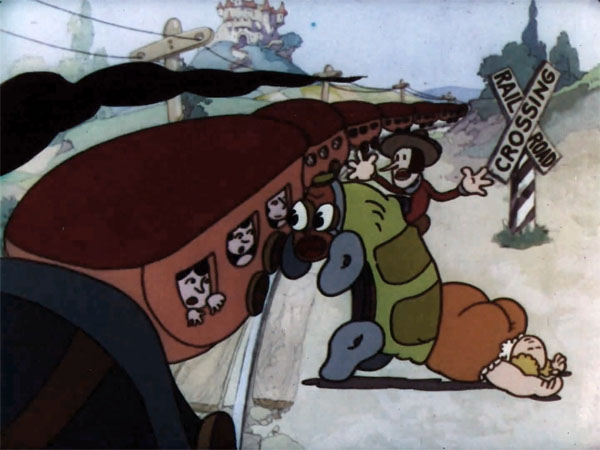

One of many scenes throughout Once Upon A Time in which the crude animation, unintentionally adds humor to the film.

A Special Agreement

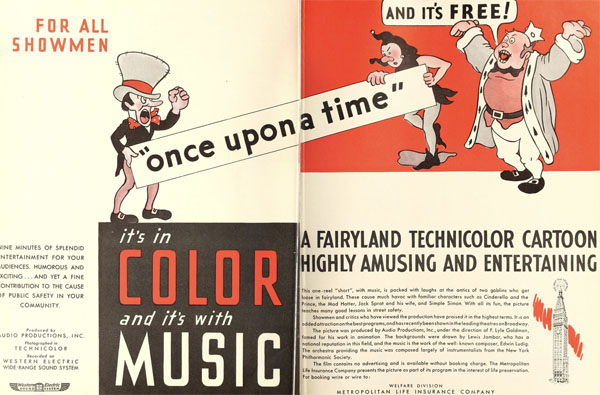

The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and Audio Productions’ Frank Goldman saw extreme importance in using three-strip Technicolor for their safe driving cartoon Once Upon A Time. However at the time the two parties pursued the project, Walt Disney had an exclusive contract to it, preventing other studios from making three-strip Technicolor cartoons. Instead of waiting for Disney’s exclusive contract to expire, Metropolitan and Audio saw an important need for three-strip Technicolor and went out of their way to negotiate a strict, one time use agreement with the Technicolor Corporation that would allow them to make Once Upon A Time and release it theatrically. There are a handful of reasons why Metropolitan would go to great lengths to negotiate a special contract, the most obvious being that Technicolor was the only process that could accurately reproduce green, red, and yellow, the colors affiliated with safe driving (traffic lights, amber stop signs, etc.).

Carelessness’ and Discourtesy’s over-dramatic introduction (enhanced by Edwin E. Ludig’s musical score). As mentioned earlier, Goldman and Metropolitan saw an important need to use Technicolor as an educational aid. Along with accurately depicting the correct colors of road signs and traffic lights, they also used color to help tell the story. Note how Discourtesy is blue and Carelessness is purple, two colors not associated with road signs or driving (during the 1930s), and how they were trapped inside a yellow box, a color that is affiliated with safety.

However and interestingly, at some point between April and October of 1934 (as the cartoon was finished in November/December) Audio Productions, Metropolitan Life Insurance and Technicolor appear to have re-negotiated the agreement so the film could be released both non-theatrically AND theatrically! Today this re-negotiation is currently lost to history thus making the exact restrictions and clauses put on Audio and Metropolitan a mystery. Despite this absence there are a few clues scattered about that hint at what these restrictions were and how negotiations may have been made.

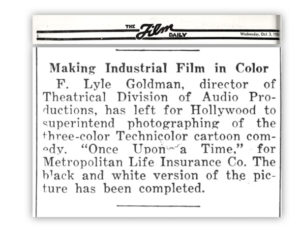

The first set of clues are mentioned in a brief article that was published by Film Daily on October 3 1934:

Note two important details:

Note two important details:

1- Frank Goldman had to travel out to Hollywood from New York City (the location of both Audio Productions and Metropolitan Life Insurance Company) to supervise filming of the cartoon.

2- Mention of a completed black and white version of the film (which appears to have been filmed out in New York City at Audio Productions’ studio.)

To briefly address the first detail, the agreement did require the cartoon to be filmed out in California at Technicolor’s Hollywood headquarters. As indicated by JB Kaufman, Technicolor required that all use of their equipment, filming and processing be done on their property; this even applied to Walt Disney as his early Technicolor Silly Symphony cartoons were filmed at Technicolor’s Hollywood building.

The second and most interesting detail in the article is the mention of a black & white version of the film. As observed from looking at trade ads following the completion and release of Once Upon A Time (in November/December of 1934), the only version released in 1934 and 1935 appears to be the Technicolor version, as there are no mentions of a black & white version.

A 1930s era stop sign as seen in Once Upon A Time. From 1922 to 1954 stop signs were originally standardized as yellow octagons with black text. (In 1954 they were changed to the now used red sign with white text.) In 1934, three-strip Technicolor was the only color process capable of accurately reproducing yellow, unlike the commonly used two-color processes such as two-color Technicolor and Cinecolor.

• How Technicolor would be used in the production.

• That the cartoon was being used to address a serious public issue, and not trying to be a Silly Symphony imitator and cash in on Disney’s fame. (It’s worth noting that several nursery rhyme characters such as Three Little Pigs, the Little Red Hen, The Pied Piper, all of whom had Silly Symphony cartoons made about them prior to 1935, do not appear in Once Upon A Time).

• Further persuade Technicolor to allow the film to be released theatrically and not limited to the non-theatrical field. (Certainly, a viewing of Man Against Microbe was included and it’s success discussed to help further negotiate this.)

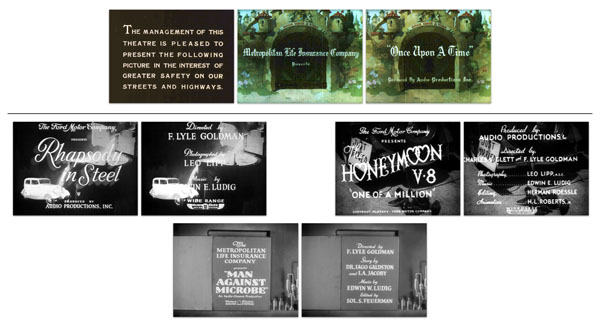

The final set of clues can be found in the actual finished Technicolor cartoon itself, Once Upon A Time, specifically two characteristics that make it unusual for a cartoon, or for an Audio film made in 1934. The first unusual detail is the cartoon’s credits: Compare them to three other Audio films made around the same time: Rhapsody In Steel, The Honeymoon V-8, AND the other Metropolitan Life Insurance Company sponsored production Man Against Microbe.

As seen, there is a dramatic difference in Once Upon A Time’s opening sequence. Missing is:

• Any mention of a copyright date. (It’s worth noting that the film does not appear to have been registered for copyright, as it is absent from the copyright catalogues. Another restriction?),

• A “Wide Range” Western Electric Sound System logo (FYI, Western Electric was owned by A.T.&T., who also owned Audio Productions),

• A directors credit for Frank Goldman,

• An animators credit,

• A musical directors credit for Edwin E. Ludig,

• Any elaborate title art/sequences, best demonstrated in Man Against Microbe and Rhapsody In Steel,

• And a credit for Technicolor.

Instead the screen credits unimaginatively only make reference to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and Audio Productions in simple Old English styled text with no elaborate title art. Interestingly however, the credits were all printed on this large two page trade ad for the film; Notice how they feature everything usually found in the standard Audio screen credits!

So, this is the author’s theory: One of the agreements to have the film released theatrically was that only Metropolitan and Audio would receive screen credits to indicate that the film was not a Disney film, and no one or anything else would receive a screen credit. Imaginably, if Audio Productions was able to give the film it’s usual title treatment, here’s how they probably would have played out (as demonstrated in this video created by the author):

This brings us to the cartoon’s second unusual characteristic: Once Upon A Time’s bizarrely crude animation and off model characters. When comparing Once Upon A Time to other films credited to Frank Goldman (both projects in his Audio and Jam Handy portfolios such as Rhapsody In Steel, Kool Penguins, A Coach For Cinderella) the author feels confident that Once Upon A Time should have been a much better animated film. It’s worth noting too that John Walworth and Hicks Lokey certainly had the skill and talent to create more polished animation, and also Metropolitan and Audio did invest in Louis Jambor to design beautifully ornate backgrounds for the cartoon. So why the sloppiness? There may be an explanation which involves the black & white version briefly mentioned in the October 3rd, 1934 issue of Film Daily.

Note the dramatic difference in the film’s animation and character designs versus the characters in the background. One must seriously wonder (when taking into account the author’s black & white theory), if it was originally the intent of Frank Goldman to upgrade the character models and animation while reanimating the film in Technicolor.

• Technicolor gave Audio/Metropolitan a green light to go ahead with the color production but charged a higher rate to use the process, thus eliminating money that was going to be used to upgrade the animation.

• Technicolor approved the use of Technicolor, only if the film/animation was not altered.

• Technicolor approved of the film with no restrictions on the animation, but John Walworth and/or Hicks Lokey were not available to help reanimate the film.

• There were no restrictions put on the production by Technicolor, but Metropolitan and Audio felt the animation unintentionally contributed to the film’s humor, therefore left it as is.

• There were no restrictions put on the production by Technicolor, but Metropolitan and Audio felt the sloppiness of the animation would further show that the cartoon was not trying to cash in on Walt Disney’s success.

The possibilities as to why this was produced as it was are almost endless. Regardless, Metropolitan and Audio negotiated an agreement with Technicolor and by October of 1934 Frank Goldman was out in Los Angeles filming the cartoon in Technicolor. By December of 1934 Once Upon A Time had been completed and was being distributed theatrically and non-theatrically by the Welfare Division of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. It was made available to theaters and also police departments (to sponsor screenings) across the country without any charge.

Next week in part 3 I’ll explore the impact and forgotten legacy of Once Upon A Time. Below is a little teaser for next week:

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Jonathan A. Boschen is a professional videographer and video editor, who is also a film and theatre historian. His research deals with pre-1970s movie theaters in New England and also film history pertaining to the Jam Handy Organization, Frank Goldman, Ted Eshbaugh, Jerry Fairbanks, and industrial films. (He is a huge fan of industrial animated cartoons!). Currently, Boschen is working on a documentary on the iconic Jam Handy Organization.

Then why did it have to it go past the Hays Office? Some vintage advertising films didn’t need it for theaters, and some did. I am confused….