Suspended Animation #271

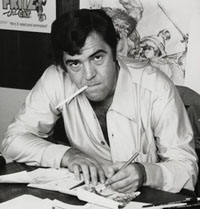

Because I was writing a continuing column on animation for The Comics Journal magazine, I had an opportunity to interview director Ralph Bakshi at his studio just before the release of his animated version of The Lord of the Rings (1978) for an article that was supposed to promote the feature.

I recently stumbled across my notes from that old interview. As usual, I’ve eliminated my questions because I think you can get the gist of them from Bakshi’s responses.

I recently stumbled across my notes from that old interview. As usual, I’ve eliminated my questions because I think you can get the gist of them from Bakshi’s responses.

Ralph Bakshi’s rise in animation had been phenomenal at that point. Immediately after graduation from the High School of Industrial Arts in Manhattan, Bakshi began working for CBS Terrytoons. Starting as an inker, he was quickly promoted to becoming the youngest animator on staff, then the youngest director and finally the youngest studio director. He was running Terrytoons at the age of 26 when he came across LOTR.

The film rights for LOTR were held by Walt Disney for ten years, eventually passed to United Artists in 1968 where both Stanley Kubrick and John Boorman failed in their respective attempts to put together a workable screenplay. Bakshi began making annual trips to United Artists to find out when the film rights would be available.

Bakshi: “In 1956, the Tolkien books were given to me by a director at Terryoons to read. In 1957, I started trying to convince people that the books could be animated and tried to obtain the rights but I was told that Disney had them.

Wizards (1977) was a comic book for a young audience. It was Sword and Sorcery for kids. People accused the film of shortcutting but I really loved it. I felt Mike Ploog’s drawings in the beginning were terrific. It was like comic books. I love comic books. I loved that sequence. We also used the rotoscope in Wizards but we didn’t have the time to put in the detail like we did in LOTR.

Wizards (1977) was a comic book for a young audience. It was Sword and Sorcery for kids. People accused the film of shortcutting but I really loved it. I felt Mike Ploog’s drawings in the beginning were terrific. It was like comic books. I love comic books. I loved that sequence. We also used the rotoscope in Wizards but we didn’t have the time to put in the detail like we did in LOTR.

“I was told that at Disney the actor was told to play it like a cartoon with all that exaggeration. In LOTR, I had the actors play it straight. The rotoscope in the past has been used in scenes and then exaggerated. The action becomes cartoony. The question then comes up that if you’re not going to be cartoony, why animate? I think it’s the same reason Howard Pyle illustrated. Why illustrate? Why not just take a photograph? The reason is that there is an energy there and that’s important.

“In LOTR, it is the traditional method of rotoscoping but the approach is untraditional. It’s a rotoscope realism unlike anything that’s been seen. It really is a unique thing for animation. The number of characters moving in a scene is staggering. In LOTR, you have hundreds of people in the scene. We have cels with a thousand people on them. It was so complex sometimes we’d only get one cel a week from an artist. It turned out that the simple shots were the ones that only had four people in them.

“I didn’t start thinking about shooting the film totally in live action until I saw it really start to work so well. I learned lots of things about the process, like rippling. One scene, some figures were standing on a hill and a big gust of wind came up and the shadows moved back and forth on the clothes and it was unbelievable in animation. I don’t think I could get the feeling of cold on the screen without showing snow or an icicle on some guy’s nose. The characters have weight and they move correctly.

“What was I trying to do? I wanted to bring another level to animation. I wanted to try to get away from the Wizards cartoon work. The goal was to bring as much quality as possible to the work. I wanted real illustration as opposed to cartoons. I visited Tolkien’s daughter and his executor and a biographer in England. I spent time in Oxford to find out what her father thought. Of course, things had to be left out but nothing in the story was really altered. Tom Bombadil was dropped because he didn’t move the story along. Descriptions were dropped because you actually see it in the film.

“It’s not that important to me how a hobbit looks. Everyone has their own idea of what the characters look like. It’s important to me that the energy of Tolkien survives. It’s important that the quality of animation matches the quality of Tolkien. Who cares how big Gandalf’s nose is? The tendency of animation is just to worry about the drawing. If the movie works, whether you agree about Bilbo’s face or not, the rest becomes inconsequential.

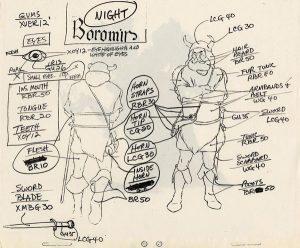

“No contemporary illustrators inspired me on this film. The major influence was guys like Pyle and Wyeth. It’s very classical. Actually, the film is a clash of a lot of styles like in all my films. I like moody backgrounds. I like drama. I like a lot of saturated color. Of course, a big problem was controlling the artists so they drew alike. How do you have 600 people draw one character alike? The tendency is to want to let the artist have some freedom but then someone would leave off a hat or horn on a hat on a character.

“No contemporary illustrators inspired me on this film. The major influence was guys like Pyle and Wyeth. It’s very classical. Actually, the film is a clash of a lot of styles like in all my films. I like moody backgrounds. I like drama. I like a lot of saturated color. Of course, a big problem was controlling the artists so they drew alike. How do you have 600 people draw one character alike? The tendency is to want to let the artist have some freedom but then someone would leave off a hat or horn on a hat on a character.

“The only joy you get during the year is seeing the background paintings. Johnny Vita has painted the backgrounds on all my films. He’s about 65. He does 15-20 paintings a day. He’s worked for me for seven years. I met him at Terrytoons. He paints better than Frazetta and Jones.

“Making two pictures in two years is crazy. (The live action reference and the actual animated feature.) Most directors when they finish editing, they are finished; we were just starting. I got more than I expected. The crew is young. The crew loves it. If the crew loves it, it’s usually a great sign. They aren’t older animators trying to snow me for jobs next year.

“I love the medium very much and when it starts to work, it’s fantastic. I’m now interested in building an animation company and I’m certainly amazed at the belief these younger guys had in me that we could do it. I think we’ve achieved real illustration as opposed to cartoons.

“The directorial problem was directing an epic. Epics tend to drag. The biggest challenge was to be true to the book. LOTR was done with honesty. You can’t buy the love that went into the project. It’s the finest thing I’ve done. It probably could be the highlight of my life. I spent two years with Tolkien and there’s nothing wrong with that.”

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Kodaliths beyond Imagination!

So how did the rights broke down? I mean there’s also that Hobbit curio that Gene Deitch did in the middle ’60s.

Bakshi’s Lord of the Rings is a flawed but valiant effort to adapt Tolkien’s massive narrative. At its best it does manage to at least capture the flavor of the text, but the rough-and-ready approach typical of Ralph’s work, while apt for his early gritty urban satires, does the high fantasy epic no favors. The choice to use rotoscoping and Kodalith transfers is sound economically, and makes for some striking imagery, but it also makes it too earthbound. Galadriel being tempted by the Ring should have been harrowing, as it was in the Peter Jackson version; instead, she comes off as a hippie chick rejecting a friendship bracelet. The appearance of the Balrog is a particular disappointment; it is quite literally a guy in a cheap costume. An animator like Bill Tytla or Ray Harryhausen could have done justice to one of fantasy literature’s greatest creations, but sadly that was beyond Bakshi’s resources.

THE LORD OF THE RINGS is my favorite book, and the Bakshi version always looked atrocious to me, so aside from a few clips, I’ve never seenit, and never wanted to. (For what it may be worth, I don’t like the Peter Jackson films either ). After reading this piece, I thought maybe I should watch it, and with the trailer right here handy, figured I’d at least watch THAT. Having done so, I’ll not make myself endure any more of it. IYIYI. All that high-minded discussion about a film that looks and feels like a Filmation production…