Suspended Animation #293

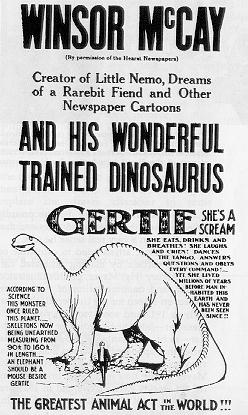

A pantheon of legendary names from early animation, including Paul Terry, Max and Dave Fleischer, Pat Sullivan, Otto Messmer, Richard Huemer, Shamus Culhane, I. Klein, Walt Disney, Ub Iwerks and Walter Lantz, among many others, have publicly admitted over the years that seeing cartoonist Winsor McCay and his vaudeville act with the animated film of his playful Diplodocus was what inspired them to get into the animation business.

In November 1914, McCay, in conjunction with William Fox’s Box Office Attractions Company (the forerunner of Twentieth Century Fox), later released a short black-and-white silent film to movie theaters of his vaudeville act. It included a live-action prologue and epilogue with inter-titles that showed McCay’s on-stage dialog.

The Three Ages

In the film, using stop-motion clay models, Keaton made his entrance on the head of a brontosaurus reminiscent of Gertie.

Winsor McCay was a prolific and talented artist. Today, he may be best known for the color Sunday comic strip Little Nemo in Slumberland (about a young boy who falls asleep and finds himself in a fanciful world) that he wrote and drew, but he also produced hundreds of editorial cartoons, advertisements, and other comic strips, as well as being a top-ranked act on the vaudeville circuit.

In 1906, he began his career on the variety stage with a routine where on a large easel and with orchestral accompaniment, he did a highly popular “lightning sketch” act where he quickly drew freehand everything from funny caricatures to his own comic-strip characters.

McCay did not create the first animated cartoon (although he often claimed that he had), but he established a process for doing animation (including key drawings, effective registration of images to prevent “jitters”, and the concept of “cycling” action that reused drawings) that would later be refined by others into what became the standard way of producing animation.

McCay never applied for a copyright or patent on any of his techniques. He told a newspaper colleague who was urging McCay to copyright everything, “Any idiot who wants to make a couple of thousand drawings for a hundred feet of film is welcome to join the club.”

McCay never applied for a copyright or patent on any of his techniques. He told a newspaper colleague who was urging McCay to copyright everything, “Any idiot who wants to make a couple of thousand drawings for a hundred feet of film is welcome to join the club.”

During the summer of 1912, McCay was telling interviewers that his next animated film would include dinosaurs. He told a film trade magazine: “I have already had a conference with the American Historical Society looking to a presentation of pictures showing the great monsters that used to inhabit the earth.

“There are skeletons of them on exhibition and I expect to draw pictures of these animals as they appeared in real life thousands of years ago and show them as they trampled their way through dense jungles, ate a stump or pulled down a tree, or had a battle with others of their kind.”

McCay was supposedly inspired by a dinosaur skeleton put on display in 1905 at the American Museum of History in New York. It was the first such creature to be reconstructed and displayed to the public and was identified as a Brontosaurus. In actuality, it should have been more properly identified as an Apatosaurus excelsus.

For reasons known only to McCay, he referred to his cartoon dinosaur as a Diplodocus, which is another sauropod genus entirely.

McCay began production in earnest on Gertie during the summer of 1913. He hired a next-door neighbor, John A. Fitzsimmons, a 20-year old art student, as his assistant.

Fitzsimmons primary responsibility was the mind-numbing task of carefully retracing the background from a master drawing 6” by 8” onto thousands and thousands of pieces of rice paper in Higgins black ink. The rice paper was thin enough so that Fitzsimmons could easily see through it to trace.

Over the months, McCay drew roughly 10,000 drawings of the characters (by his own account) to make approximately five minutes of animation. There were no schools or books that taught animation so he had to invent a method to do animation.

McCay recalled: “When [Gertie] was lying on her side, I wanted her to breathe and I could come to no exact time until one day I happened to be working where a large clock with a big second dial accurately marked the intervals of time. I stood in front of this clock and inhaled and exhaled and found that, imitating the great dinosaur, I inhaled in four seconds and exhaled in two.

McCay drew 64 drawings of Gertie inhaling and 32 drawings of her exhaling to get one cycle. To save on “pencil mileage”, McCay created the animation concept of “cycling”, which meant re-filming the same set of drawings for a continued action. “I only drew her breathing once,” McCay said, “but I photographed that set of drawings over 15 times.”

Newspaper illustration.

Gertie made her first appearance at the Palace Theater in Chicago in February 1914 as part of McCay’s vaudeville act that still included the lightning sketches and a screening of his animated short The Story of a Mosquito (sometimes called How a Mosquito Operates), that was first shown in January 1912.

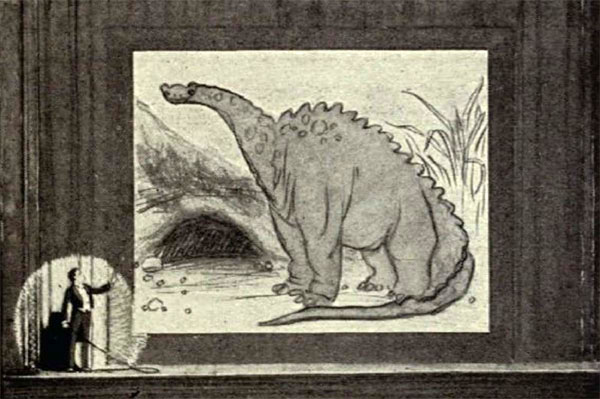

McCay would stand on the apron of the stage dressed in his black cutaway tuxedo, but holding a huge bullwhip like an animal trainer might use to handle a lion. He engaged in some “patter” with the audience, then drew a sketch of Gertie on a large easel and told the crowd he was going to introduce them to “the only dinosaur in captivity”.

With a crack of his whip, the movie screen sprang to life and McCay coaxed the shy Gertie to poke her head from out of her cave from behind some rocks in the distance. She had the personality of a curious puppy or small child, despite her massive height and girth.

McCay commanded her to do a series of tricks such as lifting her legs one at a time and bowing to the audience. At the end of the film, it appears as if McCay walks into the animated scene himself as a miniature caricature in tuxedo and carrying the same type of whip. He steps into Gertie’s open mouth and is gently lifted and set down on her back. He bows and Gertie carries him off screen.

During the presentation, she responded to McCay and to the audience as if she were a live performer, thanks to McCay’s precise timing. The film is filled with little bits of natural action, like when she licks her lips and smiles after gobbling the tree trunk. It was an interactive experience and charmed every audience.

Some hecklers in the audience were initially skeptical, as McCay reported in 1919: “When the great dinosaur first came into the picture, the audience said it was a papier-mache animal with men inside of it and with a scenic background. As the production progressed they noticed that the leaves on the trees were blowing in the breeze, and that there were rippling waves on the surface of the water, and when the elephant was thrown into the lake the water was seen to splash. This convinced them that they were seeing something new—that the presentation was actually from a set of drawings.

Next Week: the rest of the story in Part Two including the story of the bogus Gertie cartoon, McCay’s planned sequel and more. Thanks to the scholarship of animation historians, like John Canemaker and Donald Crafton, McCay’s work, especially Gertie, has been brought to the attention of the general public.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

I first learned about Winsor McCay from a very good article I read in the Cincinnati Enquirer some thirty years ago. McCay lived in Cincinnati from 1891 to 1903, and his time in that city laid the groundwork for his later career.

McCay came to Cincinnati (from Detroit, by way of Chicago) to work as a lightning-sketch artist in the city’s downtown dime museums. It was in one of these that he saw a demonstration of an Edison motion picture — McCay’s first exposure to the medium of film. He augmented his income in those days by painting signs and, a natural showman, he found that he could attract crowds of onlookers while he worked. He was soon offered work as a newspaper illustrator and eventually became the Enquirer’s art director. It was there that he drew his first comic strip, but it ran only briefly before he moved on to New York and greater triumphs. He is honoured today in Cincinnati with a Little Nemo mural covering the side of a building downtown.

As for McCay’s confusion between Brontosaurus (now Apatosaurus) and Diplodocus, that’s quite understandable. As you mentioned, the first mounted skeleton of a Brontosaurus (or indeed of any Sauropod dinosaur) was put on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York in 1905. However, in 1898 a fossil femur of what turned out to be a Diplodocus was discovered in Wyoming, and newspaper reports of the discovery were accompanied by illustrations of a Brontosaurus. Andrew Carnegie, then the world’s richest man, financed an exhibition to unearth the skeleton for his museum in Pittsburgh. Before this Diplodocus skeleton was mounted (a new building had to be constructed to accommodate it), Carnegie had plaster casts made of all the bones and gave them to major museums all over the world. This was big news, and in the years immediately prior to the making of Gertie, Diplodocus — not Brontosaurus — would have been the genus of dinosaur most familiar to the general public. Today the Apatosaurus skeleton in the AMNH is upstairs in the Hall of Saurischian Dinosaurs, while the Diplodocus cast takes centre stage in the museum’s entrance hall, rearing up dramatically on its hind legs — which I strongly doubt the animal ever did in life.

For many years Diplodocus was the longest dinosaur known, although other sauropods like Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus were considerably more massive. The tail alone accounted for about half its length. Gertie is not nearly slender enough to be a Diplodocus, but so what? What matters is that McCay brought an extinct titan to life — “animation” in a literal sense — and inspired a generation of pioneers in this new art form.

As much as I love Gertie, it’s the Mosquito film that really blows my mind!

I am a giant fan of her (and his!) Thank YOU!!!!

I love Chuck Jones’s quote about McCay:

“It is as though the first creature to emerge from the primeval slime was Albert Einstein; and the second was an amoeba, because after McCay’s animation it took his followers nearly twenty years to find out how he did it. The two most important people in animation are Winsor McCay and Walt Disney, and I’m not sure which should go first.”

Looking at Gertie, it’s hard to believe it was made 106 years ago. It has everything you expect from modern character animation, save for sound and color. Gertie moves with believable weight, remarkable grace, and most importantly, personality. It took over a quarter century for animators to reach the same level of draftsmanship with Disney’s Fantasia (which is celebrating its 80th anniversary today) and its masterful handling of dinosaurs.

O.K, so Gertie was not the first animated character, sure. However, she was, to use TV Tropes terminology, the Trope Maker for animation as we know it. This is similar to how Superman was not the first comic book superhero but the one that really established the popularity and essence of that archetype.

When my daughter was around 10, I took her to the Toonseum in Pittsburgh. They were showing Gertie on a small screen near the front desk. My daughter said “Oh, Gertie The Dinosaur!” The desk attendant stated something about the film that was incorrect. Not only did my daughter correct him, but she went on for about three minutes telling him the story of Gertie and McCay’s Vaudeville show with McCay’s interacting with the film. The attendant was amazed (and gracious when she corrected him).

I think I first showed Gertie to her when she was, perhaps, four. At first, she loved the way Gertie dances (I mean, who doesn’t?). Later on, she began to recognize and appreciate the emotion that McCay put into Gertie. When she was a senior in high school, she wrote her senior thesis on the history and evolution of the American animated cartoon. Even today, many years later, she is an animation aficionado and historian, second in this household only to her dad. I call her “Mini Me”.