John Hench (June 29, 1908 – February 5, 2004) is best remembered these days for his Imagineering design work on the Disney theme parks, especially their use of color. He was a well respected mentor at Imagineering.

However, he began his remarkable 65 year with Disney in May 1939 when he was assigned as a story artist, layout and background painter to the animated feature Fantasia (1940). His work on Disney animation is often forgotten when he is discussed and his contribution to Fantasia has not really been documented – even in the book he wrote himself.

However, he began his remarkable 65 year with Disney in May 1939 when he was assigned as a story artist, layout and background painter to the animated feature Fantasia (1940). His work on Disney animation is often forgotten when he is discussed and his contribution to Fantasia has not really been documented – even in the book he wrote himself.

In 1990, Fantasia was celebrating its 50th anniversary and I was invited, as I sometimes was because of my writing on animation, to Imagineering to hear an informal conversation with Hench as he shared some of his memories of working on the film.

These type of interesting talks happened all the time at Disney and it has always bothered me that they were never shared outside that small group with the general public or historians who would appreciate them. Here is my transcription of part of Hench’s talk.

John Hench: I was in this crowded apartment connected to the studio. I was surrounded by incredibly talented people. Everybody was experimenting with pastels on black paper so I took that up too.

John Hench: I was in this crowded apartment connected to the studio. I was surrounded by incredibly talented people. Everybody was experimenting with pastels on black paper so I took that up too.

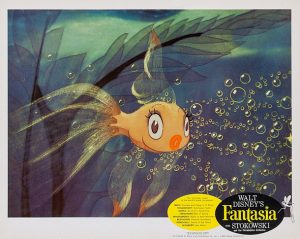

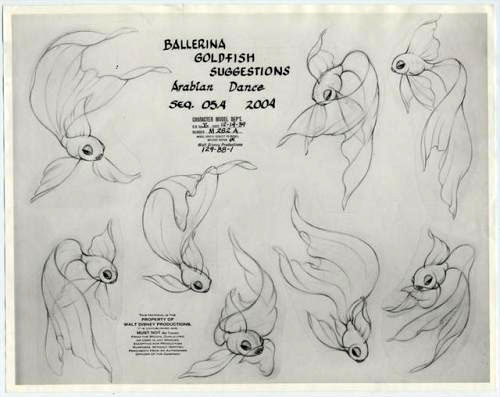

When I got there, they were having a problem making the Arabian Dance section of The Nutcracker Suite work. When they found out I could draw sexy girls, they told me to take a stab at sexy fish. After a lot of work, finally we were able to get something satisfactory. Walt had wanted it to look like girls in a harem.

The wall in the bedroom where I worked was plastered with a sandy finish and by holding black paper up against it and rubbing the pastels over the paper it produced a sparkle effect, suggesting an unusual underwater lighting. Of course, we didn’t rub all our drawings on the walls for the final product but the effect carried forward to the production.

Of course, Walt was all over the place when we were creating Fantasia. Everybody saw him every day, practically. And I complained to him about my assignment to develop a story with the music composed for a ballet. I had a dim view of male dancers, too. I asked if I could work on Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring instead. It seemed a lot more exciting than ballet.

I said to Walt, “I don’t know anything about ballet!” and he said, “Sit down for a minute. I’m going to do something for you.” And I thought he was going to give me another job like I had asked. But he telephoned somebody he knew who turned out was an impresario who’d brought the Ballet Ruse de Monte Carlo to town. Walt arranged for me to go and sit backstage for the engagement – a week and a half!

So, I did. I went back there and squatted around and made hundreds of drawings, and came to know the dancers and several ballets quite well. And I changed my mind about ballet, particularly about male dancers. I didn’t complain anymore and I resumed with a new appreciation the original assignment. I had a new attitude and it was quite a learning experience. I became friends with many of the dancers and I developed a respect for dancing and the dancers themselves that I’d never have had without that experience. I had no idea of the discipline and complete dedication required of dancers.

It was hot as hell in that little apartment. The walls of the apartment were quite thin and everybody set their record players on loud so you could hear what was playing in the next room and the next! The Toccata and Fugue in D Minor group was in the next bedroom. There was a lot of collaboration between that group and ours.

For a while, Walt was planning to include the Swan of Tuonela by Sibelius, a desperately sad piece which drove everyone crazy. When he decided to eliminate it, we were all relieved that we didn’t have to listen to it creeping through the walls and floor anymore.

Midway through the work on Fantasia, we all moved to the new Burbank Studios. The facilities were much nicer but they came at a price. We lost some of the musical and personal contacts. Since the rooms were more soundproof, we couldn’t hear the other music rooms playing and the groups became more and more isolated.

Midway through the work on Fantasia, we all moved to the new Burbank Studios. The facilities were much nicer but they came at a price. We lost some of the musical and personal contacts. Since the rooms were more soundproof, we couldn’t hear the other music rooms playing and the groups became more and more isolated.

I remember opening night at the Carthay Circle Theater. It was a terrific thrill. We had seats to ourselves and we sat there nervously waiting for the audience’s response. The full impact of the sound system was totally unexpected as the Fantasound traveled from screen side to side with the action, as well as from the back of the theater.

The opening scene, where the orchestra is being assembled was projected on the stage main curtain with house lights still on and most of the audience didn’t realize that the film had started. I heard someone say, “I think the picture’s started” and his companion said, “No, that’s just the orchestra filing in”. They thought it was a real orchestra! What a wonderful, sneaky way to begin the picture.

None of the animators had seen or heard it all put together before. We sat there in amazement, especially during Ave Maria when the voice kept moving in from various directions. We realized that we had been part of a milestone, and that nothing like it would ever be done again.

I worked on both background and layout and planning the dominant color for each scene. Again, we couldn’t use the whole color spectrum in every scene. We had to develop a sense of balance and completeness and save something for the peaks, keeping a good sequential relationship. Those were my major concerns.

I worked on both background and layout and planning the dominant color for each scene. Again, we couldn’t use the whole color spectrum in every scene. We had to develop a sense of balance and completeness and save something for the peaks, keeping a good sequential relationship. Those were my major concerns.

Color tells a story. What if an art director for a movie used a whole spectrum of colors in the first scene? Where would he go from there? There’s nothing left. He could only repeat himself. You have to develop a spectrum for a movie because people seem to like a sense of balance in what they are viewing and experiencing. Working on this film taught me about the relationship of color and music to emotion.

The Arabian Dance sequence required me to follow the sequence through the stages of layout, backgrounds and the modeling of the fish characters featured in it. Each scene had to match the changing moods of the music.

I can’t believe Walt’s courage in attempting such a thing as Fantasia. And I guess it worked. If you think about it, no one can listen to Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony or Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring without seeing the Disney images in their mind.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

I’m very glad that you were able to document John Hench’s remarks about working on Fantasia. I would have liked to hear more about his “planning the dominant color for each scene” and his thoughts on “the relationship of color and music to emotion”. This calls to mind something about Fantasia that has puzzled me for many years.

Beethoven had a condition called synaesthesia, in which a single stimulus will trigger responses in two or more senses. In Beethoven’s case, music caused him to “hear” colours (this is known as chromaesthesia); that is, every musical key, or chord, had a particular colour associated with it. To him, C minor was bright red, and he used it for some of his most angry and turbulent music, like the Pathetique Sonata and the Fifth Symphony. C-sharp minor, on the other hand, was silver, the key of his Moonlight Sonata. B minor was black, and Beethoven hardly ever used that key; I can’t think of a single instance of it in his music off the top of my head. But F major was a vivid green — and that, of course, is the key of his Pastoral Symphony.

Ordinarily one would expect an Arcadian fantasy in a pastoral setting to use buckets of green paint. Yet in the Pastoral Symphony sequence of Fantasia, there is very little green present. Most of it is in little touches like garlands, or Bacchus’s laurels. Trees, bushes, and lawns may be pink, purple, gold, or any colour at all EXCEPT green.

This puzzled me from the very first time I saw Fantasia, in a faded Technicolor print forty years ago. Gardeners have told me that a plain green background of grass or moss helps to attune the eye to the brighter colours of the flowers. I have to admit that I initially found the lack of green in the Pastoral Symphony disconcerting and a little hard on the eyes (Fred Moore’s winsome centaurettes notwithstanding). But seeing it in the restored version is really quite a magical experience, as though the colour green is made even more conspicuous by its absence.

In any case, Hench’s decision to downplay green in the Pastoral Symphony was an extraordinarily daring artistic move, an idea that only an artist of the very highest order could have come up with. This kind of creative thinking, that Walt Disney inspired in all of his artists at every level of production, is what makes Fantasia the masterpiece it is.

Thanks for the comment. I only wish I had had the foresight to record and transcribe more of the special lectures I got the opportunity to attend over the decades including ones at the Disney Institute. I guess I should be grateful I was able to save some of that information including this brief lunch time talk with Hench. I always thought somebody, especially Disney, was documenting these things but it turned out that was not the case.

Speaking of color, Hench could talk endlessly about color but here is a little animation anecdote about the color in that Pastoral Symphony scene. . According to Disney legend, frustrated in his search for a new and different color for a layout from Hugh Hennessy for the Greek mythological world in FANTASIA, background painter Ray Huffine sulked in his room during his lunch hour. He had tried vainly everything he had on his artist’s palette but nothing could quite capture the instant allure of Mt. Olympus that would only be seen briefly at the beginning of the sequence.

He opened his home-packed lunch from his wife and discovered among other things, a small jar of Mrs. Huffine’s best homemade boysenberry jam. Surprised and inspired, he opened the jar and laid a very light boysenberry wash over the background. He was delighted at the results of obtaining an out of the ordinary but perfect purplish hue. Years later, the memory of that discovery still brought a smile to his face as he realized that audiences never suspected that the marvel of Mount Olympus was enhanced by his wife’s boysenberry jam.

What a wonderful story! It explains why the purple foliage in that scene seems so organic and natural. Just imagine how different that establishing shot would be if Mrs. Huffine had packed apricot jam that day!

Thank you, and may I take this opportunity to say how much I’ve enjoyed your writings on animation over the years, going back to Cartoon Confidential. Keep ’em coming!

“L-L-L Leopold!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NSOLhODlZF0

That’s a fine performance of the Toccata and Fugue from 1967, when Stokowski was 85. I was a little surprised to see him turning the pages of the score; since he first recorded the piece 40 years earlier, he must surely have had it memorised. A couple of peculiarities about Stokowski’s conducting: he did not use a baton (referenced in “Long-Haired Hare” when Bugs Bunny, as “Leopold”, breaks the baton in two and throws it away), and he did not like synchronous bowing in the string section. What the orchestra thus lost in precision, it gained in passion. Unfortunately Stokowski’s Bach arrangements are seldom performed today, now that musicians generally strive for authenticity in Baroque period performance practice. These works are very difficult, but they can be dramatic and stirring under a good conductor. I’ve played most of them and am especially fond of the Chaconne in D minor, a marvelously textured and complex orchestral arrangement that Stokowski adapted from a movement for solo violin!

Having appreciated and studied Fantasia for many years, I have come to the realization that it is not merely a collection of random unrelated segments, but rather a unified whole that deals with a range of profound themes. An over-arching theme could be “The Secrets of Nature and the Mysteries of Life, Death, and Regeneration, or the Cycles of Life.” Water is a motif that runs throughout, and water is of course the essence of life. The Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, though abstract, contains images suggestive of water and rain, of death and the afterlife. The Nutcracker Suite is a nature ballet that depicts and celebrates the life cycles, and again utilizes water sequences. In The Sorcerer’s Apprentice it is nothing less than the power of the cosmos into which Mickey delves, with the water motif again prevalent, as well as the regeneration theme in the endless replication of the brooms. Rite of Spring takes us back to the origins of life, out of water, and covers millions of years of evolution from single-celled organisms to dinosaurs, culminating in the fiery destruction of the dinosaurs and yet another regeneration of the life cycle. The Pastoral Symphony is about regenerative cycles of courtship, romantic love, and the power of the gods. Even the Dance of the Hours with its amusing hippos and alligators represents another life cycle in its depiction of the hours of the day. Night on Bald Mountain of course taps into the primal forces of evil and as in Rite of Spring involves volcanic power and as in Pastoral depicts the power of supernatural beings, and as in Sorcerer’s Apprentice the power of cosmic forces unleashed. Then Ave Maria caps it off by dispelling the dark forces and bringing forth the light through misty, watery veils, affirming faith in the forces of good and the afterlife, as suggested in the first segment Toccata and Fugue, re-emphasized and brought forth with vivid power in the finale. Though it’s hard to condense into a few words, there is definitely a sense of major thematic unity running through the entire film of Fantasia. No wonder Walt Disney was so proud of the accomplishment. He never lost an opportunity to make reference to Fantasia in the course of the many television hours he hosted.