Born November 25, 1911, Paul Murry joined the Disney Studios in 1938 and was an assistant animator to the legendary Fred Moore on Pinocchio.

Murry became a full animator on Dumbo and worked on Fantasia (where he did some work on the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” sequence), Saludos Amigos, Song of the South, some Mickey Mouse shorts (like The Pointer 1939), as well as other projects (like 1946’s The ABC of Hand Tools), although his name never appeared on screen.

Murry got his start in newspaper cartooning by doing strips for Disney based on Jose Carioca and later Panchito from The Three Caballeros. From October 14th, 1945, through July 1946, Murry penciled the “Uncle Remus” comic strip. It was Murry’s work on this strip that offered his first opportunity to do comic book work when he provided an Uncle Remus story for Dell Four Color #129.

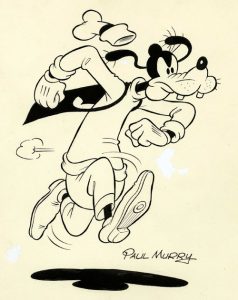

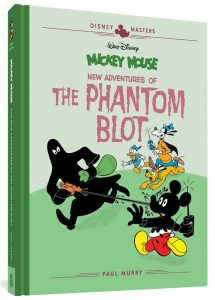

He quit the Disney Studio in 1946 and began doing freelance work for Disney-related comic books, in particular stories featuring Mickey Mouse, since Murry had been assistant to Fred Moore, considered the expert on the Mouse. Perhaps Murry is best known for doing the artwork on many of the Mickey Mouse serial adventures in the back of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories comic book for many years.

He quit the Disney Studio in 1946 and began doing freelance work for Disney-related comic books, in particular stories featuring Mickey Mouse, since Murry had been assistant to Fred Moore, considered the expert on the Mouse. Perhaps Murry is best known for doing the artwork on many of the Mickey Mouse serial adventures in the back of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories comic book for many years.

Murry died on August 4, 1989 at his home in Palmdale, Calif. He was survived by 29 grandchildren.

In the late 1960s, I met through correspondence another comics fan named Wayne DeWald. One of the things he shared with his fellow comic friends was a letter he received from Murry.

DeWald, who lived in Florida at the time, wanted to do a series of profiles on animation and comic book artists and wrote to them in hopes of getting a response that he could use in his apazine for CAPA-Alpha called “Therefore.” The membership of that apa was less than 50 members, so very few people ever saw DeWald’s work.

When I re-discovered some of my old copies of K-a, I contacted DeWald for permission to reprint the letter.

Wayne told me, “(Murry) was one heck of a nice guy and we exchanged several letters—none of which I still have unfortunately. The letters were lost as the result of several cross-country moves: Florida-Utah-Florida-Texas (Houston to Dallas). I am certain they will never resurface. To the best of my recollection I think we were in touch about 1968-1970.

“He seemed to have really enjoyed his time in animation. We mostly talked about animation. Besides the correspondence, I may even have spoken with him on the phone as I recall.

“I’m not sure why we stopped corresponding. It seems to me that about this time I was going through a lot of changes—like getting married, etc.—so I may have dropped the ball at some point. It certainly wasn’t a case of him being unhappy or anything. He was very cordial. In those days I regularly wrote letters to just about every artist I could think of like Don Martin and Hal Foster, usually getting at least a note in response.”

Here is the content of that entire surviving letter:

Murry: The Studios in ’38 were located in east Hollywood on Hyperion Avenue near the Hyperion Bridge leading to Glendale. It was a simple strung out set up built in Old Spanish style. It included quite a few small residential houses in the neighborhood added to it due to needed expansion. Imagine an office complete with kitchen, bedrooms, dining room, bath, etc.

“Sounds modern but was anything but that. I had a friend at the time working on the old ‘Felix the Cat’ comic strip who had one whole house to himself. May sound good but was pretty lonesome. You can imagine during the hot summers, trying to work without air conditioning.

“Sounds modern but was anything but that. I had a friend at the time working on the old ‘Felix the Cat’ comic strip who had one whole house to himself. May sound good but was pretty lonesome. You can imagine during the hot summers, trying to work without air conditioning.

“I was always located in the main building. The furniture was simple and cheaply built. The drawing desks were made by some carpenter of soft wood and painted orange and yellow. They were covered with carved initials and cigarette burns. We sat in old straight back kitchen type chairs—pretty hard on the human posterior even with cushions stacked on them. Everyone was happy though and it actually was a paradise compared with other places. The freedom we had was almost unbelievable.

“We were given three days a week sick leave with full pay and no questions asked. If we were out more than three days during a week, we were then checked by the studio nurse and, if legitimate, our pay continued. As you can see it was a good way to weed out the dead wood. We could pick up the phone and order anything to eat or drink (not alcoholic) we wanted and it would be delivered to our rooms. Some kept small refrigerators. We came and went from the Studios as we pleased.

“There were no time clocks, no signing in or out. What if you were a couple hours late to work or left a couple hours too soon? The freedom seemed to be unlimited. And again, this would show up the dead wood. The result was the Disney Studios had the best talent in the industry. Of course, there were those who consistently abused these privileges and did not work and were released.

“My first encounter with Walt Disney himself will always stick in my memory. It amuses me now but then—not so! I had only been there a few months but was lucky enough to have the top animator, Fred Moore, take me under his wing. Fred and his unit always had a beer break at 3 o’clock every afternoon. Me, being the newcomer, had to collect the money from each one and go through the front gate over to Ma Applebaum’s drug store directly across the street and buy the beer; then, bring it back to the Studio.

“After we drank it, I had to make the return trip back to return the empty bottles, which was also getting rid of the evidence.

“This had been going on for weeks without repercussions. Came the day when I was walking out the front gate loaded down with empty beer bottles. There stood Walt, talking with someone else. He looked me over as I walked by, but said nothing and I wasn’t about to say anything. I stalled around in the drug store, hoping he wouldn’t be there on my return trip. He was still there—never mentioning the beer bottles.

“I was a bit uneasy not knowing what the results of that encounter would be. I immediately told Fred Moore what had happened and he said not to worry about it. A few minutes later he received a phone call from Walt asking Fred to come up to his office for a little talk. I heard no more about the incident, but needless to say, there were no more afternoon beer breaks.

“We played as much as we worked, but when we did work we turned out a superior product which was what Walt wanted. It was during this period that Ward Kimball organized his now-popular band The Firehouse Five Plus Two. Their practicing could be heard all over the studio during business hours and their sounds weren’t always pleasurable to the ears. Such goings on spread discontent among those who didn’t believe in such and those who were just plain jealous. Sooner of later unionism was inevitable. It produced a sort of class system—those who couldn’t play and get away with it and those who could.”

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

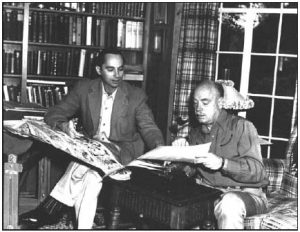

Dick Huemer is the spitting image of Bill Walsh.in that photograph.

It’s great that you were able to preserve the text of Paul Murry’s letter to Wayne DeWald now that the original is gone. So much information about the early animation studios has disappeared down the memory hole. I’m reminded of a letter by Rembrandt that was discovered in the 19th century, translated into Italian, published in a book and subsequently lost. We’re lucky to have even that translated text, but unfortunately it has nothing to say about Rembrandt’s life and art — just complaints about money owed to him.

Especially interesting that the Firehouse Five Plus Two was not as universally popular with the Disney staff as its later appearances on the Disneyland show seem to imply.

“The Fitsy-Fotsy-Figgaloo Fishes” — now that’s a cartoon I would definitely watch.

This was an interesting read. For some reason, reading the story about the beer breaks made me imagine a Paul Murry-style Mickey Mouse nervously looking over his shoulder while carrying bottles.

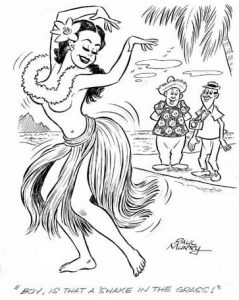

Murry did several hundred of those girlie cartoons but usually not for Humorama but other publishers.. Quite often the characters look a lot like folks for the Mickey Mouse comic stories!

My uncle lived next door to Paul Murry in the 1960’s, and Paul gave me three of his discarded drawings, which I eventually had framed (one sheer large drawing of Brer Rabbit, and two drawings of Mickey and Goofy that look like they were for a comic book). How would I determine their worth?