While at Warner Brothers in 1936, Bob Clampett animated and contributed gags but he really wanted to direct and so he tried to develop some projects of his own.

“I had been fascinated with the (Edgar Rice) Burroughs books since I was a youngster, especially the Mars books,” Clampett told me when I interviewed him in 1978. “Realizing the potential of a fantasy series of cartoons based around Burroughs’ characters, I went out to Tarzana (in the San Gabriel Valley) to see Burroughs himself and tried to convince him that I could film and sell a series of cartoons based on his John Carter of Mars stories.”

Clampett was surprised to find Burroughs so receptive to the idea of animation. Burroughs wanted to see his characters receive further exposure, perhaps because his other creations were currently being overshadowed by the enormous success of Tarzan. Burroughs also realized that the medium of animation would allow for special effects and an outer space setting that might be cost prohibitive or poorly done if translated to existing live action film techniques.

Although Burroughs had some experience with movies (even organizing his own film company at the time), he was less familiar with the world of animation. As Clampett remembered, “As far as animation was concerned, he was completely in the dark. Edgar was smart enough to understand that one couldn’t just literally translate his Mars books page by page into animation; it just would not be cinematic. So, he gave me a great deal of freedom to dream up and be inspired by his writing and develop a cartoon story on my own.”

At the same time, Burroughs’ son, John Coleman Burroughs had recently graduated college. He became interested in this revolutionary animated series. John set about sculpting several articulated models so that Clampett could more easily see how the animals and other important objects might look and move. Several of those sculptures still exist today.

At the same time, Burroughs’ son, John Coleman Burroughs had recently graduated college. He became interested in this revolutionary animated series. John set about sculpting several articulated models so that Clampett could more easily see how the animals and other important objects might look and move. Several of those sculptures still exist today.

John also did a series of sketches with detailed notes along with some colored drawings that with the sculptured models were invaluable in trying to achieve a sense of reality in an unreal setting.

Clampett immediately got to work to put together a test reel of footage. He had to have a major conflict that got resolved, introduce the main characters, and establish the strange world of Mars. The basic plotline that Clampett settled on concerned an exotic race of Martians who lived in the mouth of a volcano.

Periodically, they would venture out from their hidden lair in rocket ships to attack and plunder the cities of Mars. Of course, it was up to hero John Carter to stop them.

While it was Clampett’s plan that the series would be composed of nine-minute long cartoons, each of which would feature a complete story, he decided that just a few minutes of test footage would be ample to convince any distributor of the viability of the series.

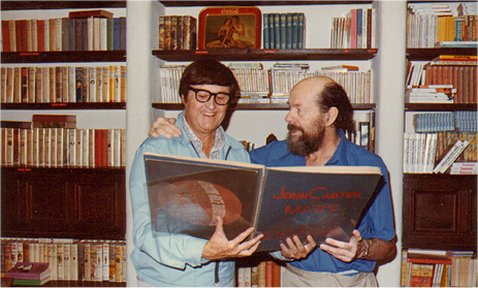

Bob Clampett and John Coleman Burroughs in the 1970s

Edgar Rice Burroughs himself had already contacted MGM about buying the animated series. MGM was anxious to keep Burroughs happy since they were enjoying success with their Johnny Weissmuller film version of Tarzan and they were generally dissatisfied with their animated short subjects at the time. So, Clampett was under pressure not only to make test footage that would satisfy Burroughs but also the more pragmatic accountants at MGM.

“I wanted to do something quite imaginative, with tongue-in-cheek humor throughout. Chuck (Jones) helped me animate and Bobe (Robert Cannon) in-betweened. In fact, I filmed Bobe bare-chested in live-action as the hero; he was very heroically built, all shoulders and no hips. I filmed him in Griffith Park, and we rotoscoped part of it,” recalled Clampett.

“I wanted to do something quite imaginative, with tongue-in-cheek humor throughout. Chuck (Jones) helped me animate and Bobe (Robert Cannon) in-betweened. In fact, I filmed Bobe bare-chested in live-action as the hero; he was very heroically built, all shoulders and no hips. I filmed him in Griffith Park, and we rotoscoped part of it,” recalled Clampett.

Because Clampett and the others were still working full-time at Warners, the John Carter work had to be squeezed in at night, on weekends and whenever a spare moment managed to pop up. Even John Coleman Burroughs and his fiancée Jane would sometimes help out by painting some of the cels for the cartoon themselves.

“We would oil paint the side shadowing frame-by-frame in an attempt to get away from the typical outlining that took place in normal animated films. In the running sequence, for example, there is a subtle blending of figure and line which eliminated the harsh outline. It is more like a human being in tone. We were working in untested territory at that time. There was no animated film to look at to see how it was done,” stated Clampett.

In 1936, the test footage was completed. It featured John Carter running and leaping around the Martian surface, a Thark riding a thoat in full color, Carter involved in a swordfight and other vivid sequences which were quite unlike anything else being done in animation at the time. There was an opening title sequence of the planet Mars hurtling toward the screen with lettering proclaiming John Carter in the “Warlord of Mars” and title cards announcing future episodes.

It was planned that these scenes would be incorporated into the first film if the series sold. Burroughs loved the final work and more importantly, so did MGM. Clampett gave notice to Warners that he was leaving and he started production work on the first episode.

The local MGM sales representatives who were primarily from the Mid-West and the South expressed their concerns to MGM that the project would be a “tough sale”. They felt audiences would not be able to understand nor accept the concept of an Earth man having adventures on Mars. It all just seemed too strange. The first Flash Gordon movie serial had not yet been released. They pushed for a Burroughs cartoon series featuring Tarzan who was already well-known and well-loved by the public. Clampett was heartbroken.

The local MGM sales representatives who were primarily from the Mid-West and the South expressed their concerns to MGM that the project would be a “tough sale”. They felt audiences would not be able to understand nor accept the concept of an Earth man having adventures on Mars. It all just seemed too strange. The first Flash Gordon movie serial had not yet been released. They pushed for a Burroughs cartoon series featuring Tarzan who was already well-known and well-loved by the public. Clampett was heartbroken.

The MGM cartoon concept would be funny animals doing silly things and then at the end of the cartoon, Tarzan would briefly appear and save these foolish animals from being caught in quicksand or facing a vicious predator.

Clampett stored away the storyboard, notes, sketches, actual cels and completed footage of the John Carter project and for the most part, forgot about the aborted series until he started lecturing at events and colleges.

Forty years later, Clampett told audiences, while working on John Carter, he developed the idea of a city protected by a gigantic glass bubble. There was huge helicopter blade on top of this glass dome so that in times of trouble when the city was threatened by invaders, the city could just lift up into the air, fly to a place of safety and descend.

“The drawings I made look exactly like a beanie cap, so I guess you could say that perhaps I have Edgar Rice Burroughs to thank for providing the inspiration for the beany-cap-copter in Beany and Cecil,” laughed Clampett.

The Beany and Cecil: Special Edition DVD features as a supplement most of the existing animated material with some of this footage actually narrated by Clampett himself in commentary that was obviously borrowed from one of his university screenings of the material.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Such a pity those two minutes were all that were produced. That would have been an amazing series, and probably pretty popular.

As much fun as it would be to see a series of John Carter of Mars series by Bob Clampett, it would have been a terrible loss to the Warner Bros cartoons. Who would have done all those black and white Porky Pig cartoons? …Hardaway and Dalton? Would there have been a Bugs Bunny series? Would Daffy have continued? Would Chuck Jones have left the studio with Bob Clampett? Would Bob McKimson have ended up with Chuck Jones’ future unit?

Keep in mind that Avery would still be there and he was the one that helped created Bugs Bunny and not Clampett.

Even with Avery still there, if Jones left to work on John Carter, you wouldn’t have had “Elmer’s Pet Rabbit,” or “Daffy Duck and The Dinosaur.” With those cartoons missing and the wackiness of Bob Clampett’s Porky cartoons missing, the studio’s cartoons might have gone in a different direction. “A Wild Hare” might not have gone into production, and the same with the Freleng’s Daffy Duck redesign in “You Ought to be in Pictures.” I believe Clampett was essential to the studio’s development. He also was needed to take over the Avery unit.

A few years back, a cell from this project was sold on Heritage Auctions. The auction description indicated they were unaware of the historical importance of the cell, and the final price was relatively low, alas, higher than my budget at the time. It can still be seen on their archives:

https://historical.ha.com/itm/books/-animation-art-john-coleman-burroughs-artist-original-animation-cel-for-unrealized-john-carter-of-marsandlt-/a/6169-96021.s?ic4=GalleryView-ShortDescription-071515

Damn, whoever won it got off lucky there.

As a kid, I remember seeing something about this on To Tell The Truth; maybe someone who rediscovered it? That’s all I remember. Anyone know? Maybe 1969-70?

It’s interesting to speculate how different American animation would be if a project like this was not only produced but was successful. Except for the Fleischer Superman series and a few WWII propaganda shorts like Education for Death, there are almost no serious action-adventure cartoons during the classic era; a hit John Carter of Mars animated serial could have changed all that.

It’s only a shame we have the MGM sales reps. to blame for not foreseeing this further when they felt a Tarzan-related cartoon was a better priority.

Although not an animator, I met Bob while I was living in San Francisco in 1975 studying piano and composition at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. We hung out together at the great “Owl and the Monkey Cafe” at 9th Avenue and Irving Street adjacent to UCSF Medical School. Bob introduced me to some of the earliest examples of computer animation. Thank you for publishing this outstanding tribute to Bob. The memories make me feel like I’m 21 again.