Universal’s founder, Carl Laemmle, was a paragon of Hollywood ambition, even if MGM’s Louis B. Mayer is the producer who remains the all-time cigar-chomping icon. When Laemmle brought Universal Pictures to Hollywood from New York, he didn’t just open a studio lot—he built Universal City. To this day, with its own zip code and city limits, you can easily spot it on a map. When he opened it to the public, on March 15, 1915, Laemmle even conjured a flood that unexpectedly swept out into a crowd of over 10,000 onlookers.

And so it was: Let there be Lights, Camera, Action! The pandemonium from his flood left him unbowed. Despite some auspicious disasters during opening week, not to mention the snickering from rivals who deemed the studio to be “Laemmle’s Folly,” the Silent Film era proceeded to be generally good to Universal’s fortunes. But then when “talking pictures” arrived, a transitional period that roiled the movie industry, the studio navigated some tricky waters of its own.

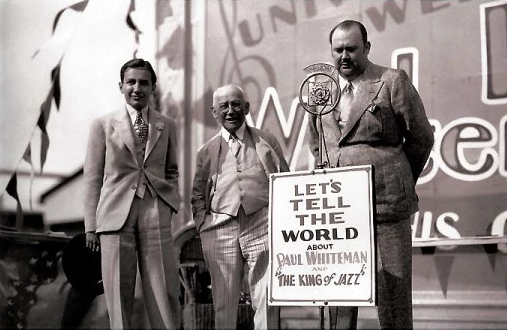

That’s when Walter Lantz and bandleader Paul Whiteman enter the Universal story. I have previously used a Great Gatsby metaphor to describe what it was like for Walter Lantz to arrive in Los Angeles during the Jazz Age, those Roaring Twenties. He crossed the country, New York to L.A., in his trusted Locomobile racecar. He arrived as a guest of Bob Vignola, his pal-who-made-it-big-in-Hollywood, and by chance on the very day he arrived Vignola was having a huge party. Lantz was overwhelmed by the movie stars he met there, quite an introduction to tinseltown.

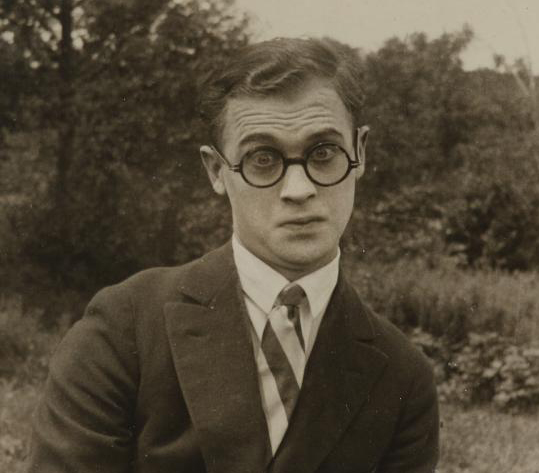

Living much like Nick Carraway did at Gatsby’s estate, and cast eagerly into a world of casual party-going, Lantz lived at Vignola’s house and made acquaintances over drinks and merriment with Harold Lloyd, Gloria Swanson, Marion Davies, the Talmadge sisters, and Buster Keaton, among many others. In fact, his meeting with Harold Lloyd may have been the most noteworthy because his film persona at Bray Studios in previous years had been inspired to some degree by Lloyd’s own screen character, right down to the round glasses. Walter Lantz estimated he brought somewhere between $15,000 and $17,000 with him that he saved up from New York, a nest egg to get him started in his new life without fear he needed to find work right away. And after his very first day partying in La La Land, it was clear that he might not want to rush it, either.

My most recent blogs cover a lot of what transpired over the next two years, including a fortunate turn-of-events with Pinto Colvig and then a weekly poker party with Hollywood producers that had the escalating effect of landing him the plum job of being in charge of Universal’s animation division. Suddenly, after a slow rolling start, Lantz had been thrust into the fast lane. His technical proficiency and previous experience directing made him the go-to guy to make things happen amid the looming complexities of sound film production.

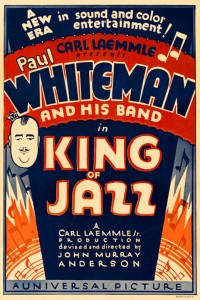

It may have been one thing to learn-on-the-go with the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons, which he inherited and continued to produce, but quite another to be tapped for a prominent role contributing to Universal’s big prestige picture for 1930, King of Jazz. He had been slowly finding his way with synchronization, basically using the shorts releases themselves as his test films, and then stepping up on to that biggest of stages, an Oscar-worthy feature film shot in new two-strip Technicolor.

This was a big-budget movie filled with lavish musical numbers. The wildly popular bandleader Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra were the center attraction. The premise was a journey through his Scrap Book, which is a loose framework for the revue. The sequences return to a visual motif of this giant book and the vignettes are introduced as chapters. The very first chapter is an animated prologue, four minutes in length, produced by Walter Lantz and Bill Nolan, referred to in production notes as “A Fable in Jazz.”

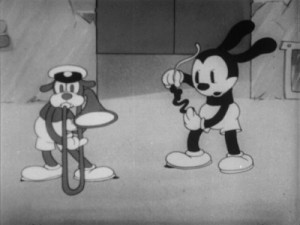

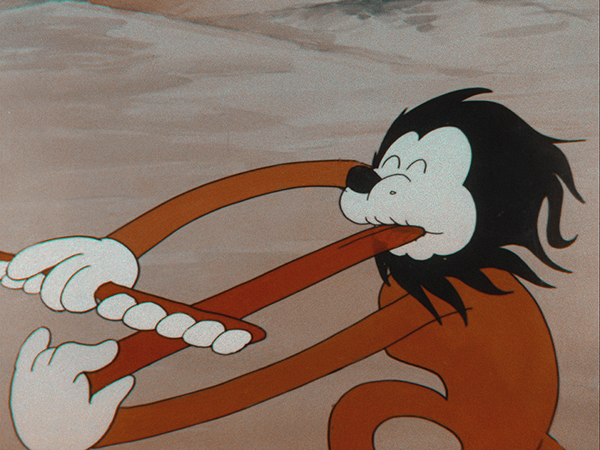

This sequence was the first animation in Technicolor, though the production value was not as big a leap forward from the regular Oswalds as it could have been, even despite the historic debut of its two-strip color technique. In it, Whiteman sets out to shoot a lion during a big game hunt, but then they make music together instead. The role of the cartoon was to create a whimsical backstory best summed up by the cartoon’s closing line: “And that’s how Paul Whiteman was crowned the King of Jazz.”

We see a big crown-like swelling on his balding head from a coconut thrown by a monkey. It’s kind of funny that Universal took out a million dollar insurance policy on Whiteman, only to have the animators waste no time at all beaning him hard on the head within the opening minutes.

A reason I’m writing this is that I’ve just seen Universal’s wonderful restoration of King of Jazz, completed last year. This was an especially notable effort because it required piecing together parts from a number of separate elements, requiring both detective work and technical expertise. The restorative effort was led by Peter Schade and completed in-house by NBCUniversal Global Media Operations and NBCUniversal StudioPost.

Schade’s team had the film assets scanned digitally and placed into a 4K workflow, where frames could be evaluated, cleaned and assembled to re-sync them to a surviving soundtrack negative that ran the full 105 minutes of the original 1930 release. And I’m grateful that Peter could personally attend our LMU screening of the movie and reveal some of the details of this wonderful achievement, nothing short of bringing back a film that had long since ceased to be available in its original glory.

One of the things striking about King of Jazz is its opulence. This was a film in development prior to the stock market crash of 1929, and yet was released into an economy sliding into worsening Depression. It’s basically a 1930 movie that keeps partying like it’s 1929. It has a dizzying array of musical performances, dancing, and terrific lighting and sets. Carl Laemmle really spent generously when he made it and the movie won an Oscar for Best Art Direction.

One aspect of seeing it in such high-def clarity is to notice details, such as the prologue’s cel paint, which ought to be opaque, but shows transparency in some portions, such as the lion’s tongue. This was surely a result of having no available color cel paints, which were all mixed as shades of gray at the time, so the Universal staff used less compliant commercial paints and initially suffered some production setbacks like cracking and flaking on the cels.

In 1930, Nolan was the artist making the backgrounds for the Oswalds. Ed Benedict once told me that Nolan was the only person at the studio who had the luxury of having two desks, and I’ve wondered recently if that was the justification for his second desk or just a perk of his senior ranking as co-producer with Lantz. Nonetheless, in a short time it was Ernest “Ernie” Smythe who assumed that role at the studio, drawing both the layouts and final backgrounds on paper.

The backgrounds had always been simple for the early 30s black & white Oswald cartoons, just pencil rubbings. Benedict described to me that Smythe used suede-wrapped stumps to smudge the graphite. One of the glaring missed opportunities on King of Jazz is that they used a similarly basic, muted approach, what seems like nothing more than simple watercolor washes instead of bringing in a true background painter. Mostly it is the bold reds and greens of the cel animation that give this “Fable” its pop of Technicolor.

However, let me advance another theory. Considering the difficulty Lantz reported with color paints cracking (any that was not black, white or mixed as gray), perhaps he needed to thin them with solvents before they would adhere to cels. If this was the case, then that explains the translucence of reds. If this transparency served to make the backgrounds visible through red portions, then that may have warranted leaving the backgrounds plain to mitigate the appearance of partially ‘see-through’ characters. A careful look at the four-minute cartoon reveals there is a lot of strategic placement of red overlays so as not to pass them over any high-contrast area of the background.

However, let me advance another theory. Considering the difficulty Lantz reported with color paints cracking (any that was not black, white or mixed as gray), perhaps he needed to thin them with solvents before they would adhere to cels. If this was the case, then that explains the translucence of reds. If this transparency served to make the backgrounds visible through red portions, then that may have warranted leaving the backgrounds plain to mitigate the appearance of partially ‘see-through’ characters. A careful look at the four-minute cartoon reveals there is a lot of strategic placement of red overlays so as not to pass them over any high-contrast area of the background.

If Lantz and Nolan were forced to adopt this practical approach, then I deem them rather clever producers because this creative constraint has, I believe, gone unnoticed for over eighty-five years. In the image above, of the lion, the transparency is revealed because the red tongue is on a second cel layer that overlaps the lion’s jaw below. Click the image for a higher resolution view.

Everyone was pleased with Lantz after his first year at the studio, including how he handled the movie prologue. He was signed for a renewed contract. The bigger impact of this special project wasn’t Lantz’s influence on King of Jazz, but the other way around. A musical arranger named James Dietrich, often found banging around prodigiously on pianos, had come along with the band to live at the studio—the musicians’ communal hall was dubbed the Paul Whiteman Lodge—during the protracted making of the feature film in 1929.

Dietrich had been living in New York, working for John Murray Anderson, and became quite enamored of his new Hollywood lifestyle. It’s not difficult to see why he felt so welcome here. Universal filled the lodge with amenities, including a rec room with billiard table. The musicians were all provided free cars. Meanwhile, amid the frivolity at the lodge, Wall Street crashed back in New York, setting off regional bank panics.

Dietrich had been living in New York, working for John Murray Anderson, and became quite enamored of his new Hollywood lifestyle. It’s not difficult to see why he felt so welcome here. Universal filled the lodge with amenities, including a rec room with billiard table. The musicians were all provided free cars. Meanwhile, amid the frivolity at the lodge, Wall Street crashed back in New York, setting off regional bank panics.

When the movie wrapped, Dietrich stuck around and signed to stay with Lantz. In particular, he had made a strong case by doing a fine job scoring the animated “Fable” and adapting to the technical necessities for timing and animation. Not surprisingly, the subsequent Oswald cartoons had a lot in common with King of Jazz. It seems almost like Pinto Colvig’s musical interpretations and Dietrich’s replication of King’s showtunes became the twin pillars of influence on the Universal cartoon soundtracks of the early 30s.

To put this in perspective, if you watch King of Jazz and then watch the Oswald cartoons that released in the year after, it becomes especially apparent how many snappy numbers are pulled from the Whiteman songbook. Even exempting My Pal Paul (1930), which was meant as a companion cartoon starring the bandleader, there are lots of other Oswald films that are reliant on King of Jazz without making any specific reference to it. Dietrich simply appropriates songs and the comedic musicality of the movie’s soundtrack.

For instance, both The Fisherman (1931) and Radio Rhythm (1931) make use of “Happy Feet,” which Bing Crosby and the Rhythm Boys sing in the feature. Mars (1930) opens with a rendition of “Bench in the Park.” College (1931) extensively uses the song, “I Like to Do Things For You,” which Grace Hayes sings in the movie while she smacks around William Kent. Also, Hot Feet (1931) uses a song with the refrain of “Lemonade” that I cannot place, but having just seen King of Jazz, I can attest that it shares the same uptempo comic sensibilities of the movie’s numbers.

There are other examples, too, of songs pulled from King of Jazz, but the cartoon that really stands out for its imitative soundtrack is The Bandmaster (1931). It shares a total of three songs with the movie revue: “A Bench in the Park”, “Happy Feet” and “Ragamuffin Romeo.” For the last song, there is an animated sequence of rag dolls dancing that matches how the song was interpreted in the Whiteman musical with a professional dance duo, Marion Stadler and Don Rose, moving like dolls in a routine they had made famous on stage.

There are other examples, too, of songs pulled from King of Jazz, but the cartoon that really stands out for its imitative soundtrack is The Bandmaster (1931). It shares a total of three songs with the movie revue: “A Bench in the Park”, “Happy Feet” and “Ragamuffin Romeo.” For the last song, there is an animated sequence of rag dolls dancing that matches how the song was interpreted in the Whiteman musical with a professional dance duo, Marion Stadler and Don Rose, moving like dolls in a routine they had made famous on stage.

This astounding restoration of King of Jazz is notable for many other reasons, but for cartoon fans it provides a terrific new context to watch the Oswald series and to compare the animated performances scored by James Dietrich against the epic showstoppers of Paul Whiteman and his Orchestra. Universal has deservedly won praise for restoring this gem to its proper luster. For Peter Schade and his team, that has become a personal triumph, getting to witness new generations enthralled once again by its showmanship.

Images above from King of Jazz courtesy of Universal Studios, All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgments to Peter Schade and Aaron Rogers of NBCUniversal for their assistance with this column. For more information on the making of this film, I encourage anyone to read King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce, published by Media History Press. Also read this by Cartoon Research columnist James Parten.

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Tom Klein is a Professor and the Chair of the Animation program at Loyola Marymount University, in Los Angeles. He has been published internationally and has been profiled in The New York Times for his work as a scholar of the Walter Lantz studio. He has worked at Vivendi-Universal Games and Universal Cartoon Studios. Follow him @VizLogic

Thank you. I look forward to seeing the film.

All Quiet on the Western Front was the other big 1930 Universal feature production. Its huge success covered the losses incurred by King of Jazz.

Yes, that’s certainly true, Harvey, and only more so in retrospect: by the end of 1930, All Quiet had won the Academy Award for Best Picture (“Outstanding Production” it was known then) and was the huge sleeper hit of the year for Universal. King of Jazz was a case of underperforming vs. its outsized expectations, needing to justify its massive budget and hype. Eventually, Laemmle did recoup his investment. More recently, the film has gotten more attention again, both as a result of its 2013 induction into the National Film Registry and this recent restoration by Universal.

I just saw this at the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, and boy is it a weird film. The Rhythm Boys (featuring Bing Crosby) are great, but the comedy bits are groaners and most of the music pieces go on way too long. Still, the art direction including the big piano is impressive.

Of course, they could’ve solved the color problem by painting the red parts, then painting over them with a second layer of white, which wouldn’t flake and was proven opaque. Hey, I shoulda been there.

Steve, I think King of Jazz can be surprising, even oddball, because of the eclectic blend of its comedy and musical revue format with a handful of courtly set pieces. Mixing in the timeless vignettes among the dated ones, and of course there are certain things that reflect and don’t transcend its time, the impression is still indelible. It’s an over-the-top, eye-candy time capsule with cinema history significance. From my perspective writing about Oswald, it’s interesting how watching King of Jazz has the same tone as watching the 1930-31 cartoon series: many of the same songs, eccentric in parts (remember Fowl Ball?) and light and comedic. The feature has its own spoof of All Quiet titled “All Noisy on the Eastern Front.” Sure enough, there’s an entire Oswald cartoon spoof, too: “Not So Quiet”

The insight about the red paint is very intriguing, I think it’s a great example of how technological constraints can drive creative output. Thank you for the brilliant article!