Back in August 1995, on a hot summer day in Hollywood, I interviewed Virgil Ross. He lived in a modest house just up the hill from the famed Hanna-Barbera building and across the pass from Universal Studios, where he had worked as an animator for Walter Lantz sixty years earlier. That’s why I was visiting that day. I brought with me VHS tapes of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons to show him and pepper him with questions about those days long ago.

His memory was astoundingly good, even under pressure from a young punk like me to view cartoons on his TV and to remember which scenes he had animated and which ones were done by others—with their names, please! It makes me smile now to think what a good sport Virgil was. Honestly, it likely was grueling, chugging down memory lane with an inquisitor like me, pencil at the ready and tape rolling, as those recollections kept burbling up.

Watching the Cartune Classic Toyland Premiere, he recognized the hand of Manuel Moreno and said, “Moreno drew a good Santa Claus.” He had moments of surprise, suddenly remembering that he’d done the groundhog pointing in Springtime Serenade and some familiarity with the piano playing in Do A Good Deed because of how Oswald hits the bass notes. Virgil played piano so he felt that he animated that bit with the knowledge of how he himself would strike the keys. Speaking to me in 1995, he lamented that in just the prior two years he had effectively given up playing on account of his advanced age.

The sequence that really stood out for him, which he loved watching again, was the extended chase sequence in Towne Hall Follies in which the heroine and villain run out from under the fallen cloth and the then continue up on the tightrope. For this, he remembered he had won praise from Tex Avery, which turned out to be a fortuitous moment to catch his favor. In 1935, Avery was not only standing in for Bill Nolan as an uncredited director at Universal but was also quietly negotiating with Leon Schlesinger to form another cartoon unit that became the legendary Termite Terrace crew.

Being tight with Avery was his ticket to make the jump over to a new studio, which eventually was an historic event leading to the development of the classic Warner Bros. brand of humor. However, Virgil mentioned to me that immediately after his departure there were things he missed. At Universal, the cartoon department was on the studio lot. As he walked around, movies were being made in the soundstages all around him and stars were casually seen on the grounds. The animation building had been in disrepair, but Lantz had gotten the studio to knock out the old termite-chewed wood flooring and to replace it new. Suddenly, though, Virgil was back working among termites and a tattered floor. As historic as his move to Schlesinger may have been, it sure lacked for glamor.

When he started at Universal in 1933, he had been assigned to Avery as an assistant, so he was afforded a keen study of his drawing style, saying that Tex drew “crudely” but that the action was “out of this world,” even adding that “I didn’t see how they could ink some of that stuff.” Well, presumably they could because Virgil cleaned up the drawings. He enjoyed the challenge of working to make sense of the outrageous sequences and he eventually became an animator himself around the time he indicated to me that Tex became the de facto director for the Bill Nolan unit.

As fate would have it, Tex started as Nolan’s assistant, adopting his straight-ahead style of animation. This was already growing old-fashioned in the 30s, as animators embraced the pose-to-pose method used at Disney, but in Avery’s case it lent to his overall improvisational technique. The limitations that he had as an artist and animator in some ways led him to cultivate the workaround methods that contributed to his innovative surprises and distinct approach as a director.

In my conversations with Virgil Ross and also Ed Benedict, they mentioned that he tended to draw Oswald with big eyes. As a telltale sign of Avery’s work, this almost seems like a cartoon manifestation of the wide-eyed dreamer looking to invent new ways to push the envelope on animated gags. It was these sorts of observations that I loved to hear about, insights that I could use as a ‘decoder ring’ to glean more from watching the old cartoons.

Ed Benedict could be especially blunt in this regard. Among his opinions were: Bill Nolan drew too quick, Lantz couldn’t draw (and usually didn’t), Avery was “way out,” and Ray Abrams drew especially well but might make the hands or eyes too big. Abrams, who also drew for Winkler and Disney, was one of the guys whose style exemplified how Oswald looked in the early 30s. Manuel Moreno, everyone agreed, was top-flight and drew “smooth as glass,” one of the best pure talents at Universal. The shift in Oswald’s design to a cuter rabbit, first in 1933 and then completely redesigned in 1935, might even be seen as a transition from the Abrams style to Moreno’s growing influence.

Ed Benedict could be especially blunt in this regard. Among his opinions were: Bill Nolan drew too quick, Lantz couldn’t draw (and usually didn’t), Avery was “way out,” and Ray Abrams drew especially well but might make the hands or eyes too big. Abrams, who also drew for Winkler and Disney, was one of the guys whose style exemplified how Oswald looked in the early 30s. Manuel Moreno, everyone agreed, was top-flight and drew “smooth as glass,” one of the best pure talents at Universal. The shift in Oswald’s design to a cuter rabbit, first in 1933 and then completely redesigned in 1935, might even be seen as a transition from the Abrams style to Moreno’s growing influence.

It was this period of transition that saw Bill Nolan get left behind and then leave the studio in 1934, opening the door for Avery’s rise. In a way, having Tex assert his dynamic, aggressive gags in the Oswald cartoons stood in contrast to what Lantz was doing with his ‘prestige’ cartoons in two-color format. Because Disney had locked up the rights to full Technicolor, used impressively in the Silly Symphonies, Lantz only had the two-strip palette to use when he followed suit and began his Cartune Classic series, after having been a pioneer in color format with King of Jazz.

The problem with this musical series was that it seemed music-first and comedy-second. Compared to what Tex Avery, Cal Howard, and Leo Salkin were dreaming up in their Oswald gag sessions, the sequences that one finds in a Technicolor Cartoon Classic are almost stately and decorous. In Toyland Premiere, we have some fun seeing caricatures of movie stars, but as an example, there is an homage to Bing Crosby crooning that falls short of really poking fun. It goes for smiles, not big laughs. At least when we see vintage Universal monsters in color, there is ironically a little more leeway for parody with these stiff-limbed creatures, but even a comic bit with Frankenstein threatening Laurel and Hardy doesn’t really elicit much of anything.

Virgil told me that Ray Abrams used to kid him that the Lantz pictures weren’t really that funny. And arguably, even though Disney cartoons had redefined the notion of funny—innovating a strong mix of characters and story—it was the tepid ‘imitate Disney’ trend that was taking the wild appeal out of Oswald. The Technicolor ‘tunes may have gotten the royal treatment from Lantz, but it was the b-picture approach to the black & white run of regular Oswalds, with some of the creative direction delegated to Avery, where the humor stayed more punchy and bold.

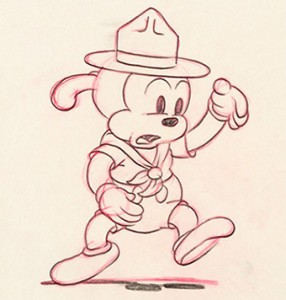

A malaise set in at the studio by mid-decade, exasperated by the worsening Depression-era finances that Universal was facing. Amid an atmosphere of uncertainty, Avery stayed true to his compass and kept his focus on gags. In truth, he didn’t always succeed. However, he knew what he was going for and with each try he was slowly honing his comic timing and inventive sense of humor. As a result, a cartoon like The Hillbilly feels a bit sharper and funnier compared to a softer approach seen in Do A Good Deed, for instance, where Oswald is a scoutmaster. When Avery took the meeting with Schlesinger in 1935, he explained that he had just directed a few cartoons at Universal and, with this experience, he was ready to direct a series.

A malaise set in at the studio by mid-decade, exasperated by the worsening Depression-era finances that Universal was facing. Amid an atmosphere of uncertainty, Avery stayed true to his compass and kept his focus on gags. In truth, he didn’t always succeed. However, he knew what he was going for and with each try he was slowly honing his comic timing and inventive sense of humor. As a result, a cartoon like The Hillbilly feels a bit sharper and funnier compared to a softer approach seen in Do A Good Deed, for instance, where Oswald is a scoutmaster. When Avery took the meeting with Schlesinger in 1935, he explained that he had just directed a few cartoons at Universal and, with this experience, he was ready to direct a series.

After making the cartoon Golddiggers of ’49 on spec, he was put on contract and the Termite Terrace days had begun. Sid Sutherland and Virgil Ross left Universal to join the new venture. In fact, Virgil told me that Lantz told him not to expect his job back if it failed. He also said that Avery, in order to persuade him, had offered $35 in weekly pay, but when Schlesinger only paid him $30 that Avery kicked in $5 of his own money each week to honor the promised amount.

Of course, in the later years of his career at MGM, Tex created one of his signature visual gags: eyes that explode out of Big Bad Wolf’s sockets when he sees Red. So perhaps it’s no surprise that in the early 1930s Tex was perceived as drawing Oswald off-model with eyes a little bigger than other artists. Abrams, too, was another who favored pushing the style to feature bigger eyes, and a trove of Ray Abrams’ art is now appearing courtesy of his son William. It’s been a real treat to have those here on Cartoon Research. If you have a look at the envelope artwork Ray drew, from William’s post two days ago, you can see those big, big eyes, a classic touch from the era.

However, back on that summer day in 1995, after I had probably exhausted Virgil with my interview, I’ll never forget when his eyes narrowed. You have to remember, Virgil Ross was eighty-eight years old and frail. We were watching a cartoon when his head dipped forward in a slump. I have to admit I panicked, thinking the worst might have just happened.

However, back on that summer day in 1995, after I had probably exhausted Virgil with my interview, I’ll never forget when his eyes narrowed. You have to remember, Virgil Ross was eighty-eight years old and frail. We were watching a cartoon when his head dipped forward in a slump. I have to admit I panicked, thinking the worst might have just happened.

“Virgil? Virgil? Virgil!”

To my great relief, he woke up. Just a little case of nodding off. I realized it was getting time for me to wrap it up and to thank him for his generosity. It remains one of the most useful and historically significant interviews I’ve ever gotten, especially in regard to what I came to see as the Universal Cartoon Dept. serving as a proving ground for Termite Terrace. By the time the Warner Bros. cartoons really came to fruition, they could trace a path of influence back to Oswald.

For a deeper look at that topic, see my article “Tex Avery: Apprenticing the Master,” which appeared in Animation Journal in Fall 1997 or my chapter in the 1998 anthology What’s Up, Tex: Il Cinema di Tex Avery. Virgil provided me some invaluable insights that day and the mementos he shared of his career were fascinating. He still had the sketches that got him his first job at Mintz in 1930.

To all the families and descendants of these early animators, a generation that is now gone, it’s with profound gratitude when such items are made public to add to the historical record. To William Abrams, a giant thank you for sharing the work of your dad. And to guys like Ray and Tex, rest in peace, we’ll always have those Big Eyes of your cartoon ambitions.

This surviving sketch circa 1930 from Universal represents one among the thousands of gags drawn up by the dreamers who changed the animation industry in the Thirties. Courtesy of UCLA Library Special Collections

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

I didn’t know Virgil worked at Lantz in the 1930’s. I know he worked there during the winding (and depressing) years of the studio in the late ’60’s-early 70’s.

Were there any other animators that were also musicians? I remember once reading that Virgil Ross briefly worked as a pianist during the shutdown of Warner Bros.’ animation studio in the 1950’s

Steven, there’s definitely been a long tradition of musician-animators, and exactly how that mix influences each field is an open question, but it’s had a lot of fun results. I didn’t know that Virgil worked briefly as a pianist during the shutdown; he humbly described himself to me as “not an aficionado.” One of the chief means of musical expression by animators has been through their cartoons. In some of my recent blogs, you can see the example of Pinto Colvig, who stopped animating but remained involved musically on 1930s cartoons. Disney’s in-house band Firehouse Five Plus Two released popular albums. And more recent examples would be Screaming Lederhösen music for Ren & Stimpy, David Silverman’s flame-spouting tuba, or Seth McFarlane’s impressive musical work.

Very interesting, I’m really enjoying these articles by the way, it’s always great to learn more about these talented people