Suspended Animation #316

F. Maurice Speed, a British film critic, contacted Walt Disney to write about Disney’s latest animated feature film for his 1948-1949 annual volume about films. Speed was a British film critic who decided that “What the ordinary moviegoer lacks is a more or less complete annual record, in picture and story, of his year’s filmgoing.”

So, in 1944, he created the book Film Review for primarily U.K. film fans, which still continued on after his death in 1998. The book was not just composed of reviews but short articles, celebrity profiles and more all related to film.

So, in 1944, he created the book Film Review for primarily U.K. film fans, which still continued on after his death in 1998. The book was not just composed of reviews but short articles, celebrity profiles and more all related to film.

Many articles in magazines and books, like this one, featured the byline of Walt and it is doubtful whether Walt himself actually wrote most of them. However, he did have to approve anything that went out under his name that it reflected his perspective about the topic, even if it was crafted by Joe Reddy and his publicity department at the Disney Studio.

Often, they would use Walt’s actual words but formatted in a more formal context.

James Bacon, a columnist for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, wrote frequently about Disneyland and said, “I once asked Eddie Meck, Disneyland’s longtime publicity director, what made Disneyland the greatest man-made tourist attraction of all time. I fully expected him to give me a long spiel. Instead, he said: ‘I can give it to you in two words: Walt Disney. We don’t even mail a postcard out of here without his OK’.”

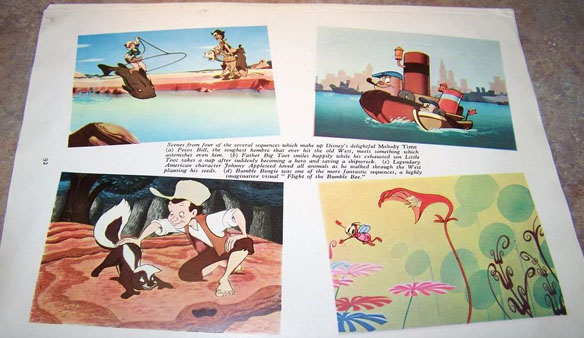

A page from the “Film Review” spread on “Melody Time”

Here is that essay from that volume of Film Review on Walt’s thoughts about the compilation films:

As this particular section of Film Review goes to press (and, rather unfortunately in the circumstances, it happens to be one of the earliest) neither Walt Disney nor distributors R.K.O. Radio have any idea whether the maestro’s only new full-length effort “Melody Time”, is likely to be released, or even premiered, in England his year, or whether we shall have to wait until early 1949 to see it.

Some Facts About Melody Time by Walt DisneyIn any case, no stills or pictorial matter of any kind are available at this moment to give you a preview of the kind of picture it is. So I thought, in the circumstances, the only alternative—other than ignoring an important cinematic event—was to ask Disney to himself describe his production. And this is what he has done for you on this page. Should later news come in about the release of “Melody Time” before the last section of this volume goes to press. I shall give in somewhere in the Stop Press pages at the end. — The Editor

An important period in the history of Disney product will be marked by the release of our new feature-length fantasy Melody Time, and, since it may seem to signalize a departure from such productions as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Pinocchio, Dumbo and Bambi and other similar features already announced for our forthcoming program, our new film musical prompts an explanation as to its origin and technique.

In the first place I want to stress that the multiple-episode cartoon fantasy will not replace the classic fable picture on the Disney schedule. From our standpoint the Melody Time formula is as essentially “Disney” as any other kind of screen entertainment associated with our name, the one type merely offering a change of pace from the other, and keeping our products from crystallizing around a set specification.

The literary archives of the world are filled with screenable riches, with tale and anecdote, fable and fantastic folklore. Wonderfully amusing and dramatically potent, they are often so concentrated in form as to be entirely unsuited for feature-length film treatment.

After the war, when once again we could think about entertainment films, we had in mind a number of these titles such as “Peter and the Wolf” and “The Whale Who Wanted to Sing at the Met” which we were eager to make, but which didn’t seem to fit into the usual screen pattern. Urged on by the times and circumstances we decided to assemble several of these in a novel presentation, and Make Mine Music, the finished product of our initial experiment, showed us we had discovered something very important for our bill of fare.

By all the evidence we were convinced that we had enlisted a new segment of habitual movie-goers, and we now know that the variety of important names from screen, radio and the realms of music who have enthusiastically adapted their gifts to our cartoons have proved a definite asset in enlarging our younger audience.

We followed up with Fun and Fancy Free, a combination of two distinct tales, and our latest feature along these lines has seven episodes woven around the core of American mythology.

Take, for example, the legendary figures of Pecos Bill, tall-tale hero of the cowboys, and Johnny Appleseed, the more modest but nevertheless colorful frontiersman, central characters in Melody Time. These two mighty men of folklore are a compound of anecdotes and prodigious deeds, but neither of them has more than the most sketchy “life story” with which to occupy the full seventy minutes of the feature picture.

Yet, by letting them share time and honors with other cartoon performers, together with the living actors who sing and speak through the animations, we are able to keep them vividly alive for all kinds of audiences each and every moment they are on the screen.

On the basis of advance tests and polls for this our “myth-musical” we are confidently proceeding with another combinations of fantasy in Two Fabulous Characters, wherein Ichabod Crane from The Legend of Sleepy Hollow will cavort with Mr. Toad from Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows.

Again, I want to emphasize that the effective use of material otherwise denied to the motion picture is what appeals to me chiefly in making the kind of entertainment represented by Melody Time.

Ordinarily, changes in form and material come slowly in popular diversion, this applying to screen and stage alike, but occasionally there are circumstances which dictate swift innovation, and then we discover, to our amazement, that the public has been ready and waiting for some recipe we have been too timid to propose.

It pleases and encourages me to learn that ‘Disney’ style is not so fixed and limited in the public mind as to preclude further exploration in the field of entertainment.

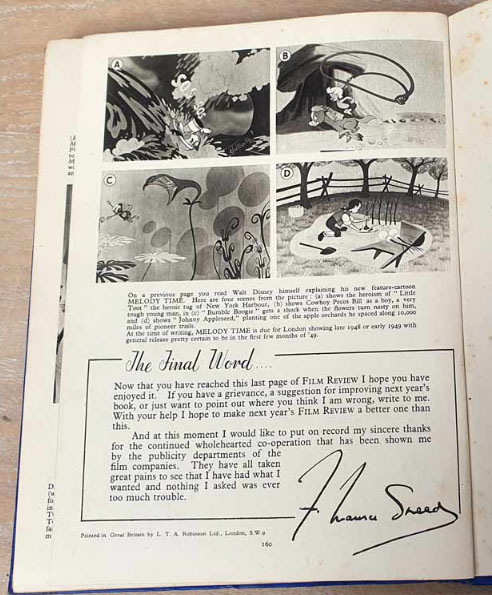

The final page of the 1948 FILM REVIEW

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

It’s interesting to note that the reasons given here to justify the release of the package features are not budgetary constraints, wartime restrictions, the closing of the European market, or a reduction in the labor force due to conscriptions, but simply that the stories under consideration did not warrant full-time feature treatment. It is the demands of the stories themselves intrinsically rather than external factors which are provided as the reason behind the shift from longer fare to shorter.

This reads like cleverly-worded publicity, and was probably not written by Disney himself, although very likely it was approved by him, as it does not disparage the Disney product in any way but explains the latest developments as new and fresh approaches to entertainment.

I appreciate the opportunity to read something I have never read before regarding this fascinating era in the history of the Disney Studio. The package features tend to be treated with a degree of condescension or contempt by viewers and critics, and this has always seemed to me as an unfair assessment–not taking into account the remarkable flexibility (to say nothing of versatility) that is demonstrated in these films. They may not be the pinnacle of the Disney output, but would anyone really prefer that they had never been made?

Wow Jim, this is golden. In a presentation, Randy Thornton also played rare audio of Walt speaking along the same lines about the package features–as to how the length of each segment was dictated by the story first and foremost so it was always a creative consideration–but this is the most richly detailed statement yet.

What it illustrates is one of the most powerful reasons why there was and still is a “Walt Disney.” He and his people were able to establish a public mindset of what “Disney quality” meant, his commitment to it, and how each of his productions met that standard no matter how humble it was. You will notice that there is no denying of “circumstances,” it really is an honest statement but always pointed toward making the finest entertainment under any circumstance.

In doing so, the public will be very forgiving, knowing that you deliver the goods so often that even when some things are not perhaps as good as others when placed side-by-side. You can also note Walt personally acknowledging reaching toward a younger audience, particularly teens, by utilizing pop artists of the day. When people ask me about current pop artists in Disney projects, I always point to the tradition set forth here. It ain’t new.

I love the package films, particularly the musical ones. They are not the full-story features, they cannot be. But they offer a breadth of variety and richness that one theme cannot. There were no TV half-hour specials in the 1940s and not much in the way of two-reel animation save for the classic Fleischer Technicolor Popeyes. I’m so glad they exist.

i loved”melody time”when i saw it years ago on the disney channel.if it’s still available,i want the DVD!

Neat post. Get the European DVD of MELODY TIME as it is uncut, uncensored and complete. The American version is not worth having. Get an all regions Blu-ray player as they play all DVDS. I have both versions. Ditto MAKE MINE MUSIC. https://www.amazon.co.uk/s?crid=2EGN01DRK62PX&i=aps&k=disney%20classic%20dvd%20melody%20time&ref=nb_sb_ss_ts-doa-p_1_22&sprefix=melody%20time%20DVD%20disney%2Caps%2C240&url=search-alias%3Daps

Whoever wrote that article “in his own words” must have self-consciously decided to purple up his prose for the British press. It’s impossible to imagine such florid polysyllabic locutions being uttered by Walt Disney. But I can imagine him looking over the copy and saying: “I had no idea I could write so well!”

“…[T]he multi-episode cartoon fantasy will not replace the classic fable picture on the Disney schedule.” By this time, of course, “Cinderella” was already a work in progress, so in a way this promise had already been kept. But if it had been a commercial disappointment, or only a modest success, might Disney have gone back to making package features? Hmmm….

The article has very little to say about “Melody Time” itself. It’s more of an apologia defending the package film format per se. A compelling argument that Disney or his amanuensis failed to make comes from the realm of literature. At the time the package films were made, many magazines printed short fiction; assemblages of short stories of different lengths, in different styles and by different authors could be found packaged together within the same covers on any newsstand. Often these stories were later published in book form as collections by the same author, or anthologies by various ones (e.g., The Best of Esquire 1950). My parents owned many such books, and I checked out many others from the public library when I was growing up. A lot of authors preferred writing short stories to novels, because they actually paid better. So I think the question should be, not why did Disney make package films, but why didn’t others do so?

This is especially vexing when it comes to musical films, for concert programs (to borrow another metaphor) assemble a number of separate works into a single “package”. The Disney package films seem to have influenced Gene Kelly’s “Invitation to the Dance”; Gene and Walt were personal friends, and some of Disney’s technicians assisted the Hanna-Barbera unit with the technology of combining animation with live action in the Arabian Nights segment. I’m convinced it could have been a hit if MGM hadn’t gotten skittish, delayed its release and confined it to the art houses.

In the seventies there were some wildly successful comedy anthology films like “The Groove Tube”, “The Kentucky Fried Movie” and Woody Allen’s “Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (But Were Afraid to Ask)”. There have also been successful horror anthologies, like the “Creepshow” and “Tales from the Crypt” series as well as others from Roger Corman and Hammer Films (with apologies to Mr. King, the horror genre is better suited to the short story than to the novel). In animation there were “Heavy Metal”, “Allegro Non Troppo”, “Neo Tokyo” and Disney’s own “Fantasia 2000”.

Alas, the short story as a literary form has gone the way of the cartoon short subject: they still get made, but they have little commercial viability. But I can still enjoy rereading my collections of Edgar Allan Poe, James Thurber and P. G. Wodehouse, just as I can enjoy watching “Melody Time” for the umpteenth time, any time.

Another reason for the package films was to preserve and expand the Disney brand in feature films. Disney knew he couldn’t survive on shorts alone, especially as the competition was catching up and even surpassing Mickey and the gang in popularity while double features were beginning to squeeze out cartoons altogether. And every traditional animated feature was a huge roll of the dice. So the studio got into live action, building on the kiddie fare reputation of the cartoons with emphatically family-friendly (and often thrifty) movies.

It’s important to remember that for all his visibility Walt Disney was a minor player among the Hollywood moguls. When the majors were cashing in on 30s-40s “habitual moviegoers” with a massive output of As and programmers, Disney was selling single-reel shorts with a feature every few years. For distribution he was dependent on a succession of big studios, who’d use Mickey to prop up their own product. That business model wouldn’t hold, especially when the end of the war meant the end of those lifesaving government contracts.

In the postwar years the package films allowed Disney to offer a new title every year, keeping up his image as THE producer of animated features and supplementing the initial trickle of live action. And as noted, further cementing the Disney brand as family entertainment. No other studio was targeting all its output to a specific demographic, especially that one. To compete with television many were stressing “adult” themes. So parents embraced the Disney name as a guarantee of a safe show, giving Uncle Walt a near-monopoly on baby boomers. (When those boomer babies reached puberty, American International successfully claimed them with targeted drive-in fare. But that’s another story.)

In time Disney not only had a full schedule of live action features to sell, but enough years had passed to reissue the prewar animated features between the new ones. His studio was still not the biggest, but the only one with such a clear public identity. And with merchandising and theme parks, movies became just a slice of a larger pie.

The package films had served their purpose. There would still be featurettes — originals as well as excerpts from the package films — attached to theatrical features and deployed on the television show. But with the very qualified exception of “Fantasia 2000”, they were over.

Anybody still reading this?