In the 1950s, movie theaters were changing, as they are in today’s world, where streaming options have impacted the current moviegoing experience. But, back in the 1950s, it was the then, still-new, technology of television that was keeping audiences at home.

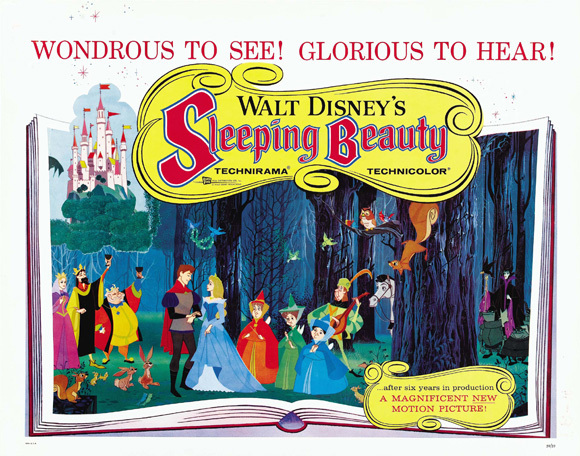

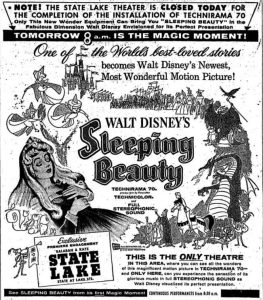

To bring people back to theaters, one of the tactics was widescreen, epic films, giving audiences experiences like Technirama, VistaVision, Cinerama, and CinemaScope that couldn’t be duplicated on TV screens, and films like The Ten Commandments and Giant were treated less like movies and more like a concert or event.

At the time, Walt Disney utilized Cinemascope for his animated feature, Lady and the Tramp, in 1955. With his next feature, Sleeping Beauty, larger in scope and more epic, it emerged as an “event film” and was made using the Technirama process.

At the time, Walt Disney utilized Cinemascope for his animated feature, Lady and the Tramp, in 1955. With his next feature, Sleeping Beauty, larger in scope and more epic, it emerged as an “event film” and was made using the Technirama process.

“This was Walt wanting to be a part of what the movie market was at the time,” said Disney historian Jim Fanning, who has authored a number of books, including Drawing 100 Years of Disney Wonder. “Competing with television, there was widescreen, and there were also ‘roadshow attractions.’ These were specially made movies, where you would buy tickets in advance, as you would for a play. It was a whole experience. With Sleeping Beauty, they stepped away from the reserved seat policy, but it only played in special theaters, and the cost of the ticket was higher. The biggest movie that year [1959] was Ben-Hur, the ‘roadshow attraction’ to end all ‘roadshow attractions.’ So, this was also Disney wanting to be in that field with something special to compete with these other grand films.”

Celebrating its 65th anniversary this year, Sleeping Beauty was first considered as a project at Disney in 1950, and during the nine years before it reached the screen, it was in production during a unique time at the Disney studio, as author Bob Thomas remembered in his book Disney’s Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Beauty and the Beast:

“The film was developing during the mid-fifties when Walt was enmeshed in Disneyland, the Mickey Mouse Club, Zorro, and Disneyland television shows. The Sleeping Beauty story men and animators often waited weeks before Disney could meet with them.”

However, from this came a unique Disney animated feature based on the 1697 fairy tale by Charles Perrault, as it told the story of Princess Aurora (voiced by Mary Costa), who is cursed by the evil Maleficent (Eleanor Audley, who had also voiced Lady Tremaine in Disney’s Cinderella and would also voice Madame Leota in Disney’s Haunted Mansion attraction).

Scorned at not being invited to the Princess’ christening, she curses the child by stating that as the sun sets on Aurora’s sixteenth birthday, she will prick her finger on a spinning wheel and die.

Scorned at not being invited to the Princess’ christening, she curses the child by stating that as the sun sets on Aurora’s sixteenth birthday, she will prick her finger on a spinning wheel and die.

Princess Aurora is saved by the three good fairies, Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather (Verna Felton, Barbara Jo Allen, and Barbara Luddy, respectively), who are unable to remove Maleficent’s curse but change it so that the Princess will not die but instead fall into a deep sleep upon pricking her finger, to be awakened by true love’s kiss.

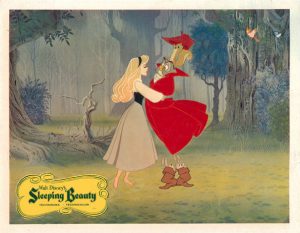

The three fairies also take the princess deep into the woods, hiding with her in a cottage and renaming her Briar Rose. While here, on her sixteenth birthday, when the fairies are to return the princess to the King and Queen, Briar Rose meets Prince Phillip (Bill Shirley) while walking in the woods, and the two fall in love.

Maleficent, who has been searching for the Princess all this time, discovers her whereabouts and vows to enact her revenge.

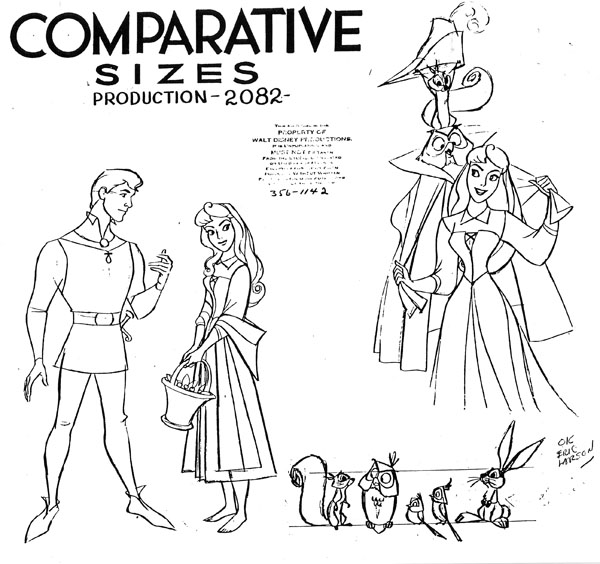

Even though he may have been distant to the artists while Sleeping Beauty was in production, Walt did have a specific vision that he relayed to them. “He said, ‘Let’s make the ultimate animated feature,” said Fanning. “That was his goal – the greatest in artistry, the greatest in the animation of the human form, the greatest in music, and the greatest in storytelling. He really set out to make this a special and unique work of art. He wanted animation to be an art form. He told his artists, ‘Every frame of this film has to be a work of art.’”

This was realized through the masterful artistry of Eyvind Earle, a background artist at the studio who served as the supervising color stylist/inspirational sketch artist for Sleeping Beauty. In his book Before the Animation Begins: The Art and Lives of Disney’s Inspirational Sketch Artists, author John Canemaker wrote, “For the film’s visual style, Earle created an opulent medieval tapestry based on the paintings of Durer, Van Eyck, Breughel, and fifteenth-century French illuminated manuscripts, particularly the Tres Riches Heuvres de Jean, Duc de Berri.”

Earle’s style became the Sleeping Beauty style, informing all corners of the film and giving it a unique look that differentiated it from any other Disney animated film. The style also influenced character design, including that of the film’s villain, Maleficent, who was brought to the screen by Disney Legend and member of the Nine Old Men, animator Marc Davis.

In a 1998 interview, Davis (who also supervised the animation of Princess Aurora for the film) noted that the character was a challenge from an animator’s perspective: “…the hardest thing with Maleficent was how to bring her to life. She did stand up and make speeches, but that’s when I introduced the Raven. This way, she could work to the Raven. She had a wonderful voice. Eleanor Audley, wonderful lady.”

With Maleficent, Davis crafted one of film’s most memorable and chilling screen villains.

As part of the film’s climax, Maleficent transforms into a fire-breathing dragon that Prince Phillip must battle. The sequence, directed by the legendary Wolfgang Reitherman, remains one of animation’s most indelible and dynamic action sequences.

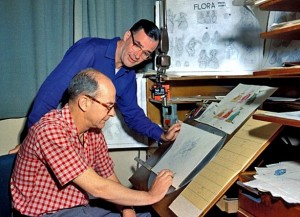

Ollie Johnston, seated, and Frank Thomas in May 1957, work on the Three Good Fairies from Sleeping Beauty.

Wrapping around the story is a lush musical score by George Bruns, who adapted Pyotr Tchaikovsky’s 1890 ballet (for more of the music of Sleeping Beauty, check out Greg Ehrbar’s 2014 article).

Released on January 29th, 1959, Sleeping Beauty received mixed reviews from critics and was a box-office disappointment. At a cost of $6 million, it was the most expensive animated film of its time and didn’t re-coup those costs during its initial run.

Of course, sixty five years later, like most “ahead of its time” films, Sleeping Beauty has earned its much-deserved appreciation as a pinnacle of animation artistry and a beloved moment in Disney history. It has inspired subsequent generations of audiences and artists (the look of Disney’s 1995 feature Pocahontas is just one of many animated films that drew inspiration from Sleeping Beauty).

“It’s very special,” said Fanning of the film, adding, “and it gladdens my heart that through the years, Sleeping Beauty has been more and more recognized as the beautiful work of art that it is.”

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Michael Lyons is a freelance writer, specializing in film, television, and pop culture. He is the author of the book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance, which chronicles the amazing growth at the Disney animation studio in the 1990s. In addition to Animation Scoop and Cartoon Research, he has contributed to Remind Magazine, Cinefantastique, Animation World Network and Disney Magazine. He also writes a blog, Screen Saver: A Retro Review of TV Shows and Movies of Yesteryear and his interviews with a number of animation legends have been featured in several volumes of the books, Walt’s People. You can visit Michael’s web site Words From Lyons at:

Walt Disney got his wish: every frame of “Sleeping Beauty” is a work of art.

In many ways the film represents the artistic culmination of the studio’s first three decades. Animation, design, backgrounds, and effects all equaled or surpassed anything Disney had heretofore achieved. Even the ink and pain work is extraordinary. After “Sleeping Beauty”, the art of inking would be supplanted by xerography, and the production of Disney features would largely be a matter of cutting corners.

Flora, Fauna, and Merriweather are wonderfully engaging characters; they remind me of many women I’ve known. Of course they get a lot more screen time than Princess Aurora, but what of it? “Sleeping Beauty” is Aurora’s story, no question about it, but the three good fairies are its heroines.

It distresses me that in recent decades critics tend to place “Sleeping Beauty” in the middle rank of Disney features, or even a bit below. As far as I’m concerned, it stands on a par with Disney’s greatest masterpieces. Every time I watch it — and I just did, again — it never fails to bring the tears to me eyes.

While I appreciated and enjoyed this film as a child, it was only after I reached adulthood and observed the artistry that went into it that it became a cherished favorite. This is one film in which Disney was reaching for high art, much of which is achieved, but partly at the cost of character development which had been a strong suit of previous Disney animated features. In the 30’s Disney was the darling of the critics and of adult audiences, which provided the opportunity for “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” to charm and dazzle and to be taken seriously. By the 1950’s Disney had an established reputation as a purveyor of kiddie fare and family amusements, which I believe undercut the company’s ability to reach its targeted audience for this film. Cartoons in general had, through exposure on television and the gradual establishment of Saturday morning as a time for kids’ viewing, become less associated with adults, who from this point in history had begun to shy away from anything animated as being purely for kids.

If this film had been released in the climate of the 1930s it might have fared better, because there are so many touches that adults are better able to appreciate than kids. Walt Disney had a great love of classical music and of art for art’s sake, and this film is exactly that, a work of art. However, as far as drama and character are concerned, this falls below par in some respects–although none can argue that the dragon sequence is anything less than stunning.

An attempt is made to flesh out Aurora and Prince Philip and make them relatable characters, but their relatively limited screen time does not allow for the audience to bond with them the way they had been able to bond with Snow White or Cinderella. The three good fairies are on screen much more, but they are treated more as comic foils than as audience identification points. They are not our “friends” in the way that the Seven Dwarfs were, or Jimmy Cricket, or Cinderella’s mice. And the structure of the plot contains a well-developed Act One which essentially segues into a stirring and dramatic Act Three, but there is no Act Two to speak of to bridge the two main parts of the movie. (I would argue that the entire sequence from when Aurora is first introduced as a young woman is all part of the story’s big finale.) If there is an Act Two, it consists primarily of the film’s centerpiece song, “Once Upon a Dream” which sequence in itself is near perfection.

I absolutely love this film. When I want to see animation that I can savor and music that soars to lofty heights, artwork that dazzles the senses, there is no better film than “Sleeping Beauty”. But when I crave characters I can relate to, there is more of that to be found in “Lady and the Tramp,” “Peter Pan,” “Snow White,” “Cinderella,” “Bambi,” “Dumbo,” “Pinocchio,” and many other of the Disney animated classics.

It’s funny how we’re in an era where both TV and movies are in flux because of another technology, and Disney is somewhat in trouble because the movie they just made is contentious and didn’t make so much money.

Reminds me: I forget who on Twitter, but they balked at the lack of marketing for Strange World by pointing out that Disney got people excited for Sleeping Beauty by building that castle in Disneyland. Now, Strange World was woefully undermarketed (Chapek thought little of animation, and IIRC took marketing control for films away from WDAS), but they completely failed to point out that Sleeping Beauty failed at the box office. It took decades for its reputation to recover! (at least with Disney artists; I seem to recall it was still a tough topic at the studio by the 80s)

Sometimes animation discussion is too ingrained in the “immediate now,” I suppose. That’s a lesson I’ve kept in mind after learning Sleeping Beauty’s reverance wasn’t so immediate.

First saw this at a drive-in on a double-bill with, appropriately enough, The Black Hole, as that was what the animation studio resembled after the costly failure of the original release. Didn’t see it again until decades later when I purchased the Blu-ray, and promptly did a Tex Avery eyeball take upon viewing the film’s opening moments. To say it was jaw-droppingly stunning doesn’t even come close. Ignore the thin characterizations and storyline, and just drink it all in.

One of the most heartbreaking of Disney’s animated features in terms of missed possibilities, the last gasp of the pre-Xerography classic style, and maybe still Hollywood’s most expensive 75-minute feature (allowing for inflation). It fails because there’s no center and little drama, just opulent surroundings and narrative sidesteps. Too much time is spent with the antics of the good fairies (“Pink!” “Blue!” “Pink!” “Blue!”), and the two kings squabbling is even less fun than the two kings squabbling in “Gulliver’s Travels.” The prince has a bit more personality and more to do than Snow White’s and Cinderella’s princes (who are prettier), but he looks different from scene to scene. As for Aurora, undoubtedly because she was so precisely designed and painstaking to draw, there’s not nearly enough footage of her for the audience to warm to her. She’s like the high school beauty whose reticence gets her a reputation for being stuck-up and aloof.

Maleficent’s speech to the imprisoned price is one of the best pieces of writing for animation, but the visual depiction lets it down: we should see the broken prince in rags crawling toward the open door and dying once he gets there. When hypnotized Aurora (in a wonderfully eerie sequence), approaches the spindle, Maleficent’s voice should be dulcet and enticing rather than stern and commanding (“Touch it, I say!”). And it needs to be established that Maleficent and the fairies can’t go into direct combat because they would destroy each other; still, the prince needs to vanquish the dragon himself rather than by Flora putting a spell on the sword. Better yet, Aurora’s animal friends could have been brought in to aid her rescue, as Snow White’s and Cinderella’s did.

If only the content had been as carefully worked out as the look, “Sleeping Beauty” would have been the fairest of them all. What do you suppose Merriweather’s wish for the baby princess would have been if Maleficent hadn’t barged in just then? I say the gift of chocolate.

Hey, that is not how you treat a film that’s a National Film Registry inductee. Besides, I consider Maleficent one of the coldest and darkest Disney Villains. I think she be in the top 10 and even 5 of the best Villans.

Anything with as nuts a making as that one is by-defult doomed, Apocalypse Now excepted.

Uh, what are you talking about?

Usually films with intensely troubled productions are doomed to be lukewarm. Apocalypse Now is the only film that went through heck that turned out a classic.

So has “Sleeping Beauty”. As I had said before, it has since been inducted to The Library of Congress’ National Film Registry in 2019.

Wonderful article, as usual, but the mention of a 1697 fairy story suggests a particular author and his name would be welcomed too. A little correction: the name is “Les Très Riches Heures du Jean, duc de Berry”. Just like Chuck Berry.

Thanks so much, Lucas, I appreciate it! You are so right, and Charles Perrault’s name should be in the article. It has been modified to include it, thanks to you. My apologies for leaving that out. The quote I used from John’s book had Berri spelled with an “I,”so I left it that way, as it was a quote. Interestingly, a Google search for Duke of Berry, who the manuscript was commissioned for, finds his name spelled both “Berry,” and “Berri.” Thank you again for the information and the comment!

I mainly remember Aurora as being the first character that introduced me to the concept of a “barefooter” character, that is to say a character that habitually goes barefoot wherever by choice. There’s been many characters like that since (TV Tropes has a whole article on it, entitled “Prefers Going Barefoot”) but Aurora was the first I saw that, and that particular character trait often finds it’s way in the stories I’ve attempted writing, where at least one character tends to go without shoes.

As noted, they re-released it on a double bill with the Black Hole, another visual wonder with story issues. True fact: In at least one day’s edition, the San Francisco Chronicle ran the ad among the porn theater promos. Some individual with a dirty mind saw the titles on a form and made an assumption?

Just started watching this one for the first time. Great-looking, yes, but kind of dull, but not as dull as Cinderella. I prefer the first five “Golden Age” films and the upcoming Reitherman Era to the Fifties.

I saw Sleeping Beauty fairly later in life than most of my generation did; as a young adult. I never got around to it until then. It struck me as a transitional film between the traditional Disney aesthetic of the 40s- mid 50s and the stylized, sketchy aesthetic of the 60s and 70s.

I do like the scene of the two kings’ interaction. It echoes the kings in Fleischer’s Gulliver’s Travels. (Similar in how the supporting characters had more personality than the leads.) One thing Ive noticed in the Fairy Tale adaptations done in Walt’s lifetime is that the princes screen time and personality went up exponentially in each film. In this one, he finally gets a name.

Despite my reservations, I can’t say no to a classic Disney feature. I am appreciating the use of color moreso.

As a child i was terrified by Maleficent and my aunt had to take me out of the cinema. So i was not able to see the film completely until 1978 and it was a dream for me. one of my preferred movie since then. Always very popular in Italy, it was reissued last time in 2000. And i was always in cinema to behold it. A beautiful 16mm print in Technicolor is in my collection

It’s worth mentioning that Mary Costa, who voiced Princess Aurora, is still with us at age 93. Another animation connection: she was married to Frank Tashlin from 1953 to 1966.

I first saw SLEEPING BEAUTY in 1971. Very good article!

This movie is as OLD as I am, and I’ve never really warmed up to it. Maybe the title and concept of it sounded either to “girly” or “babyish” to me when it was re-released? I don’t know. I’ve seen parts of it on Disney TV shows, etc. – but, as I said, it’s never been in my list of “Disney Classics.” I guess I need to give the film another look?

I didn’t think much of the pan-and-scan version when I watched it in the 1980s, but when I saw the widescreen laserdisc in the 1990s, I was mesmerized by it from start to finish. It makes me wonder what the movies after it could have been if it had made more money.

There is no denying ‘’Sleeping Beauty’’ is a magnificent film. I saw it countless times in theaters, beginning with the 1970 re-release. Although I wish Disney had stuck closer to the original story (she actually sleeps for 1OO years) I can understand why some of the alterations and revisions were made. Truthfully, in any classic fairy tale, the protagonist is almost always outshone by the villain(ess). ‘’Snow White’’ without the Wicked Queen?. ‘Cinderella ‘’ without the Wicked Stepmother and Stepsisters?. Too much character development for Hero or Heroine would weaken the story, I’m just glad that the intent of the original tale was retained, and it was not lost, as some critics stated, as a result of the visually elaborate way the film chose to dramatize it. The film has endured for 65 years, and will, no doubt, continue to do so. With what passes for ‘’family entertainment’’ today, that is truly a happy ending!

One thing that’s surprised me a little is that in the ’90s, those direct-to-home-video/Disney Afternoon TV show days, no one at Disney thought–or maybe they did and it just didn’t happen for whatever reason–to do a Briar Rose film or series, chronicling those 16 years when the Good Fairies are keeping Princess Aurora safely hidden in the forest that the film passes over so quickly. Every episode of a series could focus on Aurora/Briar Rose at a different age (it wouldn’t have to be sequential), making friends with the animals, the Good Fairies’ bumbling attempts to raise a mortal child without magic, Maleficent and her minions’ continued thwarted attempts to find her, and maybe even her meeting Prince Phillip as a boy (without, of course, them knowing who each other really is). The only real drawback is that the feature’s opulence could never be reproduced, and Maleficent in limited animation would be a shame. Still, if they ever decide to do it at some future date (probably live action), remember you heard it here first.

Another fantastic article, Michael! I’m currently reading your book, Drawn to Greatness: Disney’s Animation Renaissance and I recall you mentioned in the chapter about Pocahontas how much Sleeping Beauty had a major influence on that film regarding the art style. The Eyvind Earle influence was so prevalent in Sleeping Beauty, it truly speaks volumes for what a classic it merits being and how it suit the story. Given that the art style played such a pivotal role in shaping one of Disney’s Renaissance era films, it shows.