Suspended Animation #350

In the 1930s, Walt Disney was interested in two French properties, Reynard the Fox and Chanticleer but both presented story challenges because of generally unsympathetic main characters.

Chanticleer was a 1910 play by Edmond Rostand who also wrote Cyrano de Bergerac and Walt initially liked the idea of doing a big barnyard comedy with a cast of pretentious roosters and chickens in fancy feathers with lots of sight gags perhaps as a reminder of his Silly Symphonies series.

Chanticleer was a 1910 play by Edmond Rostand who also wrote Cyrano de Bergerac and Walt initially liked the idea of doing a big barnyard comedy with a cast of pretentious roosters and chickens in fancy feathers with lots of sight gags perhaps as a reminder of his Silly Symphonies series.

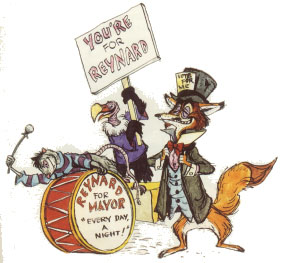

Reynard is a group of French, Dutch and German fables, novels and poems by multiple authors (the most well known version is by Goethe) collected around the eleventh century. They were used as moral tales for children and parodies of medieval literature as well as biting political satire for adults.

Reynard was put into development as a possible animated feature film as early as 1937. Another appealing aspect for Walt was that the Reynard stories were in public domain so he would not have to pay any royalties.

Walt assigned his story people Dorothy Blank (who had worked on Snow White) and Al Perkins to come up with a treatment that adhered closely to the original story.

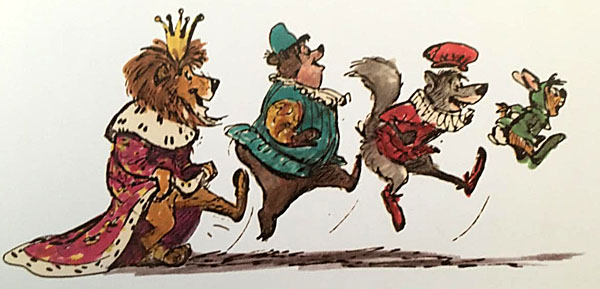

After deceptions, disguises, and last minute escapes, Reynard is eventually captured and brought to the King who sentences him to be hanged for his many crimes.

After deceptions, disguises, and last minute escapes, Reynard is eventually captured and brought to the King who sentences him to be hanged for his many crimes.

At the end, on the gallows, Reynard confesses that his father once tried to overthrow the King….with the help of the Wolf. The Wolf is imprisoned and Reynard spins a tale of his father’s vast wealth hidden in a volcano.

When the King and his subjects go to the volcano, it explodes and many are killed but the King escapes. The King frees the Wolf who challenges Reynard to a duel that the fox wins through trickery and demands a royal ball be thrown in his honor. As everyone is celebrating, he steals the royal treasury.

When captured, he begs not to be banished to the volcano very much like B’rer Rabbit pleading not to be thrown in the briar patch. Once he is exiled to the volcano, Reynard looks down on the village with a sly smile and digs up all the treasure.

In a meeting at the Disney Studio on February 12, 1938 that included story people like Bill Cottrell, Ben Sharpsteen and Otto Englander, Walt raised some concerns.

“I see some swell possibilities in Reynard but is it smart to make it?” asked Walt. “Our main character is a crook, and there’s nothing about him having a ‘Robin Hood’ angle. We have such a terrific kid audience…parents and kids together. That’s the trouble. It’s too sophisticated. He’s not to be a murderer under any circumstances. He shouldn’t take advantage of anybody but a stupid individual.”

In one early treatment, Reynard steals all the King’s rings by kissing his hand, a gag that would be later done in Robin Hood (1973).

Walt said, “The Hays Office is down on glorifying crooks because of churches and so on. They have a terrific influence. Even Cock Robin (the 1935 Silly Symphony Who Killed Cock Robin?) ran into things all over. We got letters from all over. A lot of people don’t think that’s the right kind of thing we should do….trying to be too smart.”

Walt said, “The Hays Office is down on glorifying crooks because of churches and so on. They have a terrific influence. Even Cock Robin (the 1935 Silly Symphony Who Killed Cock Robin?) ran into things all over. We got letters from all over. A lot of people don’t think that’s the right kind of thing we should do….trying to be too smart.”

In May 1941, Walt purchased the rights to Rostand’s Chanticleer for $5,000 and assigned story people Ted Sears and Al Perkins to develop a treatment.

In 1945, writer Clifton Johnson tackled a treatment of Reynard where Reynard causes the Cat to lose an eye, eats the Hare and tricks the Ram into taking the Hare’s head back to the King in a bag under the assumption that it is the treasure. Through his trickery, Reynard ends up High Chancellor to the King.

In 1947, three different treatments were prepared. By then, the Disney Studio Library had amassed a large collection of different versions of the story. Walt himself checked out a copy of Rogue Reynard by Andre Norton.

The first treatment is dated January 28th, 1947. It was hoped to get French actor Charles Boyer as the narrator or someone similar in tone. The King is now a comedic figure, constantly combing his mane while admiring himself in a hand mirror.

The first treatment is dated January 28th, 1947. It was hoped to get French actor Charles Boyer as the narrator or someone similar in tone. The King is now a comedic figure, constantly combing his mane while admiring himself in a hand mirror.

Now the story revolves around the Wolf, Bear and Cat in some sort of conspiracy plot against the King, primarily an attempt to steal the King’s treasure. The Wolf tells the King of the many complaints against Reynard and the King sends the Bear who is depicted as slow-witted and a bit of a bumbler just like B’rer Bear.

Reynard is not depicted as a scoundrel but as a “free spirit” who enjoys having fun at other people’s expense. He easily tricks the Bear into getting stung searching for honey. Then the fox disguises himself as a woman and flirts with the bear only to sneak out of a bear hug and reappear as himself shouting the accusation, “My wife!” and pummels the Bear with a club in a scene that is actually more amusing than violent.

The Wolf tells the King that only the royal lion himself is smart enough to capture the fox. In actuality, the Wolf and his compatriots plan to kill the King and blame it on Reynard. Flattered, the King accepts the challenge and disguises himself. However, when he arrives at Reynard’s, he is indeed attacked by the three villains but is rescued by Reynard.

However, because of the confusion, Reynard is falsely accused of leading the attack. On the gallows, he is able to clear himself of all charges and prove the guilt of the three villains.

The next two 1947 versions are from animator Norm Ferguson, famous for his work on the character of Pluto among other accomplishments. It is apparent that Ferguson did not use any of the original source material or the books in the studio library but based his version on the first 1947 version where the Wolf, Bear and Cat are in league against the King.

In his first treatment, Ferguson focuses on a series of mysterious crimes that have taken place and an initialed handkerchief with an “R” on it always left at each scene. Of course, the assumption is that it is Reynard who fails to show up for his court appearance and is defended by his friend, a badger.

In his first treatment, Ferguson focuses on a series of mysterious crimes that have taken place and an initialed handkerchief with an “R” on it always left at each scene. Of course, the assumption is that it is Reynard who fails to show up for his court appearance and is defended by his friend, a badger.

Paralleling this action is another court in session with small animals in a large cavern. This court is addressed by Reynard who tells his subjects that he is aware of the crimes and vows to uncover the real perpetrator. A song, It’s Reynard, is sung by his subjects.

The story is filled with accusations, disguises, Reynard always barely escaping capture and finally him using the promise of treasure to reveal the true conspirators.

In his second treatment, Ferguson emphasizes more humor and relies on flashbacks. In fact, the film starts with Reynard on the gallows with the Wolf listing in great deal the crimes Reynard has done.

In his second treatment, Ferguson emphasizes more humor and relies on flashbacks. In fact, the film starts with Reynard on the gallows with the Wolf listing in great deal the crimes Reynard has done.

Reynard applauds after the Wolf’s presentation and adjusting the noose around his neck like a tie, proceeds to tell the real truth behind all the accusations, including how the Wolf, Bear, Cat, Ram and Hare failed to bring back the treasure. He reveals the conspiracy between these animals.

Reynard is so convincing that the King and the crowd decide to free Reynard and hang the other animals. Ferguson depicts Reynard as an “English gentleman” and includes a song We’re Hanging Reynard Today.

In fact, animator Frank Thomas told writer and historian John Cawley that three films were under serious consideration for the next animated feature: Alice in Wonderland, Cinderella and Reynard. Cinderella was chosen with Alice a close second.

Next Week: The Ken Anderson and Marc Davis 1960 musical version and Reynard in Treasure Island (1950).

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

I would love to have seen Disney make a Reynard/Chanticleer animated feature. I realize a lot of the character designs by Ken Anderson were used for Robin Hood (a movie I love), but it still would have been nice if Disney had made a Reynard movie back then.

I first became acquainted with the Reynard fables through Igor Stravinsky’s 1916 ballet “Renard” (Reynard is part of Russian folklore, too). I’ve never heard it in concert or seen it staged, but when I first heard a recording of it at age 15, I thought it would have been well suited to animation. Like many Golden Age cartoons, it’s scored for a small orchestra with a male vocal quartet; come to think of it, the ensemble is almost exactly the same as the one Winston Sharples used in “The Sunshine Makers”, though with a cimbalom (that is, a Hungarian hammer dulcimer) instead of a piano. As in many cartoon scores, the singers in “Renard” are part of the orchestra and do not correspond directly to the characters in the ballet. The second bass part is in an extremely low register and seems to have been made to order for Thurl Ravenscroft.

But as Walt Disney surmised, the Hays Office would have objected to much in the ballet, especially its lampooning of religion. Renard enters dressed as a monk, calling out to the rooster to come down from his perch and confess his sins, making him feel guilty because he has a harem of many hens. When the rooster finally comes down and begs forgiveness, the fox grabs him. Now that’s a gag I’d have loved to see in a Baby Huey cartoon.

Walt Disney hosted a program for the anthology series titled “From Aesop to Hans Christian Andersen: in which he spotlights folk tales through the ages. He makes prominent mention of the tales of Reynard the Fox, and some of the sketches shown bear a resemblance stylistically to those shown above. Possibly one of the few public references that Disney made to the tales of Reynard the Fox.

He also made mention of Chanticleer as a way of introducing the short “Barnyard Symphony”. The clip is an Easter egg on the Walt Disney Treasures Silly Symphonies tin.

Wondering now if any bits of Reynard and/or Chanticleer figured in the making of the wartime short “Chicken Little”.

It’s a shame that Disney never made any movie based on Reynard or Chanticleer. I think they would’ve been fine funny animal vehicles. Besides, the massive success of Zootopia proved that audience will readily flock to such a movie. That being the case, both The Little Mermaid and Beauty and the Beast were brainstormed during Walt’s lifetime, but didn’t make it out as actual features until the Disney Renaissance. Who’s to say the same can’t happen with these projects?

At the very least, those interested in an animated Reynard can watch Ladislas Starevich’s earlier stop motion feature (the poster of which can be seen in this post). The guy was a master of animation, and I highly recommend watching at least some of his work (I myself like to point to The Cameraman’s Revenge). As for Chanticleer, as we all know, Don Bluth took the idea with him and made it as 1992’s Rock-a-Doodle, but the less said about that, the better.

Reminded Germany and China co-produced an adaptation of Reynard the Fox in the 80’s.

https://youtu.be/r2VRswWnRdY

Our beloved friend Robie Lester always regretted that this film was not made because she was to play a significant role in the voice cast.

I’m kind of under the impression that Marc Davis’ designs for the proposed ’60’s version were later used as the basis for his 1974 Disneyland attraction, “America Sings”.

Yes, some of the designs were later adapted by Davis for the America Sings attraction…..especially the chicken characters. Many of these audio-animatronics were then later moved to Splash Mountain after America Sings closed. And, of course, both Davis and Ken Anderson character designs were adapted fro the Disney animated feature, ROBIN HOOD.