This is the third and final chapter of Jonathan Boschen’s “Rhapsody In Steel” articles. This final piece looks at the official remake, “Symphony In F”, which unfortunately is a film the author has mixed opinions on…

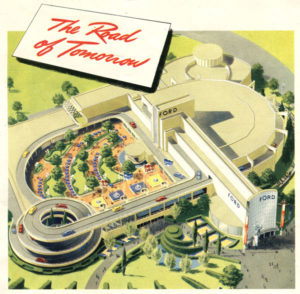

With the rave reception Rhapsody In Steel received while showing at the (1934) Chicago World’s Fair and afterwards, it was only a given that Ford and Audio Productions would eventually update the film in Technicolor. The official update was Symphony In F, which was shown at the second season of the 1939/1940 New York Worlds Fair (May 11, 1940 to October 27, 1940) in the Ford pavilion.

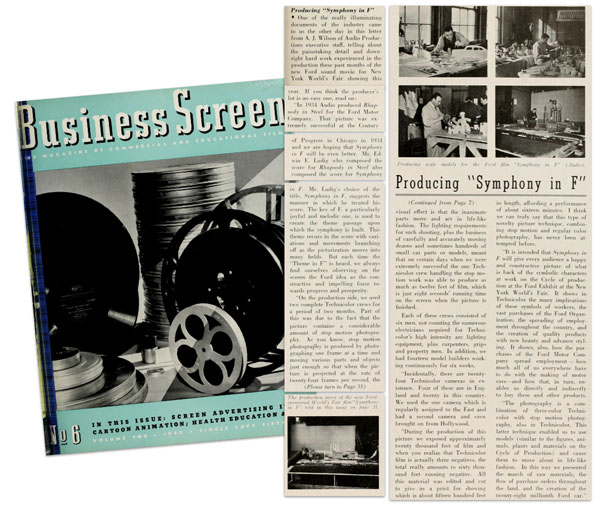

The director of this Technicolor ‘fantasy’ that featured stop motion and live action sequences, is officially unknown as no one is credited on screen or in trade articles (it was not Frank Goldman as he was working for Jam Handy), however it’s lavish music score was composed by Edwin E. Ludig, who was also responsible for the Rhapsody In Steel’s score. At the time of the film’s production and release in 1940, Business Screen Magazine gave it promising reviews and even credited it as the first film to feature [three-strip] Technicolor stop motion animation. (As history today shows, this is not accurate as George Pal was doing Technicolor stop motion films in Europe before 1940). It’s also a film which appears to have received mixed reception from the general public and also Ford executives. The author will admit that he has two different opinions on the production while as a stand alone film it is an entertaining piece of American ephemera, but as the remake of Rhapsody In Steel it’s not what it should have been.

The director of this Technicolor ‘fantasy’ that featured stop motion and live action sequences, is officially unknown as no one is credited on screen or in trade articles (it was not Frank Goldman as he was working for Jam Handy), however it’s lavish music score was composed by Edwin E. Ludig, who was also responsible for the Rhapsody In Steel’s score. At the time of the film’s production and release in 1940, Business Screen Magazine gave it promising reviews and even credited it as the first film to feature [three-strip] Technicolor stop motion animation. (As history today shows, this is not accurate as George Pal was doing Technicolor stop motion films in Europe before 1940). It’s also a film which appears to have received mixed reception from the general public and also Ford executives. The author will admit that he has two different opinions on the production while as a stand alone film it is an entertaining piece of American ephemera, but as the remake of Rhapsody In Steel it’s not what it should have been.

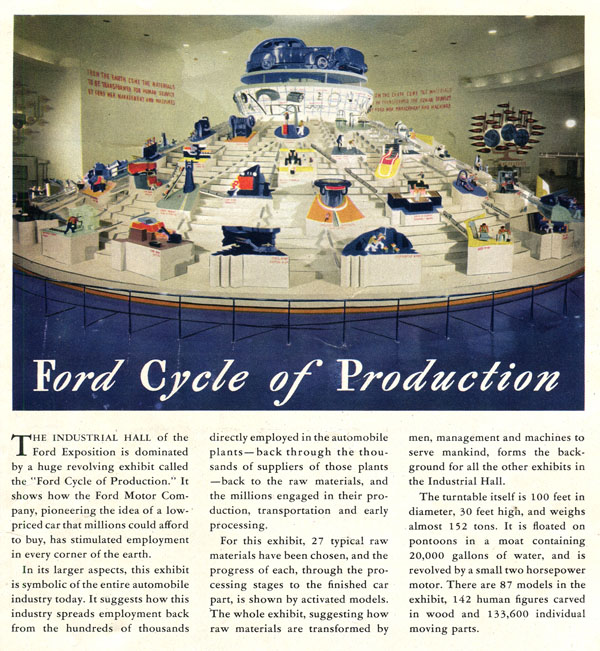

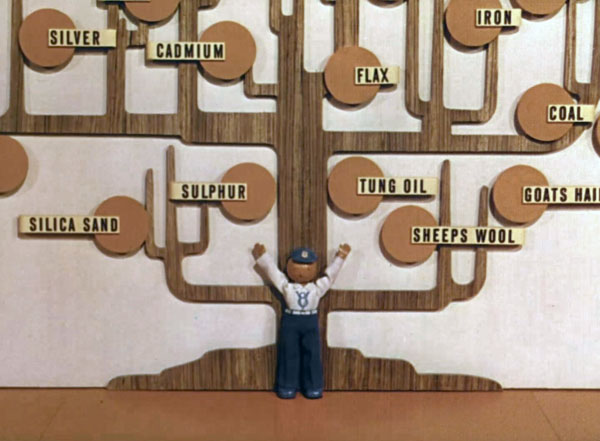

The objective of Symphony In F was to symphonically highlight and put into context one of the main attractions of the Ford pavilion, The Cycle of Production. This was a massive, rotating turntable exhibit which was one-hundred feet in diameter, and thirty feet high, that originally opened with the first (1939) season of the fair. (To rotate the 152 ton display, it was floated on pontoons in a moat holding 20,000 gallons of water, where it was rotated by a small horsepower motor). Twenty-seven different moving scenes were located on the exhibit demonstrating how raw materials were collected and transformed into Ford Cars, thus providing employment to hundreds of people. To depict the scenes the display put to use eighty-seven models, 142 mechanical puppets and 133,600 moving parts that were powered by the turntable’s rotation.

As Symphony In F highlight’s this display it plays out much differently than it’s 1934 predecessor, making it an entirely different production that can be divided into three parts. The film’s first third is a stop motion animation sequence that musically highlights the Cycle of Production model scenes, while the second third of the film is a live action sequence that symphonically showcases the Rouge River plant and how the various model scenes relate to it. The final third is another stop motion animation segment in which characters representing the Cycle of Production models hold a parade to celebrate the completion of Ford’s 28,000,000 car. No narration is featured in the production and instead relies only on Edwin E. Ludig’s music to relate the scenes.

Who directed and/or animated Symphony In F is a little bit of a mystery as a director’s credit is not included in the film’s credits nor in the trade articles highlighting the film. However from researching Audio Productions the author believes the director and stop motion animator may have been a man named Henry L. Roberts (sometimes credited as H.L. Roberts). Prior to Frank Goldman’s departure from Audio Productions to Jam Handy in 1935, Roberts frequently worked with him on mixed media films that featured stop motion animation. Roberts basically took Goldman’s reigns in 1935/36 and kept his filmmaking style alive at the studio, as can be seen with the 1935 film The Wonder World Of Chemistry (produced for E.I. Du Pont), the Let’s Go America series (produced for the National Industrial Council), and 1937’s Singing Wheels (A Wilding Pictures Production for the Automobile Manufacturers Association that was apparently subcontracted out to Audio Productions). It’s the author’s belief that Robert’s involvement with these films is the reason why many pre-World War II era films by Audio Productions (i.e. Symphony In F) have a very Jam Handy look and style to them.

Who directed and/or animated Symphony In F is a little bit of a mystery as a director’s credit is not included in the film’s credits nor in the trade articles highlighting the film. However from researching Audio Productions the author believes the director and stop motion animator may have been a man named Henry L. Roberts (sometimes credited as H.L. Roberts). Prior to Frank Goldman’s departure from Audio Productions to Jam Handy in 1935, Roberts frequently worked with him on mixed media films that featured stop motion animation. Roberts basically took Goldman’s reigns in 1935/36 and kept his filmmaking style alive at the studio, as can be seen with the 1935 film The Wonder World Of Chemistry (produced for E.I. Du Pont), the Let’s Go America series (produced for the National Industrial Council), and 1937’s Singing Wheels (A Wilding Pictures Production for the Automobile Manufacturers Association that was apparently subcontracted out to Audio Productions). It’s the author’s belief that Robert’s involvement with these films is the reason why many pre-World War II era films by Audio Productions (i.e. Symphony In F) have a very Jam Handy look and style to them.

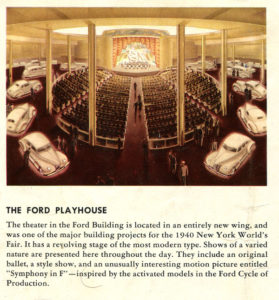

Symphony In F was only shown during the second season of the 1939/40 World’s Fair and played in the Ford Playhouse. The playhouse was not present during the first season and was constructed shortly after it’s end (October 31, 1939) as a gimmick to boost more attendance for the pavilion’s second season; Apparently the Ford pavilion did not exhibit any films during it’s first (1939) season. As indicated by an article in the Volume 2 Number 6 issue of Business Screen Magazine, Symphony In F’s production began following the end of the fair’s first season, and was created with the intentions of not only showcasing The Cycle of Production but also outdoing it’s 1934 predecessor, in Technicolor. To quote part of a letter featured in the article by Audio’s Vice President A.J. Wilson:

“In 1934 Audio produced Rhapsody In Steel for the Ford Motor Company. That picture was extremely successful at the Century of Progress in Chicago in 1934 and we are hoping that Symphony In F will be even better”.

The entire, intriguing article can be read below:

The film was completed in time for the second season of the New York World’s Fair and public showings began around May 11, 1940 when the fair opened; it was not registered for copyright as it’s listing is absent from the copyright catalogs. At the time of it’s release it received positive reception from trade magazines, most notably from Business Screen Magazine who hailed it in a full one page review as “an entirely new type of film production” and reprised technical details from their earlier preview. The 1940 souvenir booklet for the Ford pavilion featured a brief description of the Ford Playhouse and advertised Symphony In F as an “unusually interesting motion picture inspired by the activated models of the cyclorama”. The reviews hint that it may have been enjoyed by fair attendees, which mainly would have consisted of working middle class families and children.

Following it’s exhibition at the World’s Fair, which ended on October 27, 1940, Ford Motor Company made the film available to Ford Dealers for non-theatrical showings at club meetings and schools; Trade reviews indicate that it was not distributed theatrically. Prints used for the post-fair non-theatrical showings featured added narration by Linton Wells to put many of the scenes into context. Strangely, once World War II arrived the non-theatrical screenings seem to fade out, causing it to disappear from the public’s eye for good. An explanation as to why the film came and went, may have dealt with the reality that Symphony In F’s overall reception was extremely mixed and not enjoyed by the public as indicated. One hint of this is in a 1976 biography on Henry Ford written by David Lanier Lewis entitled “The Public Image Of Henry Ford”, in which Lewis notes how Ford executives did not share their company’s positive publicity of the production. The overall attitude amongst Ford executives was that the film was a ‘confused production’ and a ‘puzzling combination of [Disney’s] “Snow White” with an educational, industrial reel’! Sadly this criticism is pretty much shared by the author when comparing the production to Frank Goldman’s Rhapsody In Steel.

In the author’s opinion, While Rhapsody In Steel could be described as an early Disney Mickey Mouse sound cartoon filled with ambition, Symphony In F seems more like a ‘Silly Symphony imitator’ that uses stop motion animation and Technicolor as a gimmick. The use of Technicolor is kind of bland, as it doesn’t experiment with the use of color and also unintentionally removes the atmospheric beauty that was captured in Rhapsody’s black & white cinematography. The use of montages and sequences with superimposing footage, all of which made Rhapsody’s live action sequence a symphonic visual masterpiece, is completely absent in this 1940 update. The stop motion animation sequences to Symphony In F, rely too much on the actions of the Cycle of Production scenes and overall lack the humor and imagination that was brought to the screen by the animated V8 Imp several years earlier. One other detail that also ruins the film is how some of Symphony In F’s animation sequences use humor based around racial stereotypes (commonly used in films and cartoons around this time), unlike Rhapsody In Steel which used absolutely none and depicted everyone proudly working together.

In the author’s opinion, While Rhapsody In Steel could be described as an early Disney Mickey Mouse sound cartoon filled with ambition, Symphony In F seems more like a ‘Silly Symphony imitator’ that uses stop motion animation and Technicolor as a gimmick. The use of Technicolor is kind of bland, as it doesn’t experiment with the use of color and also unintentionally removes the atmospheric beauty that was captured in Rhapsody’s black & white cinematography. The use of montages and sequences with superimposing footage, all of which made Rhapsody’s live action sequence a symphonic visual masterpiece, is completely absent in this 1940 update. The stop motion animation sequences to Symphony In F, rely too much on the actions of the Cycle of Production scenes and overall lack the humor and imagination that was brought to the screen by the animated V8 Imp several years earlier. One other detail that also ruins the film is how some of Symphony In F’s animation sequences use humor based around racial stereotypes (commonly used in films and cartoons around this time), unlike Rhapsody In Steel which used absolutely none and depicted everyone proudly working together.

Now, It’s certainly not the intention of the author to completely trash Symphony In F and whine about how it was not the production it should have been. He doesn’t hate it, as (excluding the politically incorrect scenes) there are some qualities to the production that are enjoyable and worth taking a look at. As a stand alone film it is an interesting piece of American ephemera that offers viewers some rare spectacular Technicolor footage. It does overall document The cycle of Production as it shows all of it’s various scenes and the craftsmanship that went into them, up close. The Technicolor footage of the Ford Factory, along with the shots of the various Ford Cars are interesting and would make for excellent stock footage. From a graphic design standpoint, everything from the opening tiles, use of fonts, to the look of the overall look of the film is nicely composed.

The stop motion animation on a technical level is well polished, beautifully shot, and has it’s charm; The ending parade which utilizes inanimate objects to depict various creatures, while a little odd, is kind of clever. Edwin Ludig’s score, which is really the highlight of the entire film is enjoyable and a nice relaxing piece of music; the author has it in his iTunes library and enjoys listening to it when working on various projects. While it may not be the remake that Frank Goldman would have done (as indicated by the films he was working on for Jam Handy around the same time), it’s still an interesting little piece of history that’s worth viewing for it’s cinematography, stop motion animation, and documentation of the Cycle of Production. Below is a video that features a recent, beautiful HD 1080p transfer of the film’s 35mm elements, the National Archives did. (Hopefully a similar transfer will be done of Rhapsody In Steel)

PS In case your curious what Frank Goldman was involved in around this time at Jam Handy it’s highly recommended you watch “Auto-Lite On Parade” (1940) and “Refreshment Through The Years” (1939) and “Leave It to Roll-Oh” (1940).

SPECIAL THANKS: Acknowledgment is given to the National Archives, The Media History Digital Library, Preligner Library, and to Paul M. Van Dort’s 1939 World’s Fair website for providing access to the information contained in this article.

Next Week: “Nicky Nome Rides Again”! And the week after that, “The V8 Imp Rides Again?”.

EDITORS NOTE: Devon’s Baxter’s column will return on Wednesday’s beginning on August 15th.

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Well, I’ve owned a ’73 F-250, ’80 Pinto MPG, ’84 Thunderbird 5.0, ’86 F-150, ’90 Mark VII, and stuffed a SVO engine into a ’79 porthole Pinto. After all that, I thought that I suffered enough and owned a ’98 Dodge Ram 1500 5.9, a ’85 Buick Riviera, and a ’17 Subaru Impreza…..

“When ‘Murica Wuz Great”? Now I can see why some people have a nostalgic sense of lost glory. And this is from somebody that jonesed for the Googie futures that are never going to come. BTW, did stuff like this influence Disney “Small World” type of stuff.

Probably not this film. The General Motors Motorama may have though… (That was the most popular attraction of the fair.)

I’m thinking would this be at least as much automatia as stop-mo? Most of these thingies seem to be motor driven and going through repeating cycles.

Wouldn’t doubt there’s a few tricks done to get it made like this.