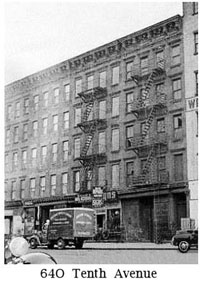

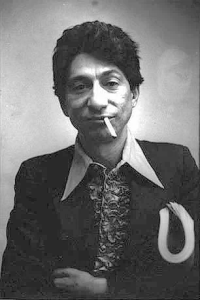

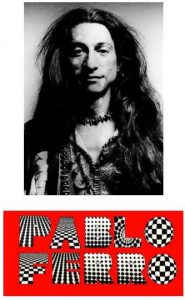

It may have been evident back around 1946 that the tiny port city of Antilla, Cuba was not big enough to contain Pablo Ferro. Anyways, his politically outspoken father fled to New York City when Pablo was eleven and the family followed. The boy spoke no English. They settled into Hell’s Kitchen at 640 Tenth Avenue. When Pablo was fourteen his brutish, womanizing father abandoned them, so the young man got a job to help out. Many people in his tenement building eked out a living assembling piano parts at the factory right next door, but Pablo wandered over to the Times Square district in search of something more suited to his creative temperament.

It may have been evident back around 1946 that the tiny port city of Antilla, Cuba was not big enough to contain Pablo Ferro. Anyways, his politically outspoken father fled to New York City when Pablo was eleven and the family followed. The boy spoke no English. They settled into Hell’s Kitchen at 640 Tenth Avenue. When Pablo was fourteen his brutish, womanizing father abandoned them, so the young man got a job to help out. Many people in his tenement building eked out a living assembling piano parts at the factory right next door, but Pablo wandered over to the Times Square district in search of something more suited to his creative temperament.

Pablo’s artistic talent brought him to the High School of Industrial Arts, where he met Phil Kimmelman. While Pablo adapted to speaking English, Phil let Pablo copy his school work. One teacher who caught on to this failed Phil and passed Pablo. Phil didn’t care. He and Pablo were loyal. They became friends with Dante Barbetta and all learned how to animate from Preston Blair’s book. Pablo didn’t always talk much, often he was too busy turning cartwheels or doing handsprings, off across the park, or through a school hallway . . . Pablo rolled onward.

Pablo’s artistic talent brought him to the High School of Industrial Arts, where he met Phil Kimmelman. While Pablo adapted to speaking English, Phil let Pablo copy his school work. One teacher who caught on to this failed Phil and passed Pablo. Phil didn’t care. He and Pablo were loyal. They became friends with Dante Barbetta and all learned how to animate from Preston Blair’s book. Pablo didn’t always talk much, often he was too busy turning cartwheels or doing handsprings, off across the park, or through a school hallway . . . Pablo rolled onward.

After school Pablo worked as an usher atthe Apollo Thearter oh 42nd Street, directly across from the Candler Building. The Apollo screened foreign language movies. One benefit of this job was the opportunity to learn about film editing with the splicer in the screening room. Another was that the manager sometimes paid Pablo extra to design advertising art for the lobby and box office. It did help with ticket sales, affording Pablo an up-close view of consumers’ tastes. Multiple viewings of cinema from around the world expanded Pablo’s cinematic vocabulary. During off hours he palled around with Phil and Dante.

After school Pablo worked as an usher atthe Apollo Thearter oh 42nd Street, directly across from the Candler Building. The Apollo screened foreign language movies. One benefit of this job was the opportunity to learn about film editing with the splicer in the screening room. Another was that the manager sometimes paid Pablo extra to design advertising art for the lobby and box office. It did help with ticket sales, affording Pablo an up-close view of consumers’ tastes. Multiple viewings of cinema from around the world expanded Pablo’s cinematic vocabulary. During off hours he palled around with Phil and Dante.

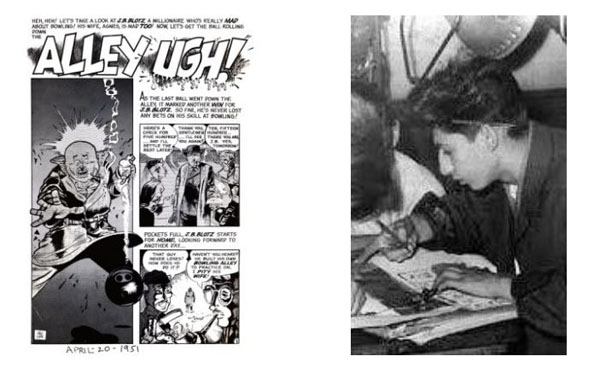

At this time Pablo decided he would be a comic book artist and hammered out a four page story titled ALLEY-UGH! He worked on it as part of his art class at school. One day the teacher launched into a stern lecture ridiculing Pablo’s ambitions. This teacher mocked the idea that anyone would just draw a story and then try to sell it without a prior contract. He pontificated that the business simply did not function In such a way, and that Pablo was wasting his time. Pablo’s response came a few weeks later when he sold the story to Stan Lee at Atlas Comics.

At this time Pablo decided he would be a comic book artist and hammered out a four page story titled ALLEY-UGH! He worked on it as part of his art class at school. One day the teacher launched into a stern lecture ridiculing Pablo’s ambitions. This teacher mocked the idea that anyone would just draw a story and then try to sell it without a prior contract. He pontificated that the business simply did not function In such a way, and that Pablo was wasting his time. Pablo’s response came a few weeks later when he sold the story to Stan Lee at Atlas Comics.

Stan Lee told Pablo to bring him any more stories, and there were a couple. Money from those comic books helped finance the Brooklyn studio Pablo ran with Phil and Dante. When Phil and Pablo brought some neighborhood girls in to see the studio they caught an earful from Dante about how they were there to work, not flirt. Before graduation arrived Pablo Ferro quit school, concentrating on securing employment animating television commercials. Using his comic book pages as a portfolio, he impressed designer Ray Favata at Tempo Productions enough to get a foot in the door as an office boy/inker during the summer of 1953.

This percolating bundle of creative energy fit right in, and he was in a room full of heavy hitters. Tempo Productions owner Dave Hilberman had animated on several Disney classics.

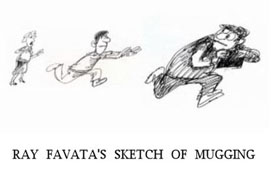

Hilberman’s old Disney supervisor Bill Tytla headed Tempo’s animation department. Bernice Rankin and Ray Favata, both accomplished designers, brought a contemporary feel to each commercial. When Abe Liss resigned the top spot at UPA’s New York branch he went to Tempo. Pablo watched everything everybody did there, bombarding Bill Tytla with questions. Tytla answered each one patiently. After eight months Pablo was promoted to inbetweener, but still accompanied the secretary to the bank every payroll day. One time a mugger snatched the secretary’s purse. Pablo tackled the thief and held him until police arrived.

Hilberman’s old Disney supervisor Bill Tytla headed Tempo’s animation department. Bernice Rankin and Ray Favata, both accomplished designers, brought a contemporary feel to each commercial. When Abe Liss resigned the top spot at UPA’s New York branch he went to Tempo. Pablo watched everything everybody did there, bombarding Bill Tytla with questions. Tytla answered each one patiently. After eight months Pablo was promoted to inbetweener, but still accompanied the secretary to the bank every payroll day. One time a mugger snatched the secretary’s purse. Pablo tackled the thief and held him until police arrived.

He was very much that street-wise kid from Hell’s Kitchen, now immersed in a business where millions of dollars changed hands between large corporations and a bunch of artist/film makers. Pablo socialized among the animation community, taking a penthouse at West End Avenue and 93rd Street. He traded in his rumpled army jacket for a conservative suit. He stopped turning cartwheels in the hallway.

Tempo Productions became Academy Pictures in 1954. Vince Cafarelli showed up that summer. Cafarelli, only a bit older than Ferro, had started out inbetweening at Famous Studios, worked for Bill Sturm, spent his Army enlistment drawing instruction manuals for the Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, then joined Film Graphics. Vince Cafarelli and Pablo Ferro became fast friends at Academy Pictures.

Having achieved the status of full-fledged animator, Pablo entered his third year with the studio. He spent November of 1955 vacationing in Hollywood, poking around the scene and making connections. Early in 1956 Vince Cafarelli introduced Pablo to Fred Mogubgub. Pablo arranged for Academy to hire Mogubgub as his assistant. When Tempo first transitioned into Academy Productions the shop retained that Tempo magic – for a while, at least. Dave Hilberman, the real heart and soul of the place, was gone. Also, Abe Liss had moved on to form Elektra Films, the hip new studio that ad agencies were buzzing about. Pablo made the jump from Academy to Elektra.

Having achieved the status of full-fledged animator, Pablo entered his third year with the studio. He spent November of 1955 vacationing in Hollywood, poking around the scene and making connections. Early in 1956 Vince Cafarelli introduced Pablo to Fred Mogubgub. Pablo arranged for Academy to hire Mogubgub as his assistant. When Tempo first transitioned into Academy Productions the shop retained that Tempo magic – for a while, at least. Dave Hilberman, the real heart and soul of the place, was gone. Also, Abe Liss had moved on to form Elektra Films, the hip new studio that ad agencies were buzzing about. Pablo made the jump from Academy to Elektra.

Abe Liss was a huge influence on Pablo Ferro. Liss pushed the boundaries of emerging technology in tandem with refined artistic insights. Elektra Films’ teleblurbs hawked any product a wealthy corporation or organization was able to spend big dollars promoting. Elektra’s editing and optics equipment were state-of-the art. Abe Liss had handed Pablo Ferro a box full of shiny new toys.

In the summer of 1957 Pablo Ferro became a Naturalized United States citizen. TOP CEL editor Ed Smith joked that this tilted the balance of power in the Cold War. Ed Smith knew Pablo well enough through the union, due to Pablo being a delegate from Elektra. Beyond that, Ed Smith had worked with Vince Cafarelli and Fred Mogubgub before Pablo met any of them.

Vince and Fred were still at Academy Pictures, and that place was on its way out. An artist picking the right studio was a lot like a surfer choosing the right wave. How far could it carry you before petering out? And would it leave you in position to catch the next wave? Thirteen years ago Pablo had stepped off a boat into New York City. A mere five years ago this television advertisement business he made such good money at was still a vague concept.

Pablo, now a U.S. Citizen, visited Cuba with Phil Kimmelman. They witnessed the fall of Havana to Fidel Castro’s forces. When they got home an opportunity presented itself to Pablo. The comedy team Bob & Ray were starting a production company with an animation division run by a former employee of J. Walter Thompson, the largest ad agency in America. Pablo was offered the job of animation supervisor. He took the leap, hiring Vince Cafarelli, Fred Mogubgub, Phil Kimmelman, and Al Eugster as his crew.

They made commercials and special projects for Bob & Ray. Phil got drafted into the Army in the middle of working on the twenty minute long cartoon TEST DIVE BUDDIES. Vince Cafarelli was Pablo’s wing-man on a journey to Cuba in early 1959. They hung around the New York animation scene together. Pablo’s friend from high school, Agnes Hazel Allen, worked at Robert Lawrence Productions, where she’d married designer George Cannata Jr. This guy Cannsta had a sister named Dolores, a designer/animator working on both coasts. Dolores Cannata drove a motorcycle. Pablo nursed a crush on her, but his heart truly belonged to a friend of Agnes named Susan.

They made commercials and special projects for Bob & Ray. Phil got drafted into the Army in the middle of working on the twenty minute long cartoon TEST DIVE BUDDIES. Vince Cafarelli was Pablo’s wing-man on a journey to Cuba in early 1959. They hung around the New York animation scene together. Pablo’s friend from high school, Agnes Hazel Allen, worked at Robert Lawrence Productions, where she’d married designer George Cannata Jr. This guy Cannsta had a sister named Dolores, a designer/animator working on both coasts. Dolores Cannata drove a motorcycle. Pablo nursed a crush on her, but his heart truly belonged to a friend of Agnes named Susan.

Because Susan was married, Pablo would not express his deep feelings for her, his Muse. Pablo became close friends with Susan. She was in the room one night when Pablo engaged in a debate with George Cannata Jr. about the potential and limits of new editing equipment. Pablo claimed it allowed for a revolutionary style of quick-cut splicing. George vehemently disagreed. Good times.

Being secretly in love with Susan proved distracting. When Susan announced she and her husband were expecting a baby, Pablo decided to distance himself. Abe Liss was trying to entice him back to Elektra Films. George and Dolores Cannata had both signed on there. Susan called Pablo out of the blue. She needed someone to accompany her to Mexico where she could obtain a divorce. During the trip Pablo declared his feelings. They married before returning home. Pablo adopted Susan’s son Allen.

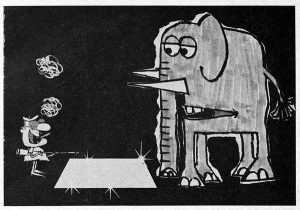

Abe Liss sweetened the pot, so Pablo returned to Elektra. Working jointly with Jack Goodford supervises the TV commercial department. Goodford handled live-action spots while Pablo oversaw animated ads. Pablo brought in Fred Mogubgub as his assistant, and threw some work to Phil Kimmelman, who was stationed at West Point. Elektra Films represented the modern, using a paper-cut elephant named Sweetie Baby in a series of floor tile commercials for Sanduran. The ads were based on designs by Len Glasser, art director for the agency Hicks & Geist. Pablo directed them.

Abe Liss sweetened the pot, so Pablo returned to Elektra. Working jointly with Jack Goodford supervises the TV commercial department. Goodford handled live-action spots while Pablo oversaw animated ads. Pablo brought in Fred Mogubgub as his assistant, and threw some work to Phil Kimmelman, who was stationed at West Point. Elektra Films represented the modern, using a paper-cut elephant named Sweetie Baby in a series of floor tile commercials for Sanduran. The ads were based on designs by Len Glasser, art director for the agency Hicks & Geist. Pablo directed them.

Liss put Ferro’s intense focus to good use on a particularly complex assignment in 1960, a color animation of the NBC Peacock logo, done in collaboration with genius designer Saul Bass.

Liss put Ferro’s intense focus to good use on a particularly complex assignment in 1960, a color animation of the NBC Peacock logo, done in collaboration with genius designer Saul Bass.

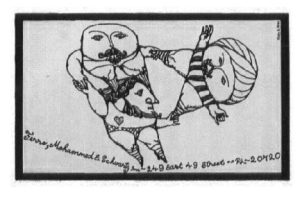

Jack Goodford had supervised animation at UPA, and often encroached on Pablo’s territory. Pablo brought Phil Kimmelman into the department when Phil left the Army at the end of 1960. Pablo groomed Phil to take his place at Elektra. In May of 1961 Pablo Ferro and Fred Mogugub partnered in a new studio, calling themselves “visual communicators”. They rented three floors of a renovated brownstone at 249 East 49th Street. Because he spent so much time at work, Susan designed a bed that came down from the wall of Pablo’s office using a piano hinge.

Ferro, Mogubgub and Schwartz Incorporated included Lewis Schwartz, who started out as a comic strip artist before being supervisor in charge of commercial animated film production at J. Walter Thompson. Schwartz left JWT to produce teleblurbs with Phil Kimmelman’s buddies Ron Fritz and Dan Hunn. Ferro and Mogubgub hired Schwartz away.

A wide range of services were available at Ferro, Mogubgub and Schwartz, from simply acting as film consultants to full production of commercials and industrial films. They started out with a dozen artists on staff. Pablo proved George Cannata wrong about that quick-cut editing style by displaying hundreds of images in twenty second with an ad for Hartford, Connecticut’s Channel WHCT. Breaking through mediums, FM&S provided animated sequences for Jerome Robbins’ stage play OH DAD, POOR DAD, MAMMA’S HUNG YOU IN THE CLOSET AND I’M FEELING SO SAD. Off beat TV ads for Coca Cola, Ford Motors, Dixie Cups, Brillo, Amoco Gasoline, Arrestin Cough Syrup, Post Cereals, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Westinghouse, Nabisco, Salada Tea, Marathon Oil. and U.S. Steel rolled out of FM&S.

A wide range of services were available at Ferro, Mogubgub and Schwartz, from simply acting as film consultants to full production of commercials and industrial films. They started out with a dozen artists on staff. Pablo proved George Cannata wrong about that quick-cut editing style by displaying hundreds of images in twenty second with an ad for Hartford, Connecticut’s Channel WHCT. Breaking through mediums, FM&S provided animated sequences for Jerome Robbins’ stage play OH DAD, POOR DAD, MAMMA’S HUNG YOU IN THE CLOSET AND I’M FEELING SO SAD. Off beat TV ads for Coca Cola, Ford Motors, Dixie Cups, Brillo, Amoco Gasoline, Arrestin Cough Syrup, Post Cereals, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Westinghouse, Nabisco, Salada Tea, Marathon Oil. and U.S. Steel rolled out of FM&S.

One of those ads that aired in Britain caught the attention of brilliant movie director Stanley KubricK. Titles and coming attraction trailers were needed for Kubrick’s film DR. STRANGELOVE: OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE BOMB. Kubrick set Pablo and Susan up in a London flat. The couple explored the countryside, sometimes crossing the Channel to Amsterdam where smoking weed was legal. Kubrick would drop by the flat and ounce ideas about the movie around with Pablo.

Kubrick and Ferro wanted to represent the sexuality of machines, using footage of a bomber plane refueling in flight. Large, thin hand-drawn titles filled the screen in a most unusual manner. While in England, Ferro also did titles for Gina Lollabrigida’s movie WOMAN OF STRAW. He created commercials for British television, one of which won an award.

The New York office of FM&S fell into chaos with Pablo’s absence. Fred Mogubgub was a great artist, but no businessman. What the Hell was Lew Schwartz doing? Pablo sent money home. Vince Cafarelli remained on the scene, moving between New York and London. In September of 1962 Fred Mogubgub split to start his own studio. Ferro and Schwartz responded by hosting a contest for someone from the ad agencies to come up with a three syllable name beginning with the letter M. Some guy at Benton and Bowles proposed Mohammed.

Ferro’s BeechNut Fruit Sours commercial experimented with split-screen techniques, showing more than one image at a time. He did a spot for NBC promoting their Huntley & Brinkley newscasts. The advertisement industry’s Clio Awards ceremony for 1963 ran a film by Pablo Ferro highlighting new special effects made possible by rapidly advancing technology. The Ferros were back in New York by the start of 1964, moving into another penthouse, along Central Park West around 94th Street. The building had a doorman.

DR. STRANGELOVE garnered rave reviews, being nominated in four Oscar categories. Pablo Ferro’s theatrical trailer received nearly as much praise as the movie itself. He continued experimenting with multiple imagery, using projectors for a sequence on the ED SULLIVAN SHOW, and the World’s Fair pavilion of Singer Industries. Ferro, Mohammed & Schwartz powered on. Warner Brothers hired FM&S to create the TV promos for their film SEX AND THE SINGLE GIRL. Tension developed between Ferro and Schwartz. Vince Cafarelli went over to Len Glasser’s studio Stars and Stripes Productions Forever. Pablo started afresh in July of 1964 as Pablo Ferro Films in the Hearn Building at 45 West 45th Street.

New York based Blue Sky Productions asked Pablo to direct their feature film DR. ROCK AND MR. ROLL. Basil Rathbone and Huntz Hall, both once big stars at Warner Brothers, were signed on. Allied Artists was slated to distribute. Rathbone would play right-wing Dr. Rock, who turned into the diabolical Mr. Roll whenever he heard Rock & Roll music. Sonny & Cher were in talks to appear when financing fell through.

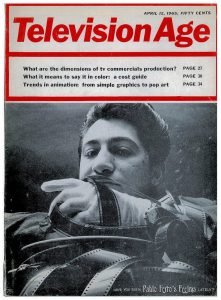

Different, sometimes conflicting, worlds tugged at Pablo Ferro. Hollywood executives knew his name. Broadway actors broke bread with him. Greenwich Village Bohemians embraced him as one of their own. TELEVISION AGE Magazine featured Pablo on a cover. The cream of Madison Avenue’s ad men courted his services for an elite clientele: DuPont; Shell Oil; Standard Oil; The East Ohio Gas Co.; First Pennsylvania Banking & Trust Co.; Florida Citrus Commission; Ford Motors; General Motors; B. F. Goodrich Tires; The New York Times; Pepsi; NBC; RCA; General Foods Corp. With varying degrees of success Pablo was an artist, and a businessman, and a husband, and a father . . . again, when Susan delivered their daughter Joy in December of 1965.

Different, sometimes conflicting, worlds tugged at Pablo Ferro. Hollywood executives knew his name. Broadway actors broke bread with him. Greenwich Village Bohemians embraced him as one of their own. TELEVISION AGE Magazine featured Pablo on a cover. The cream of Madison Avenue’s ad men courted his services for an elite clientele: DuPont; Shell Oil; Standard Oil; The East Ohio Gas Co.; First Pennsylvania Banking & Trust Co.; Florida Citrus Commission; Ford Motors; General Motors; B. F. Goodrich Tires; The New York Times; Pepsi; NBC; RCA; General Foods Corp. With varying degrees of success Pablo was an artist, and a businessman, and a husband, and a father . . . again, when Susan delivered their daughter Joy in December of 1965.

People called Pablo Ferro a genius as his public persona gained attention. He’d broken beyond animation into the realm of mainstream cinema. And yet, there was a secret personal life weighing upon him. Pablo had smoked marijuana since high school. Harder substances were available on the New York art scene, and he experimented with LSD.

People called Pablo Ferro a genius as his public persona gained attention. He’d broken beyond animation into the realm of mainstream cinema. And yet, there was a secret personal life weighing upon him. Pablo had smoked marijuana since high school. Harder substances were available on the New York art scene, and he experimented with LSD.

The 1960s were a decade of sexual awareness. In tandem with increased drug use, Pablo joined the swingers, often having sex with more than one partner at a time. Guilt about his covert carnality may have plagued him. Right after Joy’s birth Pablo came clean to Susan, about his lustful adventuring. He wondered if it was a journey she might be interested in joining him on. Susan told Pablo he must move out. She still loved him, but he needed to move out.

Arnie Levin, one of the animators freelancing for Pablo, knew about a loft available in Greenwich Village at 201 Second Avenue, between 12th and 13th Streets. Pablo Ferro Films opened a branch office in Chicago. He spent some time in Hollywood designing the opening titles for director Norman Jewison’s movie THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING, animating a struggle for dominance between a United States flag and a Soviet Union flag to the tune of YANKEE DOODLE. Pablo bonded with Hal Ashby, the movie’s editor. Hal Ashby was plugged into actor Jack Nicholson’s crowd, and members of that clique visiting New York partied at Pablo’s loft above the Chinese restaurant.

Arnie Levin, one of the animators freelancing for Pablo, knew about a loft available in Greenwich Village at 201 Second Avenue, between 12th and 13th Streets. Pablo Ferro Films opened a branch office in Chicago. He spent some time in Hollywood designing the opening titles for director Norman Jewison’s movie THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING, animating a struggle for dominance between a United States flag and a Soviet Union flag to the tune of YANKEE DOODLE. Pablo bonded with Hal Ashby, the movie’s editor. Hal Ashby was plugged into actor Jack Nicholson’s crowd, and members of that clique visiting New York partied at Pablo’s loft above the Chinese restaurant.

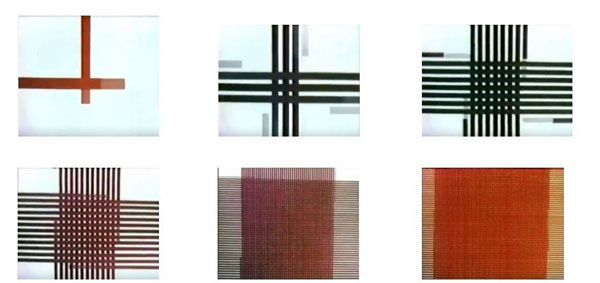

Day to day work at 45 West 45th Street was handled by Arnie Levin, Jack Dazzo and whatever other freelancers were on hand. The grunt work fell to Pablo’s brother Jose. Pablo got in the habit of rolling through the door late in the afternoon, but always ready to put in a full shift. The problem being that everyone else was exhausted by that point. He stepped up to the plate and hit a homerun when animating the Burlington Mills weave logo. That spot aired for years.

The Hippy movement came into full bloom in mid-1967, the Summer of Love. Pablo was kicking around Europe at the time. Editor Hal Ashby needed to pick up the pacing for Norman Jewison’s latest film THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR, concerning a sophisticated game of cat-and-mouse between millionaire bank robber Steve McQueen and clever insurance investigator Faye Dunway. That multiple-screen effect would fit perfectly here, but how to pull it off still eluded Pablo. Undaunted, Ferro and Ashby borrowed a special lens from the Disney studio and went to work on the optical printers.

Ferro had already achieved results where several elements from a story could be viewed simultaneously. The effect was in use to some extent, notably in the opening credits of the TV show MANNIX. Ferro and Ashby took it farther, compositing as many as sixty separate images onto the screen at once. They enhanced the face of cinema.

Steve McQueen gave Pablo carte blanche on the titles for the police themed BULLITT in 1968. Pablo used zoom lenses on still photos, contrasting black and white Ben Day dots against each other to great graphic effect. Producer Norman Lear shot THE NIGHT THEY RAIDED MINSKY’S, his tribute to burlesque, in the neighborhood around Pablo’s loft. Pablo did the titles for that film and later assisted with editing. His screen credit reads: VISUAL CONSULTANT AND SECOND UNIT DIRECTOR. What he actually did was salvage the film in post production.

MIDNIGHT COWBOY, with opening titles by Pablo Ferro, collected three 1969 Oscars including Best Picture. Pablo also performed the duties of a second unit director on that movie. The Sony Corporation marketed reusable videotape as an alternative to the high cost of film stock and processing. Pablo disliked the bulkiness of the videotape equipment, and that it’s high resolution diminished the surrealness of a movie. Regardless of this, Pablo accepted some videotape equipment from Sony to use as part of their research and development.

MIDNIGHT COWBOY, with opening titles by Pablo Ferro, collected three 1969 Oscars including Best Picture. Pablo also performed the duties of a second unit director on that movie. The Sony Corporation marketed reusable videotape as an alternative to the high cost of film stock and processing. Pablo disliked the bulkiness of the videotape equipment, and that it’s high resolution diminished the surrealness of a movie. Regardless of this, Pablo accepted some videotape equipment from Sony to use as part of their research and development.

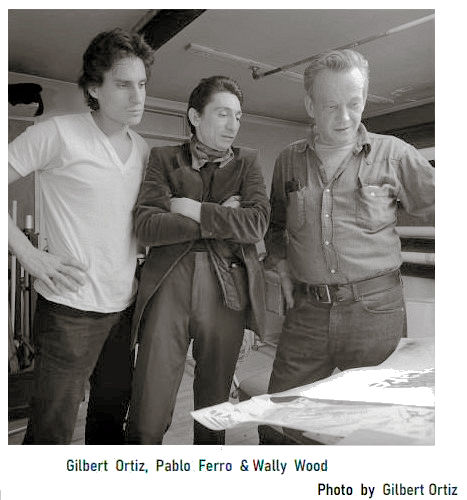

New York contained a vibrant indie film scene, with Robert Downey Sr. at the forefront. Pablo appeared in some of Downey’s experimental shorts, and made a few of his own with the video=tape equipment. Vince Cafarelli acted in THE INFLATABLE DOLL. Parties at the loft went on for days. Big name celebrities frequented these bacchanals. Yoko Ono might drop in and turn on. Andy Warhol’s entourage made the scene. Actor Sal Mineo was a regular. Pablo Photographer Gilbert Ortiz rented a room there for a while. When Pablo screened THE INFLATABLE DOLL Robert Downey Sr. declared it to be the strangest love story he’d ever seen. Ringo Starr’s review was “Yes!?!”. Harry Nilsson said he had to agree with Ringo.

New York contained a vibrant indie film scene, with Robert Downey Sr. at the forefront. Pablo appeared in some of Downey’s experimental shorts, and made a few of his own with the video=tape equipment. Vince Cafarelli acted in THE INFLATABLE DOLL. Parties at the loft went on for days. Big name celebrities frequented these bacchanals. Yoko Ono might drop in and turn on. Andy Warhol’s entourage made the scene. Actor Sal Mineo was a regular. Pablo Photographer Gilbert Ortiz rented a room there for a while. When Pablo screened THE INFLATABLE DOLL Robert Downey Sr. declared it to be the strangest love story he’d ever seen. Ringo Starr’s review was “Yes!?!”. Harry Nilsson said he had to agree with Ringo.

A mixed bag of activists and radicals passed through, but it was never political at Pablo’s loft, jus pure, stress-relieving hedonism. When the crowd dispersed he worked.

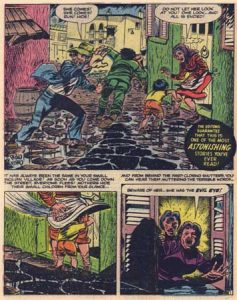

Comic book master Wally Wood illustrated for Pablo Ferro Films.

After midnight, in January 1970, Pablo and a friend, who just returned from the Vietnam War, waited on some other guests. Pablo answered a knock on the door to see a gun pointed at him. The assailant shot him in the neck and ran off. It aeems the gunman mistook him for another tenant in the building. His friend had enough battlefield medical experience to keep Pablo alive until police arrived. It was touch-and-go for a few days, but Pablo survived.

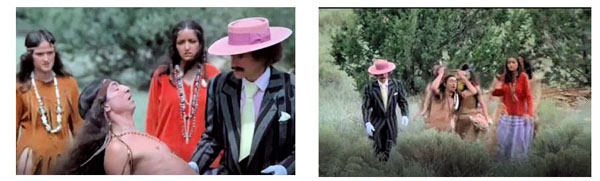

In 1971 Pablo created titles and a trailer for Stanley Kubrick’s infamous A CLOCKWORK ORANGE. That trailer is considered to be a classic. Titles for his friend Hal Ashby’s directorial debut HAROLD AND MAUDE followed the next year. Pablo did bouncy titles for Robert Downey’s GREASER’S PALACE, and played ‘the Indian’. Pablo’s character suffers from a spinal ailment that is cured by the touch of a Jesus figure. The fully restored Indian handsprings to his feet, perhaps a metaphor for Pablo’s personal resurrection.

Reborn, Pablo had evolved beyond being an animator, beyond directing television commercials. Phil Kimmelman & Associates still called him in to consult, but Pablo exhibited little patience at those meetings. Clients got annoyed as Pablo refused to entertain any approach to an ad aside from his own. Phil loved the guy, but stopped calling him in. At the same time, movie studios kept Pablo busy with trailers for SCENES FROM A MARRIAGE, JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR, and O’ LUCKY MAN in 1973. Phil still relied on Pablo for sage advice, and once told me he saw Pablo as a philosopher.

Pablo hung out with Phil on the east coast and Hal Ashby on the west coast. Ferro’s titles embellished Ashby’s 1976 movie BOUND FOR GLORY. Pablo Ferro was a fixture along that strip known as Popeye Alley. Arnie Levin also inhabited “Forty-five” West 45th Street as a partner in a studio called Phos-Cine. Arnie’s wife Pam did inking across the street at 18 West 45th for Lester Osterman Productions on the feature-length animation RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY: A MUSICAL ADVENTURE.

Pablo hung out with Phil on the east coast and Hal Ashby on the west coast. Ferro’s titles embellished Ashby’s 1976 movie BOUND FOR GLORY. Pablo Ferro was a fixture along that strip known as Popeye Alley. Arnie Levin also inhabited “Forty-five” West 45th Street as a partner in a studio called Phos-Cine. Arnie’s wife Pam did inking across the street at 18 West 45th for Lester Osterman Productions on the feature-length animation RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY: A MUSICAL ADVENTURE.

Howard Beckerman ran a studio at 18 West 45th, occasionally dining with Pablo. It amused Howard that even if a restaurant was in walking distance, Pablo insisted they take a cab . . . because “You’re in New York, you take a cab!”

Minor league pitcher turned Broadway producer Lester Osterman pulled out all the stops with RAGGEDY ANN & ANDY: A MUSICAL ADVENTURE. Crews labored over it on both coasts. Richard Williams, perhaps the most dedicated animator who ever lived, directed, dashing about with boundless energy. Legends like Art Babbitt, Grim Natwick, Tissa David, Emery Hawkins, Willis Pyle, and Gerry Chiniquy were supported by Fine NYC regulars such as: George Bakes, Jerry Dvorak, Jim Logan. Jack Schnerk, and Michael Sporn. Ida Greenberg was in charge of planning and ink & paint. Camille Marinelli and Nancy Massie were animation checkers.

It feels like a last hurrah for the greatness that Popeye Alley once exhibited. It would be Pablo Ferro’s last big connection to the animation scene when he was chosen to create the titles for this movie.

During 1978 Pablo Ferro Films closed. Hal Ashby owned a house near Los Angeles in Calabasas that he’d converted into a post production facility, with a one room living quarters. Ashby’s crew called the place “Camp Crater Oakee”. Hal Ashby also co-owned a Malibu apartment building with producer Lou Adler. Pablo was given access to both. Ferro did titles for Ashby’s critically acclaimed film BEING THERE. Ashby directed the Rolling Stones concert film LET’S SPEND THE NIGHT TOGETHER in 1981 with Pablo as Creative Consultant.

His son Allen joined him in California. Pablo taught Allen how to ink cels, shoot exposure tests, and work in the darkroom. Allen learned “creative” editing, and made his way into the motion picture editors’ guild. Allen Ferro assisted his father on title jobs, eventually becoming Pablo’s manager and creative producer. Allen soon found himself editing film while enmeshed in the art world, regularly smoking weed and playing poker in Malibu with Wally Wood.

Pablo needed the help. Chronic pain caused by his neck wound brought about dependency for pain killers. At Michael Jackson’s request, he supervised editing for the BEAT IT video in 1983. Jonathan Demme directed the Talking Heads concert movie STOP MAKING SENSE in 1984 with titles designed by Pablo Ferro. The drug-fueled music scene was not the best place for someone with an addiction. Too many pills make a person less rational. Pablo often chastised his crew with Dante’s old lecture about being there to work, not chase women. At the same time Pablo was seducing women on his crew.

Pablo’s daughter Joy moved to L.A., so he hired her as Assistant Director on the movie RAGE that. RAGE is listed as being made for television and seems to have never made it to VHS or DVD. By then Susan was ready to marry someone new, but neither she nor Pablo had ever filed for divorce. They eventually did. He bought a house on Dunman Avenue in Woodland Hills, overlooking the West Valley.

Pablo’s daughter Joy moved to L.A., so he hired her as Assistant Director on the movie RAGE that. RAGE is listed as being made for television and seems to have never made it to VHS or DVD. By then Susan was ready to marry someone new, but neither she nor Pablo had ever filed for divorce. They eventually did. He bought a house on Dunman Avenue in Woodland Hills, overlooking the West Valley.

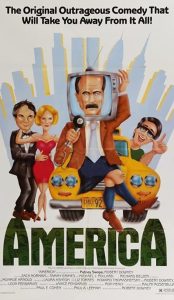

Robert Downey Sr. cast Pablo in the 1986 movie AMERICA, which is unfortunately hard to find. Tim Burton reached out for Pablo to envision the BEETLEJUICEtitles. Oh, to be a fly on the wall at those meetings. Sam Raimi came along next, tapping Pablo’s skills for DARKMAN. Universal Studios hired Pablo to help finish the film, Pablo and Allen experimented with the Kiniscope process of transferring video to film for the DARKMAN rage sequences.

Having firmly established himself in Tinsel Town by 1992, Ferro directed the theatrical feature film ME, MYSELF AND I, starring his pal George Segal and JoBeth Williams. Joy would be his production assistant, and Allen would be supervising editor on the film. As might be expected, Pablo stepped beyond societal norms. Without aggressive marketing the movie fizzled (watch it on tubi). With Allen at his side, Pablo did titles for THE ADDAMS FAMILY movie, then Jonathan Demme’s PHILADELPHIA in 1993. Allen did much of the actual work by that point, always saying that his father was one of the world’s great visionary Art Directors.

There were a number of New Yorkers resettled in Hollywood. Pablo’s close friend, actor Reni Santoni, had a good gig playing Poppie on SEINFELD. Robert Downey’s unusually straight=laced HUGO POOL (1997) concerns a Hollywood pool cleaner, played by Alyssa Milano, and a day in her life. At one house salsa music plays while Pablo Ferro dances with the ladies. The plot wraps around a strained father-daughter relationship.

Pablo’s relationship with his own daughter Joy was better.

Pablo’s relationship with his own daughter Joy was better.

Still complicated. Allen took a job with Paramount Studios marketing division, still working as Pablo’s creative partner on titles and trailers. Joy was their father’s agent and manager, keeping track of myriad publicity details. In 1997 Joy signes Pablo on with four motion pictures that won Oscars: GOOD WILL HUNTING; MEN IN BLACK; L.A. CONFIDENTIAL; and AS GOOD AS IT GETS, following that impressive list up in 1998 with HOPE FLOATS; DR. DOOLITTLE; BELOVED; and the HBO movie WINCHELL, as the Directors Guild of America honored Pablo Ferro with a Special Achievement Award. Michael Cimino presented the award, having once worked for Ferro and Mogubgub.

Pablo received the Daimler Chrysler Design Award for Film Design in 1999, and was inducted into the Art Directors Hall of Fame the next year. In his later guise as an elder statesman for the arts, Pablo took to sporting a long red scarf, materializing at conventions, galas, and award ceremonies (often thrown in his honor). Pablo mingled among his fellow designers, animators, actors, directors, editors . . . advising an upcoming generation. Art students in Texas revered him. He lectured at venues such as Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts, and as far away as Australia, gliding through into a new century as an established icon. MY BIG FAT GREEK WEDDING, the runaway hit movie of 2002, bore his title work.

Pablo had become prickly. Impatient. Infuriating. He once walked, unannounced, into a board meeting at Universal Studios, right past the president and other executives without a word, to retrieve a tape he didn’t feel was ready. Perhaps it was PTSD, perjaps Depression, combined with unrelenting pain caused by the gunshot. Allen and Joy looked after him.

Pablo had become prickly. Impatient. Infuriating. He once walked, unannounced, into a board meeting at Universal Studios, right past the president and other executives without a word, to retrieve a tape he didn’t feel was ready. Perhaps it was PTSD, perjaps Depression, combined with unrelenting pain caused by the gunshot. Allen and Joy looked after him.

His alma mater Industrial Arts had morphed into the School of Art and Design. They granted Pablo Ferro an honorary degree in 2009. He did book illustrations for THE TWO SISTERS CAFE by Elena Yates Eulo and Samantha Harper Macy in 2010. The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston presented Pablo an award in 2011. The man was the subject of a 2012 documentary film titled PABLO. He was then living in a garage studio at the home of his son Allen, working out of the Title House in Hollywood.

He became ill in 2015 and Joy brought her father to Sedona, Arizona, where he continued to work. Pablo reconnected with Dante Barbetta by phone, and kept in touch with Phil Kimmelman. Those early days, animating in Brooklyn, must have seemed a dozen lifetimes away. In 20I8 Pablo Ferro left this world.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

BOB COAR made his way in this world as a muralist and sign painter, illustrating on just about every surface imaginable. A life-long fan of animation, he is currently searching for digital, or actual, copies of Top Cel.

You glossed over the sad fate of Tempo Productions, which didn’t “peter out” but was a deliberate target of Cold War politics and paranoia. In December 1953, when Pablo Ferro had been working at Tempo for no more than six months, an anti-communist newsletter called The New Counterattack ran an article titled “Big Business Firms Ignore Important Facts About Tempo Productions”. It accused founder Dave Hilberman and sales director William Pomerance of being communists and also listed 11 major ad agencies and 22 corporate clients that they claimed were “subsidizing” Tempo. In 1954 Walter Winchell got his hands on the New Counterattack article and repeated the charges in his own newspaper column. By the end of the very next day, all of Tempo’s clients had severed their relationships with the studio. It was as quick and as simple as that. Dozens of people lost their jobs on the basis of accusations that never would have held up in court. Hilberman had to relocate to England because no one in America would hire him; Pomerance never worked in animation again. Tempo didn’t “transition” into Academy Productions; Academy was a Los Angeles-based company that wanted a studio in New York, and they simply moved into the space that Tempo had vacated. They did hire some former Tempo staffers like Pablo Ferro, but it was a different company with different management.

Given that history, it’s ironic that Ferro made the trailer and titles for HBO’s “Winchell” movie.

The “piano factory” in Hell’s Kitchen didn’t manufacture pianos as such, but only the internal action mechanisms which they in turn sold to low-budget piano manufacturers (high-end piano companies like Steinway and Baldwin always made their action mechanisms in-house). It must have been a hellish sweatshop, but the company folded during the Depression, before Ferro’s family moved into the neighbourhood. The building stood vacant for decades until it was converted into loft apartments in the 1980s. To this day the building is known as the Piano Factory.

I hope you’ll have more to say about Fred Mogubgub in future posts; he sounds like an interesting character. I’m sure I’ve seen his name in MAD magazine, but I don’t know whether he was a contributor or just on friendly terms with some of “the usual gang of idiots.”

Another eye-opening column; thanks Bob.

Wotta career. Wotta network of creatives. Without knowing who Pablo Ferro was, I remember all those 60s movie trailers and credits. Even as a kid, I was mesmerized by the Burlington weave logo on TV.

That’s why I come here, to learn stuff.

Ferro was one of the first professional filmmakers I met. He was lecturing at my school and I was lucky enough to get some time to chat. I was most impressed that he created the titles for Dr. Strangelove, but for some reason, he was most proud of his work on timing the titles to West Side Story for Saul Bass. He also mentioned that he created the titles (uncredited) for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and I had a burning question to ask: did he know how they created the long pullback for the final shot. I asked the right person because he created that. And if you don’t know or remember, Butch and Sundance are outnumbered and they run out, guns blazing, the frame freezes, fades to B&W, and then pulls way back to show they are impossibly surrounded. I knew you couldn’t zoom in on a film frame without getting unusable grain. He explained they made a photograph of the last frame and they also used a high-resolution still camera for a wide shot. He cut out the figures from the frozen frame, pasted it on the wide shot then matched it on the animation stand and pulled back from the composite. The background shifts a bit because it’s from two different cameras, but your eyes are on the two main actors who match perfectly. I probably learned more from that meeting than any of my art classes.

Wow. I never imagined that the film’s complex final shot was created in that way. A great story! Thanks.

Outstanding column Bob-Pablo seems like a bit of a Renaissance man for sure.

Approximately, how many movie titles did Ferro make?

Fantastic work, Bob! As a fellow Cuban from NYC this was a special treat. I’m ashamed at how little I knew about the man. A mindblowing path to greatness.

Thanks, Bob for this excellent article on our beloved Pablo and especially for the many details tracing back along his earlier life & career. We were in a romantic relationship as well as a working relationship in the early to mid 80s. I was deeply fortunate to have met, known and loved Pablo and to have been loved by him. Our time together was a deep learning for me while working for him and with him on many projects. My mind was altered as a pre-teen watching his Burlington ad and others on TV. They grabbed me! I marveled seeing him in Greasers Palace in 1974 and little did I know we would spend much time together over several years and that I would be immersed in the world of Pablo Ferro! We were in NYC during June 1981 working on Bob Downeys film Moonbeam, and Pablo took me to the animation house he once worked at introducing me to several giants of that world, all kind and gentle men. I’ll never forget the man who created Baby Huey. He looked just like that gentle giant!

I have some clarification of a few details if you’re interested, and if not, that’s okay. There’s nothing on Pablo and his life and work like this anywhere online. Gratitude to you for doing all the work and honoring this unique genius as he deserves to be seen.

Pablo Ferro Forever!

🩷Versatility & Love 🩷

Would love to talk. Perhaps Jerry can provide you my email.