famous Studios, since it seems that its history is more interesting than most of its cartoons? Particularly the way it splintered off into so many other animation entities, with several Famous veterans doing more creative work elsewhere.

There’s a book about the history of their comics licensors (and later owners of the studio’s characters), Harvey by Mark Arnold:

https://www.amazon.com/Harvey-Comics-Companion-Mark-Arnold/dp/1629331732/ref=asc_df_1629331732/?tag=hyprod-20&linkCode=df0&hvadid=312126478490&hvpos=&hvnetw=g&hvrand=17898253801458791968&hvpone=&hvptwo=&hvqmt=&hvdev=c&hvdvcmdl=&hvlocint=&hvlocphy=9014901&hvtargid=pla-466378419761&psc=1&mcid=9fa369fe594e3c30a4ccc6a3af5d6302&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIpPzuseKXhAMV42hHAR1GWwq1EAQYASABEgI35fD_BwE

There’s also a docuseries of the comic company that still doesn’t have a release date.

Thank you for mentioning Vinny! A few corrections: (Relevant to this story is the fact that Kugel and Cafarelli were close friends who worked together for eighteen years.) Kugel and Cafarelli were partners at Buzzco Associates from 1985 until Vince’s death in December 2011. Having met at Perpetual Motion Pictures, they worked together for 38 years.

then (Born in the summer of 1930, Vincent Joseph Cafarelli grew up in Bensonhurst, an area known as “Brooklyn’s Little Italy”. He was the youngest of three by a dozen years, their father being a factory machinist. )

He was the youngest of FOUR and his father was a barber who owned a shop in Coney Island.

I can’t comment on his career before I met him at Perpetual Motion Pictures the summer of 1974.

Very interesting article, with so many details!

However MPO Videotronics was founded by Madison Pollack and O’Hare, not Oser.

The VP then later President was Arnold Kaiser.

I worked at MPO when I was very young.

It was a huge and fascinating company when it was at its biggest location at 222 E 44th st. 1960’s – the mid1970’s.

The main focus became live action commercials, with a developing animation dept. as mentioned.

An amazing mix of talent worked there and the stellar alumni went on to work in features films, as well as independent production companies.

Live action filmmakers and Producers included, Mike Cimino, Gordon Willis, Owen Roizman, Dominic Rossetti, Marshall Stone, Jerry Hirshfeld, Harold Friedman, and so many more!

I also remember Joe Canestro the Editor very well and his affiliated company, Sandpiper.

Here’s another article I found, https://www.filmkorn.org/super8data/database/manufacturers_list/m_/mpo.htm

Thank you. I stand corrected. I will research Paul O’Hare.

If you want to be interviewd contact me through Jerry.